Welcome to Autostraddle’s APIA Heritage Month Series, about carrying our cultures from past to future.

At ten years old, I held a Cheerios cereal box featuring a white Barbie next to my face while I asked my mom, “Can I get this, please?” Without even looking, my mom responded, “Uh huh, học giỏi đi con, as long as you do well in school.” I felt like the happiest little kid on the block. I looked down at Barbie and saw her beautiful, fair skin. Later that year, I wanted to bleach the brown off of me.

As the youngest of seven kids, I felt the pressure to live up to the sacrifices my parents made for me and my siblings. My life was indebted to theirs and felt like it was never mine to own. The sacrifice of leaving their war-torn home. The abuse they endured trying to come here. The endless hours working to feed us and put a roof over our heads. My older siblings seemed to do a great job of proving that my parents’ sacrifices were not a waste; it only made sense for me to continue that.

A photo of Sal’s family. Sal and their twin Nancy stand at the bottom of the photo.

I did whatever it took to live the American Dream: you can be whoever you want to be with the right mix of ingredients. Add one cup of bleach, four ounces of internalized racism, a slab of self-hate, and let it all braise together, you will have cooked up the perfect child to conquer anything in the American concrete jungle.

To prove my dedication to this dream, I had decided not to speak in Vietnamese anymore. With every Vietnamese word that exited my mouth, I felt the weight of shame pull me away from my sprint towards whiteness. I refused to eat my mother’s Vietnamese packed lunches of cá kho, as beautiful as that braised fish over steamed rice was. I needed to play the game: Lunchables, Capri Sun, and English were all I would accept. There was no room for the smell of fish sauce on my skin. I would rather starve with my own ego.

One day, my mom came home from a long day of work as I came home from school. I was holding a stack of books and tried to explain what I learned in school today in English. She couldn’t understand a thing.“Cái gì? Mẹ không hiểu. Con nói lại lần nữa. What? I don’t know what you’re saying. Say that again.” I fished for a response in Vietnamese. My ego held me down like a rock. “No, mom, that’s not what I was trying to say. Seriously, mom, you don’t understand?!” Frustrated, I slammed my books on the floor and looked her in the eye. “MOM, YOU’RE SO FUCKING STUPID.”

Four seconds passed. Out of all the words I said in English, she heard the ones that mattered. She held back tears as her eyes locked with mine. I could see the same shame in her eyes like a mirror to my own. She slowly crumbled. “Con đúng. Mẹ ngu. Mẹ không đi học giống con. You’re right child. I am stupid. I didn’t get the chance to go to school like you did.” As my mom walked out of the room, all I could feel was the heaviness of her absence. Nothing could describe the betrayal I had committed. I never meant to make her feel so small — to have her believe the words coming from a child poisoned by whiteness. Did I poison her too?

![]()

I perfected the art of disconnecting myself from my own body in an attempt to survive. I adopted anger as a mechanism to protect myself. I held these two skills close to me as I entered one of the whitest universities in California. Being a student unearthed what whiteness had buried in me. It brought me back to the place I was avoiding my whole life — my body. I never realized how painful being in my body was until I had the language to describe it during my undergraduate years. I finally had the tools to articulate the hardships I went through growing up: the unresolved trauma that was carried, compounded, and passed down from past generations into my own DNA. The kind of trauma that lives within the body — and when it escapes the boundaries of our bodies, it can transform into violence in the form of abuse, self-hate and mental health challenges.

To be in my body felt like not only reliving the sexual and physical violence I experienced as a kid, but to finally accept that this pain was mine to hold. To hold pain meant to create space for emotions like grief, disappointment, and sadness. I never had the chance to embody these emotions because all I could feel was anger.

But holding onto anger felt like I was holding onto a burning skillet. I failed to realize how the tightness of my grip was causing myself more pain. If I loosen just a tiny ounce of the grip of my anger, all of the violence I experienced would disappear. Or at least that’s what I believed. Anger kept me alive but I failed to realize that it never kept me safe. Safety meant cultivating a space where I could feel the full range of emotions manifested by those past experiences.

I grieved the safety that I lost as a kid. I grieved the sexual and physical violence I endured. I grieved my hatred for my own brown skin. I grieved the time I used the words I inherited from people who hated us to make my mom feel uneducated and worthless. Slowly, I embraced my anger and grief as natural responses in my queer immigrant life. I remembered the kind of knowledge that no university could ever teach me: the wisdom my mother holds through her love, her stories, and her cooking.

My mother became my anchor during one of the most challenging parts of my life, as I learned to name and navigate my trauma. When she had to escape from her home in Vietnam with no belongings, she looked to the moon as her guide in the darkness. Now, I think of the taste of her food when I need to be guided back home. Not knowing how to cook during college, I would call my mother and ask, “How do I cook this?” She replied, “chút xiêu cái nầy, cái kia. A little bit of this, this, this, and this.” Frustrated, I replied, “But like, how much, Mom?” Without pause, she laughs, “Con sẽ biết. You’ll just know.”

Sal Facetimes their mom as they cook together.

As I figured out how much of each spice to add, the only thing I had confidence in was the memory of how the dish tasted and the happiness it brought me. I knew I only needed to add as much as it took to bring me back home to my mom’s Sunday morning meals. That is when her “you’ll just know” wisdom finally made sense. That is when I knew: I’d arrive home not only with myself but with my mother and with my ancestors.

Through my mother’s recipes, I’m reminded of the resilience that flows in our blood. Instead of disconnecting from my body to survive, I nurtured it. Like me, cooking is hella queer and fluid. Every time I reimagine a dish, it can taste different depending on my mood.“How spicy do I want this dish to be today? “How sweet do I want this dessert?” It’s never fixed or prescribed. That’s what makes these evolving recipes — and the queer experience — so delicious.

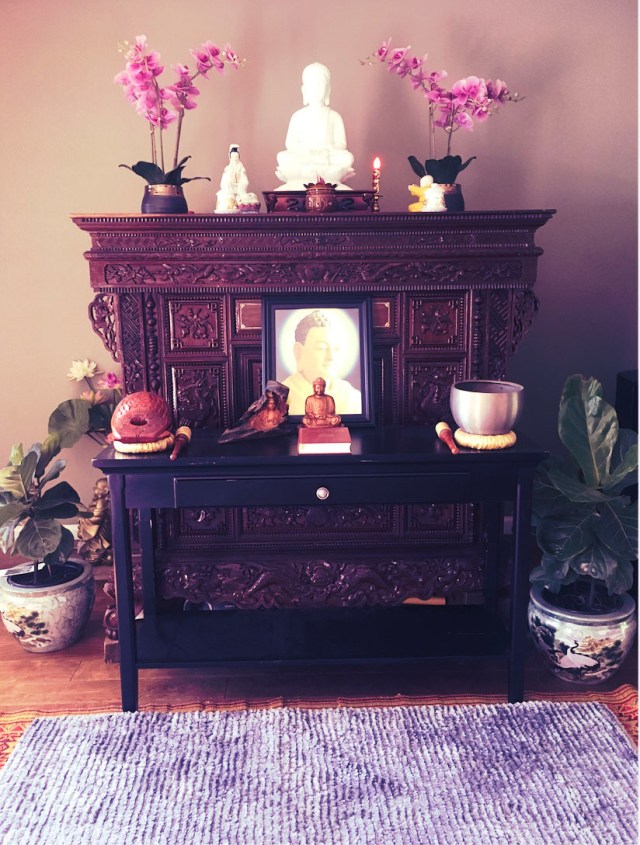

The family shrine, adorned with orchids, incense, and meditation bowls.

We can’t exist if we don’t nurture ourselves. I exist through the recipes passed down by my mom, that have been passed down by her mom, and so on. Our whole lives we’ve been fed things that have disconnected us from our land, our culture, and our bodies. I will never again get lost in the vortex of the American Dream, but I’m always down to get lost in the fish sauce. Because that’s where my mother and ancestors will guide me back.

For more queer stories, food, and tears follow me on my food journey on Instagram Television and YouTube.

i love this essay so much – thank you for sharing it with us. and i LOVE the cooking video, it’s so fun to follow…i can’t wait to try the recipe, and i can’t wait for more of your writing and videos!

Thank you for this, the food looks great!

Love! I just got the cookbook Indian-ish and this reminded me of the way the author of the book connected with her mother and her history through food.

I also really appreciated your description of holding on to the anger until finally facing it and allowing yourself to feel a range of emotions. I’m a foster parent and my kids often have trauma histories, and one took around a year to express sadness instead of just anger.

Thank you for sharing! The recipe looks delicious, I can’t wait to try it out.

Love this! Thanks for sharing!

Thank you so much for writing and sharing! Can’t wait to watch your cooking videos. :)

Thank you for reading. Appreciate you a lot!