To be completely honest with you, I was supposed to write this review last week. I had it planned for nearly a month, since I first saw a press screening of Netflix’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom right before Thanksgiving. Then an unexpected promotion came with new stressors, and my second and third family members came down with Covid (no one reading this needs a reminder of the astronomical racial and economic chasm of this disease), and like so many of us trying to survive this global pandemic — the depression that’s been prickling behind the corners of my eyes threatens to overtake me every day that I fight to get out of bed. I know you didn’t open this piece about Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom to read a journal entry about my life, but just hang on for one second.

Last Thursday, on the eve of Ma Rainey’s Netflix premiere, I collapsed into a pool of panic and exhaustion — scrapping by to make deadline. At my very wits end, I was reminded by someone I love very much, trying to knock some sense into me: “Ma Rainey didn’t spend herself and her career to carve out authentic creative space for Black queer artists so you’d be out here in 2020 with your own mental and physical health suffering just to write a review of Viola Davis as Ma Rainey to keep pace with Twitter!”

Or to put it in the words of Ma Rainey from the film herself, “We’ll be ready to go when madam says we ready to go. And that’s the way it go around here.”

Viola Davis as Ma Rainey, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (Netflix, 2020)

August Wilson’s 1982 Tony-nominated play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom happens to be one of my favorite pieces of Black theatre. I’ve worshipped August Wilson’s words for about as long as I’ve loved theatre, which is to say my entire life. Across his ten plays, “The Century Series,” one for each decade of the 1900s, August Wilson traces the majesty and impact of the Black communities in the United States. He dedicated his life to a singular project, creating, in his words, “the world of Black America… so that you [Black people] are fully clothed in the manners and a way of life that is uniquely and particularly and peculiarly yours.” I say dedicated his life in a very literal sense, August Wilson’s last play of the series, Radio Golf, was first performed in 2005 at the Yale Repertory Theory, the same year that Wilson died.

With numerous Drama Critics Circle Awards, a Drama Desk Award, a Tony, and two Pulitzer Prizes — Wilson is easily one of America’s most distinguished playwrights. More than that, the feeling watching or reading August Wilson as someone who’s Black — it’s indescribable. It’s as if he’s reflecting back a story that’s long been bubbling within you, just waiting for someone, anyone to excavate it and set it free.

Wilson had very little use for writing about celebrity, the majority of his protagonists are working class or poor Black people — that neighborhood Uncle who talks Real Big at the corner store, your mother sitting over bills at the kitchen table, your brother whose eyes used to shine so bright when y’all were kids but became muted as a teenager, the ghosts of your great-Auntie who haunts the walls. They’re all accounted for.

That Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom focuses in part on one of the most successful Black women of the 1920s (who recorded over 100 songs between 1923 and 1928 alone, and famously performed in a tiara and $20 gold coins as her necklace) is a bit of an anomaly, but its central themes — the white theft of Black talent, PTSD stemming from white violence in Black communities, the specific entanglement of anti-Black racism and sexism faced by Black women — certainly are not. In fact, they’re the entire point.

Viola Davis as Ma Rainey, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (Netflix, 2020)

As this Ma Rainey (in Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s exquisite adaptation of Wilson’s work), Viola Davis’ performance stuns in its magnitude. She’s towering. A woman whose stubborn assurance, wisdom, and refusal to shortchange her own self-worth is larger than life. On stage, she captures the imagination — smiling and writhing, dipping her hips low with emphasis like she’s a Grammy-winning pop star and not the two-time Tony Award wining, Academy Award winning GOAT of her moment. With her close confidants, Davis taps into Rainey’s quiet beats. She’s fiercely protective, harsh and difficult, but not without tenderness or vulnerability. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom has never been a work — in play or in film — solely about its namesake; it could most readily be described as a case study of her band. But in Davis’ hands, it also becomes a complex portrait of a queer Black woman hurricane whose footprints loom over the last 100 years.

There’s Ma Rainey the woman, and increasingly there’s become Ma Rainey the interpretation, the character. The legend exists somewhere between the two.

Gertrude “Ma Rainey” Pridgett was born on April 27, 1886 in Columbus, Georgia. By 14 she was already a traveling performer, singing in cabarets and tent shows around the South, her tours dotting across the region as sharecroppers worked harvest. At 18, she married William “Pa” Rainey in 1904. They traveled together performing as “Ma and Pa Rainey” (after their divorce Ma Rainey kept the moniker, but told people that Ma was now short for appropriately diva-esque “Madam”).

As an adult, she spent decades touring the country, becoming a stunning showstopper. In addition to her famed tiara, feathered headdress, and $20 gold piece necklaces, she often performed in full length gowns, rings on every finger, and carrying an ostrich feather in one hand or a shotgun in the other — all topped off with her gold-capped smile. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom opens with Davis catapulted into one of Ma’s famous numbers for good reason, it’s impossible to capture the full breadth of the Mother of the Blues’ talent via her recordings alone. She was the archetype of the modern Black Diva — just barely squint your eyes, and it’s not hard to see Patti LaBelle or Lizzo or Rihanna walk in her wake.

Ma Rainey threw at least one illegal queer sexy party broken up by the cops (that we know about). In Chris Alberston’s academic biography of bisexual blues icon — and Ma Rainey mentee — Bessie Smith, Alberston writes that Rainey “and a group of young ladies had been drinking and were making so much noise that that neighbor summoned the police.” Of course the cops showed up, ahem, “just as the impromptu party got intimate.” Rainey was arrested with the charges of “running an indecent party” (emphasis my own) and Bessie bailed her out the next morning.

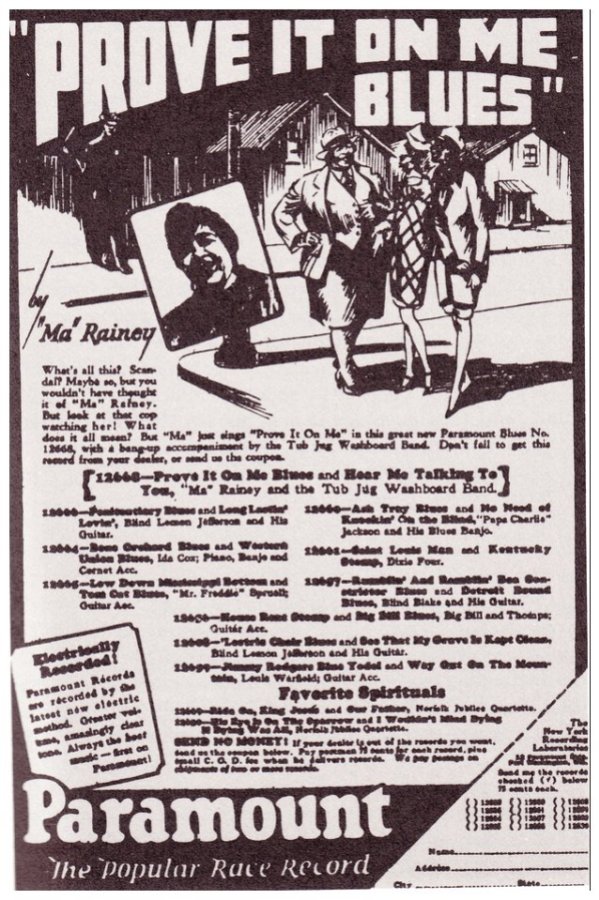

Paramount Ad for “Prove It On Me Blues” (1928)

Quite a few historians agree that Paramount appears to be referencing that infamous night in their ad for Ma Rainey’s signature number, “Prove It On Me Blues.” In the ad, Rainey’s wearing a three-piece suit and tipped fedora. She’s hitting on a group of women while the police watch from the shadows. The text of the first sentence reads “What’s all this? Scandal?”

In their article “Mackdaddy, Superfly, Rapper: Gender, Race, and Masculinity in the Drag King Scene” queer studies scholar Jack Halberstam references this same Paramount ad, noting that it “suggests the popularity… of a particular form of lesbian drag.” Ma Rainey was hardly the only Black woman to wear masculine clothing in the era, Harlem cabaret singer and pianist Gladys Bentley often performed in tuxedo (a style that’s referenced by director Dee Rees during her own interpretation of Ma in 2015’s Bessie), as did Moms Mabley. Both Bessie Smith and Rainey were known to play with masc and femme gender performance at different stages of their respective careers.

“Prove It On Me Blues” also became a key feature in Angela Davis’ Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, a preeminent study of the queer legacies of Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. Of course even one glance at the lyrics and it’s hard not to see why:

“They said I do it, ain’t nobody caught me

Sure got to prove it on me

Went out last night with a crowd of my friends

They must’ve been women, ’cause I don’t like no men

It’s true I wear a collar and a tie…

Talk to the gals just like any old man.”

Ma Rainey was many things, but subtle certainly was not one of them.

Mo’Nique as Ma Rainey, Bessie (HBO 2015)

So we can presume why it’s “Prove It On Me Blues” — and not “Black Bottom” — that’s the backdrop of Dee Rees’ depiction of Ma Rainey in Bessie, which Davis’ outstanding performance aside, is easily my favorite interpretation of her to date. There’s still nothing quite like watching a queer Black woman director bear witness to an infamous queer Black legend in her own right. In the film, Ma serves as a gateway for a young Bessie Smith, teaching her the world of underground speakeasies, sex clubs and gambling rings — both women remarkably handsome as Black femmes in lingerie and flapper dresses hang off them. At first Queen Latifah’s Bessie finds herself timid, but Ma Rainey’s (Mo’Nique, in a staggering performance) bravado coaxes her out of her shell — “Who’s goin tell? They’ve got to prove it on ya, babyyyy. They gots to prove it on you.”

Ma Rainey has been translated on screen by two Academy Award winners in the last decade, the first being Mo’Nique, and that now brings us back again to Viola Davis.

Viola Davis as Ma Rainey and Taylour Paige as Dussiemae, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (Netflix, 2020)

The original 1982 August Wilson play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom settles for implying Ma’s sexuality, but in the film there’s one scene that continues to live in my head rent free. After a morning of withstanding scandalized glares from the Black upper middle class at her hotel and outright racism at the hands of white Chicago police and her record producers, Ma finally has time alone with her girlfriend Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige), a dancer in her band.

Dussie, having freshly applied red lipstick, is dancing by herself in the corner while Ma’s nephew plays piano. Davis’ Ma Rainey looks on, arms crossed, her face a mixture of appreciation and lust, her tongue slightly poking out above her gold capped teeth. She purrs a command to Dussie, “come over here and let me see that dress.”

She wraps Dussie in her arms, slightly caressing the underside of her breasts while both women sway to the music. “I want you to look nice for me, hmmmm…” Davis all but whispers into Dussie’s neck, her voice as much a moan as it is any other sound. She keeps going like that for a while, saying words that are technically words but feel like they’re kisses. Each next one more hot than the last.

It’s as commanding, as controlled, and yet also — as tender, sexy — as I have ever seen Viola Davis. A century’s worth of queer legend about one Black woman coming down to bear in a single moment. Even sitting at home I had to look away, embarrassed by my blush.

Ma Rainey died in 1939 of heart failure in Rome, Georgia. Her death certificate labeled the most notorious Black woman of her time as a housekeeper.

All year I have been waiting for two things: This movie and your review of it. And I knew they’d be gifts of soul and gifts of spirit, but they still both blew me away. Everything’s so much every minute but I get to be alive when Viola Davis is playing Ma Rainey and Dr. Carmen Phillips is writing about it.

This is an exquisite piece of writing, Carmen. Just beautiful.

Ma Rainey’s story is so important, but if someone has to wear a fat suit to play a character then they’re the wrong actor for the role. Viola Davis is incredible, but this role should have gone to a fat Black actress. Fat bodies aren’t costumes, and the way that reviews even on normally intersectional feminist sites are still ignoring this appropriation of the fat body is part of how fat voices are constantly left out.

I agree. Viola Davis is otherworldly talented & still this role should not have been hers. And I wish the fat suit had at least been mentioned in this review which was otherwise great.

I believe she gained weight for the role:

https://www.republicworld.com/entertainment-news/hollywood-news/viola-davis-transformation-for-ma-raineys-black-bottom-sparks-sexism-debate-online.html

For Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Viola Davis gained weight to look like the singer.

Wow. Incredible writing about an incredible performance. Thank you, Carmen.

Dr CP, I know I am not the audience this piece is written for, but I am so grateful to have the opportunity to read it. Beautifully written, you encapsulated so much in each line! I love your writing so so much.

Wishing the best for your family members, and for you.

And yes yes yes you are so important, so valued and we can always wait!

Oh, Carmen, I hope your family members are doing all right! I’ve been thinking a lot about stubborn strength and giving ourselves grace and time, as my abuela also has COVID. The Ma Rainey line you shared near the beginning, of this piece—“We’ll be ready to go when madam says we ready to go. And that’s the way it go around here”—made me pause for a deep breath. Fuerza.

Carmen, I hope your family members recover smoothly and fully from COVID and that you are able to get the rest and support you need. <3 Thank you for this piece; I've been looking forward to it and I learned a lot.

Great one thanks for sharing

Carmen, thanks for this piece. And, I hope your family members are doing better.

I was so struck by the intimacy of how this scene between Dussie and Ma was shot. I think the only other scene quite like it was the concert with the dancers surrounding Ma.

Carmen, thank you for a completely enthralling review.

I hope we get a proper Ma Rainey biopic one day. I wanted more of her, more queerness.

I watched this movie because of this review. It did not disappoint. Great.

Carmen, I so relate to you.

I work for a company that develops and produces hospital and medical supplies/equipment which means I’ve hardly had a day off or restful night since the pandemic hit. I live in a progressive state but I’m from an anti-masker one and all of my family resides there. My family death toll due to COVID is now at 9 and I’m just about at my wit’s end. When I saw the trailer back in October, 5 family members had died since March and for about 2min, I felt lighter than I had in months because I actually had something to look forward to.

Before my grandfather became an evangelical Christian, his mother (my great grandmother) who lived with him and his wife, played one of Ma Rainey’s vinyls on an old record player, while my brother and I danced around like loons. Seeing the trailer reminded me of my great grandmother who was the absolute sweetest woman to ever live and it reminded me of how fun and alive (figuratively and literally) my family used to be.

I have yet to see the film and probably won’t have time to for a bit, but based on your review it won’t sully the memory of my great grandmother or Ma Rainey. Thank you for confirming that this seemingly small thing is still something to look forward to.

That is so much for one person to bear. There’s nothing an internet stranger can say to make it any better but I’ll hold you in my heart today and wish you healing and moments of peace.

I am so terribly sorry. This is devastating, and should never have happened to you and your family. My heart goes out to you with deep sorrow for your losses.

Carmen, thank you for a fantastic review, but also for taking the time you needed before publishing. Please keep putting your health first! I hope your family members recover soon.

Great post keep posting thank you