Welcome to the eighteenth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to [email protected].

Header by Rory Midhani

Last time on More Than Words, we toured the history of English pronouns, ostensibly as a classical prelude before diving into the endless quest to make some room in this language for gender neutrality and non-binary alternatives. But as I was beginning that checkup, it occurred to me that I hadn’t been asking enough questions. In fact, I’d skipped a really basic one: why do some languages, including English, have gender woven into them in the first place?

It’s not a foregone conclusion—plenty of languages, such as Farsi, lack grammatical gender and gendered pronouns altogether, while others, such Spanish, incorporate it to such a degree that people are resorting to punctuation to get around it. That English falls somewhere in the middle (largely gender-neutral but for the pronouns and some fraught exceptions) is a testament to its weird history. It also makes it a really cool test subject going forward. An explanatory detour*** seemed in order. Here’s how gender got into our language — and how it crept almost all the way out again.

AN ILLUSTRATION OF GENDERED LANGUAGE

What is grammatical gender?

First of all, let’s define some terms! Specifically the term “gender,” which linguists use differently than most people. If a language has grammatical gender, the way that German and French and Icelandic do, each of its nouns is sorted into one of several categories. When you use a given noun in a sentence, any word that refers back to that noun (adjective, pronoun, article) changes to agree with the noun’s category.

About one fourth of the world’s languages use grammatical genders. Although many of the gender categories fall along a masculine/feminine/neuter divide, some don’t! For example, take Dyribal, an aboriginal Australian language with only a few dozen native speakers left. Dyirbal has four grammatical genders, which linguists refer to as male, female, edible, and inanimate, but even that is pretty approximate — for example, class II, the “female” class, actually contains women, fire, things related to water, things related to fighting, and most birds. (Cognitive linguist George Lakoff’s famous book on categorization, Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, is named after this).

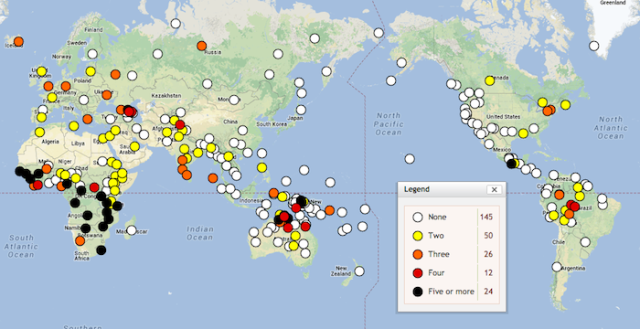

THE WORLD ATLAS OF LANGUAGE STRUCTURE’S MAP OF GENDERED LANGUAGE DISTRIBUTION (DOTS REFER TO NUMBER OF GENDER CATEGORIES)

The World Atlas of Language Structures sampled 257 languages and found that 112 contained grammatical genders. Of these, fifty had two gender categories, twenty-six had three, twelve had four, and twenty-four had five or more. Linguists call these categories “genders” because that’s always been the term for this sort of noun class. This makes more sense when you learn that grammatical gender came long before the idea of psychological gender, which we will definitely cover in a future column, because oh my god, talk about blowing my mind. But for now! Let’s talk about grammatical gender baby/let’s talk about you and me.

LET’S TALK ABOUT ALL THE GOOD THINGS AND THE BAD THINGS IT COULD BE

How did gender enter language generally?

Lots of linguists have theorized about why early language speakers felt the need to split their nouns up into different treehouses. Louis F. Klipstein, in his 1840 treatise Analecta Anglo-Saxonica, guessed that it was a result of “fetichism”:

“…which recognizing the Deity in every thing, even in the smallest blade of grass, seems to have prevailed in the earliest times over the whole earth. From fetichism there was an easy transition to polytheism, which made almost every natural object, as well as every mental faculty and moral affection, a separate divinity of either the one or the other sex.”

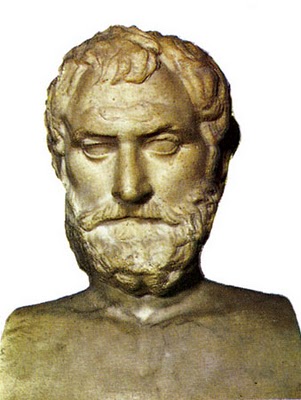

But the best concrete proof we’ve got points toward a philosopher named Protagoras. He was a 5th century Greek rhetorician, famous for being a radical relativist (he coined the phrase “man is the measure of all things,” which freaked everyone out, as did his other masterwork “there are two sides to every question”). Plato started searching for his famous Ideals just to flout Protagoras and his friends. But this relativism did not keep Protagoras from being obsessed, like most humans, with categorization. When Aristotle published his Treatise on Rhetoric, a work that helped solidify the rules of spoken and written Greek, he included, as part of his advice on “purity in speaking your language,” the “essential… distinction Protagoras marked out between the genders of nouns, viz. masculine, feminine, and neuter; for it will be essential to have these correspond correctly.” Fun fact: Protagoras shot himself in the foot — he actually said “humankind is the measure of all things” but the translation has been mostly scanned as “man,” possibly due to his own own legacy of gendered words. Nice try, Protagoras. Do better next time and we’ll name more than a moon crater after you.

FUN FACT #2: PROTAGORAS’S MOON CRATER IS LOCATED IN THE “SEA OF COLD”

This answer sparks more questions, though: why masculine and feminine as categories, when EVEN someone raised in a binary-worshipping culture, unschooled in gender theory, with nary a jot of awareness of Autostraddle Dot Com, could EASILY see that so many things (e.g. chairs! flowers! glasses!) don’t easily fit into either group? Linguists think it’s because humans talk about each other so much more than we talk about anything else. According to Lera Boroditsky, a cognitive psychologist at Stanford, “things that [are traditionally considered to] have a biological sex are hugely disproportionately represented in the set of things we actually talk about.” (About 60-70% of the nouns we use in daily conversation are words like “mother” and “uncle” and “girl.”) “The fact that that’s such a strong and coherent set of things… creates a really strong anchor that pulls the rest of this stuff in conceptually.” So maybe when Protagoras was deciding how to categorize, he was swayed by this (and maybe it’s also how it caught on so quickly and stuck around so long). There’s also evidence that Protagoras considered things without biological sex to have inherent gender-related qualities, as he once criticized Homer for treating the words “helmet” and “wrath” as grammatically feminine at the beginning of the Iliad.

HOMER WATCHED THE RIGHT TV

Grammatically gendered languages that grew on their own, without Greek, have their own stories (Khoekhoe, for example, has a masculine/feminine/neuter split and developed entirely in Southern Africa). It’s amazing to me that this method of categorization occurred independently in so many places. I’ve focused on Greek because it’s a Proto-Indo-European root language, and so English may have gotten its original gendered-ness this way, via some circuitous route that probably involved a healthy dose of Latin (as many early and befuddled English grammarians used Latin as a guide).

Was English ever grammatically gendered? What happened?

Yes! I’m glad you asked. Many centuries ago, back when it was Old English (though its speakers probably didn’t think of it that way), English had grammatical gender. We even had gendered forms of “the” — for example, you’d say “se mona,” because the moon was masculine, but “seo sunne,” because the sun was feminine. So why don’t we anymore? According to Anne Curzan, who wrote a book called Gender Shifts in the History of English and says things in interviews like “I probably have studied the loss of grammatical gender too long to give you a good succinct answer,” grammatical gender was usually indicated in Old English by inflectional endings — basically suffixes, like the modern “-er” or “-ism”. Old Norse was the same way, but the inflectional endings were slightly different.

OFF WITH YOUR HEADS AND YOUR INFLECTIONAL ENDINGS

Around the late 11th century, as the Vikings were invading Northern England, speakers of Old Norse and speakers of Old English were running into each other a lot, and probably trying to communicate. Since the two languages had a lot of roots in common, in order to understand each other better, “people may have deemphasized these inflectional endings, which were already weak, and then maybe they just dropped away,” taking their grammatical gender signification with them (this is similar to what happened to the extra “e”s you see all over Olde Englishe Poetrye). At the same time, word order was becoming more fixed, which took away some of the utility of, say, subject/adjective agreement — if you always put a descriptive adjective before the noun it’s describing, there’s no need to make their endings match up. By the 13th century, grammatical gender in English “was kind of limping along.”

Why did English keep its gendered pronouns?

…Except, of course, for those third-person singular pronouns, which were in fine shape. There are a couple of likely reasons for this. First, pronouns were too short to be affected by the aforementioned inflectional haircuts. Second, people had been flouting the rules for pronouns for centuries already. Even back in the days of grammatically gendered Old English, speakers had tweaked their grammar so that masculine and feminine pronouns lined up with the sex of whoever was being described. One example: weef, which meant “woman,” was actually a neuter noun in Old English, and so would have technically gone with neuter pronouns and adjectives — in real life, though, people used feminine pronouns anyway. And kept using them, even after they stopped using “feminine” anything else.

And so we’re left with our current situation — perpetually anarchic English, with gendered pronouns and anything-goes everything else. Next week we’ll explore the various issues this causes — grammatical and psychological and political and personal — and how, through the ages, people have tried to fix it.

***This detour also means you have more time to write to me ([email protected]) if you have non-binary pronoun stories and/or opinions. Thanks so much to everyone who’s written in so far!

Loving this column!

Super interesting!

The other day I was trying to think of a french gender neutral term that was similar to “partner” in english. But then I realized you’d still have to put ma or mon in front of it.

love love love this article.

This is super interesting and informative! Thanks, Cara!

This series of articles is fabulous.

Thanks for these articles! They are always so well-written and thoroughly researched, all on top of being fascinating to read. Awesome.

Love this series!

I’d be interested to read about the history of implicitly gendered language in English. The word “shrill”, for example, is almost exclusively used to describe women, and “catty” has a similarly derogatory feminine connotation. While a quick look-up of etymology can give a little background on a word’s evolution, I assume gendered coding is tied to history and psychology. I also have a sense some of it has flip-flopped, much like how pink was once a “boy’s color”.

Thanks for this. The English teacher in me appreciates you (and will be incorporating this into my linguistics unit that immediately follows Beowulf :)

oh man what a compliment! thank you!

Ugh, this is the coolest ever. I’m curious to send my mom these links but then I’m terrified about everything else she could read that could be traced back to me…

Brava! What an interesting article.

This is why I love finnish, there is only one word for him/her, “Hän”. So I guess it would be the equivelent to calling everyone “they” here :D (Plus items don’t have genders, hallelujah!)It’s a completely gender-neutral language :)

Quechua is a genderless language (except for a couple of words, like mom/dad), and it is the best. “Yana” is significant other, no matter the gender, for example, and he/she/it are all “pay.”

This column is everything my queer linguistics-major heart desires in life. (Also, ANNE CURZAN IS THE FUCKING BEST and I got to be her student once, just couldn’t resist bragging/singing her praises.)

In my intro linguistics class, the prof was talking about Bantu languages with like 16 grammatical genders, and made some joke about how “our conception of gender is not quite THAT liberal” and I was like “fuck you yes it is, ALL THE GENDERS.”

If anyone conlangs (I’m too lazy to really do it but I think vaguely conlangy thoughts sometimes), I like the idea of a language with optional gender marking on first person forms, and no gender marking on any other persons, the idea being that you can define your own gender or decline to define it, but you can’t define anyone else’s gender.

Yes! As a student-linguist and conlanger, I love that you guys wrote an article on this. I think it’d be really interesting if you wrote one on how grammatical gender influences thought. I know Lera Boroditsky, among others, has done a lot of research here.

ohoho just you wait till next week.

I like to define gender and sex.

Sex to me is chromosomes, i.e xx and xy, in terms of other forms if it has a y is technically male.

Gender is what ever you want to be, a male can be feminine and a female can be masculine, and so on, gender is everything but sex is pretty binary.

Practical ideas , I learned a lot from the details ! Does anyone know if I can get a sample a form copy to work with ?