0. 1/28/2012 – Art Attack Call for Submissions, by Riese

1. 2/1/2012 – Art Attack Gallery: 100 Queer Woman Artists In Your Face, by The Team

2. 2/3/2012 – Judy Chicago, by Lindsay

3. 2/7/2012 – Gran Fury, by Rachel

4. 2/7/2012 – Diane Arbus, by MJ

5. 2/8/2012 – Laurel Nakadate, by Lemon

6. 2/9/2012 – 10 Websites For Looking At Pictures All Day, by Riese

7. 2/10/2012 – LTTR, by Jessica G.

8. 2/13/2012 – Hide/Seek, by Danielle

9. 2/15/2012 – Spotlight: Simone Meltesen, by Laneia

10. 2/15/2012 – Ivana, by Crystal

11. 2/15/2012 – Gluck, by Jennifer Thompson

12. 2/16/2012 – Jean-Michel Basquiat, by Gabrielle

13. 2/20/2012 – Yoko Ono, by Carmen

14. 2/20/2012 – Zanele Muholi, by Jamie

15. 2/20/2012 – The Malaya Project, by Whitney

16. 2/21/2012 – Feminist Fan Tees, by Ani Iti

17. 2/22/2012 – 12 Great Movies About Art, by Riese

18. 2/22/2012 – Kara Walker, by Liz

19. 2/22/2012 – Dese’Rae L. Stage, by Laneia

20. 2/22/2012 – Maya Deren, by Celia David

21. 2/22/2012 – Spotlight: Bex Freund, by Rachel

22. 2/24/2012 – All the Cunning Stunts, by Krista Burton

23. 2/26/2012 – An Introductory Guide to Comics for Ladygays, by Ash

24. 2/27/2012 – Jenny Holzer, by Kolleen

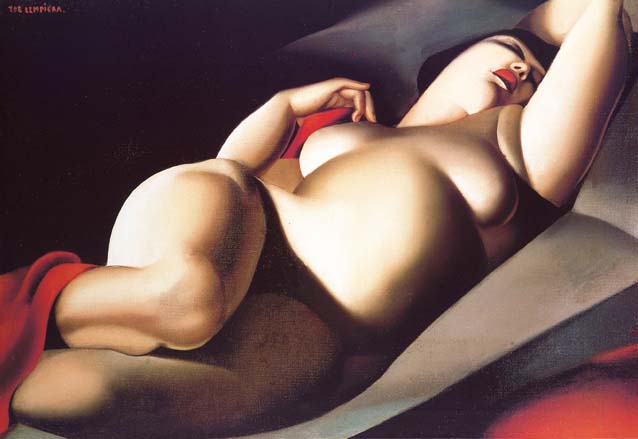

25. 2/27/2012 – Tamara de Lempicka, by Amanda Catharine

![]()

Some art below could be NSFW, so scroll with caution.

“Have you heard of Tamara de Lempicka? She was Art Deco, but didn’t do posters. Or maybe she did like, one. Have you heard of her?” E asked. E sat next to me in my first art history course, and she was obsessed with the 1920s. I hadn’t heard of Tamara de Lempicka, as it happened, but by the end of class I’d spent more time googling images with E than I had listening to the professor’s introduction. E was passionate about de Lempicka because she was an artist herself, and loved de Lempicka’s use of color. I would come to appreciate de Lempicka’s work as well, but would also wind up fascinated by her life. After all, how could you not be intrigued by a woman who proudly proclaimed, “I live life in the margins of society, and the rules of normal society don’t apply to those who live on the fringe”?

Tamara de Lempicka is something of a controversial figure in the art world. One of the paintings below, “Rafaela sur fond vert,” was featured in a fairly recent New York Times article about its sale, saying that the painting was “done in the artist’s best — some would say worst — hyper-realist style…” I would argue that she’s frequently overlooked in general historical surveys of Art Deco, even though her work continues to be well-known and well-liked. Biographies abound, because she lived a glittering life, and retrospectives are always accompanied by lavishly illustrated books with insightful critical essays, but in my experience, she’s not really taught in art history courses. She’s basically a footnote, if she’s mentioned at all, in the major textbooks. Her work is featured in permanent collections of museums and galleries worldwide, and in several of Madonna’s music videos, yet art historians don’t pay her much attention.

Perhaps that popularity is part of the problem. Tamara de Lempicka was a trained artist who created compelling, original, arresting works that are virtually immediately recognizable. She proves difficult to classify: traditionally called an Art Deco artist, she learned much from Cubism and challenged the limitations imposed on the life and art of a woman. She escaped war-torn Russia penniless, moved to France and rebuilt her fortune with her brush, raised a daughter, slept with her models and didn’t care who knew, threw fabulous parties, married into an enormous fortune and a title, and escaped World War II Paris for sunny California, before moving to Mexico where she lived out her final years. In a word, Tamara de Lempicka was pretty brassy, particularly for a lady who was born in 1898.

As a daughter of the aristocracy, de Lempicka had a taste for the high life, and painting was her way of making money. Did she compromise herself artistically in order to earn more francs? Perhaps. Might we have had the works that we do find so compelling today if she hadn’t managed to secure lucrative patronages? Maybe. Art historians are complicit in perpetuating the idea of the tortured artist, starving in an attic in Paris, getting by on the generosity of friends to buy materials to create Art. It’s a seductive image, and there’s more than a little truth to it, but it’s ultimately a misleading paradigm if it is the only valid lifestyle for producing art: there are lots of artists who make interesting things, and are also willing – eager, even – to work for money as well as aesthetic satisfaction. Commissions pay the bills so artists can create Art. Even Leonardo painted portraits of his patrons’ wives. But I think it would be fair to say that there is less latitude and acceptance of an artist who sought out wealthy supporters when the artist in question is a) not Leonardo and b) a woman who goes on to marry one of her wealthiest patrons.

autoportrait (1925)

I love her work. Too often, I think she’s reduced to biography when she does merit sincere critique. I really like her manipulation of space within the work, particularly in works like this one, “Autoportrait,” created as a cover illustration for the German magazine Die Dame in 1925.

Forcing the subject so far into the foreground allows de Lempicka to emphasize the power of her Bugatti, to make the car (the “auto” of her play-on-words title; in French, “autoportrait” means “self-portrait”) just as important a figure as her self-portrait. The work is also significant for its rendering of a woman, by a woman, as a contemporary, independent figure who’s not only challenging the male gaze, but asserting herself and pushing forward. Only her eyes look out at the viewer; her face itself is oriented straight ahead. This is a woman unafraid to blaze her own trail.

“Unafraid” is certainly a good word to describe Tamara de Lempicka, who was a thoroughly modern woman eager to manage her own affairs. Her love affairs were plentiful, and she counted wealthy, titled patrons (one of whom, Baron Raoul Kuffner, would become her second husband), models, and friends among her lovers. Her romances were frequently public, given that they were often carried on with the well-known figures, male and female, who also frequently sat for her paintings.

la belle rafaela (1927)

Rafaela sur fond vert (1927)

The model Rafaela, who sat for “La Belle Rafaela” (1927), has been rumored to have been one of those models-turned-lovers. De Lempicka revisited Rafaela in varying poses in several works, although little is known about Rafaela herself. “Rafaela sur fond vert” (1927) shares some similarities with the famous odalisque in “La Belle Rafaela” that are hallmarks of de Lempicka, like her attention to modeling, strong lines, and a fantastic sense of shadow and light, all rendered with an eye toward a modernizing, Cubist-inspired distortion that lifts her work out of realistic depictions and into a readily recognizable, stylized form.

What I love about looking at these two works side-by-side is being able to see two such different sides of Rafaela. In “Rafaela sur fond vert” Rafaela covers her breasts almost demurely, yet meets the eye of the viewer with a steady, heavy-lidded gaze. “La Belle Rafaela” is more overtly sexual, and yet here she is more vulnerable, displaying her body and hiding her face. It’s tempting to view them both as de Lempicka’s effort to capture her lover in two such intimate poses, but impossible to verify for certain. It’s precisely this tension, however — the tension between subject and painter, subject and viewer, between Rafaela’s powerful figures and the canvases that barely constrain her — that I find so fascinating about de Lempicka. I love that her poses recall classical tropes but reinvent them in a sleek, modern composition.

For further reading about Tamara de Lempicka, look for Laura Claridge’s 2000 biography, Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence. De Lempicka’s daughter Kizette de Lempicka-Foxhall wrote about her mother as well, in Passion by Design: The Art and Times of Tamara de Lempicka.

Feature image: Dormeuse (1932)

Mmm, Art Deco! Great article, I didn’t know about her :D

Art Deco. Diego Rivera like. I think Im in love.

I thought this art looked familiar and then I realized that a book just came out about this artist…kind of. It’s called The Last Nude by Ellis Avery, and it’s a fictionalized account of Rafaela’s affair with Tamara. It looks super interesting and now I want to read it even more!

You know, now that I thin about it, I don’t remember how I heard of Tamara de Lempicka… but I was immediately in LOVE with her portraits and I spent like a whole afternoon just looking at them. I LOOOVED all of them! I loved “La Dormeuse” so much that I tried to imitate it on a self-portrait… I guess it didn’t go so well… =P

http://www.flickr.com/photos/iamilk/4352045657/

i just wanted to say i like this post/this whole art attack month business

I love her painting from the 20s-30s… her later stuff from the 40s-50s, not so much. Another queer woman artist from that period, Gerda Wegener, has similar work (and even racier). But I think Tamara’s claim about living on the fringes of society was more her fantasy than reality (except when she first arrived in Paris and was genuinely broke). She was quite the snob and almost exclusively hung out with wealthy people. Maybe she meant hanging with “naughty” types who were part of the upper crust who, by virtue of their privilege, were able to live beyond societal norms?

Wonderful art.

But what I love best about Tamara de Lempicka is that she and I appear to share the same taste in women.

Rafaela = HOT! DAMN!

when I was about 14/15 I would lurk around a tiny art gallery near my bus station and look at a certain lempicka replica. I bonded with the gallery’s boss over this painting. said boss was the first lesbian my gaydar, at the tender age of 13, detected. late she let me work at the gallery for a short time because she had seen me at gay parties. she didn’t pay me, but gave me this painting for free:

I am just finishing up the fictional work about her life, “The Last Nude.”

de Lapicka’s affair with her model Rafeala is the first part of this book, told first person by the model.

There is a certain ‘Great Gasby’ taste to this book, very wealthy people living out their lives in style and picking at each other for amusement, trying to out do their rivals, all set against 1927 Paris. A lot of famous gays appear in this book, not as cameo’s, but as people engaging with each other.

Rafeala is a seventeen year old who escapes being sent Italy from New York for an arranged marriage and who lands in Paris and survives more through luck than anything else.

Fantastic depth of character and tons of characters in this novel. Very erotic, with a subtle swirl of depravity to it, and a very good taste of what the Twenties in Paris might have been like.

Five stars.

Pingback: Elegy: Jacques Derrida on Sarah Kofman « The Ellipses Project

Good article, although, I if I didn’t know better I would assume that she was Russian (“She escaped war-torn Russia penniless”) when in fact, she was Polish. Born and raised in Warsaw, Poland up until she was 14yrs old. Sidenote: just like Marie Curie, the famous chemist, Nobel prize winner, was in fact, Marie Curie-Skłodowska, (also Polish) which, hardly anyone nowadays knows about, perhaps because, the second part of her surname was too difficult to pronounce. Yet still, this does not justify the misleading historical inadequacies which, so often emerge from such shortcuts.

Pingback: Invicta's Star Wars Watch Collection Gives Geek Chic a High-End Makeover - W Contest