Queered Science is a series of profiles meant to highlight queer science and tell you what you need to know about it, for your intellectual edification and so you don’t feel excluded from a major and predominantly heterosexist subset of academia and industry.

Header by Rory Midhani

One of the main drives behind this series, as you might have already figured out, is to introduce smart science queers to all the other smart science queers who exist. Now, you might be thinking, shouldn’t there already be some statistics about us — some kind of survey or self-reporting count? The Internet exists, it couldn’t be that hard, right?

And if you were thinking that, you would be right, we could indeed self-report and count ourselves, and that has just been done by two smart science queers named Jeremy Yoder and Allison Mattheis. They just finished gathering data in a nationwide survey of sexual diversity in science, technology, engineering and math professions, called Queer in Stem. This is the first study of its kind, and the first research focused on scientists above the undergrad level.

The illustrated Yoder and Matthies, hard at work among wildflowers. (via Anna B. Hall)

Jeremy is an evolutionary ecologist doing his postdoc research on natural selection on the genetic code of a Mediterranean wildflower at the University of Minnesota. He did his Ph.D. at the University of Idaho. He’s gay, and out “in pretty much every context you can name. I grew up in a religious background, and I came out relatively late in life, only after I’d started my Ph.D.—starting grad school was when I actually started to meet and make friends who were gay. So my experience in science has really been that it was a place where I was free to be myself.”

Allison is an educational researcher, and just finished her M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota. She says, “I’m queer and anyone who spends any time with me will probably find out pretty quickly (people often read me as straight, however, because I’m a cisgender woman). I get that ‘what, you’re gay?!’ kind of reaction a lot which is annoying. As a middle-class white woman who works on issues of intersectional identities and social justice, I try to use that experience to remind myself not to make assumptions about other people, and also recognize the privilege(s) I have and use it to speak up.”

The two met and became friends when Allison hitched a ride to work with Jeremy’s carpool one day. Jeremy had been wondering about issues of LGBTQ equality and inclusion – he did some preliminary hunting on Google Scholar and couldn’t find any studies looking at people past the undergrad stage. (You might remember our article on Dr. Erin Cech and her study on LGB undergrad engineering students’ experiences — and her study was the first of its kind as well). Allison had done some work on queer issues previously, on “discrimination in school settings, transnational queer migration, and identity development.” So Jeremy asked Allison what she thought about the idea of a survey of a nation-wide sample of queer scientists – as a social scientist, did she think results like that would be publishable? “I responded, ‘are you asking me to teach you about doing research with human subjects? Sure!'”

They just published the preliminary results of the Queer Stem survey and answered some questions for me about what they have seen so far.

What have you learned from your results so far?

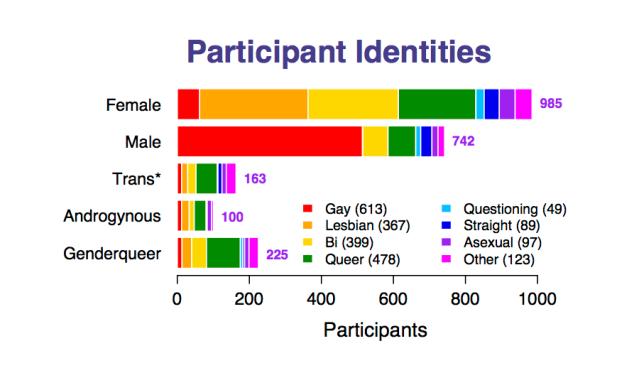

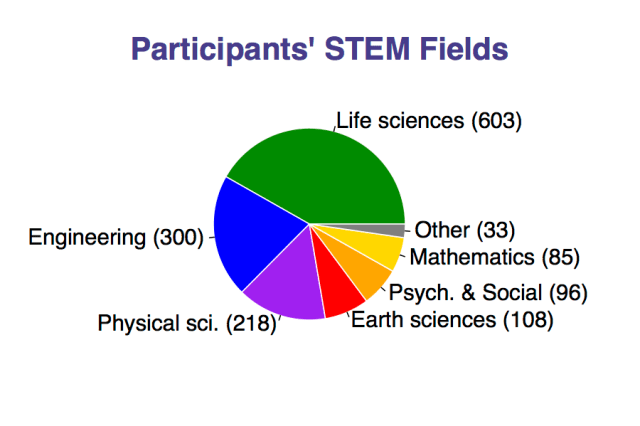

We’re only just starting to crunch the numbers, but what we’ve seen right off the bat is, there are actually quite a lot of queer people working in STEM fields. Over 1,400 people participated in the online survey, from every major region of the U.S., and even quite a few from overseas. We have representation from every major STEM field, and participants of all ages and career stages. And we have good representation of folks identifying outside the gender binary—11% of participants identified as trans* and almost 16% identified as genderqueer.

From their preliminary results, the self-reported identities of those who answered the survey. via queerstem.org

We’ve also begun preliminary analysis of the open responses and interview data (in addition to the survey over 140 people responded by email to ten open-ended questions and we interviewed 60 people individually). The quantitative and qualitative data both suggest that there are some very specific things that can make a big difference to people’s experiences, for good or bad — like whether there’s formal institutional support for LGBTQ people, or whether people are able to identify mentors or role models with similar experiences.

Again from their preliminary results, the STEM fields we work in. We’re everywhere, you guys! (via queerstem.org)

What are the most interesting leads/threads you’ve noticed either in the analysis of your data or in carrying out the study itself?

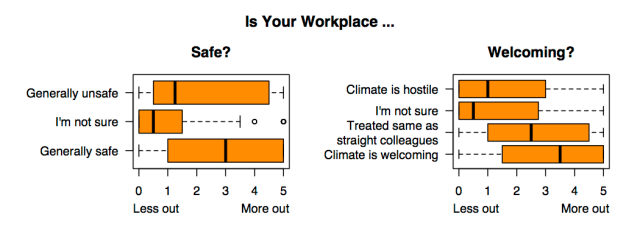

Jeremy: Across STEM disciplines, we saw people are mostly very out in their personal lives, but less out to colleagues or students. Interestingly, the factors that seem to predict how out people are in professional contexts aren’t the size of the school where they work, or whether they work at a private or public institution, or even the part of the country or the size of the town where they live; what makes a difference is whether they rate their workplace as safe and welcoming, and whether their employer provides benefits and support for queer folks.

Interestingly, the question is: do people come out because they feel safer to do so, or does the work environment feel safer because they, and others, have come out? (via queerstem.org)

Allison: I’ve begun identifying particular issues that seem relevant to most of the participants and those that are more specific to particular people’s experiences. For example, whether or not respondents report having regular interaction with a supportive queer community outside of their professional work is an external factor that impacts both personal and work life. Individual characteristics like gender identity, a racial or ethnic minority, age, and religion are significant for some participants and less so for others.

How have your peers/advisors/etc. in academia responded to this study?

Jeremy: My boss has been very supportive, and interested in what we’re seeing. That’s been my experience in talking to straight colleagues across the board, really. And, in fact, I’ve been asked to present results from the survey as part of a seminar and discussion series on diversity in biology that’s been organized by the College of Biological Sciences at my university.

Allison: The response has been great and people are very interested in learning more about our findings, both in my field and beyond— I’m that person that tends to meet you at a party and then talk your ear off about research.

Caption: Yoder and Mattheis – last-minute survey recruiting at the Twin Cities Pride Festival earlier this year (via Jeremy Yoder)

Where do you hope to go from here?

Jeremy: We’re hoping that we, or someone, will be able to do a follow-up version of the online survey in the next couple years. That would let us start to estimate how many queer-identified folks are actually out there working in STEM, and how representative our sample is. There are also all sorts of new questions we’d like to ask, or questions we’d like to ask in a different way, now that we’re starting to look at the survey results in depth.

Allison: We have had many people (both respondents and other researchers) write and tell us how excited they are that we’re doing this study and that has been really great. In my new position as faculty, I’m also looking forward to being able to mentor graduate students with interests in these issues, and to hopefully involve students in our ongoing analysis and writing. [Allison just accepted a position at California State University, Los Angeles in the division of Applied and Advanced Studies in Education, so if you’re anywhere near there, watch for new work from her!]

What do you hope for in the future of academia and social justice?

Accessible to people of all identities, ethnicities, and economic backgrounds. Science works best when it’s informed by a wide diversity of perspectives. We also hope that queer research and advocacy efforts will be enhanced by greater recognition of how many LGBTQ individuals are out there doing innovative and valuable work in STEM fields!

i have met so many other babygays and homoqueers and every other sort of lgbtq+ person while working/studying biology. it’s a little more than a little wonderful.

(weirdly thrilled that 16% of us in STEM id as genderqueer! i’m a genderqueer person who has often struggled with the internalized notion that having a non-binary identity was … gosh, i don’t know troublesome, i guess? wishy-washy and unnecessarily fussy. of course, that was never a standard i applied to others, but late at night, when i was overthinking everything, i can’t deny that it was something i thought about myself. but seeing that so many others in this field carry a non-binary identity! somehow that makes me feel validated. scientifically supported. i can’t explain it, but it’s nice.)

Pretty cool survey. I would be interested to see information about the involvement in STEM careers of trans men and (particularly, as I am one) trans women. It’s hard for me to parse these results in a way that reveals this to me. I’m also curious about the question structure that led to the sex/gender break-down of “male,” “female,” “trans*,” “androgynous,” and “genderqueer” for the test subjects. If I had been asked my sex or gender and those five options were presented to me, I would’ve said female, as would a lot of trans women, I’m guessing. But it’s possible (just speculating here) that the researchers had more complex or more numerous gender-related questions, and they non-consensually classified all trans women as not at all being “female” but as only being “trans*.” Which would have been messed up if not surprising. I guess I’m honestly just a bit frustrated that the researchers appear to perhaps view being female and being trans as mutually exclusive, and that AutoStraddle’s science writer has no commentary about this. But again, I’m not surprised. . .as the belief that while I may look female, I’m not ACTUALLY female is one that most folks seem to share, both outside and inside the queer community, and use to justify various forms of discrimination, exclusion, and othering toward me. Comes with the territory I guess.

I was also wondering about this, so I took a look at all the numbers they gave on their website. If you add up the number of answers to the gender question, it comes out to more than the total number of respondents. I’m assuming this means people could choose as many options as they wanted, although if anyone has alternate explanations for the numbers they should definitely post them.

I also wondered about your question as I wrote this piece, but as Jeremy Yoder writes on the website: “we let people choose multiple terms for both gender ID and orientation—and there are a lot of folks who did.” You’re right, it could have been clearer, so thanks for pointing that out!

Thanks for the info, Vivian. Thanks Adrian for your response also.