This post was originally published on November 26, 2014, following the failure to indict Darren Wilson for the murder of Micheal Brown. It was updated to add new pieces on June 2, 2020.

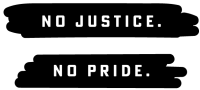

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual, which includes celebrating Pride. This week, Autostraddle is suspending our regular schedule to focus on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. Instead, we’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

This list consists entirely of longform interviews, essays and articles by black people about the experience of being black in the white supremacy of America, police violence, and the U.S. government’s undeclared war on its black citizens. These are mostly essays focused on the situation from a wider lens, rather than reporting on various specific incidents and situations (which I will make another reading list for.)

I wanted this post to center on black voices, so all the authors are Black. However, if you’re gonna read two things by white people, I’d suggest reading The Making of Ferguson, a report by Richard Rothstein for The Economic Policy Institute, which is incredibly thorough as it sets up the historical and cultural forces that made Ferguson such a ripe epicenter for this current conflict. I also found Why It’s Impossible To Indict A Cop very educational.

Please feel free to share your own reading suggestions in the comments with links to where you can find things! Obviously this list isn’t comprehensive and I’m hardly an expert curator, but hopefully there’s something in here that speaks to you.

1964: Martin Luther King Junior – A Candid Conversation With The Nobel Prize-Winning Civil Rights Leader, by Alex Haley for Playboy

“I have been dismayed at the degree to which abysmal ignorance seems to prevail among many state, city and even Federal officials on the whole question of racial justice and injustice. Particularly, I have found that these men seriously—and dangerously—underestimate the explosive mood of the Negro and the gravity of the crisis. Even among those whom I would consider to be both sympathetic and sincerely intellectually committed, there is a lamentable lack of understanding. But this white failure to comprehend the depth and dimension of the Negro problem is far from being peculiar to Government officials. Apart from bigots and backlashers, it seems to be a malady even among those whites who like to regard themselves as “enlightened.””

1966: The Watts, by Bayard Rustin for Commentary Magazine

At a street-corner meeting in Watts when the riots were over, an unemployed youth of about twenty said to me, “We won.” I asked him: “How have you won? Homes have been destroyed, Negroes are lying dead in the streets, the stores from which you buy food and clothes are destroyed, and people are bringing you relief.” His reply was significant: “We won because we made the whole world pay attention to us. The police chief never came here before; the mayor always stayed uptown. We made them come.” Clearly it was no accident that the riots proceeded along an almost direct path to City Hall.

1966: A Report From Occupied Territory, by James Baldwin for The Nation

Now, what I have said about Harlem is true of Chicago, Detroit, Washington, Boston, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and San Francisco—is true of every Northern city with a large Negro population. And the police are simply the hired enemies of this population. They are present to keep the Negro in his place and to protect white business interests, and they have no other function. They are, moreover—even in a country which makes the very grave error of equating ignorance with simplicity—quite stunningly ignorant; and, since they know that they are hated, they are always afraid. One cannot possibly arrive at a more surefire formula for cruelty.

1968: James Baldwin Tells Us All How To Cool It This Summer, in Esquire Magazine

This interview is incredible. And it could’ve happened yesterday, too, is the thing: police brutality, “looting,” declaring a war on a nation within a nation. Everything he says he could have said yesterday and that is really f*cking sad.

If you can shoot Martin [Luther King Jr.], you can shoot all of us. And there’s nothing in your record to indicate you won’t, or anything that would prevent you from doing it. That will be the beginning of the end, if you do, and that knowledge will be all that will hold your hand. Because one no longer believes, you see—I don’t any longer believe, and not many black people in this country can afford to believe— any longer a word you say. I don’t believe in the morality of this people at all. I don’t believe you do the right thing because you think it’s the right thing. I think you may be forced to do it because it will be the expedient thing. Which is good enough.

1969: Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female, by Frances Beal

This racist, chauvinistic and manipulative use of black workers and women, especially black women, has been a severe cancer on the American labor scene. It therefore becomes essential for those who understand the workings of capitalism and imperialism to realize that the exploitation of black people and women works to everyone’s disadvantage and that the liberation of these two groups is a stepping stone to the liberation of all oppressed people in this country and around the world.

1973: To My People, by Assata Shakur

They call us murderers, but we did not murder over two hundred fifty unarmed Black men, women, and children, or wound thousands of others in the riots they provoked during the sixties. The rulers of this country have always considered their property more important than our lives. They call us murderers, but we were not responsible for the twenty-eight brother inmates and nine hostages murdered at attica. They call us murderers, but we did not murder and wound over thirty unarmed Black students at Jackson State—or Southern State, either.

1975: Toni Morrison at Portland State

It’s important, therefore, to know who the real enemy is, and to know the function, the very serious function of racism, which is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining over and over again, your reason for being.

1984: Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference, by Audre Lorde

“Some problems we share as women, some we do not. You [white women] fear your children will grow up to join the patriarchy and testify against you, we fear our children will be dragged from a car and shot down in the street, and you will turn your backs on the reasons they are dying.”

1995: Thirteen Ways Of Looking At A Black Man, by Henry Louis Gates

…the Simpson trial spurs us to question everything except the way that the discourse of crime and punishment has enveloped, and suffocated, the analysis of race and poverty in this country. For the debate over the rights and wrongs of the Simpson verdict has meshed all too well with the manner in which we have long talked about race and social justice. The defendant may be free, but we remain captive to a binary discourse of accusation and counter-accusation, of grievance and counter-grievance, of victims and victimizers.

1996: Killing Rage, by bell hooks

“It was these sequences of racialized incidents involving black women that intensified my rage against the white man sitting next to me. I felt a “killing rage.” I wanted to stab him softly, to shoot him with the gun I wished I had in my purse. And as I watched his pain, I would say to him tenderly “racism hurts.” With no outlet, my rage turned to overwhelming grief and I began to weep, covering my face with my hands. All around me everyone acted as though they could not see me, as though I were invisible, with one exception. The white man seated next to me watched suspiciously whenever I reached for my purse. As though I were the black nightmare that haunted his dreams, he seemed to be waiting for me to strike, to be the fulfillment of his racist imagination.”

2012: A Place Where We Are Everything, by Roxane Gay for The Rumpus

Unchanged:

When white people got on my nerves, or started to force their racial intolerance on me, I thought, “I come from a place where we are everything.” I realize now what a privilege it has been to have that. What I want for my children and your children is to have a place where they can feel like they are everything and still be surrounded by people who are different. That should be an inalienable right, too. That is not too much to want.

2012: How To Kill Yourself and Others in America: A Remembrance, by Kiese Laymon for Gawker

Mama’s antidote to being born a black boy on parole in Central Mississippi is not for us to seek freedom; it’s to insist on excellence at all times. Mama takes it personal when she realizes that I realize she is wrong. There ain’t no antidote to life, I tell her. How free can you be if you really accept that white folks are the traffic cops of your life? Mama tells me that she is not talking about freedom. She says that she is talking about survival.

2013: A Clear Presence, by Aisha Sabati Sloan for Guernica

Rodney King was swimming on the first day he ever heard the word n*gger. His small self popped out of the water only to be pelted by a fast-passing stone. It was the first time he realized that he wasn’t just a kid; he was a black kid. Despite the life he would live thereafter, King writes that it was “the saddest day in creation for me.” He wishes he could “find a way of forever removing that day from every black child’s life.”

2013: De Origine Actibusque Aequationis, by Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah for The Los Angeles Review of Books

Words like Jeantel’s — often expressed in far-out forms like graffiti and slang — trace the sense of feeling X-filed; they are the ways to acknowledge life in the bush of ghosts, and give names and sounds to the consciousness of radical world-building that the descendants of the African Diaspora have engaged in all around the world. This is the tradition Rachel Jeantel was practicing up on the stand: the art of being young, black, and incomprehensible.

2013: Some Thoughts On Mercy, by Ross Gay for The Sun Magazine

Isn’t it, for them, for us, a gargantuan task not to imagine that everyone is imagining us as criminal? A nearly impossible task? What a waste, a corruption, of the imagination. Time and again we think the worst of anyone perceiving us: walking through the antique shop; standing in front of the lecture hall; entering the bank; considering whether or not to go camping someplace or another; driving to the hardware store; being pulled over by the police. Or, for the black and brown kids in New York City, simply walking down the street every day of their lives. The imagination, rather than being cultivated for connection or friendship or love, is employed simply for some crude version of survival. This corruption of the imagination afflicts all of us: we’re all violated by it. I certainly know white people who worry, Does he think I think what he thinks I think? And in this way, moments of potential connection are fraught with suspicion and all that comes with it: fear, anger, paralysis, disappointment, despair. We all think the worst of each other and ourselves, and become our worst selves.

2013: The Year in Racial Amnesia, by Cord Jefferson for Gawker

All those who would look back to the “charms” of Olde America seem unaware that those days are not so far gone. The United States has improved such that we no longer have mobs that gather to watch a lynched body the way they might watch a fish struggle on a line. But we’re lying to ourselves if we think Florida police arresting a black man dozens of times simply for going to work isn’t an act underpinned by the old notion that some people’s rights are worth less than the rights of others.

2014: The Case for Reparations, by Ta-Nehisi Coates for The Atlantic

This article should be required reading for all American citizens.

Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.

2014: Fear and Aggression in Florida, by Elias Rodriques for n+1

Fear isn’t only a reaction, and Stand Your Ground, like its predecessor the Castle Doctrine, made it rational to err on the side of aggression. This was especially true for my black friends, who encountered hostility the way other people encounter the sun. Worried about being hurt or killed, we endlessly prepared for defense. As teenagers, we bragged about our strength, about how nobody could hurt us, how we would win any fight. Even when we didn’t believe ourselves, we sometimes fooled each other.

2014: Blackness As The Second Person, Meara Sharma Interviews Claudia Rankine for Guernica

I felt like, holy shit, I am walking around, and all of these people, white people, are okay with my black body being beaten and kicked, even when they’re seeing the violence actually happen and don’t have to rely on hearsay. That the black body is perceived as dangerous, even when it’s on the ground, in a fetal position, with men surrounding it, kicking it. I don’t think I understood or felt as vulnerable ever before.

2014: Black Girl Walking, by Hope Wabuke for Gawker

Really, though, I wonder what I as a black woman can do, in America in 2013, to be seen not as the target of raced and gendered violence, but as a black woman worthy of respect, decency, and protection because of my race and gender, not in spite of my race and gender. What will it take for black women like me, like Marissa Alexander, and like Renisha McBride, to ever be treated and defended by the citizens of our country as innocent?

2014: Let’s Be Real, by Wesley Morris for Grantland

There are far more attempts to understand police on television and in the movies than there are attempts to empathize with black men, whether or not those men happen to be cops.

2014: On Ferguson Protests, the Destruction of Things, and What Violence Really Is (And Isn’t), by Mia McKenzie for Black Girl Dangerous

On why it is that killing black people doesn’t get talked about as violence but destroying white people’s things does.

2014: I Am Utterly Undone, by Dr. Brittany Cooper for Salon

Humans can only be sucker punched for so long. Humans can only have the life choked out of us for so long. Humans can only be kicked in the stomach while your foot is on our neck for so long. Humans can only be bullied for so long. One day we stagger to our feet, and you see reflected back to you the results of your own unresolved monstrousness.

2015: The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning, by Claudia Rankine for The New York Times June 2

The Black Lives Matter movement can be read as an attempt to keep mourning an open dynamic in our culture because black lives exist in a state of precariousness. Mourning then bears both the vulnerability inherent in black lives and the instability regarding a future for those lives. Unlike earlier black-power movements that tried to fight or segregate for self-preservation, Black Lives Matter aligns with the dead, continues the mourning and refuses the forgetting in front of all of us.

2015: How Black Reporters Report on Black Death, by Gene Demby

As calls for newsroom diversity get louder and louder — and rightly so — we might do well to consider what it means that there’s an emerging, highly valued professional class of black reporters at boldface publications reporting on the shortchanging of black life in this country. They’re investigating police killings and segregated schools and racist housing policies and ballooning petty fines while their loved ones, or people who look like their loved ones, are out there living those stories. What it means — for the reporting we do, for the brands we represent, and for our own mental health — that we don’t stop being black people when we’re working as black reporters. That we quite literally have skin in the game.

2015: The Unauthorized Biography of a Black Cop, by Chris Johnson for Gawker

As the years go by, more stories are retired, suppressed, or if conjured up again from the dirt of remembrance, remixed not so much for glory and amusement but as explanations, apologies, confessions, immolation—the atonement a poor black youth conscripted, a retired mercenary vampire that drained democracy of its hemoglobin, who walloped and handcuffed on behalf of the white supremacist capitalist oligarchs who profited from his neck-breaking labor.

2015: A Love Note o Our Folks, by Alicia Garza for n+1

There was a lot of stuff happening. We instantly realized that this was a struggle being led and directed by young people, and people were trying to figure out how to respond and how to relate to that. Young people were really fighting for their space, and really saying, you know, “We’re getting killed. And we’re not going to go home, we’re not going to be quiet, we’re not going to be nice, we’re not going to tone it down. This stuff is going to stop today.”

2015: In Conversation: DeRay Mckesson for New York Magazine

Students are protesting in order to create spaces that promote dialogue and rich conversation. They are protesting to bring the First Amendment to campus in ways that actually speak to and acknowledge the black experience. I think that what’s challenging for some people in the current context is that we are witnessing the necessary uneasiness of intellectual discussion happening in real-time. But communities are better when different viewpoints are put forward that allow for deep discussion. Tension isn’t necessarily negative. The tension is the work.

2016: Black Lives and The Police, by Darryl Pinckney for The New York Review of Books

Jurisdictions like Ferguson, Missouri, know who their trouble officers are. They accumulate histories of racial incident. They arrive as known quantities. It’s time to make it harder to become a police officer. The ones ill-suited for the job are burdens for the ones who are good at it. The videos of police killings also help explain those doubtful cases for which there are no accidental witnesses. The footage shows not only blood lust, state-sanctioned racism, or the culture of the lone gunman in many a police head, but also incompetence.

2016: Making Black Lives Matter in the Mall of America, by Erik Forman for The New Inquiry

The shutdown of the Mall of America pointed to a potential way to take the movement forward. The mall is not only a space of consumption but also a space of production animated by the labor of over 10,000 low-wage service workers, disproportionately black in the majority-white state of Minnesota. The radical labor tradition has long sought to organize at the intersection of black power and workers power. Black labor exploited by white capitalists has been the starting point for a current of resistance stretching back to the earliest days of colonization.

2017: Respectability Will Not Save Us, by Carol Anderson for LitHub, August 2017

The implications were clear: they were not going to get the status of grieving parents, their pain would not be acknowledged as legitimate, and they would be stripped of even the right to mourn their dead child. They were unworthy. The prosecutor made that clear when he suggested that the reason the parents insisted upon an indictment and a trial had nothing to do with justice for their murdered son but was, instead, for financial reasons.

2019: America Wasn’t a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made it One, by Nikole Hannah-Jones for The New York Times

“…it would be historically inaccurate to reduce the contributions of black people to the vast material wealth created by our bondage. Black Americans have also been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom. More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: It is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy.”

This is so, so important, and those images are chilling. Thank you, Riese.

I’m going to try to make it a point to set aside time this weekend and read through these.

Thank you for doing this Riese.

This is exactly the type of reading I wanted for my long weekend and I still need to process my Monday feelings. Thanks Riese!

yes, thank you riese.

i’ve been digging through what i’ve already saved to instapaper, trusting there were more things in there to help me figure this out. this list is exactly what i was looking for. the things i’ve read on this list stick with me, and i am eager to plow through the rest.

Thank you. I’m forwarding this to everybody.

Thank You.

I wish I wasn’t at work so I wouldn’t have to hide my tears at reading these.

This is exactly the resource I need right now. Much more effective that fuming silently and smash-typing passive-aggressive FB status updates. Thank you for putting this list together.

Finally getting to this and I’m so glad. I want to send this to every uninformed person who has asked me why #Ferguson matters.

Thank you for this list.