Header by Rory Midhani

Header by Rory Midhani

I spent this past weekend playing and replaying The Beginner’s Guide, an experimental narrative-based game released by The Stanley Parable’s Davey Wreden on Thursday. It’s described (vaguely, but accurately) on Steam as “the story of a person struggling to deal with something they do not understand.” I would describe it (also vaguely, also accurately) as sort of similar to the book House of Leaves, or the film Adaptation. If you find either of those things interesting, go and get this game immediately, because it’s brilliant. It costs under $10, and start-to-finish, it takes only an hour and a half to play all the way through. Truly.

Here’s the trailer:

In the intro chapter — narrated in voiceover by Davey Wredon himself, as is the rest of the game — we’re told that this game will take us through a series of games made by a friend of Davey’s named Coda.

“Coda starts making these games, and he never releases any of them. He doesn’t put them onto the internet, he just makes them and then immediately abandons them, and they sit on his computer forever. And I think he really understood this image of himself as a recluse. At one point he jokingly renamed his computer’s recycling bin to “Important Games folder.” So, you know, this was just how he worked. He tended to crank them out one after the other without even really pausing to try to understand what he had just made, until suddenly one day he just stopped. In 2011, he made his last game and then he hasn’t made another one since. And that’s why I’ve taken the opportunity to gather all of his work together, is because I find his games powerful and interesting, and I’d like this collection to reach him, to maybe encourage him to start creating again. And if the people like you who play this also happen to find his work interesting, then I’m sure it’ll send that much stronger of a message of encouragement to Coda.”

Rereading this introduction now fills me simultaneously with awe as a writer, and rage as a human being. And that’s about all I can say without getting into specifics.

I’m going to talk about the game in depth now, and I want you to know: what I’m going to say will definitely ruin your experience with this game if you have not played it yet and think you might like to. I highly recommend that you play it first and then come back. Major spoilers ahead.

Thank you Weaver for telling me about this game!

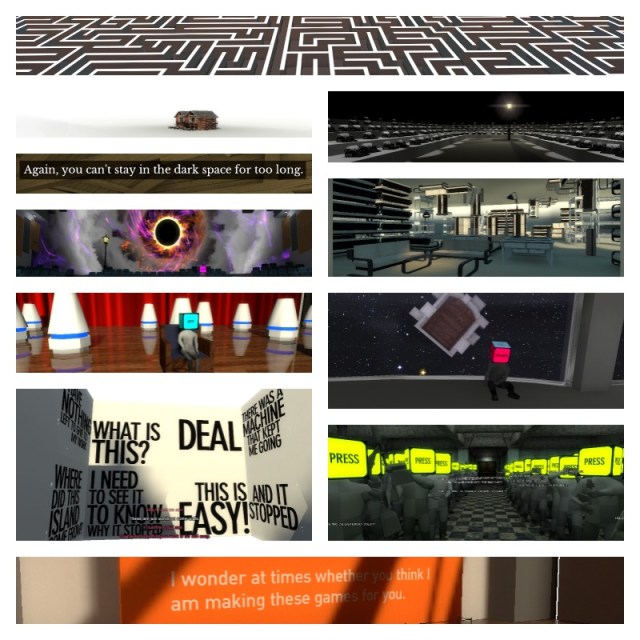

Okay, so hopefully you’ve played through the game by now. If not, here’s how it goes down: after the introduction, there are 16 chapters and an epilogue. Davey takes us through the games in chronological order of creation, and we watch as the game developer (apparently) evolves over time. They start by making a de_dust-y Counter Strike level, then a few tiny original games that experiment with game mechanics and architecture, playing with the idea of what’s seen vs. unseen.

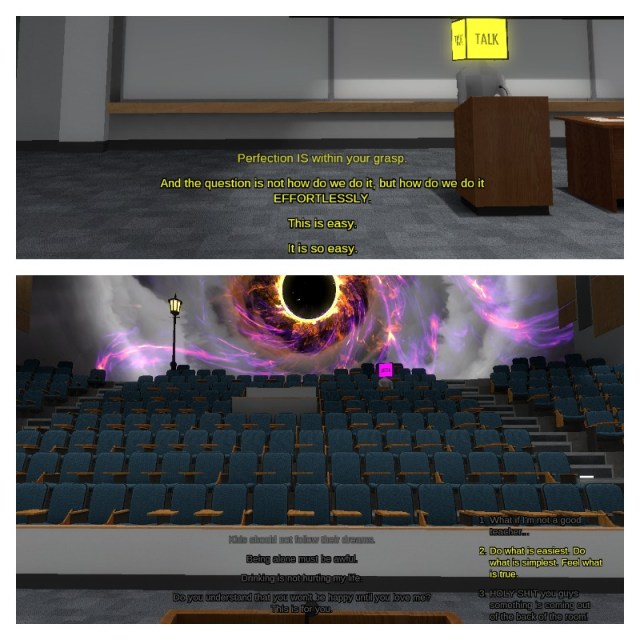

Images from the introduction and first five chapters of The Beginner’s Guide.

As we progress through the collection, Davey’s narration gleefully shares his interpretation of the deeper meaning behind every gamemaking choice. The explanations are clever, and the major symbols are succinct and clear. Puzzle doors equal momentary reflection, closure; lampposts equal goalposts, destinations; mazes equal… well, there doesn’t seem to be any point to those, actually. And when Davey finds elements that do not provide value, he skips us past them — sometimes giving us a choice, and sometimes not. But the assistance is increasingly necessary, because as the games progress, they become increasingly unplayable. They get weird and dark, frequently infused with this sense of helplessness and despair. They play with themes of imprisonment, lack of self-determination, and always being watched. Davey describes them using words like “cold,” “distant,” and “scary,” and during my first play through, I wholeheartedly agreed when Davey expressed concern over his friend’s apparent depression and reclusiveness.

Gradually, then suddenly, this illusion is burst.

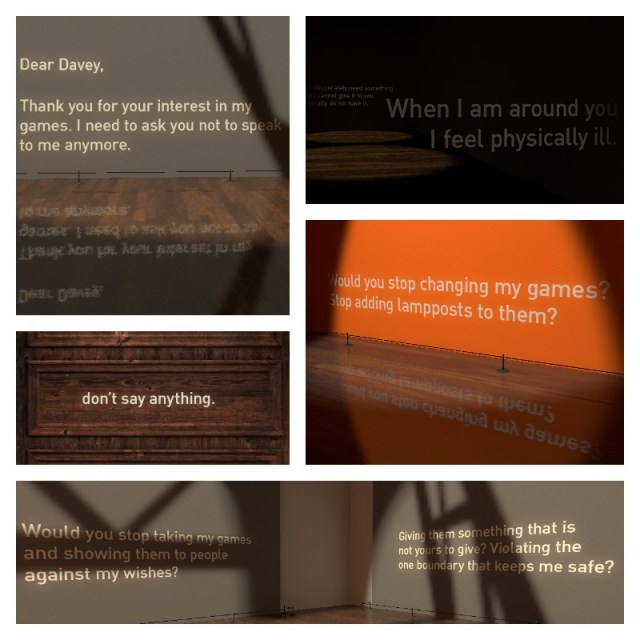

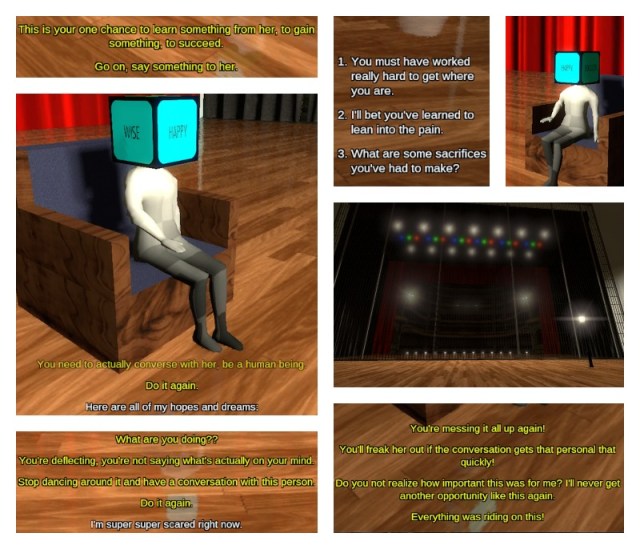

Images from the remaining chapters and epilogue.

On the walls of the final chapter (16: “Tower”), we find that Coda has written a series of messages for Davey. “Dear Davey,” it begins. “Thank you for your interest in my games. I need to ask you not to speak to me anymore.” As the messages progress, the truth of the situation becomes clear: Davey was not Coda’s friend. In fact, Davey had repeatedly violated Coda’s boundaries, and his actions made Coda feel unsafe and, at times, physically ill.

Honestly, it’s shocking. I actually gasped out loud when I reached the following note from Coda: “Would you stop changing my games? Stop adding lampposts to them?” Because: What. The. Fuck. What the fuck! Are you serious?!

(Some of) the writing on the walls.

Up until this point, we’ve seen everything through the lens of Davey’s interpretation. He introduces the first lamppost in chapter seven (“Down,” according to Davey’s title; “The Great and Lovely Descent,” according to Coda’s title), saying:

Okay, I can’t tell you quite why but for some reason Coda fixates on this lamppost. It’s going to appear at the end of every single one of his games from here on out. … Because now he wants something to hold onto. He wants a reference point. He wants the work to be leading to something. He wants a destination! Which is what this lamppost is, it’s a destination. We’re gonna see it in the work as well, his games are going to become a lot more cohesive, a lot more fully developed, with more of a clear idea behind them. And as we go, that idea will get clearer and clearer.

Based on this, it looks like Davey planted those lampposts with the express intent of inserting new meaning to the games, then deliberately hid the fact that he had done this. For me, that’s a huge breach of trust; it completely eradicates my confidence in Davey as our narrator. Because if he was the one responsible for those lampposts, what else in here did he make up? What other aspects of gameplay did he change, and how much?

For example, we know Davey that changed the prison door because he tells us so directly. But now I feel leery about everything. Like, what about the bathroom door? Did Davey modify it in reference to his commentary about accessibility? None of the other doors in that area open.

When I really stop and think about it, I’m not sure whether I believe that Davey has met Coda in person. I question whether he’s even using the correct pronouns! Because ignoring Davey’s narration, the text of the game itself hints to me that it was created by a woman developer. (Or rather, the idea of a woman developer. Just to be clear, I don’t think that Coda is real; if I did, I wouldn’t write this review. One of the main points of the game is that you can’t and shouldn’t pick apart creators based on their art. I agree with that completely. However, Coda is a creation, not a creator. So game on.)

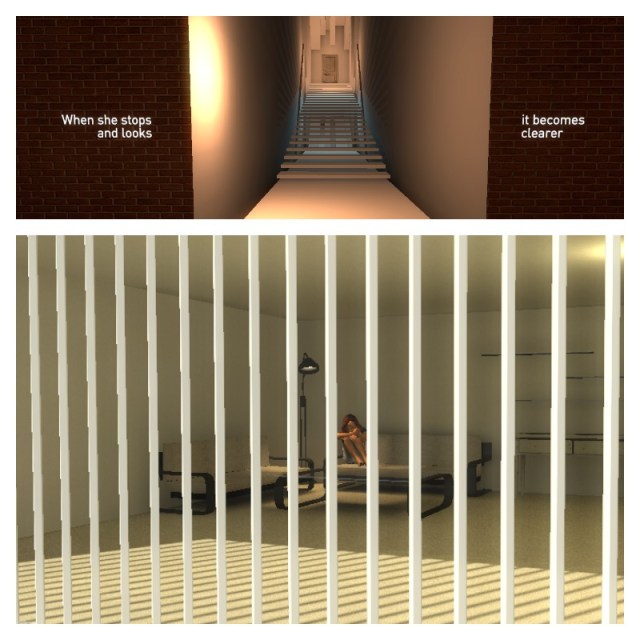

Because I am who I am, I was delighted to see evidence of a strong female presence strung throughout these games. In the first chapter (“Whisper”), the voice within the game that asks us to stop the beam is female. In the next chapter (“Backwards”), the writing on the wall uses female pronouns: the past is behind her; she must find the strength to confront the future. In chapter 15 (“Machine”), the guard greets us: “Ma’am!” And the only human figure shown throughout the entire game is in chapter 14, “Island,” where we glimpse a female figure behind bars.

Not pictured: the lamppost directly to the left of this prison cell. Davey whisks us away before we’re able to get any closer than this.

For me, the most relatable parts of the broader game were actually scenarios that made me think of gendered experiences I’ve had in the professional world. I don’t think they’re necessarily specific to engineering or even STEM, but that’s how I connected with them. For example, a common theme throughout many of the later chapters is imposter syndrome. In chapter 11 (“Lecture”), we are first positioned as members of an audience, watching a lecturer explain how to achieve effortless perfection. Halfway through, the perspective shifts and we become the lecturer. We are given the choice to continue reciting from the golden script (ex: “Do what is simplest. Feel what is true.”), or voice our insecurities (ex: “What if I’m not a good teacher…”) or speak other truths (ex: concern about the swirling vortex at the back of the classroom).

Oh, girl.

In the next chapter (12: “Theater”), we’re dropped into a gathering of professionals and instructed to engage a woman as a mentor. The interaction is described as extremely important, our “one chance” to gain success. Yet no matter how much we agonize over selecting the right string of words, there’s nothing we can say within the interaction to make the desired connection. It simply isn’t going to happen. We anxiously berate ourselves for the failure, then retreat.

Why is this one woman so important to connect with? Aren’t there any others out there that could possibly help us?

By and large, these are not happy games.

There is this one, however, about finding comfort in household tidying. In chapter 10 (“House”), warm, unobtrusive music tinkles softly in the background as you perform light housekeeping tasks on a loop and get to know to know your companion. It’s very pleasant! Davey describes this game as coming out of a period where Coda was “grossly happy.” Obviously this doesn’t mean that the developer had to be a woman; that’s insulting. But I do think it plays into the pattern of how these games approach gender, casually setting women and women’s perspectives as “default” within these worlds.

In Oh No! Video Games’s excellent podcast on Beginner’s Guide, feminist video game critic Laura Kate Dale describes the theme of this game as “continued work as a distraction to quiet the soul.”

“I’m glad he made this. I’m glad he found some peace. But of course, it can’t last. The music stops, your companion is gone, it’s time to leave!” Davey says in voiceover at the end of this chapter. And of course, the music does stop and your companion does leave. Our ever-analytical narrator opines, “You can’t stay in the dark space for too long. You just can’t. You have to keep moving, it’s how you stay alive. Which is the whole point of the puzzle, right? That sooner or later you have to pick up and move? I really thought that was the point of it.”

In the final chapter, however, Davey tells another story:

To be fair, it’s not like this [final chapter] is the first game that’s needed some modification to be playable. Like the housekeeping game. You know, that one used to actually loop the cleaning chores and you just cleaned a house forever. I had to cut it off so that you could exit the house and the game would actually end. But that game had an idea that it was actually trying to communicate.

Which… no? Davey had an idea he was trying to communicate, and he twisted the game to make it fit those parameters. The original game sounds like something different entirely. It reminds me of the countless hours my best friend and I spent playing Harvest Moon 64, completing farmwork and trying to figure out which conversation trees would make the female NPCs reveal their secrets and fall in love with us. That was a game about domestic contentment, I think, and long-term relationship building. So was Coda’s original housekeeping game. It feels really wrong to me that Davey erased that and replaced it with what amounts to the opposite message.

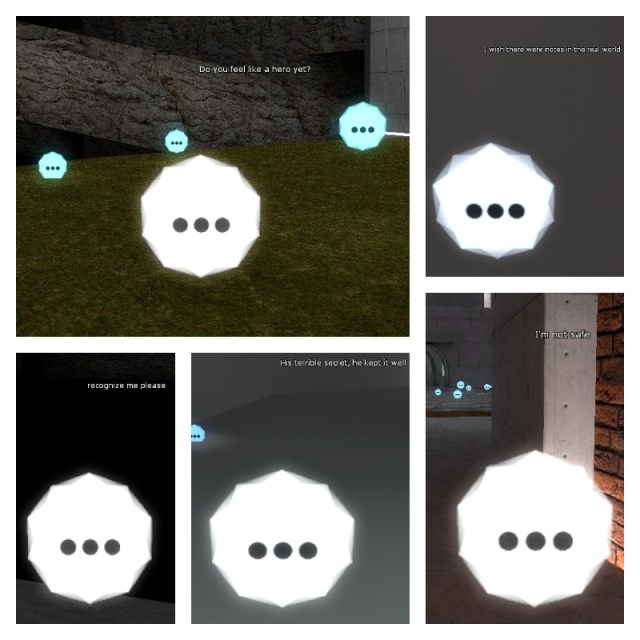

Text from some of the notes strewn throughout the game in chapter 12: “Do you feel like a hero yet?” “I wish there were notes in the real world” “I’m not safe” “His terrible secret, he kept it well” “recognize me please”

According to Davey’s narration, he met Coda at a weekend gaming jam in Sacramento. In chapter 12 (“Notes”), Davey tells us, “I saw him working on this very level, and it was just so different from anything that anyone else was doing. So right away I was like, I have to be friends with this person. In retrospect, I think I was probably a bit too pushy? Trying to get his attention? Uh, I was overenthusiastic. But he was very gracious about it and very patient with me. And I cooled off eventually.”

Now, I know the feeling doesn’t really come across in written text, but there’s something about the tone of Davey’s voice and the pauses in his cadence on the audio track that really get to me. To my ears, it sounds like the creepy dude at the bar who keeps pestering a girl until he gets slapped, then sheepishly returns to his friends and selectively glosses over the details as he explains what went down. Maybe Coda’s gender is a glossed over detail. Or, again, maybe they’ve never met in person at all! We really don’t have enough information to say.

Anyway, shortly after relating the circumstances of their meeting to us, Davey returns to the game at hand, nonchalantly advising, “Oh, feel free to skip over any of these notes [left by Coda] if they’re not doing anything for you. Nothing extra is gonna happen if you read all of them.” I find this very odd! Because moments later, he’s telling us:

It’s ironic, isn’t it, that in playing this game and seeing how alone Coda often felt that we get to know him better, and actually kind of connect with him. I have to be honest with you, this idea is really seductive to me! That I could just play someone’s game and see the voices in their head and get to know them better and have to do less of the messy in-person socializing. I could just get to know you through your work. I think this is why I always liked Coda’s games so much, is because it felt like they let me have that connection. I felt as though he was inviting me personally into his world. And then I feel less lonely too.

While Davey has access to the full, original material, our access is limited and filtered through Davey. At a couple points in the game, we’re shown large areas full of unread messages. Yet when we try to jump or cross to read them, an invisible boundary stops us. One area in particular has a message perched near the edge of a ledge saying, “Take my hand, let’s jump together.” It seems to invite us to cross to the other side and read the unread messages; yet when we try to, we cannot. Did Coda do that? Or did Davey?

At another point, we are shown a door with notes in front that say things like, “Makes game. Includes door. Cannot open door. Thanks.” And indeed, the door is unopenable. Yet in later levels, Davey has no problem modifying the game to open other shut doors for us. Why not here too? What is it that drives Davey’s decisionmaking when it comes to respecting or violating the boundaries that Coda has set? Is it based on narrative cohesiveness? Programming convenience? A moral code?

Orbs appear light blue until you open them. They’re white while you’re reading them, and then they fade to grey when you’re done.

I suspect the answer has much less to do with how Davey views Coda, and much more to do with how Davey views himself.

Feminist video game critic Carolyn Petit wrote of The Beginner’s Guide,

If a game is designed to give players a particular sense of ownership, some players will inevitably feel like the world of the game should heed their every desire, at least until the culture surrounding games communicates to (mostly straight white male) players that they shouldn’t expect to always get their way.

Exactly. To me, The Beginner’s Guide game is about a man (poorly) coming to terms with his hugely overinflated sense of entitlement. It is fascinating and horrifying to watch, and doubly so to play.

When I mentioned at the beginning of this article that the introduction fills me with rage, it’s because the violation that took place feels extremely personal. Narrator Davey dragged me across the line with him, and I had no real choice in the matter. I wasn’t given enough information to know what I was participating in. I’d like to think that if I had, I wouldn’t have agreed to it. Personal satisfaction of curiosity is never an acceptable excuse for breach of consent.

I think I empathize with Coda because I know what it’s like to have my personal boundaries be disrespected. I’m familiar with the idea that privacy is a privilege granted to members of the “default” group (straight, monosexual, monoracial, white, neurotypical, cis male). Anyone who falls outside of those categories is subject to invasive scrutiny. The further away from “default” you are, the less you are treated like a human being.

The machine. It calls itself Coda.

I think the brilliance of this game that it forces us as players to confront our own behavior. What are we willing to do to get our way? How critically do we think before accepting other people’s views as our own? What role do we play in dehumanizing others, and in what ways do we abandon or sacrifice our own humanity?

I would love to hear all of your thoughts on this.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.

This is a brilliant review, Laura! Truly, one of the best video game reviews I’ve ever read. I played this last night and found the experience chilling. Now I feel that doubly.

Blushing. Thank you.

I played this recently with a friend (we just kinda switched off and watched one another play) and we both viewed Coda as a trans girl. I know that’s not necessarily the view expressed here, but I’m really happy regardless that you covered this game!

Oh, that’s interesting! I could see that.

My impulse was to jump straight to “Davey is lying and has also made incorrect assumptions,” but you know, maybe that’s just my misandry speaking. :p

That’s how I read it as well, I wondered if anyone thought the same. I thought the prison games especially alluded to that.

Which honestly makes Daveys changes so he gets to ‘solve the problems’ and be the hero of them, and his assumption that the games are about his experience so much more frustrating because it felt like a real reflection of straight male gamers response to everything.

Fascinating game. ‘Stop adding light posts’ was like a punch in the gut and made me stop everything for a few seconds.

OMG ME TOO

I was so convinced Davey was going to return at some point and talk about Coda’s gender transition or something, or some later game would address it directly.

It got way more chilling than I expected but our reads still work in this context, especially when you consider the idea of people misgendering/misrepresenting another person to feel better about themselves.

I keep thinking about this.

Do you remember that thing that happened with Dr. V and that journalist from Grantland? This reminds me of that, especially in the way that Davey is determined to depict a ‘troubled genius’ to the public and will. not. stop. digging.

“an experimental narrative-based game released by The Stanley Parable’s Davey Wreden on Thursday.”

Aaaand that’s all I need to know; it’s immediately on my wishlist. Definitely following your advice to come back to this article once I’ve actually played the game, but thank you for bringing it to my attention!

Yes!! I’m glad.

OMG this game.

Have you played the Stanley Parable?

I played this game because of how much I respected SP.

I just bought it! And I’m planning to play it ASAP.

You know the most annoying thing about that ending?

I really related to that line about not staying in the dark space forever. That you have to keep moving. Because “keep on moving” is pretty much how I get through my dark spaces. It’s often instinctual; people ask me how the hell do I manage to do fifty zillion things at once and I have no answer beyond “I just do”. It’s what gets me out of bed, it’s what keeps me alive.

And now that asshole has to RUIN the sentiment by jamming it into a game that never intended for that message to happen.

FUCK YOU!

(well, not you Laura, but y’know)

<3

That’s so frustrating!!!

Omg, this is fascinating!

“Narrator Davey dragged me across the line with him, and I had no real choice in the matter.”

“I highly recommend that you play it first and then come back.”

Because we’re largely dealing with creations here (both the narrator form of Davey and Coda) there is no actual breach of consent. However, it is that experience of being dragged along that is really important. The feeling of “What have I got myself into? What have I done?” That is one of the questions the game poses and forces you to answer, making this all the more fascinating.

I recently played through TBG and enjoyed it very much. I think that the arguments presented here are weak, however. The identity of Coda is uncertain, and our lens is distorted by Davey, so there’s a whole lot of room for interpretation – but if we’re determined to say that Coda is female and that it’s being deliberately (if subtly) suggested by the author, we have to throw out a huge amount of the narrative that we’re given. That’s the downside. If Davey isn’t just embellishing the truth a little here and dropping a convenient bridge & lamp there, and instead he’s fabricating large amounts of the story from whole cloth, where does that really leave us? At that point, we’re dangerously close to saying that Coda doesn’t exist and was just created by Davey to tell a story. Which is true if we’re talking about Davey the author rather than Davey the character! But it kind of misses the point of the story.

The upside of a new interpretation is when it gives us a new foundation for observation, new insights into the work. To be blunt, I do not think you’ve presented sufficient new insights to be gained in your article. Males as well as females can be pushy, or can be repulsed by creepers. People have boundaries, regardless of their gender. You could make a strong case that women have their boundaries ignored more often than men, but that’s a commentary on society rather than an observation about this work.

The only part that’s grounded in TBG is the presence of a woman in the jail – I’ll give you that one! But I think it’s quite a leap to conclude that Coda is a woman based just on that. She’s a prop that’s been added to a map by Coda; can we really assume that’s the author depicting herself rather than representing himself? She’s immediately sympathetic, and the player should be able to identify with her whether the player is female or not. It’s reasonable to think that Coda would be able to sympathize as well.

Coda is a mostly blank canvas. If TBG is successful as a work, players identify with Coda by the time it ends regardless of their gender. In a very real way, it doesn’t matter to the story what kind of person Coda is. But if an interpretation throws away so much of the narrative we’re given in the story, it needs to provide some equally valuable insight. I’d suggest if we REALLY want to stick with the ‘unwanted romance’ angle, we’d be better off asserting that Coda and Davey are gay, which would allow you to access the same emotional angles for interpretation but wouldn’t require stretching the narrative as far to achieve it.

(P.S. Your comment about “Makes game. Includes door. Cannot open door. Thanks.” seems pretty flawed, unless you’ve looked at the level and determined that there is actually something behind it. Most levels include a pile of unopenable doors, they’re functionally just decorative walls. I just finished TBG myself, so haven’t started pulling apart level geometry (although I did hear there was at least one interesting quirk in there!), so if you HAVE looked and there IS something behind there, I retract my criticism but do think that you probably should include a note about that in your article)

Hey this is late, but if I were you I would examine more deeply why you have such a kneejerk objection to the idea that Coda could be a woman, and why a woman Coda somehow makes Coda not a “blank canvas” anymore. Davey is an incredibly unreliable narrator, we literally can’t trust anything he says or does. He only cops to one case of editing Coda’s games, and otherwise never addresses his own meddling in any way; how can we be sure? Isn’t that kind of the point, that we can’t?

You’re also not addressing the girl’s voice in Whisper. If you want to stick really closely to Davey’s interpretation of things, then Coda is a recluse who makes these games himself and shows them to few people. Why and how would Coda involve another person in his games as a voice actor? If it’s a friend then Coda isn’t a recluse and does share his games with other people to some degree and Davey is a liar. If the voice actor is Coda himself, then there’s a possibility Davey is using the wrong pronouns but it’s also totally possible that he’s using the right ones.

Because this means that Coda could also be a trans man or nonbinary person who prefers “he” pronouns, but who has physical traits such as his voice that people mistake for a woman’s. The fact that Coda chooses a woman as an avatar for his most vulnerable moment is very significant and actually made me wonder if he might be a trans woman before I read this article. Also, there’s more voice acting in this part, specifically of a woman crying. Sure, this could be a sound effect Coda used, but we’ve already heard what sounded like a woman’s voice in Whisper, so that’s two. And this is an extremely personal game on Coda’s part.

The only reason I can think for Davey (character) to use the wrong pronouns on purpose is to legitimize his subject. Maybe Davey came to the conclusion that no one would be interested in these games if they were made by a woman, and it’s definitely more likely that with that context people biased against women as video game designers (of which there are clearly MANY) would criticize her work instead of being interested in the person behind the work, as Davey insists he’s trying to do. But at the risk of imposing my interpretation on the real Davey Wreden, it seems to me like if this were an intended facet then Davey would slip on the pronouns and reveal it.

I think a woman or trans person is a perfectly valid interpretation of Coda based on what we’re given, and given how little regard Davey (character) has for Coda as a person (but plenty as a subject for Davey to be an expert about at other people). It’s really clear that Coda’s relationship with Davey was deeply damaging and while this could easily happen to anyone I know it’s also more likely to happen to someone who was raised as a woman, to defer to men, and to get approval from men (because only men are truly qualified after all). Coda put up with Davey’s crap for a very, very long time, and kept sending him these deeply emotional expressions on Coda’s part in spite of Davey’s pushiness. That’s emotional labor, and you don’t do a whole lot of that if you aren’t oppressed on some basis.

Although I guess if he were a creeper maybe he’d specifically lie about just that one part, and we wouldn’t have to throw out the part about them meeting. So, I got too far ahead of myself. I think I’m coming around to this point of view, although I still tend to think that it could be viewed from either side.

P.S. how can do i delete personally embarassing post lolol

…If only I had read just one comment further down, wow. If you see that then I hope you see this: sorry for coming down on you so hard up there! I had the impression you’d made up your mind and got a little heated. These issues hit close to home for me. I don’t know what conclusions you came to as a result, but I’m glad you thought it through some more!

You asked at the top of your comment before this one, “Why did you have a knee jerk reaction that Coda couldn’t ve a woman?”

I’d ask why you had the immediate reaction that this was the interpretation? Much respect for the apology though.

I suddenly found myself smiling when Davey was talking about trying to help out his friend. The things he was saying all resonated with me – those turns towards holding onto ones drive, validation, and connecting with others. And then I suddenly found myself feeling very sad, and very alone, when I saw those words on the screen: “When I am around you I feel physically ill”.

I didn’t see Coda as being a female, but I think its a cool idea to consider. And while (in the real world) our consent should never be violated, I was glad it happened in the game.

I had this face-turn-heel moment where I realized I was just like Davey. I connected on some base level to the things he was saying. On the outside, entitlement and validation (as themes) were just one layer of the onion to see. Why does Davey need to feel so entitled and validated? I think the answer is because without those things, Davey (or anyone struggling with anxiety and depression) will literally crumble beneath the weight of their feelings. That’s not a reason to validate what Davey did to Coda. But the game puts its player in the exact same position as Davey: you feel like the developer owes you something, and they shouldn’t “violate” your trust in what they should deliver. I didn’t really view that violation as a breach of consent, though, on the player.

I think the *player* is the one who is actually breaching the consent – the consent between a player and creator. It’s what Davey did to Coda (the code dev. for the game). It’s what I did to the game as well.

So, you make a game. And then someone plays that game. And suddenly they have all these expectations. That you’re gonna make it nice for them, show them a good time, make it interesting and above all never disappoint. But when you make something, do you really owe anyone anything? When someone writes a blog post, are they obligated to make it something I like? Is that a breach of consent?

It applies in life as well. People are always expecting things from other people, and assuming to know them. In reality, we never know people. Like Davey said at one point, people always miss the little nuances that make a person unique. But the person you’ll have the hardest time reading is yourself.

I see Coda as being a part of Davey – as being the voice of sadness and fear that whispers to him, “When I am around you, I feel physically ill”. What if that voice was a part of you? What if you couldn’t live to enjoy life because of that?

Do realize that not only did Davey throughout utilize the pronoun of “He” for the questionable character of “Coda”, but in theory, Coda is Davey himself.

Though It’s debatable; to say that feminism is the soul charter behind said game – is completely out of question.

To the average viewer, the game derives the path to which coda forged and deviated from whilst creating his own form of therapy – abstract games.

Alas there is no solid or foundational evidence from The Beginners Guide to promote any form of feminist agenda or ideology.

I’d advise playing the game from a perspective to which Davey himself would want you to look at it from – the one to which focuses on the alleged emotional and psychological collapse of Coda, and the relationship between the two. Just as Davey asked in the beginning befor releasing his email.

Searching for specifics pertaining to feminism will only come up with misinterpreted doctrine.

If that were true, I would feel sorry for the “average viewer.” However, I think most people have better reading comprehension than you do. I’d advise reading up on logical fallacies and thinking real hard about the type of energy you’re putting out into the universe. <3

So, as recommended, I bookmarked this and am now revisiting after having found the time to actually play the game… and I’m supremely glad I did, not just to avoid spoilers, but also because I had a very similar reading of the game–in particular, a very strong sense that Coda was in fact female–and I don’t have to wonder if that perception was colored by your (excellent) review.

One thing that is still nagging at me is WHY Davey would lie about Coda’s gender? My first impulse is that it’s to obscure his romantic interest, to make himself look “better.” But I also wonder if it’s another way that Davey is choosing to dehumanize Coda by projecting his own ideas and feelings onto her (if she is indeed female)? He’s so invested in feeling that his own self is reflected in these games that he refuses to grapple with the reality that a female developer is going to have a perspective that is going to differ from his, and in doing so, he renders himself incapable of actually learning anything from Coda’s games. I also think it could be a demonstration of Davey’s wildly inappropriate disrespect for Coda’s boundaries, in that Davey might perceive that by changing Coda’s gender, he’s “protecting” her from being seen as a “lady developer,” something that he assumes will color the way Coda’s games are seen, but there’s no indication of whether that’s something that Coda WANTS to be “protected” from… although given that these games aren’t meant to be seen by anyone, it probably isn’t.

@beynotce I’m so happy you came back to share these thoughts! I really like your theories on why Davey would lie about Coda’s gender. Especially the “protection” idea.

Wow.

My brother is a games designer – I shared this with him and he thought it was a great review, and responded with this:

I cried after playing it, there’s so much to identify with. Sarah finished it and was almost inconsolable. Really powerful stuff. How Davey’s narrative shows you his interpretation as fact until at the very end when Coda gets to tell their side of things and it hits you like a punch in the chest. With games, I guess you become complicit in the act because you’re the one actually carrying it out. You’re the one enjoying things until it’s too late when you hear that you’ve massively overstepped your boundries. The contract going in is all lies and there’s a great deal of shame to be felt for doing so.

I to think it is a bit vague to begin and gender determine Coda – In fact I see little evidence that Coda actually exsist at all.

First off, he is never called anything but Coda, however, Davey states several times what great conversations and what great friends they are, but he never uses his or hers name.

Second, Davey always talks to Coda about games, and have a VERY deep insigt into Codas games, despite he states very cleary and very early on, that Coda actually deletes all the games he/she produces as soon as they are done. Why is this? And why do Davey have full acess to the source code?

In my opinion Coda is Davey, and Davey is Coda. Coda is the subconscious part of Davey with all the creative juice that comes with young age, but as Davey gets older and more educated he struggles with the concept of making meaningless stuff, so he starts to corrupts his own creative ideas.

That is also why Davey knows everything about Codas emotional state at all times, and why Coda at some points seem to be struggling with Daveys ideas.

Also remember that Davey wrote The Stanley Parable, which essentially is about choice, and the battle between the inner levels of your own psyci

…you realize that “he” is a gendered pronoun, right?

Late to the party but I just wanted to say I’m so glad I found this post, because I had the exact same reading of Coda being a woman and it was bugging me that it didn’t seem to be a common reading amongst the other articles I found! So thank you for reassuring me it wasn’t just me. :D

That’s an amazing article. Thanks for all your interpretations on the game.

I think I’m going to play it again (just finished it).

I too got the feeling that Coda was being misrepresented even before I got to the point where I realized just how wrong it all was. I had to ask for a refund of the game because it hit too close and made me feel suicidal and ill, as if I had personally done something horrible (in playing the games) and had hurt Coda, contributed to their pain and I needed to make amends for it in my own blood. (Not to worry, I didn’t actually follow through on the urges to self harm, but the fact that the game provoked those urges told me it was very unhealthy for me and I had to return it so as to alleviate my guilt in the only way I could)

My interpretation of Coda themselves was possibly that the narrator had indeed met Coda and Coda appeared to be male, but was not. They were trans, a woman trapped in a man’s body. That only added to my feeling of wrongness. That Coda had been twice violated, not only in having their games be shown and altered without their consent, but that even the gender they wished to be represented by was being denied them.

Hahahahaha, you completely missed the whole point of the game in your desire to make it “feminist”. See what you want, it doesn’t make it real; the true hallmark of a feminist.

You wanna elaborate there bud? Or are you just gonna vaguely claim that without actually making a point?

Like your take on it. Such a great work that breeds such different interpretations. Supporting yours there’s the fact that Davey tells he met Coda at a Jam but there aren’t any game jam games in the Beginner’s Guide. I mean, sure, some of them could be from game jams, but it seems unlikely, in my experience. Also, Coda clearly is reclusive and I don’t really see hir going to game jams. Your review got me thinking maybe Davey hacked or even physically stole Coda’s computer, which would explain why he knows of the renaming of Coda’s Recycle Bin folder.

The idea also pops in my head maybe SHe did go to game jams and stopped because of Davey’s stalking, at least partly.

Either way, it really hurts.

Thank you for receiving this communication.

Interesting comment, but I think you are falling in the same trap that the game is warning about: over-projecting themes in an attempt to fit something to your own narrative. Of course, we can say every interpretation is equally valid, but the greater point of the game is about twisting and turning to create your own pet interpretation sometimes is not valid.

In my opinion, your comment about “being dragged by the narrator”, is absurd. Every narration, by itself, entangles a particular vision and story. Sometimes a narrative drags you to a place you don’t want to go, but that’s the point of a narrative, to lead you some mental experience, otherwise, we would need “spoiler warnings” for every book. “Warning: at the end, Don Quixote recovers his sanity and dies somewhat disappointed. If you don’t want to be dragged in this kind of satiric narrative, I recommend you to stop reading now”. It’s absurd, if you ask me.

In my opinion, the game is about projection, and the difficulty of demanding creative processes and how it affects personal relationships. It’s a reflection of thematic narrative and how projection can twist ideas, and in the end, creating something that the author never wanted to be there. But, perhaps it is there, after all, because someone saw it. Who knows. It’s an invitation to reflect, not to interpret metaphorically, I think.

. . . she specifically bases her argument on the basis that Davey never met coda and eventually quotes Davey saying he met Coda at a convention.