Hello! Welcome to BOOK CLUB DAY! By now you’ve all completed, I hope, The Miseducation of Cameron Post. Maybe you cried in line at the grocery store with one hand gripping your kindle and maybe you cried in your bed on a Saturday morning and maybe you didn’t cry at all while reading it but maybe you laughed a few times, or maybe both. Definitely if you read the same book I read, you closed it wishing it wasn’t over. You closed it wishing for a sequel or even more of the same.

I think the experiences in Cameron Post are familiar to so many queer women — the rural isolation from lesbian culture, the crush on the straight best friend, the religious relatives with prehistoric ideas about homosexuality — and already so many of you have told me how much you relate to Cameron and how her story connects with yours. That’s how I felt reading the book too, except backwards — it was you I thought of when I read this book, not me. If I was in this book, I wouldn’t be Cameron, I’d be Lindsey Lloyd (although that would’ve required substantially more confidence and self-awareness than I actually possessed as a teenager). I can relate to the tragic and sudden death of a parent, but outside of that I was looking at Cameron from the outside, maybe somewhere near where Lindsey or Margot were looking from.

I fell in love with Cameron and with this book pretty early on, just as I would’ve if I’d known her in real life. Because she has so many feelings and she’s trying so hard to figure everything out and isn’t afraid to dig and dig and dig until she gets it. I think that’s part of what makes queer women so awesome, eventually, is that we’re forced by design to develop a really strong relationship with ourselves. We’ve never just “fit right in,” and that experience of being slightly apart makes a person really develop into a brilliant, complicated thing.

So it is with great lovely excitement that I present to you this fantastic and totally epic Cameron Post Post, which contains answers to your questions. Everybody who sent a question for Emily was entered in our drawing to win a Lindsey Lloyd care package and on the last page of this Q&A we’ll tell you who got drawn via Carrie’s Magical Random Number Generator.

Emily Danforth answered 38 questions for you, so I recommend getting some tea, coffee or whiskey, maybe sitting on your couch, sharpening your fingertips, wiping off your eyeballs, and sitting down to read one of my favorite things we’ve ever put together for you here on this website. There’s lots to talk about, and we hope that you will — Emily’s got some questions for you in here and I have a lot in my head, like “what was your favorite part?” and “who broke your heart the most?” but those aren’t as interesting and complicated as what we’re about to get into.

So, without further ado, Emily pontificates on the coming-of-age-novel, the writing process, the book acceptance and publication process, word processing programs, queer politics in literature, lesbian pop culture, Dorothy Allison, Taco John’s… and the possibility of another book that picks up somewhere after Cameron Post left off. (!!!!!) Basically it’s the best treatment ever to Novel Withdrawal.

I loved the balance of the authenticity of the dialog and interaction between the protagonist and her peers, and the heady, often heart-wrenching introspection from Cameron. How did you approach writing for an adolescent narrator without coming off as precocious?

Thanks very much for saying so, glad that all worked for you. For me it comes down to understanding how characterization works, in-scene, and then complementing/complicating that with strategic usage of POV in the passages of narration. Cam as storyteller is a bit older, and a bit wiser, a person, one with a more developed sense of perspective on the things she’s telling you about, than is Cam as character in scene, and I was always trying to remind myself of that and use it as a potential place for tension-building in the novel.

I see Cam, the person telling you, the reader, this story, as maybe a twenty or twenty-one year old, so she’s put some of this behind her, or worked it out, I suppose, in order to be able to now tell the story to you. But, I think her narration also reveals some of the ways in which she hasn’t yet processed all of these experiences as fully as she might pretend to, and, in fact, telling the story is helping her to do some of this processing. This is her “reflective distance” from her own past, and utilizing that distance, that slightly older, introspective voice, throughout the novel, was all pretty strategic.

“Sometimes when people ask me why I write, I tell them that it’s because I grew up gay (very gay) way out in the middle of cowboy country in the windswept and dusty badlands of eastern Montana.”

However, sometimes I had to mute that reflective voice when Cam was remembering a specific moment that would become a scene in the novel—or at least turn the volume way down on it—to better help you, as a reader, just be there in those moments with her. It’s a tricky negotiation and it doesn’t work the same for every scene in the book. Sometimes she’s doing quite a lot of narrative “interpreting” as she’s showing you this scene, other times she’s just painting the picture for you. Mostly it’s just honoring your characters, in this case, my main character, and trying to present her as wholly as possible, not to pander to a certain ideal of type, or to use her as a puppet serving my plot, but to attempt to honor Cam’s humanity on the page. That sounds sort of silly, maybe, but it’s as accurate a piece of my process as I can explain it.

Where do you live now? How do your Montana roots impact your queer identity?

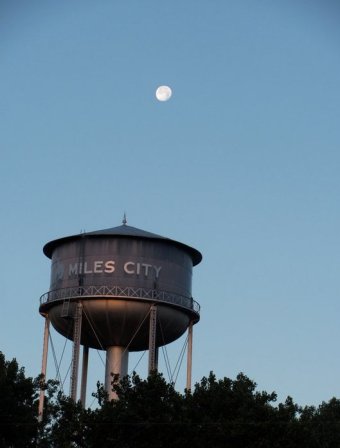

I live in Providence, Rhode Island—a city I love. We’ve only been here for a year and a half but both my wife and I are completely in love with Providence. It’s such a great, small, coastal city. I’ve always been really drawn to New England, for whatever reason (too many John Updike/John Irving novels…) and if we don’t live here forever, for always, it will likely still be somewhere coastal (the Pacific Northwest is very nice, too.) But, despite that, I think I’ll always consider myself a Montanan. All of my most formative years were spent there, and the whole of my immediate family still lives there—which means I’m back in MT at least once a year, often more than that. And I long for it, I do, when I’m away for too long—that landscapes works itself into your very being, I’m telling you, it haunts you until you return and get your fix. I wrote a little about this awhile ago, at least how growing up in Miles City affected me as a queer writer. Here’s how I put it then:

Sometimes when people ask me why I write, I tell them that it’s because I grew up gay (very gay) way out in the middle of cowboy country in the windswept and dusty badlands of eastern Montana. I don’t know that this answer is very satisfying to anyone. Sometimes people chuckle, uncertain. Sometimes they cock their heads, ask me to elaborate. Sometimes they just nod knowingly (you know how some people do that). What I think I mean by that answer, though, is that falling in love and in crush with other girls in Miles City, Mont. in the 1990s felt so fraught and, frankly, dangerous that from the ages of 8 to 18, closeted-me inhabited a very active and wholly imagined fantasy world in which a braver, not-closeted-me, was, well, braver and not closeted. All this time spent imagining other worlds, and other versions of me in those worlds, was eventually good fuel for fiction writing. But more than that, growing up this way — which is to say, growing up in the closet — kept me on the periphery of so many of the crucial rites of American adolescent passage: first dates and kisses and dances, those formative individual events, most of them small, to be sure, but you add them all up and there’s real weight there for those of us who missed out on all of them.

So, you know, there you go. All of that experience was formative for me, as a writer, as a queer, as a queer writer.

emily danforth

How much of the book was based on research? Could you talk about any research that you did? What, if anything, was the book based on and what inspired it?

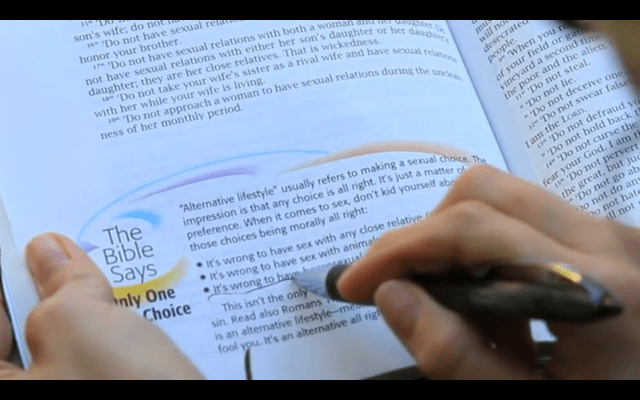

How did you go about researching the “conversion” school Cameron is sent to?

Much of the “treatment” focused on in the God’s Promise section comes from actual research I did. That research took many shapes and forms. I read all kinds of books from various practitioners of these therapies (and ordered materials directly from Exodus International, an organization that’s really changed its rhetoric in recent months, but that remains in its function as a referral network for many ex-gay ministries—despite that even they have now mostly parted ways with that term); I also spent hours and hours combing the websites and blogs of these ministries and practitioners, and also folks who themselves claim to be “ex-gay” or who have just spent time on the receiving end of conversion/reparative therapy, (And I had one on one conversations with many of these people, in chat-rooms or via email.)

I even got access to the offical application materials and “residence manual” for a live-in reparative facility for adults in Kansas. (The dorm manual in the middle of the novel is based on those materials.) I watched several documentaries on the topic, too, including the excellent One Nation Under God (1993—directed by Teodoro Maniaci, Francine Rzeznik and not to be confused with the 2009 film of the same name, also a documentary.) It was a particularly useful film, not only because it’s a documentary, but because it’s from roughly the same time period as the novel. Exodus International was just Exodus back then, or Exodus Ministries (no International component), and it has changed significantly, as well, between the time period covered in the novel and today, so only using recent resources just didn’t make sense given that Cam’s world is one from twenty years ago.

However, the facility itself, as built in the novel—God’s Promise–is an invention, it’s fiction—there is not specific school or facility that it’s based on. The practices that happen there, yes, but the place is my own, one born of my research.

As for inspiration, shoot, that’s impossible to answer, really. It’s inspired by so, so many things, from novels I’d read to music I love (or once loved) to films, my own memories, the landscape of Montana, growing up in the closet, being horrified by conversion therapy and its practitioners. I can’t pin any of that down to one satisfying answer. It was my first novel and it had been bubbling away inside me for a very long time, its points of inspiration are many.

Did you have someone like Lindsey Lloyd in your formative years? Or have you been that person to someone?

I didn’t have a Lindsey Lloyd type figure in my life until college, sad to say, and by then I was old enough, had experienced enough, that she didn’t have quite the same effect on me as she did on Cam—or as she would have on me had I met her at 12 or 13, or even 14 or 15. But, still—there were a couple of friends who I met early on in college who introduced me to some aspects of dyke culture that I was unfamiliar with, absolutely. My best “fairy gay,” though, was/is my friend Ben. We also met in college. I was already out and he’s no lesbian, but we did proclaim ourselves the school’s “favorite gays,” and then worked really hard to live up to that self-bestowed title, mostly by throwing lots of parties. If it sounds like gross behavior it might have been, I’m afraid, but we simply did not care. (Mostly because we were drunk.)

I would have LOVED to have had a Lindsey Lloyd in my life in high school, despite some of her (delightful) flaws. A Lindsey in high school would have saved me some heartache, I’m sure. I don’t know that I’ve specifically been a lesbian fairy godmother to anyone, the “keeper of the light of dyke knowledge,” I mean, but I did spend a chunk of my early twenties as a kind of Lindsey Lloyd. I see a lot of my 19, 20, 21 year-old self in that character. That’s not an entirely good thing, maybe, but it’s true.

As a queer writer, do you consider your work necessarily political? Would you ever write a book that didn’t focus on queer issues, or do you feel as though part of your mission/responsibility/identity as a writer is wrapped up in being queer?

Certainly I’m used to my sexuality as being understood, by many, as political—that’s just part of any out queer’s current experience. (It’s not, frankly, fundamentally understood by me that way, but I live in a culture and at a time wherein any non- heteronormative desire or embodiment is necessarily political. The very recent election and the great successes for marriage equality (and queer representation in congress) indicate a real kind of progress in terms of shifting political views, nationally, on issues that pertain to lesbians and gays, but it’s also one that’s easy to problematize given all that’s bound up, politically, in the institution of marriage, no matter the gender of those getting married—but it’s social progress nonetheless and I appreciate it as such.)

All of this is to say that heteronormativity makes any exploration of queer desire in a work of fiction political for some readers, while at the same time some explorations/representations feel not nearly political or politicized enough for other readers (often, unsurprisingly, queer readers.) One of the things I’m most interested in exploring when I write fiction is desire—romantic, sexual, even aesthetic. Desire is so often messy and complicated, even fraught—it’s good material for fiction. And what I know best is queer desire, so I’ll always, always be writing about that. Guaranteed.

I wanted it to be a great big coming of GAYge novel, one that both represented the literary traditions/tropes of the American coming-of-age novel and also one that queered some of those traditions, or answered back to them, subverted them.

I wanted Miseducation to be a great big coming-of-GAYge novel, one that both represented the literary traditions/tropes of the American coming-of-age novel/novel of development, and also one that queered some of those traditions, or answered back to them, subverted them. As such, it necessarily explores the formation of queer identity(ies) in a fairly microscopic and chronologic way. I’ve now written this novel, though, and I’ll never write it again. (Unless, I suppose, I ever write Cam’s continuing adventures, which would be its own novel, but would tread in similar territory.) What I mean is: I won’t again write a novel that’s structured as a coming-of-age novel, a novel that explores queerness in quite this way. It’s always been important to me that each successive novel I write take a new approach in terms of structure, in terms of construction (and of course in terms of plot and content), though undoubtedly some themes I’ll return to again and again. However, I’m writer that deals in specifics.

audre lorde

Like Dorothy Allison, I want my fiction to “break down small categories,” to feel authentic and powerful in the specificity of its rendering. Allison also said “some things must be felt to be understood, that despair, for example, can never be adequately analyzed; it must be lived…”

She’s talking, of course, about the power of literature to transport readers not only to different times and places, but to different selves, to emotional landscapes that cannot be effectively discussed in, say, academic speak—and that’s a power that I seek to utilize in my own fiction. Audre Lorde famously wrote, “There’s always someone asking you to underline one piece of yourself – whether it’s Black, woman, mother, dyke, teacher, etc. – because that’s the piece that they need to key in to. They want to dismiss everything else.” I believe that one of the powerful things character-driven fiction can do is offer narratives that refuse those kinds of dismissals, that kind of essentialism.

In the novel, many characters are presented sympathetically and multi-dimensionally, including those who are using religion as an excuse for intolerance. Was it difficult to create those characters who were prejudiced?

This was something that was pretty crucial to me as I wrote—getting these characters to feel multidimensional on the page. Aunt Ruth, for instance, was a character who went through substantial revision as the drafts piled up, and I’m still not sure she’s as complicated/compelling as I’d ultimately like for her to be. I absolutely did not want the evangelical Christian characters in this novel—even those running God’s Promise—to be merely zealot-puppets that I could manipulate in scene to reveal my own views and agenda.

However, some readers of early drafts called me out for writing caricatures and not characters, and I think those criticisms were pretty fair. No surprise that it’s challenging to authentically and fairly treat characters (on the page) who espouse viewpoints and live ideologies that you so vehemently disagree with. I revised several scenes because I kept making those characters, in my novel, too one- dimensional and cartoonish. (The problem being that it’s hard for me not to experience most zealots, in life, as cartoons, even as I see them in front of me on TV or on the street—my way of looking at and experiencing the world is just so removed from any of that—so it was a personal challenge to try and move beyond that kind of portrayal in my novel.)

screenshot via “the miseducation of cameron post” trailer

How did you develop your prose style? Were there any writers who were particularly influential of your style?

I developed it by reading a whole lot and writing a whole lot, and, importantly, thinking pretty critically about craft, but then also purposefully not thinking much about it, frankly, when I sit down to do early drafting. I can think more strategically about technique when I’m revising, but in its early stages my fiction doesn’t come from craft, it comes from ideas or memories, from small moments of this or that—the nostalgic potential of a particular smell, a bit of conversation I’ve overheard, some grievance or terror or piece of a tragedy—that I want to “get at” in fiction. I studied fiction, as a craft, in a couple of graduate programs and unquestionably all of that careful attention paid to fiction—and the workshopping process—helped me to refine my style. (Though if I look at pieces of my writing from my late teens, early twenties, that style—some of my preferred usages of technique, that is, my stylistic tics, are already emerging.)

There are many, many writers who have influenced me, though I don’t know that it would be correct to say that they’ve influenced my style, in specific. In particular I’m drawn to Steinbeck’s ability to render place; to Sarah Waters’ colorful treatment of history and her always delicious plots; to Nabakov’s sentences; to Roald Dahl’s wit and villains; to Flannery O’Connor’s southern Gothicism and penchant for (grotesque) violence—particularly in her short fiction.

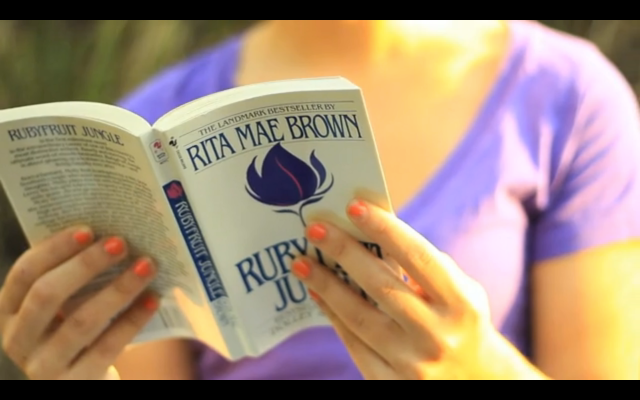

Before writing Miseducation… I really steeped myself in (mostly late-twentieth century) coming-of-age novels, and Janet Fitch’s White Oleander; Wally Lamb’s She’s Come Undone; Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex; and Curtis Sittenfeld’s Prep were all equally influential. (As were books from much earlier in the century, or even before, including Catcher in the Rye, Rubyfruit Jungle, and Susan Warner’s sentimental “classic” novel of instruction, The Wide, Wide World.) If I could pick one novel, though, that I wish I’d written, that I wish I could claim, it would absolutely be Michael Cunnigham’s The Hours. I think it’s pretty much a perfect novel.

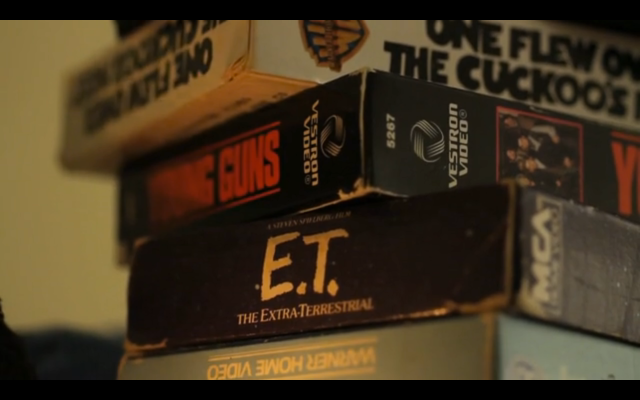

If Cameron was losing it for Coley in 2012, what movie-of-seduction would she bring to the apartment that fateful afternoon? Still The Hunger, or has the cinema of the last twenty years made a new offering?

“the hunger”

Ha!–fun question. Unquestionably there are now more (and better) films with some sort of Sapphic bent for Cam to choose from than there were in 1991. And TV shows and webisodes too, for that matter. It’s all a question of perspective and intent, I think. The Hunger works well for Cam in her particular situation because she has it on hand, for one, and saves time skipping a stop at the video store before heading to Coley’s, but also because while of course she knows there’s going to be some ladies making out in it, she can present it to Coley as just a “wacky vampire story.” And then she gets to enjoy the moments in between, once she’s pressed play, while Coley figures out the other layer to this film—the one that Cam hasn’t mentioned. (Also, it was historically appropriate for my needs as a novelist.)

All of this would necessarily play out quite differently today, given how much more visible (and accessible) are various kinds of LGBTQ representations in our current popular culture—as problematic as some of those representations might be for some of us. I belabor this because Cam’s choice is in some ways made easier—there’s more material to choose from—and also more difficult, for that very same reason. Would she want to pick something that she still thinks Coley wouldn’t be familiar with? So maybe an indie movie? And does she go for a true romance between women, or is just a sex scene between women enough? I mean, if she wanted to hit the nail squarely on the head then it’s, what, an episode of The L Word? (Or now The Real L Word.) That just seems too on the nose to me. She’d probably go for something wherein a seemingly straight woman falls for another woman, but also something that doesn’t feel too complicated or demanding of its viewers, and features youngish protagonists. Maybe D.E.B.S. or Kissing Jessica Stein (but skipping the awful last five minutes of that film, just ending it early, when they’re a happy, functioning couple dancing around to music) or Saving Face. But I’m a Cheerleader or Imagine Me and You might work, too.

Or Bound. When in doubt there’s always Bound, right? It might be perfect for Cam’s intentions, actually, because there’s this complicated crime plot to latch on to, so she could easily present it to Coley “just” as a mob film. Or she could always cherry pick a couple of the Willow/Tara episodes of Buffy. Or just pull up one of the 900 clip reels of lesbian moments in film on youtube (though where’s the fun in that?) One of my very, very favorite films exploring young, fraught, imperfect romance between teenage girls is Lukas Moodysson’s quiet Swedish film Fucking Åmål (which was released in the states as Show Me Love.) That might, in fact, be the absolute perfect choice (though they’d have to contend with the subtitles, which could make following the narrative tricky if they’re simultaneously trying to make out. I’m sure Coley and Cam could figure it out, though.)

So, final answer: Fucking Åmål. If you haven’t seen it you should, it’s incredibly tenderhearted and touching and honest.

Fucking Åmål

This is somewhat embarrassing to admit (and I’m sure you weren’t expecting this follow up when you asked the question), but on one of my very first official dates with the woman who would become my wife—I say official because we’d been friends who had not dated for several years prior—we watched “The Puppy Episode” of Ellen. Anyway, get this, a friend of mine had taped this episode for us—off of the Lifetime network, of all places—because I didn’t have a TV (let alone a VCR) in my dorm room. I was a closeted high school kid when the series was on the air, and so had not tuned in, nor had my wife (though I’d seen “The Puppy Episode” by the time we watched it together on this date), but this very good friend made me two VHS tapes of the final two seasons as a kind of “welcome to your gay life” present, I guess. I still have those tapes, actually. (Despite that I have no longer have a VCR on which to play them.) Anyway, I love the image of the two of us on our first date, sitting on this twin mattress in somebody’s dorm room watching Ellen come out: it’s such a cliché. You’d think we’d have headed to an Indigo Girls concert immediately afterward. (We did not.) I don’t think, however, that I intended it as a potential tool of seduction. I just thought it was funny and that we’d like it (and we did.) I think we might have held hands while watching it. That’s how sweet we once were.

NEXT: On Religion-by-VHS, writing software, the autobiographical elements of the book, Coley Taylor’s sexuality and more!

+

I related to the sentiment of the VHS rentals being Cameron’s “religion of choice.” Which movies held importance and meaning for you personally; are any of them shared with the movies mentioned in the book?

How did you choose which movies to reference throughout the book?

Oh I was absolutely brought up on a very steady diet of crappy VHS rentals (and whatever was playing on HBO—well, what I could catch when my parents weren’t home, which was a lot, actually, given my latchkey kid status.) If we’re talking queer movies, or movies with some lesbian expression or another, then certainly Personal Best was an important one to me fairly early on, so I share that with Cam. Even more important to me personally was Fried Green Tomatoes. That was easy to queer, long before I knew that I was “doing that,” (or before I would have called it that, I suppose). I was completely in love with Mary-Louise Parker as Ruth, and I identified with Mary Stuart Masterson as Idgie. The film isn’t as open/obvious in its treatment of this romantic relationship between the two of them as is Flagg’s novel, but it is readable in some scenes.

There’s a scene wherein Ruth is supposedly teaching Idgie how to cook, and they end up in an all out food fight. It’s hot in this restaurant kitchen—it’s summer in the south and it’s sweaty and they’re cooking with all these sensual foods like ripe berries. It’s incredibly sexual, this scene, while not being specifically a sex scene, it absolutely is (in fact, I think the film’s director—John Avnet–even referred to it as such—that they storyboarded it that way when filming) and I remember blushing the first time I saw it [at age 11], and not quite being able to figure out what was going on or to put a name to it. It’s a food fight, after all, but I knew that there was much more there. For me, they were this ideal lesbian couple even though they’re certainly not presented that way on the screen—at least not specifically, anyway.

Once I was a bit older and started studying film, movies like The Children’s Hour and Mädchen in Uniform (the 1931, original, version) became important to me as early, if problematic, celluloid representation of lesbian desire. But, you know, as child, as an adolescent, I was really able to queer just about anything that I was watching. I did it instinctively, and it wasn’t something that I discussed with anyone until much later.

What kind of writing software do you use – something like Scrivener, or just a normal word editor? Is there anything you would recommend, or recommend avoiding?

I typically just use Word for Mac (I am fully invested in the cult of apple). Word is what I’ve been writing on for more than a decade, now—it’s how I’ve written all of my fiction. It’s basically the equivalent of a nonentity for me, it’s just the slate that’s in front of me that I’m comfortable with, that I don’t have to think about at all to utilize—and I like that. I don’t want to have to think about software when I’m composing. (And, of course, everyone uses it, so sending it to editors or other readers in that form is made very easy.) I did just download Scrivener, actually, and so we’ll see if I end up making use of it for this new novel or not. (Right now the draft is all still in Word.) But I haven’t done more than goof around with it and do the tutorial, so I can’t speak to it in terms of my own writing, though I have a lot of friends who are devoted users.

I have lots of notebooks, too, with little, well, notes to myself about the novel—and I often tack note cards or slips of paper up above my desk with various plot points or character trajectories or just small things that I want to remember and have at hand while writing. These “scraps” are pretty essential to me. I know that Scrivener allows one to house and rearrange and fiddle with all of this kind of stuff electronically, but part of me thinks I might just end up needing the more tactile form.

When it comes to things like software and routines for writing, my recommendation is to do what works for you. It doesn’t matter if Scrivener is the ideal program for another writer—if all its very cool bells and whistles—and they are cool—do nothing for you, then who cares, right? And if your favorite writer says s/he writes for three hours first thing every morning, so you make yourself do that for a few weeks and it produces little for you, or it feels like it suffocates your personal habit of only writing every few weeks, but then, when you do, writing for whole weekends at a go, being completely consumed by it—then drop the other method and use your own. Another writer’s methods are only as good as their usefulness to your own process and goals. (Though I, too, always love to hear about their little rituals, even try some of them out. For me it’s swimming—lap swimming in specific. My writing day always goes better if there’s a lap swim in there somewhere. It’s time I use to process and reflect and work shit out about my characters and often the plot.)

How much of the book is autobiographical, if any? I know that you grew up in the same city as Cameron, but does the connection between you and the character go beyond that?

I read in your bio that you were born and raised in Miles City, just like Cameron Post. How much of the novel is autobiographical, if any?

After reading this book, I would love to know the inspiration for Cameron. Is she based on you? What brought you to her? How do you see her story ending?

How similar are you to Cameron? Are you a movie buff?

I’m going to try to speak to all of the above questions, in some capacity, in this answer. (Wish me luck!) My connections to Cam absolutely go beyond the fact that we both were born and raised in Miles City (or Shitty—as all of you now know), Montana. Some of the connections between our lives are really very specific—locations from my past, certain events and even moments—I absolutely mined my memories of some of my fears and conflicted emotions growing up gay and closeted at that time and in that place. But, in lots of crucial ways, Cam is pure fiction, too. Not surprisingly, I’m asked this question quite a lot, so here’s an answer that I gave to it not so long ago:

I’m going to try to speak to all of the above questions, in some capacity, in this answer. (Wish me luck!) My connections to Cam absolutely go beyond the fact that we both were born and raised in Miles City (or Shitty—as all of you now know), Montana. Some of the connections between our lives are really very specific—locations from my past, certain events and even moments—I absolutely mined my memories of some of my fears and conflicted emotions growing up gay and closeted at that time and in that place. But, in lots of crucial ways, Cam is pure fiction, too. Not surprisingly, I’m asked this question quite a lot, so here’s an answer that I gave to it not so long ago:

Cameron is decidedly not me. She’s a fictional character. She’s not even really a fictionalized version of me—it’s much more specific a process than that. A better way to think of her is as a character built from pieces of my experience growing up gay in Eastern Montana in the early 1990s. However, Jamie (her good—male—friend in the novel) is also a character built from some of my own experiences, and so is Lindsey (her activist in-training friend from Seattle), and so are many other characters in the book, actually. What Cam and I have most in common is that we were girls who liked girls at a time and in a place where that was not sanctioned or even talked about. (And we’re both swimmers. And we both “fell in crush” a lot—though Cam is braver about all of that than I was.) Many of the novel’s details of time and place I did cull from my own memories and then re-color, re-shape. I mean, how could I not use the hospital that sat abandoned (and lurking) during my most formative teenage years as one of the novel’s settings? It was just too ripe to skip over. But the specificity of Cam’s story—her status as an orphan, her particular interests and hobbies, her relationships with other characters in the novel, her time at conversion therapy—all of that belongs to Cam and Cam alone: it’s fiction.

Was Coley Taylor gay?

I have to put this back on you and say what do you think? (And does not knowing for sure ultimately matter to you, to your reading of the novel?) I’m more interested in a reader’s take on that question than I am my own.

But, but—since you’ll probably hate me forever if I just answer your question that way, here’s some stuff to think about: If we’re talking would Coley Taylor claim the label/identity gay, then no—clearly she would not, during the portion of her life shown in the novel, anyway—she plain refuses it anytime it’s offered or discussed.

In some ways, Coley takes the easiest route of all, which is just labeling all of that complicated, shifting desire as sin—sin pure and simple— and attempting to deal with it (deny it, really) that way.

However, that doesn’t stop her from romantically and sexually desiring Cam—and that’s what’s most interesting to me about Coley: desire and its many messy complications for someone who is attempting to live out identity types that don’t sit well with those complications. Coley’s particular brand of Christian faith, her role in her social circles, in her family, in this town—none of it fits, she thinks, with her attractions to/for Cam, and she can’t see how to make all of that stuff fit together.

She doesn’t believe there’s a way for her to be the Coley Taylor she so desires to be, and also to be a girl who is fooling around with Cameron Post. And so, in some ways, she takes the easiest route of all, which is just labeling all of that complicated, shifting desire as sin—sin pure and simple— and attempting to deal with it (deny it, really) that way. I personally don’t think she could pull off this kind of denial for the rest of her life, at least not totally successfully, but I can sure see her making a go of it. But I also don’t think, just because she had a kind of love for/with Cam, that doesn’t mean that she couldn’t have just as real kind of love with a man. Does that mean she’s firmly bisexual or pansexual something else, something more fluid, more resistant to any categories we might give it?

Maybe the question you’re getting at is what would 25 or 35 year-old Coley Taylor claim for herself— what would her relationship(s) look like—would they be with women, with men, with both? What do you think?

Did being an orphan exacerbate for Cameron Post the alienation of growing up gay in the American outback, or did it provide a sort of psycho/social excuse for her otherness that actually alleviated the coming out processs/non-process?

Wow—that’s a helluva question: nice! Unfortunately my answer is, well, both— it’s both something that further othered her and made her coming-out process that much more difficult, and it’s also something that gave her freedoms that she wouldn’t have otherwise had—freedoms and sometimes even excuses for certain behaviors/feelings, reasons not to really own them or even to consider them too carefully.

Because Cam’s first specific sexual act (the kiss with Irene) is not only one that’s fraught given its secret, shameful (she thinks) same-sex status, but it also quickly becomes one completely bound-up in her guilt over her parents’ deaths and her uncomfortable initial reaction to the news of those deaths, she spends a good deal of her early adolescence conflating her desire—and her coming-out process— with her status as an orphan. She’s already feeling guilty about her desires, and now she’s added this whole other layer of reasons to feel all the more guilty and ashamed of them—and that’s all mucked-together with her status as an orphan, in what she sees as her potential “role” in the death of her parents—even if she doesn’t always believe that she actually had such a role (or even that fate or god mandated it).

But, she also has certain freedoms as “the town orphan,”—and though she’s not always comfortable claiming that status, when she does, she can more easily use it to pass as “only” that kind of other — to, I don’t know, claim it as her trumping form of marginalization or something, and to keep folks from becoming too concerned with other aspects of her self. In that way it’s a kind of advantage, I suppose.

One of the characters who particularly intrigued me was Lydia the therapist, and I was wondering a couple of things. Firstly, did you envision her motivations as primarily bound up in her relationship with Rick? Or something else? Secondly, I wondered whether there was a reason why you made her British.

I imagine Lydia’s motivations as a therapist/ “healer” of those “suffering from same sex attraction” given particular personal urgency/importance because of her relationship with Rick. I imagine her as someone who was already interested in psychology and theology—studying those areas back in England—who was then was handed this “gift/specimen/research patient” of a conflicted gay guy who just so happened to be related to her (and whose own mother—her sister—had died.) And then, of course, her motivations would have been both as therapist and as family-member (and, well, Christian, of course.)

So starting a place like God’s Promise absolutely happened because of her relationship with Rick, but I imagine she’d have been very interested in these kinds of “therapies,” even without Rick has her nephew. She might have then approached it from a place of research rather than practice, and Rick gave her reason to devote herself to the practice of these very malformed theories.

She’s British because she’s a character partially inspired by Elizabeth Moberly, a British psychoanalyst whose very questionable “research” texts are often cited by various practitioners of reparative therapy. (Some of these books include: Homosexuality: A New Christian Ethic and Psychogenesis: The Early Development of Gender Identity.)

She was among the first psychologists to propose that homosexuality stems from developmental problems with a parental figure of the same sex and that the remedy to these problem is in developing healthy, functioning relationships with members of the same sex—not in forcing heterosexual attractions—those will develop “naturally” later, once these same sex relationships are established and plentiful. If you can track down a copy of the amazing (if dated) 1993 documentary about conversion therapy — which I mentioned earlier — One Nation Under God, you can see Elizabeth Moberly in all her British glory (though physically, and in many other respects, she doesn’t resemble Lydia).

NEXT: Choosing pop culture references, wondering about Cameron’s parents, targeting target audiences and a little extra-textual communication.

There are a lot of pop culture references in the book; did you have to much research, or were you mainly drawing from your own experience or some combination of the two?

I talked a bit about some of this when I answered the autobiography questions, but no, not really research (beyond making sure that my memory of when a particular song or movie was released lined up with Cam’s world— which it didn’t always) so much as considering my many options for those pop cultural touchstones of time and place. For Cam, many of these serve as reflections of her queer self—something she’s so desperate for. Some of the choices—of songs, books—are maybe more obvious and expected than others, but that’s what I was hoping for, a combination of the expected and the unexpected. So much of my adolescent experience was consumed with any and all popular culture available to me, so I wanted to get some of that consumption on the page, in the novel’s texture.

screenshot via “the miseducation of cameron post” trailer

What freedoms and/or limitations did you find writing a YA novel? Did you have a specific audience in mind?

Knowing your target audience, how did you choose which media to incorporate with Cameron’s character development?

This is a question that I get asked a lot, so I’m just gonna plagiarize myself here (I hope you’re cool with that): I would get absolutely zero writing done if I attempted to do any of it with an audience peering over my shoulder. The only audience I’m writing for—for the first couple of drafts, really—is me. I write the fiction I want to read. Really, my “target audience” is an audience of one—emily m. danforth, reader. That sounds a bit vain, for some reason, as I look at those words here on my screen, but it’s absolutely the case.

Certainly I’m open to feedback and criticism and suggestion, critique, a bit later on in the process, but nothing about the choices I made in shaping Cam’s voice or the novel’s situation(s) was dictated by me hoping to eventually reach as broad an audience as possible—or even one specific audience, for that matter. I just never thought like that. Despite the specificity of Cam’s situation—a recent orphan who is just discovering her attraction to girls while being raised by an evangelical aunt in eastern Montana (in the 1990s)—a lot of her experiences are pretty universal to adolescence (or adolescents, if you prefer): first crushes, first loves, first sexual experiences, rebelliousness, ennui, premature nostalgia. I mean, this is the stuff of one’s teen years, right? Some of Cam’s experiences are given more significant weight and importance in the novel because of the cultural, political, and religious climates operating in her small world (and because everything is colored anew for her since her parents’ death), but those experiences do ultimately have universal qualities.

I think Cam’s appeal might come from her near-obsession with sorting through her life, searching for small connections, puzzling things out, asking questions, making sense.

I also think Cam’s appeal might come from her near-obsession with sorting through her life, searching for small connections, puzzling things out, asking questions, making sense. It can be appealing to read from the POV of someone so curious about the world. She’s built of contradictions—overly romantic sometimes, world-weary others—but she’s ultimately, I think, generous and compassionate; she wants to find the good, the redeemable, in those around her, and when she does she recognizes it, even if that recognition doesn’t always last for very long or ultimately hold much sway.

Since the style in which I wrote this novel was, essentially, one of representational realism, I was much more concerned with the believability and accuracy of characters, scenes, and moments—wanting my readers to fall through the page and into the world of the novel—than I was with worrying too much about the relative comfort levels of potential readers (or their parents) in relation to the novel’s content. That sounds a bit more glib than maybe it should, but there were many moments (and fears and longings) from adolescence (my own and others) that I wanted to explore as fully and authentically as possible on the page, and I just couldn’t do that if I was also trying to censor or “leave out” those experiences because I worried about potential reactions to that material.

The book is pretty frank but not—I don’t think, anyway—in an exploitative way. I never “inserted” a scene of drug use or sexuality to be provocative or “risky” or really to do anything other than I want any scene in the novel to do, which is to honestly portray this character’s experiences with as much nuance and depth as possible.

[Do you answer extra-textual questions? If so, then:] When Ruth tells Cameron that Cam’s grandmother said she doesn’t want to see her, is Ruth being honest?

Sure, I’ll answer this (but now, of course, I want to know your thoughts, too). You’re talking about page 250, right, when Ruth and Pastor Crawford are confronting Cam with their news and her “sentencing” to God’s Promise? My answer is: yes, in that moment, Ruth is not lying to Cam—Grandma Post actually said (in some previous scene that isn’t in the book but that you can all imagine—one that takes place before Cam gets home from the lake that day), that she didn’t want to talk to Cameron (or presumably anyone) about this Coley revelation right then.

But, that’s the thing— it’s right then. The grandmother is of a much older generation, and she’s just heard this upsetting, to her, news about her granddaughter, and she needs to go deal with it on her own for a little while. She doesn’t want to think about sexuality in relationship to her granddaughter at all, and certainly not a kind of sexuality that she sees as perverse and strange, bad. It’s upset her, the news, as has her inability to make sense of it, to know what to “do” with it, and while she might not like Ruth’s methods, she doesn’t feel like she has any better ones of her own. So she goes down to her little apartment in the basement for awhile to just drown herself in TV shows about detectives and packages of sugar free wafers and to try not to think about what she’s just learned about her granddaughter.

Lots of people I know who are several generations older than I am—than Cam would have been—wonder why so many of us in younger generations “have to” talk about everything. These people often lived their lives believing that you just didn’t discuss some subjects, ever, not outside the home, but not even in it. Many of us now recognize the damage and implicit shaming this kind of silence can cause, but it makes sense to me that Cam’s grandmother’s reaction, one that would have felt safest to her, would have been just to try to forget it, to “hush up” about it, and certainly not to have confronted all of her unpleasant feelings with a discussion. However, when Ruth says (shouts) “She’s just sick about this, she’s sick about it!” Well, that’s Ruth’s term—sick, I mean. She may well be right, Grandma Post might have used that word herself, had she been there in that scene, but Ruth’s the one who’s putting it that way in that moment, who’s choosing to use that word.

How would Cameron’s parents have reacted to the news of Cameron’s sexuality had they been alive?

Well, I didn’t write that novel, so I haven’t explored all of that enough to give you a very satisfying answer. I don’t even really know how they’d “behave” as characters in a scene, since I strategically allowed for so little of their presence, as characters in this novel. Even when Cam is remembering them, it’s always in fairly brief chunks, not extended scenes. It’s the presence of their absence that I wanted readers to feel— so they aren’t even very vivid in her memories of them.

All of this is to say that I don’t feel like I “know them” as people (characters) well enough to answer this question with much nuance. They wouldn’t have sent her to conversion therapy, of that I’m quite certain. But they wouldn’t have thrown her a pride parade and started a local chapter of P-FLAG, either. Somewhere in the middle, I suppose. It would have taken them a period of adjustment, certainly, possibly a lengthy one, but they would have come around eventually.

Photo from the book about Quake Lake—”The Night the Mountain Fell,” via themiseducationofcameronpost.tumblr.com

If you could write another book from Coley’s perspective, would you? I’m curious about what her future would be like!

I tell you what, you and my wife should write that book together: she asked me the exact same thing not so long ago, but what’s funny is that she’d actually given much more specific thought to where, she thinks, Coley would be “today,” than I have—or than I had, at the point of our discussion, anyway.

She saw her as a well-to-do rancher’s wife living in Billings, MT—couple of kids, SUVs in the driveway, a comfortable “lifestyle”—but a woman who’s discontent, ultimately, and who often finds herself daydreaming about Cam, about those moments from high school, and also experiences these desires for other women in her current life, but hasn’t acted on them. Anyway, that was her (my wife’s) take.

It would be interesting to write from Coley’s perspective, certainly, but I don’t know if I’d want to do a whole book from it. I mean, it would be a fascinating exercise, for me, to just have her tell her story of this novel — but her version, which would be quite different, undoubtedly, from Cam’s. Every scene would change to reflect her own prejudices and memories and sense of the world. Maybe I would/could someday write a short story from Coley’s POV— the Coley of the future, that is, the grownup version — be she some rancher’s wife or not. No plans, as of right now, for that, but, but: you never know.

screenshot via “the miseducation of cameron post” trailer

What did you read growing up? What novels/poems/essays were influential in your development as a queer young adult?

As a pre-teen reader (and early teen reader) it was a lot of Roald Dahl, Beverly Cleary, Judy Blume, and dozens and dozens of those plot-driven paperback slasher/ thriller books by writers like Christopher Pike and Richie Tankersley Cusick— you know, The Lifeguard or Trick or Treat or Teacher’s Pet (that one was about a writer’s retreat, actually, and I completely loved it. Well, murders and a maniac at a writer’s retreat, of course.) I don’t know if any of those books specifically spoke to any queerness in me—though I suppose they must have, in ways I don’t know how to name—but I read them voraciously, and lots and lots of other books, too—I was reading always and with little discrimination, honestly.

Eventually, though, by sophomore year of high school, anyway, I became a bit more discerning a reader, and eventually sought out any lesbian fiction I could locate (secretly). A particular favorite for a long time was Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt. I still think that’s an excellent novel. And I was influenced, early, as well, by Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle. I recorded a little thing about my relationship to that book for NPR’s program All Things Considered. If you’re interested, you can find it here.

screenshot via “the miseducation of cameron post” trailer

Most writers are often advised to write what they know, and yet, so many writers who identify with the queer community still shy away from publishing works that can be labeled as queer or prominently feature a queer protagonist. Your novel deals heavily with queer identity as Cameron searches for reassurance that she is okay being who she is. How much did bringing more positive exposure to the queer community play into your decisions in writing this novel?

I don’t think that I was necessarily motivated to positively reflect one character’s process of queer desire, or, as you say, to bring “positive exposure to the queer community,” so much as I wanted to offer an honest and complete picture of Cam’s experiences, to fully render all of these significant moments from her adolescence, not just choose one or another to get at in the novel. Its power, if it has any, as a narrative, I think, comes from the specificity of its rendering and just how much of Cam’s life is there on the page. I didn’t want the novel to be reducible to one single element or plotline, as many “problem” novels are. It needed to be a much fuller exploration, one that seems to be, to readers, the whole landscape of these years, even though a novel —even a big one, which Miseducation is—can only cover so much ground. Cam is likable, I think, and I hope that she’s compelling, but I wanted, more than anything else, for her characterization to feel real to readers—to feel authentic, like she’s a living, breathing person and not just a heroic character that all queers can get behind. Cam is no spokesperson for all queers, of course, or all lesbians—and certainly neither am I. Neither of us want to carry the flag, that’s an impossible position.

But I agree with Dorothy Allison that the truest way to change someone is to get them to “inhabit the soul of another person who is different from them.” And fiction allows us to do just that. But not didactic fiction, which is necessarily one-dimensional, it has to be fiction that seeks to represent the world more completely, more accurately and fully, than does fiction that leads with its message and uses its characters as props for the message.

NEXT: On Cameron Post’s tumblr, how different things were when Cameron was growing up even though it wasn’t that long ago, what happens after the book ends, Taco John’s, Adam, NARTH vs. Music and more!

I would like to know your thoughts on the topic of guilt and contradictory feelings and how you explored those during your writing process.

I’m not sure if I understand the question, entirely (sorry for that—that’s one of the limitations, I suppose, of answering the questions this way and not just getting to be in a room with you chatting. Ah well, I’ll give it a go.) I honestly don’t have much to say about Cam’s feelings of guilt and confusion that’s not already there, in scene or passages of narration, in the novel.

You watch her wrestle with various kinds of guilt throughout the novel, and finally put some of that to rest at the end, there in Quake Lake. What I tried to do was, again, be pretty honest about her guilt and her areas of personal conflict and, as you say, “contradictory feelings.”

Cam, like all of us, doesn’t have everything figured out, and she’s fairly honest about that, I think, throughout the novel. She has desires and attractions that she doesn’t feel comfortable with, or that cause her more guilt, but still she acts on them again and again. And she does other things, too—the shoplifting, the dollhouse stuff—to try to bury some of this, or process it, but it’s all, frankly, sort of a mess and she just keeps pushing through it day by day. Until, of course, her stint at God’s Promise forces her to think about some of these things in ways she was previously good at avoiding.

After I finished the book, in a state of emotional distress/euphoria, I immediately went online to Google everything and see what was real and it was so satisfying to find “Cameron’s tumblr,” pictures of Miles City and so much more on your website. And that Quake Lake is real! My favorite was the video of the dollhouse. I’d love to hear the story of the real life dollhouse and also what inspired you to provide such rich content online.

via .emdanforth.com

Thanks so much! I’m thrilled, thrilled, thrilled that you located that extra content and have gotten some enjoyment out of it. Sometimes you put stuff up on the internet, you know, and you think: has anyone other than my web guy and my family ever even seen this stuff? Shouting into the void and all. (And yes, Quake Lake is very real and if you’re ever in Montana you should go. You must: it’s a supremely creepy place.)

At some point, shortly after the book sold, I was tooling around other author’s websites and trying to get ideas for my own, and I was always really jazzed about coming across “bonus content,” when I did, on those sites— especially if the author herself had a hand in it. (Carolyn Parkhurst had—or maybe still has—an entire website or blog written as if it belonged to one of her characters, who happens to be a very successful novelist. I loved that so much.) So I knew that I’d want to do that with my own website. And, I mean, I was as caught up in Cam’s world (for lots of years, while writing the book) as are, now, some of the folks who’ve read it. More so, I’m sure, since I was building it from memory and invention. It’s part love letter to my youth and to Miles City—though a bittersweet love letter, to be sure, so it was really fun to come up with more content for readers. It let me showcase some of my “favorite bits” from the novel. And I’m so excited that it did for you, as a reader, exactly what I wanted it to do.

As far as the “real dollhouse,” it’s not exactly the one described in the novel, of course (that came first, I found this “model” dollhouse for the video long after the book was already in galley form) but I thought it would be fun to offer some visuals to readers who sought them out. I would love it if someday someone would make me a real, scale, as described in the novel, Cam Post dollhouse. That would be one helluva labor of love, but I’d love it. I always wanted an authentic Victorian dollhouse—an intricate one—as child, as a teen, but I never got one.

Cam definitely focused more on the emotional side rather than the political side of being a lesbian, is there a reason for that?

I’m not sure that it’s so easy to reduce it to that binary—the political and the emotional, either or, sides of a coin. If the personal truly is political, then how do we separate those things, how do we extract those one of those from the other? Isn’t Cam making out with another girl in a barn during this time period a kind of political act, necessarily, given the culture around her? Or would it only be “political” if there was an audience—if it was staged as a protest or advertised as such? Does it need to be more confrontational, more transgressive?

For teenage readers who pick up the book today, Cam’s world is not, in fact, their world. I actually think of the book as a kind of historical novel.

My answer is that Cam’s not ready to take any of that on. She’s battling her own fear and shame about her desires and sense of self. I think Cam’s own answer to your question, though, comes on page 99 (and in the pages thereafter), when she’s discussing Lindsey Lloyd’s political passions and influence: as she puts it, she hasn’t “thought much” about any of that. Cam’s “lesbianism” (such as it is) is one born of desire, of her various attractions and actions on those attractions. It’s not that she’s not interested in feminism or theories of gender, of sexuality, of queerness, it’s that she hasn’t yet been exposed to any of that in any real way, and while of course queer desire is necessarily politicized, Cam wouldn’t put it that way. She doesn’t yet have access to that discourse.

I think there are many teenagers today who do have a mastery of those discourses, and Lindsey is an example of a teenager from that time period who, while often more interested in bluster than critical thought, is attempting a role as a kind of burgeoning activist, but Cam’s only real influence of this kind is Lindsey.

This is something that I was trying to “get at” in this novel in terms of its treatment of time and place. While there are certainly some universal themes of adolescence that translate well, I think, for teenage readers who pick up the book today, Cam’s world is not, in fact, their world. I actually think of the book as a kind of historical novel. Cam’s almost entirely cut off from the diverse kinds of queer culture that one can seek out, even if only online, today (Lindsey’s her one lifeline to those kinds of culture—beyond movie rentals, of course) and besides, politically and socially, the landscape of the very early 1990s is not, in fact, our landscape today, even just in terms of queer visibility, those twenty years are a looooong twenty years of change.

I mean, George H. W. Bush would be Cam’s president in this novel. Can you imagine him saying that he believes gay people should be able to get married? Are you kidding me? (In fact, when the novel opens, Reagan would still have been in his very final months as President.) This was a very different time for LGBTQ rights. Of course there was queer activism then, of course, but in terms of Cam having a real sense of it, given the town and state in which she lives, given her guardians, her age, what she’s told the Bible says about her: Lindsey is really all she’s got. And she’s very young, and she’s filled with guilt— some of that, as I explained in an earlier question, tied to her parents’ death— and it’s enough, I think, just for her to have to acknowledge and act on these desires she is not only told to suppress, but that part of her wants to suppress, to deny, just to more easily “get along” in the world. She’s young, frankly, and she’s just trying to figure shit out as she goes along.

What made you decide to write a lesbian coming of age novel? Does the book reflect any of your personal experiences?

I think I covered the “personal experiences” part in some other questions, but I’ll say here, too, that I’ve long been wholly enamored of the American literary tradition of the coming-of-age novel. I’ve read these novels since I was a very young reader and I still return to them again and again. I love books that chronicle a character’s initial attempts to make sense of the world and their place in it. I always knew that my first novel would tackle this material in some capacity, that it would be a coming of age novel. There are all kinds of ways to approach this material, to get at these themes, and I didn’t always know what shape mine would take, just that I’d write one. And I really do feel like I knew that early on, I mean, by high school, for sure. Despite that there are many, many excellent coming of age novels, and despite that some of those novels even chronicle the development of queer protagonists, I don’t feel like I’d yet read Cameron Post’s story as I wanted it told. And, as Toni Morrison says, “If there’s a book you really want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

via themiseducationofcameronpost.tumblr.com

I had a NARTH therapist for about three months and I know that the religion aspect with the psychobabble can have some long-lasting effects, but I’ve found that music played a huge part in my being okay with myself after my sessions. Cameron seemed to not have ever bought into the nonsense because of what Lindsey told her.

I’m glad to hear that music served that purpose for you, it’s powerful stuff, isn’t it—or it can be, anyway. I think, yes, that Lindsey’s strength, her determination to live some brave new way in the world — even when Cam recognizes it as somewhat performative — is crucial to Cam. Lindsey’s world, though she’s never experienced it firsthand, seems to be this other, waiting, option, basically, away from God’s Promise — Cam knows it’s out there, this one other life, in specific, and that’s important, in itself, but it also helps her realize that if there’s at least one other possibility for “how to live in this world as a girl who likes girls,” there’s got to be others too, right? It’s not just Lydia’s way or Lindsey’s way, there have to be alternatives to those, too, at that’s comforting to her, it gives her something to hold onto. And then, yes, just Lindsey’s micro lessons about queer history and culture, as insufferable as some of them likely were (if Lindsey got to pontificating, I mean) also gave Cam a sense of a wider queer community, one that she could potentially join if she could just last her time at God’s Promise.

via themiseducationofcameronpost.tumblr.com

What was the most challenging scene to write?

There were a few, really. The scene with Rick when he’s in Cam’s dorm room explaining the situation with Mark, that one was a challenge, it took some drafts. (Same with Mark’s actual breakdown during group session, actually. That one looked very different with each successive revision until I finally got the shape of it.) The entirety of the scene at Coley’s apartment—The Hunger/ sex/drunken cowboys scene, that is — that one was a challenge because it’s really pretty long—nearly twenty pages of actual, moment-by-moment scene, or close to, from the time Cam knocks on her door. And there were all kinds of things I wanted to get right in my portrayal there—the desire, the tension, so it took some finessing.

Do you miss Wilcoxson’s ice cream and Taco John’s potato oles? (from a fellow Montanan)

Yes I do, fellow Montanan: yes I do. I lived in Nebraska for five years before moving to Providence and I could still get potato oles there — I haven’t really been away from them for too, too long, so the longing isn’t as strong. (I mean, I’m not Jamie Lowry, you know, I only ate them a couple of times a year, at most. But they did certainly turn up with regularity in the eating habits of my adolescence.) But Wilcoxin’s: so good. There’s a toy store in Miles City, Discovery Pond, it’s right on Main Street, and they still serve it, and have a nice variety, so I sometimes get it when I’m back visiting. I’ve undoubtedly since had as good (maybe better) hard ice cream, you know, local stuff, handmade, whatever — but Wilcoxin’s tastes of my youth and always will.

via emdanforth.com

Do you think Margot eventually took Cameron in?

Do you think so? You do, don’t you? I like that. I like you. BUT, in material that I’ve written of Cam once she’s left Quake Lake, she doesn’t actually live with Margot, though she is helped out by her. Margot is the character who gets her this very weird job in this high end maternity mannequin factory— I mentioned that in my answer to a different question, I think. She helps Cam, certainly, she’s there for her, but she does not step in to fill the parental role.

I really enjoyed the Adam-Cameron banter, especially how they addressed (in a tongue-in-cheek manner) the tonkenization of indigenous identity and misappropriation of indigenous culture. Did you struggle with writing about Adam in a way that wouldn’t fall into the same meta-like trap of tonkenization, especially given the demographics of the characters?

What inspired the character of Adam?

Adam came to me in pieces, like lots of my characters, I suppose, but I was excited about the chance to use him to show the ways in which conversion therapy not only fails Cam or Jane, but also fails someone who comes from a culture that offers an identity category not only beyond those being sanctioned at Promise, but those “sanctioned” in much of the larger American culture.

I mean, Adam doesn’t give a shit about Biblical sin— his entire conception of being operates beyond most of the social and political structures of the country he lives in, much to his father’s annoyance/embarrassment. Also, I felt like it was important that every character in the novel not to be a white character, but, frankly, Montana is not a terrifically racially diverse state—according to the 2011 census it’s 87.5% white, and that number would have been even higher in 1991 — so I did worry that Adam might feel, to readers, like the token native character.

To work against that I did what I always do with main characters and tried to render him as completely and multi- dimensionally as I could, making sure that he was pretty crucial to Cam’s time at Promise, that he didn’t just fade from the novel after a single scene. I try not to deal in caricatures or stereotypes with any of my characters, frankly, but I’m glad to hear that having Adam comment on the commodification/misappropriation of indigenous culture added to his authenticity, and to their relationship. I mean, that’s where I start from, trying to render someone’s humanity in a scene, making him/her feel whole through dialogue and action and concrete, specific details of dress or mannerism.

How long did it take you to write the book and how long did it take to get published? Did you encounter any added difficulty in getting published because of its queer content?

These questions necessitate long, thoughtful answers, I think—but I’ve given them before, I swear. (Lots of people, not surprisingly, have these questions.) So I’ve cut and pasted, here, a lengthy answer that I gave about the publication process during an interview with the Debut Review, and then also part of an answer I gave when Malinda Lo interviewed me for her YA Pride Series this summer on her blog.

I “discovered” Cam’s voice, and some of the elements of her situation, in a short story I wrote during my MFA (at UMT in Missoula), but didn’t actively begin the process of shaping that material into a novel until my first couple of years in the Ph.D in Creative Writing program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. I didn’t work on it consistently during that time—I was also doing course work, writing short fiction, teaching, and so on— but I’d work on chapters or “chunks” and then workshop some of those and let some time pass, then get back after it. By the summer of 2008 I had over 700 pages “toward” a novel, but I wasn’t yet willing to call it a draft (it was missing crucial scenes and other kids of “connective tissue.”)

At exactly that time, in June, I took over duties as the Assistant Director of the Nebraska Summer Writers Conference (NSWC). NSWC director, novelist Timothy Schaffert, had read some sections from my manuscript—including the opening chapter—and he put in a good word with literary agent Jessica Regel, who was attending the conference as faculty, co-running a publishing workshop. (Jessica is at JVNLA, the same agency Tim’s agent is at—this is so often how these things work, these kinds of connections—and so his recommendation had a bit of weight to it, I suppose.) Anyway, I was to drive Jessica from Lincoln to Omaha so that she could catch her flight, and I managed to do a rather absurd job of that easy delivery— nearly running out of gas, getting us a little lost. (I should mention that I was flying to Massachusetts the next day to get married. So, you know—a lot going on.)

During that car ride, Jessica mentioned that Tim had told her a little about the book, and then she asked me to, essentially, pitch it to her. I know that, for a lot of fiction writers, this might seem like a dream scenario, but I was exhausted and therefore hopped-up on caffeine and we were nearly out of gas in the blazing Nebraska sun and I was panicking a little about that—this was not my dream scenario. I remember saying things like, “Well, it’s about this girl who, you know, she’s an orphan and she likes girls and she has this dollhouse and she gets sent to conversion therapy and Jane Fonda is there, but not the real Jane Fonda, and …” Really. It was awful. I mean, what novelist wants to summarize her novel? My standard definition for a novel is that the good ones don’t allow themselves to be very effectively summarized. And since I hadn’t even written a query letter (or anything of that nature), I didn’t have the rhetoric down, the approach.

Anyway, Timothy’s word must have meant much more to Jessica than did my inane blathering, because she told me to send her the first chapter (once I got back from my wedding, of course). So I did, and she liked it lots. But the issue was that I still wasn’t actually finished writing—or so I thought—so Jessica waited for a couple of months and then finally just asked me to send her the material that I was happy with. So I sent her what I then saw as parts 1 and 2 (which was still nearly 500 pages), and soon after we had a couple of discussions about how she actually felt that the novel was complete as is; that what I saw as just the resolution to part two could be finessed into being the actual resolution to the whole of the novel. So this was, you know, both completely thrilling and also took some getting used to. I’d had a particular conception of the arc of the novel for so long that ending Cam’s story any earlier felt rather impossible. But I thought about it, made a few revisions, and ultimately respected Jessica’s opinion, which was, basically, that we give it a go, and if editors passed because they felt like there was no real ending, or that the current ending didn’t work, we’d revisit the pages I wasn’t yet satisfied with.

So then we sent to several first-round places and we got several really nice passes (for various reasons) and even more suggestions that we “try it as YA.” This happened again and again—really, several editors said that they loved the book but that they couldn’t “get away with it” as adult and that we should send it to so and so at their YA division. This reaction was a surprise to me—at least the first few times (not so much by the fifth). This was mostly due to the fact that I just didn’t know enough about the diversity and depth of YA publishing at that time, and also because I’d read so many coming-of-age novels that were marketed as literary adult fiction and I felt like mine could potentially fit in there somewhere. However, ultimately what I wanted was for my book to find an audience, and I was equally excited to think of this book being marketed to and read by teens—especially when I thought of 15- or 15-year-old me and what this novel would have meant to her.

At some point Jessica and I had a formal conversation about all of this. I really hadn’t thought very “strategically” about this part of the process. I wanted to tell Cameron’s story, to create a novel that would allow you to live in her world, to see her wrestle with identity formation (and death and love and sex and …) Other things too, of course, but potential audience and the ins and outs of publication were just not the things that guided me as I’d worked on this book for all those months. Lots of writers have talked about this—about eventually having to take off the creative hat and put on the business/marketing/professional writer hat—but since this was my first book, it was all brand-new to me and I didn’t know exactly where to find that hat. (Or if I even owned it.)

So then we eventually sent the book around again, this time to some YA editors. This is going to sound a bit new-age-y, but the energy really was different, better, this time around, and soon thereafter Alessandra Balzer at Balzer + Bray made an offer. We spoke on the phone and she was charming and funny and really “got” all of the things about Cam’s story that were important to me. This will probably sound a bit naïve, but really it was that she talked about this book—about my book—the way I talk to people about novels that I love. There was something very genuine there, in her response, and I knew that she was the person, and Balzer + Bray was the imprint, to make all of this happen. No question. And really, everything since that decision has been a dream. It’s all been new and whirl-windy and sometimes quite overwhelming, but I feel pretty damn lucky about it every single day. (And if the many email messages I’ve received from teenage readers are any indication, this novel was absolutely published with the correct “designation.”)

And as for its queer content as a YA book, in fact, the specifics of Cam’s “miseducation” — her time in conversion/reparative therapy, that is — actually probably made the book more saleable than less, simply because it’s an intriguing and unfortunately timely topic. My experiences with everyone who worked on the publication of this book were overwhelmingly positive and supportive, and never once was I asked to tone down or change content because it was too controversial or risqué or what- have-you. There was simply no pushback regarding the queer content anywhere in the process (as I’m aware of it, anyway).

Was it difficult to end the book at Quake Lake?

How did you decide to end the book where you did? Would you ever consider writing about what happened to Cameron later in life?

How did you go about writing the ending? Did you have a couple options you tested out, or did you know from the beginning this was how it needed to end? When you get to know a character like Cameron, it’s hard to say goodbye as the reader. As the writer did you want to just keep going?

Well, fact is, I did “keep going.” There are another two to three hundred pages of Cam’s (mis)adventures filed away on my hard drive. I actually began the book at what I thought would be a place much closer to its ending and then worked backward from that, though not in a linear fashion, it’s just that I discovered Cam’s voice and some elements of her character while writing a short story that I later thought would become a scene that happens after Cam leaves Quake Lake.

It’s complicated, all of this, and probably too much to go into here, but while I knew pretty early on that Cam would eventually visit the lake, absolutely, and have some sort of ritual there — try to find some peace from that experience — I initially thought that might be the end of the second part of the book, and that it would be a four part book. So part one would have been everything in Miles City; part two would have been God’s Promise; and part three would have been this life she leads after leaving Promise — it involves a maternity mannequin factory in southern California, that’s all I’m saying; and then part four would have been her return to Miles City to deal with Ruth, who by that time was very, very sick with complications from her NF.

But, I mean, that novel would have been 1000 pages, easy. And it became clear to me at some point—through the advice of my agent, mostly—that that novel was not going to end up being this novel. But that this novel could still work. So, all of that is to say: the final chapter, the final moments, in fact, of that scene, went through many, many revisions (both before they even got to my editor and then with her—it was a section we worked on quite a lot) and material was cut and material was added and finally we got to something that I’m very proud of and that I think works for this novel.

But, I haven’t fully said goodbye to Cameron. I’m very happy to be writing something else right now—a completely different book, no traces of Cameron Post to speak of—but she’s still around on my hard drive. I don’t know, for sure, what will become of those pages, but perhaps, someday, a companion book — “the rest of her story.”

emily m. danforth in a canoe via www.emdanforth.com

Now it’s your turn. Did you have a Lindsey Lloyd? Do you think Coley Taylor is queer? What happens next? Were you struck by how long ago the 90’s are in queer years? Had you heard of The Hunger before this book and if not have you checked it out since? What was your favorite part? What are all of your feelings you’ve ever had about this book? Don’t you think Emily Danforth is amazing for answering so many questions? You guys, she started answering questions at 9AM EST and now it’s 10PM EST, just saying.

Oh and, Sonia F., email carrie [at] autostraddle [dot] com with your full name and shipping address, because Lindsey Lloyd has a care package for you!

Pages: 1 2 3 4See entire article on one page

EPIC CAMERON POST POST IS EPIC.