June was LGBT Pride Month, so we decided to extend our pride all summer long by feeding babies to lions! Just kidding, we’re talking about lesbian history, loosely defined as anything that happened in the 20th century or earlier, ’cause shit changes fast in these parts. We’re calling it The Way We Were, and we think you’re gonna like it. For a full index of all “The Way We Were” posts, click that graphic to the right there.

+

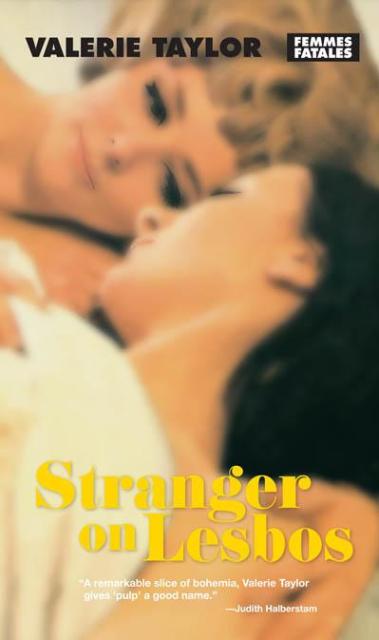

I was excited to review Stranger On Lesbos, a re-released pulp fiction novel by Valeria Taylor coming to the entire world in 2012 via the Feminist Press. The Femmes Fatales effort they conduct brings generous amounts of retro women’s writing back into our hands, thus allowing us to fondly and not-so-fondly remember the days of yore.

Strangers is the first of a small and short series of books by Taylor focusing around the same central crew of characters.

In Stranger, we become well-acquainted with Francis, a woman suffering from Betty Friedan’s “problem with no name.” Her husband, Bob, has finally hit great success in his sales career, which has resulted in presumed affairs and a new sense of isolation for her in the wake of his heavy workload and recent relocation to Chicago. Her only son, Bill, is reaching adulthood and has a sense of independence making her feel purposeless, uneeded, and worse — bored and unhappy. She is completely unsatisfied; as a temporary solution she seeks out collegiate courses nearby to stimulate her mind and give her something to busy herself with.

What she finds is a new friend — Bake, a butch woman who wears lipstick and sits near her in an english class. They spark up a friendship over drinks, which is a typical recipe for lesbian disaster, and mere chapters later confess their love for one another in front of Bake’s fireplace.

Even as her romance with a woman unfolds, Francis (now called Frankie, of course) struggles with what that means in a culture where people of her variety seemingly do not exist. What you notice off the bat are the familiar faces in her new second life: the emotionally unstable lesbian and her endlessly loving caretaker, the subtle and sexy ex-girlfriend, the formerly-married lesbian head-over-heels with a hot mess, and Bake — the heavy drinking, intensely passionate, emotionally insulated, and tenderly manipulative love of her life.

Throughout a good portion of the book, Francis finds herself completely willing to sacrifice the past in an effort to seek out a new future. That is to say, one of picnics and long afternoons, a job and a new sense of independence and a stream of gay bars that she doesn’t care for but trudges along to in order to get Bake home safely. What she lacks, however, is the ability to formulate “the right time.” When, for example, does one announce to her husband and adult child, who by this point is at the brink of engagement, that she is surrendering her former title as Trophy Wife for the new title of Femme Trophy Partner? Bake is impatient and insecure about Francis’s inability to come right out and say it, pack up and leave, and move in to her apartment, and Francis finds that Bob makes her queasy and Bill makes her sad. And yet she doesn’t make the move.

The sense of isolation Francis had once felt in her home begins to transfer to her second life as she finds herself outside of normalcy and outside of the realm of understanding of most people. Her husband is inquisitive about her behavior; she has taken up drinking for the first time in her adulthood and often sleeps away. She is in one way protected by the ignorance of the times: unless she is in a gay bar or at some sort of lesbian party, she appears to be with “girlfriends” in the grandmother sense and not in the gay marriage sense — nobody assumes she is sexually or romantically interested in women when they see her on the street because it simply isn’t a possibility in the full expansions of their minds and the minds of an entire culture. But it is also the widespread lack of community, and lack of awareness and affirmation available to her that ultimately challenges her to hesitate, to pause, to ponder endlessly her ability to even embark on such a life full-time. Being queer is Francis’s second life, but her first life is one in which she has a rule book, role models and options. Throwing that away is hard and has tangible consequences for her family and herself.

Throughout Stranger, I found myself in-between the present and the past. There were times where I took big breaths and stared out the bus window and thought, “thank fucking god it is now and not then.” Times when Francis was told bluntly that her lifestyle was a freak choice, an alcohol-induced mistake, an embarrassment to her family. Times when she lacked the ability to seek refuge in any way, or had no one — absolutely no one — to talk to about what was happening in her heart and in her ever-more-lonely life. There were no allies and there was no community. There was simply Francis and her lush lesbian friends who were dating and fucking one another without regard for each other because there was nobody else to love.

In many ways, my revisit to fiction of the 1950’s made me realize even moreso why the movement is important, why our voices are important, why our existence is important. How far we have come.

But in many ways, people haven’t changed. The sun is still rising on hungover butches and their lipstick-stained cigarettes, and on unhappy closeted wives spending their time fidgeting their hands and pondering their next steps. There are too many of us worried still about how our families will feel, how our neighborhoods will react, how our leaders will proceed. As if any of that matters, as if how we feel and how easy it is to somehow disregard or fictionalize or mythologize it makes it any different to try to survive in this world as a weirdo queer.

Ultimately what I felt for Francis was a desire and need for a community, for understanding and for love. Francis is unique in that not many women with “the problem that has no name” turned to other women for their ultimate fulfillment from that problem, or at least not many that we heard of. Francis is unique because she exists in a time when she wasn’t supposed to exist, in a time which we commonly paint as being absent of people like us. But in the end she is exactly like us — shaped by circumstance, torn between what is safe and what is honest, melting with one touch and clinging to each meaningful moment to carry her through the imperfect and painful ones.

I am glad to be here with you in 2012. But I am glad someone was there in 1950.

Valerie Taylor’s work was deeply personal and her journey to writing it was her own life. The Feminist Press website states that with “the $500 proceeds of her first novel, Hired Girl (1953), Taylor bought a pair of shoes, two dresses, and hired a divorce lawyer.” That was just the beginning of a life and a legacy, and in many ways Francis embodied in Stranger Taylor’s own experiences as she grappled with her sexuality within her marriage and eventually made the decision Francis cannot make — the decision to fall endlessly, to plunge into something unknown and unstudied, to subscribe to something admonished and seemingly absent. To believe.

But in many ways, people haven’t changed.[…] There are too many of us worried still about how our families will feel, how our neighborhoods will react, how our leaders will proceed. As if any of that matters, as if how we feel and how easy it is to somehow disregard or fictionalize or mythologize it makes it any different to try to survive in this world as a weirdo queer.

so well said.

Great review! I have a copy of Whisper Their Love reissued by Arsenal Pulp Press (a Vancouver publishing house) in their Little Sister’s Classics series–devoted to putting out of print older queer books back into print. It’s exciting to see that others of Valerie Taylor’s work is being republished as well! It’s so important to know where we’ve come from, and, as you wrote, to see our differences and similarities.

Thanks awesome review. So gonna read this :-).

i love lesbian pulp fiction. definitely going to check out this book. the pulps from that time definitely remind us of where we’ve been as a community and how far we’ve come.