This piece was originally published on 12/14/15.

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual. We will be celebrating Pride as an uprising. This month, Autostraddle is focusing on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. Instead, we’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

“The holidays are a tough time to release your inner child into the meadowlands of black conceptual art.”

The “30 Americans” exhibition now showing at the Detroit Institute of Art is an extraordinary opportunity to see the work of some of the most important contemporary artists working today. Everyone who can see it should. Take your nephew. Take your grandmother.

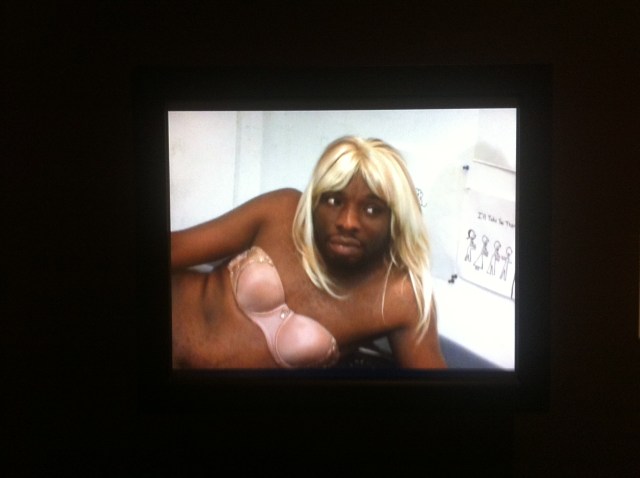

Carrie Mae Weems brings some Susan Sontag-style Regarding the Pain of Others analysis to a series of slave daguerreotypes. In a small screen in the corner of a room, William Pope.L crawls along the sidewalk in a Superman costume to inspire someone, somewhere, to think about the lived reality of homeless people. Iona Rozeal Brown helps us navigate our complicated feelings about the fact that sometimes, Japanese hip-hop artists wear blackface. Kara Walker still wants you to go ahead and try to act normal in front of one of her murals. Just try to smile politely at a stranger while you are standing in front of one of her murals. Hank Willis Thomas does not seem like the kind of guy who thinks that black athletes, by being rich, negate questions about branding and ownership. I have loved so many of these artists for so long. Kehinde Wiley? Kalup Linzy? Lorna Simpson? They deepen our conversations about race and gender and violence and value in a moment when we direly need to deepen our conversations about all of these things. Etcetera, etcetera.

Viewer feedback at the DIA

This is not what I’ve come here to talk about.

As I listened to the audio tour, narrated by Touré, I felt a few things. First, I was underwhelmed. I mean, I loved Touré’s profile of Lauryn Hill in Never Drank the Kool-Aid, but it’s not like he had a whole lot of creative control in this audio tour. The snippets were short. A lot of them involved student responses to the art, when I wanted to hear more from the artists themselves.

Let me preface this by saying: I wasn’t in a great mood that day. It was the Tuesday before Thanksgiving and I was visiting my family — going to a midwestern winter climate from a desert “winter” one. When this happens, I forget how to exercise and I don’t understand what to eat for breakfast. Upon entering the museum, my father and I got into a minor scuffle with one, then three security guards over whether or not my dad’s selfie stick was indeed a selfie stick if he thought it might be used as a “unipod.” I hissed at him, “don’t make a scene,” and then I realized from the way they were looking between me and my dad and back again that the security guards weren’t so much comforted by my presence as they were invisibly sucking their teeth at this coddled biracial kid who didn’t know how to respect her elders. Somebody looked scared—like she was shielding her son’s body from us. Also: there were about five hundred student groups that day. I kept doing that thing adults do in the face of adolescent swagger, where you act like you’re so above it and then you walk into something.

As we got our tickets, my dad nodded his head in my direction and said, “she’s five” in the hopes of paying a cheaper fee, but also in a way that, in retrospect, may have been revenge for me not siding with him in the selfie stick situation. Then, a woman told me, with very intense eyes, that I looked just like Frida. I love Frida Kahlo, but do you ever feel like when a white woman gives a young black woman a compliment with a certain expression on her face you can hear the soundtrack to The Help playing in the distance? Or, I don’t know, Out of Africa? See, I told you: I WAS IN A BAD MOOD. The holidays are a tough time to release your inner child into the meadowlands of black conceptual art. I tried to eat a rootbeer flavored taffy, but my inner child stayed put. So, maybe I was looking for a fight.

On Facebook, I was about to the make the mistake of engaging with a racially charged comment thread. I would actually have to post that Thanksgiving Adele Saturday Night Live video in a gesture of peace. More globally, though, in about twenty-four hours, a white supremacist would be shooting five Black Lives Matter protesters in a city I always thought of as exceptionally tolerant. Paris happened. Beirut had happened. Donald Trump exists. There was something in the air.

From Carrie Mae Weems’ “You Became a Scientific Profile/ An Anthropological Debate/ A Negroid Type/ & A Photographic Subject (from From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried series), 1995-1996” with Kara Walker reflected

So, as I walked through the exhibition, I started to wonder: what exactly is it about this show that feels funky? There was a missing context. It felt, somehow, opportunistic. Vampiric in a way, as if the premise was, simply: black is hot right now. But that couldn’t be it — not realistically. Shows like this take a long time to plan, and this was a travelling exhibition that only just now got to Detroit. The Black Lives Matter movement wasn’t even a glimmer in Patrisse’s or Alicia’s or Opal’s eye when the show came into fruition. So why was I not convinced?

Something flickered for me around the time that, in my ear phones, one of the collectors who put on the show, Mera Rubell, asked Shinique Smith about her piece, “a bull, a rose, a tempest.” The work consists of a collection of items—a shoe, a bag, some kind of camouflaged fabric — hanging from the ceiling. When something hangs from the ceiling like that — lumpen, hogtied, reminiscent of a body — there is a visceral quality that makes you want to spend some time alone. In the interview, what Mera Rubell decides to ask is, “Do you go to specific places to get these rags?” And Smith responds, “I don’t really call them rags.”

Now, the kind of frustration I feel toward Mera Rubell’s interview style isn’t on par with, say, the frustration I feel toward Ted Cruz’s homophobic pastor affiliations. The Rubell interviews hold many moments of racially complicated dissonance similar to those Facebook arguments you might have with somebody who does not seem to have encountered any race theory or even considered the possibility that there is some literature to have read up on before diving into that Meryl Streep suffragette tee-shirt kerfuffle. Just, like, five minutes of bell hooks. The frustration I feel toward Mera Rubell’s interview style is rooted in the experience of listening to someone who holds a lot of power, whose title is “owner,” ask questions they don’t care to hear the answer to of people whose intelligence feels tripped up and cornered by the mediocrity of the asking.

Film Still from Kalup Linzy’s “Conversations wit de Churen” Series

In “America,” Glen Ligon created a neon sign wherein the tubes are painted black, while the light is bright white. The effect is that the lettering is outlined, limiting the incandescence. Mera Rubell says, “This piece — you wouldn’t make this piece today.” She says, “somehow this piece is a pre-Obama moment.” When somebody says “pre-Obama,” I don’t feel far from the phrase “post-racial.” Ligon explains that the piece was inspired by Charles Dickens. When he says, “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” Mrs. Rubell joins in. Yup. He continues,

I started thinking about the moment when we went to Afghanistan, thinking how interesting it is when they go to Afghanistan, these reporters go and they interview people on the street who say “Your bombs dropped here and killed my brother and destroyed our house and I want you Americans to live up to your ideas of democracy. We believe in America.” And I thought how interesting is it that America can be this dark star, death star, and also at the same time this incredible shining light.

Viewer looking at “Hotter than July, 2005” by Mickalene Thomas

At a literary conference last March, Eunsong Kim gave a talk about the trials and tribulations of Carrie Mae Weems and her series, “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried.” Apparently, Harvard University threatened to sue the artist for using the daguerreotypes of enslaved people originally commissioned by Louis Agassiz because Harvard owned these images. Kim challenged the audience to think about the question of ownership here, given that the images themselves portray the bodies of slaves. When encouraged by Weems to have this conversation out in the open, the university declined.

My sweet father purchased for my spoiled ass, “The Conversations,” a DVD about the “30 Americans” exhibit including extended interviews with the artists, and I have been watching with my face contorted into a grimace, the way you would watch, perhaps, Khloe and Lamar. Or certain episodes of The View.

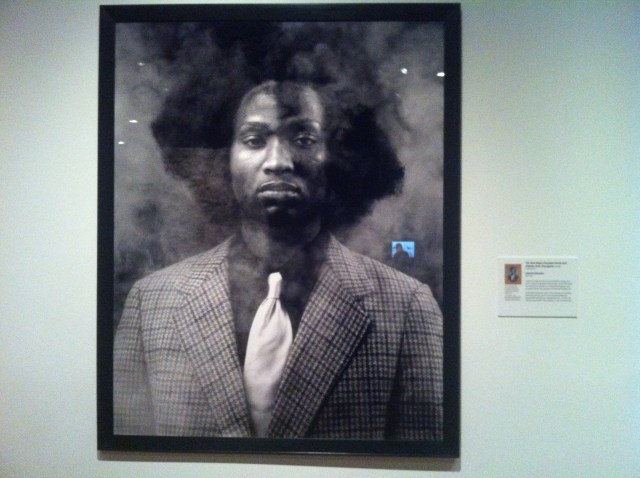

Some artists do a beautiful job of owning the awkward room in which they have been beckoned to perform this chit chat. I say “perform” and “chit chat” because these interviews feel perfunctory rather than curious, contained and at times corrective when the artists have so much more to say than the space knows what to do with. If you want to know what the subtext of this interaction looks like, check out Rashid Johnson’s “The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood)” — in which a black man stands with an expression of utter imperviousness as smoke rises around his Frederick Douglass-style hair.

Rashid Johnson’s “The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood), 2008”

I give credit to Jennifer Rubell, the daughter of the collectors, for editing the video in such a way that tries to honor the manner in which these artists assert themselves. The film begins with Kerry James Marshall energetically questioning the concept of power. “There are no black collectors that I know of that can do what you just did in having an exhibition like this,” he says to the collectors’ faces. And, “How much analysis, how much criticality are you bringing to the essays in the catalog?” He goes on to say that the title of the exhibition, by avoiding mention of blackness, feels like a lie: “You’ve tricked them into coming here.”

After we leave, my father and I get some hot and sour soup. We visit Dell Pryor’s gallery on Cass Avenue, where the work of Kara Walker’s father, Larry Walker, hangs on the wall. During Thanksgiving dinner, my (white) mother will ask my (black) great aunt if she is tired. To which she will respond, “That’s why the white man don’t let the n***** eat until after he works the field.” The room will be quiet for the smallest second before exploding into laughter. It always fascinates me that in the humor of this 94-year-old woman, the ante-bellum era exists in present tense. The owner and the slave and the field as clear as day.

Thanks for this review. I keep intending to go see this but haven’t had a chance yet. Hopefully soon. Definitely a different perspective than I have gotten– a Facebook friend just posted what seemed like a glowing review. Your thoughts are valuable. I’ll be thinking about your perspective when I attend.

The art is totally worth it– I absolutely recommend going! I feel a giant glow for the art and the artists.

Awesome! That’s what my friend was saying, it seems you’re more critical of the way the exhibition was put together and presented and how the artists are forced to perform for it as you say than the art itself. I’m excited to see the art!

I’m seeing that, other than Cincinnati later in 2016, there are no other stops for this exhibit. Wish someone was bringing it to the west coast. :(

I going home to Detroit next week, Monday. And this is the very first thing on my to-do list!!

I’ve been waiting to see it for months! I made my family go right when it opened. Can’t wait!!! So excited!

i just loved this, is all

Thanks Carmen!

Thank you! I think I might be able to go see it now, and take this review along with me to help me focus on what the artists are sharing and not on the presentation and filtering and all that. Why is it in a museum? It’s sort of baffling, how much we can’t see what we’re doing.

Thanks for this, Aisha. I’m not near Detroit, but from the pictures and descriptions that you’ve included, it sounds like some amazingly thoughtful art…and some not-so-amazingly problematic narratives and institutional frameworks constructed around it (as those of archives and libraries can also be).

Ay, that parting comment…

Wow… just wow. This is incredibly written. Phenomenal writing. Really, this piece blew me away. It’s the best writing I’ve ever seen on this site and I think there are a lot of really good writers here.

Thank you, Aisha. I will definitely be looking for more of your work.

This was incredible

This was fantastic. You’re a beautiful writer and I really value your powerful responses to this exhibition.

Oh my goodness, thank you for the love! I have the chills.

this was amazing! so excited to get to see more of your writing and hear your voice!

Welcome, Aisha!

Such powerful words…this piece is beautifully written.

Thank you!

this was amazing!! thank you.

I didn’t comment earlier, and I meant to. This was really fantastic. I’m so excited to see more from you.

lovely writing style!

Thank you for writing about this. I left 30 Americans feeling frustrated – not at the art or artists but at the museum and the way the works were contextualized. There was an emphasis on how this work was responding, reacting, ‘sampling’ from European art traditions but so very little about the conversations between these artists which have been ongoing. Lovely to read your perspective.

I’m so glad to hear that you had a similar response– it’s an interesting issue that I’ve seen in the literary world, too. Sometimes the folks who act as gatekeepers aren’t as clued in as you’d hope they would be about the content of what they are exhibiting and it’s just such a weird dissonance.

It was affirming to read this after feeling similar frustrations at and about the contextualization of black art in a variety of contexts. As well as agitation with the way in which white folx fail to address my race and their inherent white supremacy, lack of understanding, and poor excuses for “action”.