It happened five years ago. She was my first girlfriend. I had never had sex before; I had been out since I was in my late teens. I thought it couldn’t happen to me, because I thought it wouldn’t. How could a woman, let alone a queer woman, sexually assault another woman?

That question was the first of many I’ve encountered in a five-year process of healing, rage, and research. But the question I most often get—and still receive, to this day—is one of confusion. When I tell people I was raped by a girl, they ask me: What does that mean?

It means she put her fingers inside me when I didn’t want her to. It means she held me down. It means she would grind or trib on me, when I didn’t want her to. She went down on me, when I didn’t want her to. She had sex with me when I was too drunk to say no, when I said no, and when I was too scared to say anything. She told me it was my fault. And she didn’t stop. Not when she quit drinking. Not when she came out to her family. And she didn’t stop trying to hurt me, even after we broke up.

When I finally went to the local sexual assault crisis centre, I was lucky enough to find a counselor who got it. “You sound exactly like a woman who was raped by a man,” she told me. I was destroyed. I wanted it to be different. Wasn’t it different, when it was a woman? It wasn’t, and it isn’t. But there are definite factors that make sexual violence and survival different between lesbians. Access to sexual health education, crisis support services, and health care, and the ways that heteronormativity, substance abuse, internalized homophobia, rape culture, and misogyny affect our communities, are just a few of those factors.

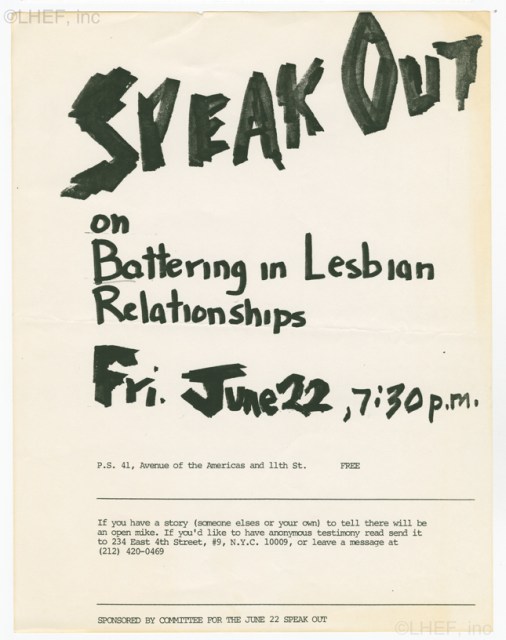

Image courtesy Lesbian Herstory Archives, subject files, abusive relationships folder

Did I feel like I had to protect my abuser by rationalizing her behavior? Of course. Did I feel like I had to defend her in order to defend our queer community? Absolutely. Was I afraid no one would believe me, not only as a lesbian survivor of violence, but also as a femme? Totally. Did I feel completely betrayed? You bet.

Sexual assault by a woman affected my mental health, my sex life, my friendships, and my activism. It affected my writing and my performances as a poet. I stopped going to the gay bars and the Pride parade in my hometown to avoid my abuser—I thought if I avoided her, it would just go away. But she came into my workplace. She came to my readings. I couldn’t avoid it anymore—I had to tell my friends and coworkers why I was suddenly in a cold sweat and hiding out in the bathroom. Sometimes, I still have to tell people.

Like many survivors, I’ve since learned that most of my friends and coworkers had long suspected there was something going on in my relationship that was harmful. But the warning signs and red flags for abuse in queer relationships manifest in ways that can be subtle or different from what we expect in heterosexual relationships, and what we see in the media. I know my reaction to some classic red flags, as a lesbian, was one of denial or misrecognition. I even interpreted the concern of my allied and loving parents as bouts of latent homophobia. They didn’t think my relationship was wrong because it was between two women — it was wrong because it was abusive.

As for my next few dates and sexual partners, their reactions were nearly as bad as the initial assault: How could you let this happen? It’s not like she hit you. I heard victim blaming and disbelief, even from women and queers who had supported partners and friends through man-to-woman sexual violence, or who were survivors themselves. It didn’t seem to matter — something about me, about this, was different.

Coming out as a survivor of queer sexual violence was, and is, more difficult than I ever thought coming out as a lesbian would be. I couldn’t find anyone else telling their story. Where were our lesbian feminist foremothers? Where were Audre Lorde or Adrienne Rich when I needed them? I turned to zines— Support, by Cindy Crabb, and The Revolution Starts At Home, which is now an incredible anthology in book form. My counselor found me a resource guide developed not for survivors, but for local crisis support providers, about lesbian domestic violence. And then I started writing. I couldn’t write a manual, but I could write the poems I needed to read.

When I was accepted into the 2012 Lambda Literary Retreat on the basis of this manuscript, I didn’t know what to expect. I went to L.A. for eight days, where I met Dorothy Allison, who writes in her book Two Or Three Things I Know For Sure: “I am a woman who must speak plainly about rape . . .I am the woman who must love herself or die.” Jewelle Gomez, the revolutionary Black Indigenous lesbian feminist poet, read excerpts from my project, and understood exactly why it mattered. We talked about why second-wave lesbian feminists, and especially women of colour, might have had their stories of in-community violence met with stigma or silenced. After I met with Gomez, I went and sat in the canyon by myself, in shock. Someone got it. Finally.

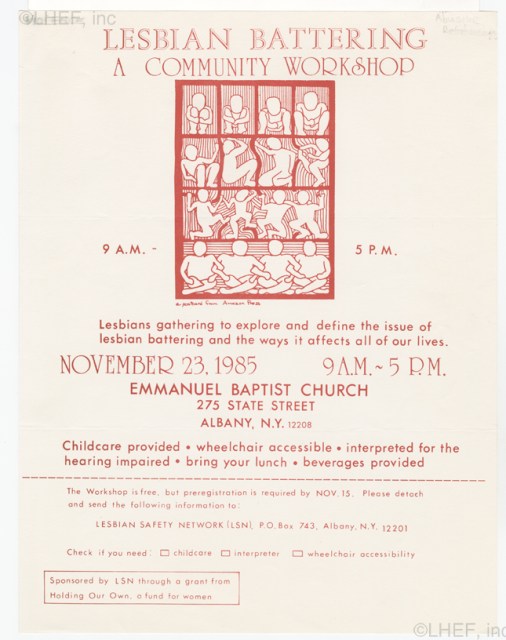

Image courtesy Lesbian Herstory Archives, subject files, abusive relationships folder

A year later, I secured travel funding to go to the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn to back up my project with some original sources. I was terrified, thinking that the archives would reject my project with the same sort of “That doesn’t happen in this community!” mentality that I so feared at home. The response couldn’t have been more the opposite — and this time, I was going with the support and company of two of my dearest friends, poets I had met at the Lambda Retreat. I spent a whole day at the archives, and I was astonished by what I found, and what I didn’t find. There were entire subject folders labeled “abuse,” “abusive relationships,” and “domestic violence” — all about violence between queer women. Posters for support groups from the early eighties and nineties, news articles, and leaflets all talked about lesbian battering as a feminist issue. I found early documents from the former Network for Battered Lesbians, founded in Boston in 1989, which is now The Network/La Red, an American resource and model for LGBTQ organizations beginning to address partner abuse. But when I went through all eight folders entitled “rape,” I couldn’t find anything about lesbian women experiencing sexual violence perpetrated by other lesbians.

In the absence of those materials, I found what I was looking for—confirmation that lesbian-to-lesbian sexual assault is a story that needs to be told, and an issue for which we have to create our own archives and resources. But first, we need to acknowledge that it happens. In-community sexual assault is a reality in our lives as queers. Silencing, shaming, and avoidance won’t help anyone. At least, it didn’t help me, and it certainly didn’t make it go away. I hope the more we talk about sexual violence between queer women, there will be less confusion and stigma, and more awareness about the factors that make this a distinctly queer and feminist issue. With that awareness, and acknowledging that we as lesbians are not immune to the perpetration, survival, and witness of sexual violence in our communities, we can work together to develop support and education around consent for queer women, and leave a legacy for younger lesbians to rely on. I think this can happen, too.

Leah Horlick is a poet and writer living on Unceded Coast Salish Territories in Vancouver, BC. A 2012 Lambda Literary Fellow in Poetry, her writing has appeared in So To Speak, Poetry Is Dead, Grain, Canadian Dimension, and The Bakery. Her first book, Riot Lung (Thistledown Press, 2012), was shortlisted for a Saskatchewan Book Award.

thank you so much for this. thank you for the strength to share it, and the space to start a conversation. it is sorely needed.

much love and solidarity-

Thank you for sharing your story. I admire so much that you have made something creative and strong out of your trauma – I am working, ever so slowly, towards that goal. Your story is so important, and I hope that if someone needs to read this, they will find it.

<3

Leah!

<3

I love this so much. All I can think to say is thank you for writing.

Thank you so, so much for writing this.

thank you for sharing. this is.. so much. thank you for trusting us with your story.

Thank you for sharing this. It’s so important and yet such a difficult thing to discuss, so thank you for starting the conversation here.

Thank you for saying it “out loud.” I thought I was the only one.

Thank you

As always you continue to amaze me Leah. Thank you for sharing this. <3 <3 <3

It feels like an even deeper betrayal when we are hurt by our gay partners. If a person understands that rape is not about sex but about power, then this should not be a revelation. I’m sorry for the trauma you suffered but thank you for coming forward and for sharing your story.

Thank you so much. I know how hard it is to talk about this stuff. You’re amazing and strong.

Just wonderful. I think its so brilliant that this sort of thing is finally getting talked about. I hope that in time and as we start to build a stronger, more unified queer female community, these experiences will not be so silenced and so alone, we will support eachother.

You mention worrying that people would not believe you because you were femme. I think we underestimate how heavily gender roles play within our community. Equally, when someone more along the MOC or transmasculine spectrum is assaulted, there is the assumption that somehow that person couldn’t be assaulted, in fact it was more likely they themselves were the attacker.

Thank you so much for having the strength to write this, as well as the courage to share it.

Thank you for being brave and for sharing this. I hope you know how important this piece is.

Thank you so much for sharing this

Thank you, thank you, thank you for speaking out. While my experience was way less severe, it took me 5 years to realize that my first time having sex was actually forcible and can be considered rape. It was perpetrated by my girlfriend, who I was sexually attracted to, and I was naive and thought that made it different. I would have called what happened to me rape if the scenario was straight couple.

I agree with what has been echoed here – that I didn’t want to shatter my illusion of a safe gay space where these things just “don’t happen”. Thank you for bringing attention to this!

Thank you for sharing your story. =) I know it’s hard to believe these things happen, and sometimes we need a reminder. lots of <3

Thank you for your courage in identifying your experience and sharing it with us! I can absolutely identify with your struggle, and I think a lot of my queer/lesbian identifying friends don’t realize how many of us experience sexual abuse perpetrated by our partners. Your insight is lovely, thoughtful and encouraging and I hope to share this article with anyone who might need to feel like they aren’t so alone.

Sexual assault and abuse is about power; it doesn’t matter what the sex or gender is of either the abuser or the victim. But you’re right, there is a lot of denial in, not just our community but society at large, regarding any type of abuse or assault that’s not male abuser/female victim. This needs to be told. Thank you.

Long afterwards, I sometimes wanted to scream, but couldn’t bear the thought of metaphorically waking the neighbours. Better to stifle it with a pillow, I thought, than to have my desperate entreaties met with embarrassed silence. I hate the way people do that: treat news of sexual assault with stony or shrugging muteness. It was the silence of utter abandonment, a weightless space into which my shame and self-loathing boomed, resounding in a million echos. A single kind word and an understanding ear might have been all that was needed to stay the hemorrhaging of my heart. But for whatever reason, none dared.

I think… Groups which believe in rhetorics of innocence are intrinsically wont to shroud their violence. When we convert our besieged identities into tribes which say, “Our hands are clean; it’s all THEIR fault”, our responsibility is absolved by the “evildoers”. We leave no space for recognition of our own communal culpability, let alone the compunction needed to hold perpetrators accountable and heal abuses. In-group violence is simply left unrecorded and unchecked in the name of a greater politics. We are all left dangling, silent, without a language which allows survivors to cry out their pain.

When we say, “This is utopia”, we almost always end up banishing evidence of contrary reality to the shadows. And the shadows do grow. Sometimes they grow to the point where victims are routinely sacrificed to the communal delusion; Renee Girard painted this dynamic well. Of course, such a pattern is recognizable in cults, dysfunctional families, and Orwellian nations. But those of us who have suffered the “safe space” of certain women’s communities may see the pattern at work there, as well…

So, for me, witness-silence and victim-blaming are deeply linked to communal delusions of cohesive purity. Women may admit to physical violence. But in the rhetoric of lesbian/feminist communities, women are sexually innocent of rape, which is the special sin of The Patriarchy.

Thank you for drawing attention to this issue. Your courageous gesture enriches us. I hope your project brings much fruit in opening up discussions of sexual violence in Queer women’s communities.

Brighid, thank you for a keenly intelligent and beautifully written comment, it has struck me deeply.

“Groups which believe in rhetorics of innocence are intrinsically wont to shroud their violence.”

Beautifully said. It can apply to the discussion at hand, and so much more.

In my opinion,’I was raped’ is the hardest thing to say out loud.

It sticks in your throat like a bad dream.

I cannot imagine / am ashamed to say I hadn’t even thought to try to imagine following that up with “by a woman”, and trying to maneouvre the mine field of reactions from something that seems to have a reaction ready made for male female dynamics.

Thank you for sharing this, for giving me food for thought. I hope you continue building yourself a new world within the parameters of being a survivor, you are braver than you will ever know.

It takes so much courage to share stories like this. Thank you for sharing yours!

thank you so much ive struggled with the idea that this may have happend to me but thought it couldnt be .. i was attracted to her .. i to a point wanted to be with her .. but when it came down to it i was really drunk and she wouldnt take my NO serious .. i just keep telling myself that it wasnt wrong because i had wanted it until i didnt.. that it was ok because she was drunk to and just didnt hear me when i told her no over and over.. that it was ok because i gave in and let it happen but i know that if years later it still bothers me as much as it does it wasnt ok.. i dont know that im willing to say i was raped maybe im in denial about it but i know now that i didnt give consent even if i didnt fight her once i said no she should have respected that … reading your story made me feel like it was ok to have all these feelings that ive had for so long … Thank You

Thank you for this brave, honest and sadly necessary article. Please know that we stand with you. I don’t know if it helps at all when you’re being shamed and blamed for something that wasn’t your fault at all, but there is a community of women from around the world who believe you and support you and have your back.

Thank you so much for your courage and openness in sharing your story!! Your bravery opens the door for so many queer women after you to also feel like it is okay to share their story. You’ve done a very powerful thing!!

Thank you again.

It happened to me, too.

Or, it might have. I don’t want to commit to saying it did, because that would make me a victim, and being victimized clashes so much with my sense of self that it’s easier just to rationalize what actually happened.

It was my first time, too. My first girlfriend – long-distance, now meeting face-to-face, alone in my dorm room with my clothes slowly being peeled off. Having been out for 5 years and perpetually single, I so wanted this relationship to work; I wanted to prove to my skeptical friends and family that I was a happy college student capable of having a normal relationship. Minutes before I had experienced my first kiss. (She told me I was bad at it.) She kept going and I wasn’t ready but I could tell that she wasn’t going to stop and so while I thought it, I didn’t actually say “no,” because once you say no and the person keeps going – that makes it assault. So instead, I relaxed and told myself to enjoy it, which I kinda did, but not really.

Later that week there were times where I really did say “no” – but in a joking, please-don’t-make-this-so-awkward tone, unwilling to take a harder stance because, again, that would redefine us from girlfriends to victim and abuser. So even when she dug her fingernails into my arm and yanked me over to the bed, I didn’t resist. Even when she would slide her hands down my pants in public areas without my permission, I would quickly pull them out but not admonish her for it. The bruises were signs of passion, the soreness in my genitals a reminder of sweet orgasms.

She had been abused as a kid, I rationalized. She just didn’t understand what was appropriate.

And I still tell myself these things because although the relationship crashed and burned pretty quickly – or never really left the ground, depending on whether you consider a week of fucking to be a real relationship – we remain distant friends. I insisted on that because lesbians are always friends with their exes and what we had was a short-lived but NORMAL relationship, okay? Because to admit how much she hurt me would make me a victim and I will NOT be a victim. Instead I prided myself on how much I’d learned about sex in that week. And dammit, I’d had so much practice that no one would ever be able to tell me again that I was a bad kisser.

That was six years ago and I’ve been single and celibate ever since. To deny the legitimacy of that relationship would mean that I’d have to admit that I’m approaching 30 without ever having had a girlfriend. And with my body issues, low confidence and self-esteem and tendency to cut myself off from the world, well, who’s going to want to date an undersocialized, almost 30-year-old woman whose only experience with love and sex is in the context of abuse? As time ticks on and crushes go unfulfilled, there’s also the creeping suspicion that maybe she was it for me, maybe I won’t ever have another girlfriend – so I sure as hell am not giving up on the one I had before!

That would be too pitiful. And I’m a strong, masculine-identified woman, I don’t want pity. Pity is for victims and I am not a victim.

And with my body issues, low confidence and self-esteem and tendency to cut myself off from the world, well, who’s going to want to date an undersocialized, almost 30-year-old woman whose only experience with love and sex is in the context of abuse?

Please, take life at its own pace, be good to yourself, and follow your intuitions and desires and healing process. But when you are there, I can %100 guarantee, that there will be people who will want to date you. And love you.

Dear Jess,

as a child I was sexually abused by my mother, grandmother, aunt and also male family members. I completely forget that this happend to me, because otherwise I wouldn’t have survived.

I had several lesbian relationships but none lasted longer than a year. Then my girlfriend would break up with me and I didn’t understand why that happened to me. I completely lost myself in each of these relationships and felt devastated after a break-up.

At age 37 I had the feeling that there was something wrong with me and I started therapy. One baby step after another I found out, what happened to me.

It took me nine years of therapy to accept that I’ve been a victim of sexual abuse. At the beginning of my healing process I felt very angry. Even today, I sometimes feel very angry. But this anger helped me to look into my past and find out what happened to me.

It also gives me strength to fight for myself and my interests whenever it is needed, today. I can’t change that I’ve been a victim once. But with the knowledge I gained during my therapy and the insights I got, I know that I can help other people who are victims of sexual abuse.

During this process I wasn’t able to have a relationship and today I am longing for a soulmate. But there is also this fear to open up to another person. I could get hurt, again.

I also know, if I don’t take that risk and open up to other people, I will always be a victim and nothing will change.

I want to change, so I speak out loud – or write in that case – about me and my experiences. Maybe it is only to show other people that there are more victims than they can imagine.

By breaking the silence you took the first step to show to yourself that you are strong. It takes a lot of courage to write about the things that happend to you.

And it took a lot of courage for Leah to start this post and writing about her experiences.

So thanks to Leah and to you for breaking that silence.

“She had been abused as a kid, I rationalized. She just didn’t understand what was appropriate.”

This is what makes describing abuse at the hands of a woman so different to me from incidents with men. I had an experience with an acquaintance who, knowing that I had a low tolerance for alcohol and tended to party with a buddy for safety’s sake, volunteered to go with me as a buddy to a party, waited until I was incredibly drunk, offered to let me crash on her couch and then basically assaulted me after I passed out.

She had obviously planned the whole thing and later told me that this was just how people hooked up, she’d hooked up with several men that way. I had a strange combination of feeling totally disgusted by this woman who violated me yet also thinking she wasn’t some villain, she was just a pathetic product of rape culture. It still feels confusing describing it to people.

Great job on this article. Please write more.

Thank you, Leah, for writing this, and thank you, Autostraddle, for providing a platform to talk about this.

Thanks.

I find that so often in the queer community, misogyny is normative and looked over with the excuse of “this behavior is ok as there are no penises involved.” Which is frankly, far from true.

You’re a warrior

This happened to me too, though with rather different circumstances – by another woman at an all-women play party. Wearing a slutty outfit. Would have been my first experience with a woman sexually. Pretty much the poster child for ‘she asked for it’ if people could get past the idea that a woman could rape another woman. I developed vaginismus from it for a few years and couldn’t even look at dildos until very recently.

It took me a long time to come out with the story – slut-shaming, ‘you should have known better’, one person who used it as a tool to manipulate me to give them more attention. I did find some support, but so much of the resources out there assume rape by Guy In Bushes; everything else was in itself erasing and slut-shaming. What was I doing in a sexually charged environment? How much did I ask for it just by being there? How can a woman rape another woman?

What surprised me most about the whole thing was my reaction: my first strongest impulse was to find other women to fuck. I didn’t want this to be my only experience. I wanted something better. It took a year (and a bad breakup in between) but oh god was it sooooo worth the wait. But zomg! I wanted more sex! I must have not really been raped because real survivors become celibate! gah. so frustrating and painful and confusing.

I clung onto Slutwalk and got heavily involved because it was the first major resource and movement that affirmed and validated my story. No need to qualify it, no need to make justifications, no need to explain myself. (Sadly the year after I told my story at Slutwalk someone who used to be a friend said my story was ‘inappropriate’ and ‘triggering’ because of the location of the assault, and that I was ‘alienating’ survivors who weren’t kinky. WTF.) Thank god for all the Slutwalk organisers around the world who held me and my story.

Thank you for sharing this. <3

thank you

I cannot reiterate enough: Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Thank you for this article. It happened to me, too, and it doesn’t get talked about enough. I do want to say, however, that even though it is SO important to tell these stories, I think it’s also important to be mindful of details that can be triggering to people with issues like PTSD. Just a short trigger warning (for example, “Trigger Warning: Rape”) at the top of the article, before you go into detail about the abuse, would have let me decide for myself whether I was in the right “place” to read it. (I started reading because I thought you were going to talk about the issue without going into specific detail.)

Good point, K. It did trigger my PTSD but at least I have learned some tools to deal with it.

Thank you so much for writing this.

I’ve found that the abuse by my mother is questioned more than that of male abusers, and when I did video evidence recently I completely left out the repeated assault by not-ex of mine.

I wanted to date her so much, I crushed on her so hard I thought I would stop breathing when she lay on me, I wanted to run away and never see her again and kiss her simultaneously and when it came to dating someone else, I worried if I didn’t fancy them as strongly because I didn’t feel the same thing – because I wasn’t scared.

I’d like to say I got some sense and left. I didn’t. I tried to ask her out and she told me she was dating someone else moments before, I grew angry with her and swore not to speak to her for a year. It wasn’t the last time I saw her, but it marked the beginning of the end of that year and a half.

My experiences with all my (sexual, but also other) abuses put together have caused so many problems in almost every area of my life, some caused by women, some queer – sexual or gender – and some biologically male.

It frustrates me when people say ‘men are evil’, or they blame the patriarchy. It eliminates so much of what is happening from the picture. Personally, I don’t believe people are evil (admittedly in part because it helps me think I have more power than I do over situations).

Even if I did believe people are evil ‘men’, as a collective group, are not – in my opinion – evil or bad. Some people do bad things. Some men are very good and some are not people. The same goes for all other gender variants.

Personally, I’ve been sexually abused by cis- and transgendered people. By males and by females and over all, I just have really bad luck.

Also, I wrote a fairly lengthy (more so than this one) reply about my experiences with said girl and I feel it has helped me process it a bit, especially since I don’t normally talk about it. So I’d like to thank Leah both for her own activism and article and also for providing an opportunity for me to think about how and why I allowed it to continue.

Thank you.

(I haven’t bothered reading the comments yet) This brought tears to my eyes. Thank-you.

The first three paragraphs mirrored my first sexual encounter/physical relationship. While I felt uncomfortable at the time, it wasn’t until six months later that I made the connect that what she had done to me… was rape. Sure, I had said no prior, had tried to dissuade her through “nice” comments (“I’m tired.” “maybe later.” “I’m not really in the mood right now, how about we sleep?”) but because I never screamed or pushed back, because I gave in to her wishes, I assumed I was just “easy.” At 20 with no prior experience, how was I supposed to know that “want to come back to my apartment and hang out?” was lesbian code for “I’m going to fuck you”?

Unlike you Leah, I didn’t even bother to seek counseling or help. I just assumed that no one would be able to help me as all anti-sexual assault talks and workshops at my college and community were heteronormative. And sad to say, I fear your experience proved my apprehension correct. It was not until I discovered feminists on Tumblr (and how I found this article!) that I began to understand what sexual assault and rape really were, and how to recognize my experience as abuse, and consequently how to talk about what I went through. And sadly, 2 years later and this is the FIRST article I’ve found directly addressing sexual assault between queer women.

THANK-YOU for this. Thank-you, thank-you, thank-you. I cannot express how grateful I am for this and for your own work. And I am also so sorry you had to discover the trouble of what it means to be a victim of women-women sexual assault. I hope more queer women find the courage to speak in their own time about this issue.

It happened to me, too, and even the person I chatted with at RAINN after the fact blamed me for it. Guess how many people I’ve told since then? And that was seven years ago.

Thanks for writing this. I know it couldn’t have been easy.

Thank you for sharing this story. As this happened to me and it is a story that needs to be shared and heard.

Although neither of the two women who have sexually attacked me were able to go as far as what you described, I feel very unsafe in the LGBTQ women’s community because of the many incidents I’ve experienced. I have also experienced a large amount of sexual harassment and stalking by women.

The worst incident involved a situation in 2006 at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival in which I was aggressively kissed by a woman named Ann from Minnesota who had spoken to me socially once or twice. (I am outing her here intentionally to protect others whom she may meet. She had long brown hair when I met her.) I was so shocked by her behavior that I didn’t say anything – I just stepped back and she backed away.

Just to put this in context, I am a very sex-positive person. I am also very consent-oriented.

I have also been stalked in various ways by at least four women. One of them used to call me on the phone five times a day.

The sexual harassment occurred later and happened mainly in professional networking contexts in a queer-friendly city. I counted numerous incidents – boundary violations were happening to me almost every other week.

When I went to an LGBTQ-friendly support group and brought up the fact that women had been grabbing me in bars and I felt unsafe, I was asked to leave the support group because I might upset the people who were newly coming out. Apparently, talking about personal safety issues in bars was bad PR for the queer community. I later complained to a senior manager at the organization; she grudgingly apologized.

I ended up making the decision to stay out of sexuality-related community events of any kind, for the most part, while I was living there, because it was impossible to prevent women from bothering me.

When I have talked about these incidents to people, they have never believed me. My girlfriend asked me to stop discussing that this was happening altogether. A woman in the community completely denied my experience at the festival could have happened. A therapist told me that I was sexually harassed on a train by a woman because of what I was wearing, even though I was wearing jeans and a hoodie at the time. A relative said, “You’ve always been very attractive.”

Now, a reality check: I am neither drop-dead gorgeous, flirtatious, nor into wearing unusually sexy outfits.

As someone who believes consent is important, I believe women *should* be able to be gorgeous and flirty without fearing for their physical safety in the LGBTQ community, though.

The extent to which both queer and heterosexual people have minimized my experiences and blamed me for being sexually harassed, stalked and attacked by women is unconscionable.

If we had the courage to devote a small amount of the money we spend on fighting for queer marriage to preventing rape, stalking, and related boundary violations within our community, then I’d be much more proud to be out of the closet than I am today.

Frankly, today, I am somewhat ashamed of my membership in the LGBTQ community because of these incidents. I do not feel safe in this community and I may never feel that way again.

So yes, these stalkers, harassers and rapists are getting what they want. They want people to think women don’t harm other women. They want people to think events like the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival are safe. This makes it easier for them to create a culture of denial where they will never be held accountable for the damage they do.

Thank you. Thank you, thank you, just… thank you.

My first queer relationship was emotionally abusive and left me feeling extremely distraught and empty. I guess that made me a very easy target at the one lesbian bar in town. As a result of being raped by a queer woman — a sister of all people! — my interest in romantic or sexual relationships of any kind has plummeted extremely, something my (also queer) friends simply don’t understand. I don’t want to explain to them every time why I don’t want to go to Lesbian GoGo Night this or Free Girls Night that, but this is just the life I have to lead now.

What hurts even more is that the majority of people I’ve talked to about this (read: most of my therapists) don’t even consider what happened to me to be a “real” rape. Because “women can’t rape.”

The worst thing is the fear of literally everyone. I was already very wary of men due to past experiences (read: realized I was a lesbian in a Catholic high school full of entitled knobheads), but now I’m genuinely afraid of anyone that could even have a chance of being sexually attracted to me. Being flirted with by men or women still makes me nauseous even though it’s been six months since it happened. The sheer thought of going on a date with someone terrifies me, especially if it’s more than four subway stops from where I live. But I can’t talk to anyone about it because if I do, I’ll get one of two responses:

1. But how does that even work?

2. [cue homophobic rant about how all gays are fucking rapists]

And nobody ever. EVER talks about it. Which is why I’m so grateful that I found your article. I spent so much time thinking I was alone.

Through my work I have known many butch women who blamed themselves for the emotional and often physical abuse at the hands of their feminine-appearing partners. The reality is these butch women internalize the false belief masculine-looking gay women are more likely to be the violent abuser to their more feminine significant others. They are not.

They are, however, more likely to be ostracized, marginalized and stigmatized. Women’s perceived value and status correlate to their beauty in the eyes of males.