June is LGBT Pride Month, so we’re celebrating all of our pride by feeding babies to lions! Just kidding, we’re talking about lesbian history, loosely defined as anything that happened in the 20th century or earlier, ’cause shit changes fast in these parts. We’re calling it The Way We Were, and we think you’re gonna like it. For a full index of all “The Way We Were” posts, click that graphic to the right there.

Previously:

1. Call For Submissions, by The Editors

2. Portraits of Lesbian Writers, 1987-1989, by Riese

3. The Way We Were Spotlight: Vita Sackville-West, by Sawyer

4. The Unaccountable Life of Charlie Brown, by Jemima

5. Read a F*cking Book: “Odd Girls & Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in 20th-Century America”, by Riese

6. Before “The L Word,” There Was Lesbian Pulp Fiction, by Brittani

7. 20 Lesbian Slang Terms You’ve Never Heard Before, by Riese

8. Grrls Grrls Grrls: What I Learned From Riot, by Katrina

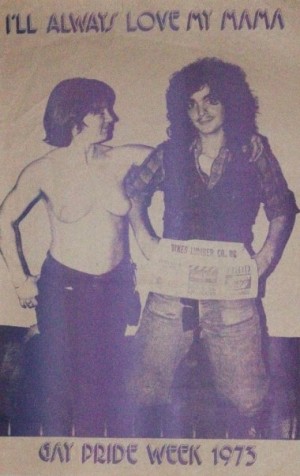

9. In 1973, Pamela Learned That Posing in Drag With a Topless Woman Is Forever, by Gabrielle

![]()

It was March 8, 1973, a memorable day for Pamela: she had just quit smoking for the first time. (She would quit again and again until her actual last cigarette on June 3, 1990). The other events of that day did not, at the time, seem particularly noteworthy.

Pamela was living in New York City, on Christopher Street right at Sheridan Square. She was a proudly out lesbian in a time and at a place where gay visibility was on the rise: four years after the Stonewall Riots, coming out had become a political strategy of the movement. There was an infectious queer fierceness in the air. ‘Homosexuality’ had just been removed from the DSM as a pathological disorder.

Pamela had been earning extra money for several years giving alternative lifestyle haircuts to dykes around town, a pastime that remains a special talent of many lesbians to this day. Pamela had created a barber drag persona for herself by drawing on a mustache and carrying haircutting tools in a Dykes Lumber apron.

On March 8, Pamela was giving a haircut in her friend Trixie’s loft at 810 Broadway, a building in Greenwich Village that’s now super fancy. She was cutting the hair of a lesbian named Ayn (pronounced Ian), who was Trixie’s girlfriend Peggy’s friend, in town from Boston.

Oftentimes, Pamela’s clients would take their shirts off during their haircuts (for clean up purposes, duh). And sometimes, Pamela could get them to pose for her. So, as was customary, Ayn had taken her shirt off for the haircut. But rather than Pamela taking a photo of the haircut afterwards, Trixie snapped a picture of Pamela and Ayn together — Ayn, still topless, and Pamela, still in barber drag. It didn’t seem like a big deal. Just a bunch of lesbians, cutting hair, taking shirts off, taking pictures. The usual.

Nowadays, hopefully we all know that if you’re going to be in a picture with naked boobs you should probably a) keep track of it and/or b) not put it on the internet, unless you just aren’t trying to get a day job where they look into things like that – in that case, you do you!

Before the internet, information was disseminated using “printing presses.” Unbeknownst to Pamela, Trixie gave the photo to an underground community printing press run by a lesbian named Mercury Volt, who Pamela very specifically recalls as being a Gemini. (Mercury Volt also printed the questionnaires for the first Hite Report, a very famous study on female sexuality, which was at the time an underground endeavor due to a lack of funding.)

Three and a half months later, it was Gay Pride Week – one of the first of its kind. Pamela’s father came to the Village to take her out to dinner. They were close; she had come out to him at 17. After dinner they went for a walk around the gayborhood. That’s when Pamela saw it: plastered literally all over the place, on every wall and phone booth, was her own face staring back at her.

via The Lesbian Herstory Archives

The photo of Ayn and Pamela taken by Trixie on March 8 had been blown up into a Gay Pride Week ‘73 poster that was captioned, “I’LL ALWAYS LOVE MY MAMA.” It’s unclear where that caption came from – you never know with Geminis.

Maybe it was because of the barber drag, or maybe it’s because parents see us as they want to – either way, Pamela’s dad didn’t notice his daughter in the posters. He also somehow didn’t notice Pamela’s total panic as they passed phone booth after phone booth covered with her mustached face and Ayn’s breasts. And that caption! Pamela had called other women “sister” from time to time, but she had never, ever called another woman Mama. She found the words humiliating, and was upset that Trixie hadn’t asked her permission.

But aside from the caption and the initial shock, Pamela didn’t really mind so much. To be featured in an advertisement for Gay Pride that celebrates lesbian life using this unrehearsed, un-self-consciously organic portrayal of dykes is actually pretty cool.

More than twenty years later, in the late 1990s, Pamela was at a party that filmmaker Joyce Warshow held for her friend, Blue Lunden. Blue was a working class butch dyke, and the muse for Joyce’s most well-known film, a documentary called Some Ground to Stand On. Joyce had been inspired to make the film in part because of the serious lack of documentation of working class butch experiences. Pamela had done a bit of post-production work on the film and so had seen it several times. She was fond of Blue from afar.

Pamela and Blue hadn’t met before Joyce’s party, where Blue immediately recognized Pamela’s face from the Gay Pride ’73 poster that had been hanging on her wall for the past 20 years. Pamela was flattered, and found it incredible that Blue had identified her after all those years and without the mustache on – even when her own father hadn’t.

And perhaps that speaks to the special secret language of lesbian visibility that has connected us to one another throughout time. Our ability to be known to each other but not to others is what created community in times when no one was yet dreaming of mainstream rights like marriage equality. But this was a time when the importance of being seen, not just to one another but to the rest of the world, had leapt to the forefront of the movement. And it was a radical visibility proclaiming that pride can and should be derived from the basic realities of queer lives – like some dykes getting together to cut hair. The rest of the world, like Pamela’s father, had only just started to take notice.

Note: The poster found its way to the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and I came across it while archiving the graphics collection in August of 2009. I left it out on the conference table, and it was noticed by another coordinator who immediately recognized Pamela as her first roommate when she moved to New York City. Parts of this story are based on their subsequent email correspondence, with permission.

I too am confused by the caption, but intrigued by the apron. Do they still sell those?

Also, Pamela sounds awesome and this is a great article.

(See? I am completely capable of writing comments that actually pertain to the topic at hand. They’re just…not what immediately come to mind.)

Visibility is a funny thing. When I started wearing guys’ button-downs and cut my hair short enough that I could no longer rock a ponytail, only my parents and my older relatives caught on to the relatively obvious gay coding going on. Everyone my age who I wasn’t out to yet thought I was just becoming a hipster.

I liked this. Like, really liked this. A lot.

me too!

Ok this article is super awesome and now has me thinking really hard about queer visibility and I’m working up theses for a research project. Also, I just gotta say, as a library nerd, it makes me super happy that you just happened across this picture in an archive and followed up on the story. This is the kind of thing I want to do!

This is really interesting to me on a personal level as well. There are some days (well, just about every day) when I look at myself in the mirror and think, “Wow, I look REALLY gay today.” But my parents, who I haven’t come out to yet, don’t seem to notice. And I seriously wonder if it’s because they really just don’t read my appearance as gay or if they do and just aren’t going to be the first to mention it.

Ok time to research! ::cracks books::

I know! My friends were all totally shocked when I came out and now (good-naturedly) poke fun at my “lesbian wardrobe” and I’m like “… I haven’t bought new clothes since high school…”

great article! btw, the caption comes from a song in 1973 by the intruders.

and an awesome song too! I grew up loving Motown and TSOP, not to mention my mom, so it’s one of my original favorite jams.

check it out http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3GjxlguPYo0

although now I find the line “you only get one” funny because someday my kids are totally gonna have two

Really love this!

ohmygod this is great! also: geminis are the kryptonite to my sagittarius heart. sigh.

Awesome article!

Dykes Lumber is an actual commercial enterprise that has been operating out of a warehouse on West 44th Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues since 1912. I just had to check the place out the first time my impressionable baby dyke eyes saw their large yellow “DYKES” sign smack dab in the middle of then-infamous Times Square. (That was back in the 1970’s.) Sadly, Dykes Lumber no longer sells the carpenter’s apron Pamela is fashioning in the 1973 Pride poster, but don’t despair: $16 will get you a Dykes Lumber t-shirt (they are available in classic black, stone-cold blue and fashionable pink . . . sounds like they know who their market is). Visit http://www.dykeslumber.com or call 888-42DYKES for more info.