Three years ago, we launched this list of queer horror movie moments as both an homage to and queering of the original Bravo docuseries The 100 Scariest Movie Moments, which turns 20 this year. A living list that we add to every year, Autostraddle’s Scariest Queer Horror Movie Moments is one of our favorite annual projects, because we get to engage not only with queer horror history and the early canon, sometimes discovering old works new to us, but also because we get to seek out the best new films adding to that canon.

Below, find our original introduction to this project, followed by a freshly updated list for Horror Is So Gay 3: The Threequel. We’ve added four new films to the list this year and updated some of our blurbs to reflect recent developments, including the fact that 2001’s She Creature is now available to stream, news that should thrill you as much as it did us! See you again next year with more queer frights!

In October 2004, Bravo first aired its iconic five-part docuseries The 100 Scariest Movie Moments. Featuring bloody, haunting, terrifying clips from some of the most revered horror movies of all time along with talking head deep-dives provided by actors, directors, writers, critics, and horror experts, the special was the go-to televised compendium for all things horror.

Last year, Shudder debuted its own take on the cult classic with the eight-part series, The 101 Scariest Horror Movie Moments of All Time. The new list includes plenty of overlap with the original as well as a lot of new entries, especially of films released since 2004.

We’re here to do the queer version.

The horror co-hosts of Autostraddle’s 30 Scariest Queer Movie Moments — Drew Burnett Gregory and Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya — have different relationships with the original Bravo list. Drew watched it obsessively in her youth writing down all the films with a pen and paper and then hunting them down from Blockbuster. Kayla was introduced to it more recently by her girlfriend because for the first twentyish years of her life she avoided scary movies and for the past decade has been voraciously catching up.

As with all lists, no matter how much effort goes into a goal of objectivity, there’s always a lot of subjectivity. “Scariest” especially is a subjective category. And even though between the two of us we watch a wide variety of horror subgenres, there will always be gaps including a few international movies that could have qualified, but proved impossible to find such as 2014 Japanese horror film Gekijōban Zero (also called Fatal Frame) about young lesbians at a Catholic all-girls school and the 2019 Hindi-language film Ghost about a woman murdered by the spirit of her vengeful dead ex-girlfriend. We’re sure there are other movies from around the world that belong on this list that have not been distributed in the U.S.

We decided to open this list up to the entire LGBTQ+ spectrum, but because this is Autostraddle, we are focusing on movies that feature lesbian, bisexual, trans, and queer women and nonbinary people rather than cis queer men. In our minds, this makeup is basically the inverse of a lot of mainstream lists of this nature, which usually tip the scales in favor of works by and about cis queer men and throw just a few slots to the dykes. Why include cis queer men at all? Well, the movies we ended up including that center queer men are groundbreaking, important to the genre, and frequently overlooked.

On a similar note, all of the movies on this list feature explicitly queer content. We only included films with subtext if that subtext is so overt it has been accepted as the text — films made by or with queer creators, films confirmed queer by us and fellow queer horror critics. We’ve also done our best to pick iconic LGBTQ+ horror movie moments in which the horror and violence is not inherently homophobic or transphobic. For example, you won’t find High Tension or any one-note trans killers on this list.

This is the second iteration of this list for Autostraddle, and we’d love to see it grow, expand, and shift. We hope the future of queer horror is less white and less cis. We hope queer horror from around the world is made more widely available. A lot of times, lists like these can have an air of pretension and authority about them — and don’t get us wrong, we do consider ourselves to be an authority on queer and trans horror — but horror, as Drew wrote herself, is a very democratized genre. We encourage you to share the queer and trans movie moments that have scared you the most in the comments! As a general warning, all of the blurbs contain spoilers for their respective movies.

This post was originally written in October 2022 and has been updated in 2023 and 2024.

34. Jennifer’s Body (2009)

dir. Karyn Kusama

Jennifer’s Body is a perfect embodiment of a very specific dilemma: Should I be turned on or scared right now? It’s also one of the most bisexual horror movies ever.

While it belongs pretty squarely in the subgenre of horror-comedy — with a quippy, acidic script from Diablo Cody that also has surprising moments of poetic imagery (“He was skinny and twisted and evil, like this petrified tree I saw when I was a kid” has always stood out to me) — there’s something genuinely frightening about the core of its premise, both in how willing a mediocre indie band is to literally murder a teen girl just so they can get fame and fortune but also, and I think even more relevant to this particular list, the fear of losing a friend to forces beyond your control.

Indeed, Needy and Jennifer’s intense best friendship (layered with erotic undertones, ofc) and its dissolution is the emotional core of the film and also the root of some of its scariest moments. As a horror-comedy, it isn’t full-throttle scary all of the time, but it is brutal and violent throughout, with gore that’s disgusting and enticing all at once. Karyn Kusama is a particular maestro at directing stories about violence and girlhood.

There are specific images that have stuck with me through the years and, among those, Jennifer’s return to Needy after leaving in a van of predatory men stands out. Yes, it’s hard to forget Megan Fox crouched in a corner shoveling rotisserie chicken in her mouth and then vomiting up needly black goo, but even before that, Jennifer’s return as something transformed unsettles. Needy is confused and worried, and Jennifer is covered in blood and dirt. It’s very clear that something very bad has happened. But as Needy waits for an explanation, waits perhaps for Jennifer to break down, Jennifer instead veers in a different direction. Her face stretches into a strange, bloody horror movie smile. It’s a little taste of what will come later on in the movie when her face stretches into something even more sinister.

“Are you scared?” Jennifer asks Needy at the end of the scene. “Yes.”— KKU

33. Knock at the Cabin (2023)

dir. M. Night Shyamalan

At first, Knock at the Cabin just appears like regular home invasion horror. A group of people break into the cabin where gay couple Eric and Andrew are staying with their young daughter. Things get weirder and scarier when those people claim that in order to prevent an apocalypse, Eric and Andrew have to choose someone in their small, innocent gay family to sacrifice.

Things get weirder and scarier tenfold the second you realize these intruders might not just be religious zealots but rather regular people genuinely trying to prevent a horrible thing from happening on a global scale. News reports throughout the film suggest the awful events they warn of are actually happening. Tsunamis, other natural disasters, planes falling out of the sky. It’s all terrifying to watch.

And then during one of those reports, Leonard, the soft-talking member of the group who is introduced as if he might be a villain but ends up much more complicated than that, starts reciting everything the anchor says in unison, suggesting he really did see all this in a prophetic dream. It’s eerie on a lot of levels, but it also just ramps up the fear factor in such a sharp way. What if everything they’re saying really is true? — KKU

32. Midnight Kiss (2019)

dir. Carter Smith

This film does feel like the spiritual successor of Hellbent, the 2004 film that appears next on the list. The murderer even at one point brandishes a weapon that looks like an homage to the scythe wielded by Hellbent‘s masked killer. It similarly features a group of gay men, though Midnight Kiss adds a straight woman to its friend group, too. I could make all sorts of jokes about the “scariest” QUEER moment from this slasher-comedy being something like: having to ride in a car from LA to Palm Springs with your ex and his new fiance, that one friend who won’t shut up about the gay weekend itinerary, having an ominous tarot reading, or toxic tops. The kills are also memorable, including one that features a champagne bottle that’s probably up there with the breadslicer moment from Fear Street as one of the most brutal kills in a slasher from the past few years.

But the scariest moment, if I’m being genuine, is not even one of the main killer’s kills or the tense moments leading up to them. It’s when another character — the resident toxic top, played by Scott Evans — also murders a character in a fit of jealous rage. Killers in slashers are often written intentionally in a way so that we see them less as people, more as superhuman characters, as personas. But here we have an instance of just a regular guy killing someone because he can’t properly deal with his emotions and feels an obsessive need to control those around him, his manipulative nature blooming into outright murder. That’s real scary shit! And I love how Midnight Kiss lets its gay characters be extremely fucked up. I think there are interesting things the film says about how we harm people in our own communities. It’s also just a fun slasher set on New Year’s Eve, and Lukas Gage is fantastic in it. — KKU

31. Hellbent (2004)

dir. Paul Etheredge

In 2004 slasher Hellbent, a killer in a devil mask targets gay men with a very sharp scythe. The central friend group feels very real in all its dynamics, which heightens the horror by providing clear and affecting stakes. It’s a slasher that doesn’t get too bogged down in mythology or motive — while the killer indeed specifically murders queer people, he doesn’t seem driven by any kind of moralizing force. He is more Michael Myers than Ghostface in that his violence doesn’t really have a point at all. Only an unfortunate subplot of its main character desperately wanting to be a cop mars an otherwise satisfying slasher.

Hellbent has creative and memorable kills. (I mean, it’s hard to go wrong with a weapon as showy as a scythe.) Most of the movie is set at the West Hollywood Halloween Carnaval where all sorts of queers are dancing, cruising, and living their best Halloween lives — minus the killer on the loose. While the moment depicted on its movie poster of a scythe against an eyeball is indeed a striking image, the scene that truly stands out is its dance floor kill. I’m a sucker for a dance floor scene in general, and dance floor kill? Well, it’s one of the best scenes Killing Eve ever delivered.

In Hellbent, it’s also a moment to remember. There’s something about a dance floor that really lends itself to a perfect blend of horror and erotics. (The sequence in Jacob’s Ladder is a prime example.) Body parts flung about, a closeness to strangers that implies risk and vulnerability, disorienting lighting casting shadows, and loud sounds that might drown out other loud sounds. Indeed, of all the kills in Hellbent, this dance floor one is the most difficult to discern exactly what’s going on. But that obscured violence is exactly what makes it scary. — KKU

30. Make a Wish (2002)

dir. Sharon Ferranti

Two years before Hellbent, lesbians made our own slasher. Instead of a gay dance party, we got a camping trip. Instead of a mysterious cruiser, we got a bunch of chaotic exes. Sharon Ferranti’s only feature feels like The L Word if it didn’t take six seasons for them to start killing each other. There is more humor and dyke drama than out-and-out scares. One kill is an exception.

Of all Susan’s exes, Monica (Virginia Baeta) is the biggest ladykiller — even if she turns out not to be the lady killer. Not only did she cheat on Susan (Moynan King), but here she is cheating again, this time with the now “straight” Linda (Melenie Freedom Flynn). After a late night romp, Linda goes down to the water. Monica calls out for her, and when the tent starts to cave in, she assumes it’s Linda messing around. Her face goes from flirty to annoyed to terrified in a matter of seconds. It’s not Linda but the killer using the tent and some rope as a cocoon. Monica struggles to no avail, and when she’s good and stuck, the killer stabs the cocoon again and again and again.

For Monica, being a fuckboi was punishable by death. — Drew

29. Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022)

dir. Halina Reijn

To some, Bodies Bodies Bodies will be the least scary film on this list. To me, it’s one of the scariest.

While other films get their terror from ghosts or serial killers or demon babies, this recent slasher gets its terror from fear itself. Or, rather, the damage that can be caused when people feel fear — especially people who are privileged enough to live a life without any real danger.

The final reveal — there was no killer, the first death was an accident, and subsequent deaths were caused by the group’s paranoia — is not just a great twist. It’s also an indictment of a culture where true crime and fear-mongering politicians have created a society of distrust.

The moment that really gets me is when the girls discover Emma’s body and Alice immediately turns on Bee. As the new girlfriend of long-time friend Sophie, Bee is an easy target for suspicion. Her queerness and her accent probably don’t help her chances once Alice (a terrifying and hilarious Rachel Sennott) decides she’s her new suspect. (For someone like Alice, even an Eastern European accent is enough to other someone!) Alice quickly escalates from accusations to shoving to locking Bee outside in the dark, in the rain, vulnerable to a killer — or, far more likely, the elements.

There’s nothing scarier than a rich — excuse me, upper middle class — straight white girl with a victim complex. — Drew

28. Fear Street Part One: 1994 (2021)

dir. Leigh Janiak

Undoubtedly the strongest installment of the Fear Street trilogy, it is my firm belief that Fear Street Part One: 1994 is more successful at being a “new Scream” than Scream (2022) is at being a “new Scream.” It strikes the right balance of doing a ton of homage and self-referential work while still providing elements and sequences that feel exciting and original. And it’s got a young lesbian love story at its core.

I love a good twist of the knife at the very end of a horror movie, and this first chapter of Fear Street does one quite literally. The characters think they’ve saved the day, stopped the killer(s). Deena is reunited with her girlfriend Sam. “Sam,” she whispers in relief, but Sam says nothing, eyes dead. When Deena looks down, a sharp splinter of wood is plunged into her stomach, Sam’s hand on the other end. It’s completely silent until Sam slowly pulls the splinter out, making a horrible squelching sound. Deena collapses.

There are more disturbing scenes in Fear Street Part One: 1994 (the breadslicer kill is one of the most upsetting kills I’ve seen in recent years, and I mean that as a compliment). But as far as queer horror goes, what could be scarier than thinking you’re safe in your own home with your ex-girlfriend who you’ve recently rekindled things only to realize she cannot be trusted for far worse reasons than what led to the breakup? Deena and Sam’s relationship isn’t perfect, but that’s actually what I love about it. It feels like a real teen relationship, like a real First Girlfriend situation. Maybe they shouldn’t even be together, but they’re still going to literally fight for the relationship as if it’s life-or-death because, at this point, they can’t imagine anything else. — KKU

27. She Creature (2001)

dir. Sebastian Gutierrez

Drew and I put a lot of work and parameters into making sure this list would be comprehensive and not merely a reflection of our personal tastes. That said, as we touched on in the intro, true objectivity is an impossible and sometimes stifling goal. The 2001 made-for-television film She Creature deserves a place on this list; I’m also confident that only a list made by me and Drew would feature the 2001 made-for-television film She Creature. For one, it’s hard to find. We stumbled upon it somewhat accidentally in our research. For two, it’s weird as fuck.

(In an exciting 2024 update for this entry, She Creature is now available on Tubi, under its alternate title, Mermaid Chronicles Part 1: She Creature. A part two was never made.)

She Creature is about a carnie couple played by Rufus Sewell and Carla Gugino who are transporting a captive mermaid by ship in order to make riches off of her in America. The mermaid, it turns out, has psychic abilities as well as a tendency to murder men.

It might not sound very obviously scary or very obviously queer, but if there’s one thing that pushes the movie to surprising heights on both fronts is the performances — particularly by Gugino and Rya Kihlstedt as the mermaid. In many ways, this is your typical monster movie. In many ways, this is absolutely not your typical monster movie. The mermaid develops a psychic connection with Gugino’s Lily that is also, undeniably, a sexual connection. There’s never a kiss between the two, but there are multiple almost-kisses, and this psychic-sexual connection makes for an original premise that’s titillating and terrifying — especially since Lily doesn’t really know what’s going on for much of the time.

While there are also some great nightmare sequences leading up to it, we ultimately decided to highlight the mermaid’s transformation, often the best part of a creature feature. She Creature really saves it for the end, up until this point the mermaid only appearing as a cliche beautiful, seductive woman. She takes her true form right before leading the ship full of men to their slaughter, the monster coming out. — KKU

26. Sissy (2022)

dir. Hannah Barlow and Kane Senes

Two of my biggest frustrations with modern horror cinema seem to be in conflict. 1) The historical and immediate trauma of marginalized groups is used for cheap scares rather than meaningful engagement. 2) An attempt at inclusivity is made without acknowledging how race, sexuality, and disability impact a storyline. But, in fact, both of these extremes are making the same error. They are remaining on the surface when the best horror dives deep within reality.

Sissy, unfortunately, falls pretty squarely in the latter category. It wisely casts the wonderful Aisha Dee as its lead and has a diverse cast, but falters when it tries to engage with the specific experiences of those characters — or opts not to engage at all. It’s frustrating, because what the film does well, it does really well. It commits to nastiness and gore in a way similar films do not and Dee is almost good enough to make the whole thing work.

It’s a tribute to Dee’s talent that the scariest moment is not any of the brutal — and, I mean, brutal — kills. It’s when Dee as the titular Sissy — excuse me, Cecilia — is attempting to make herself look like a victim. After coming from her latest kill, Cecelia sits in silence as a creepy work of art seems to speak to her. She smiles. She laughs. And then she brings back her unsettling rapid breath technique from the film’s opening and begins smacking her face with her phone. Suddenly, this horrifying display stops and she unlocks her phone to play the victim on Instagram live.

It’s a frightening tour-de-force and hints at what Dee could achieve in a more thoughtful work of horror cinema. — Drew

25. Tom at the Farm (2013)

dir. Xavier Dolan

Queer horror has always explored the line between fear and desire. That’s why this list has almost as much sex as it does death. The sexiest moment — and one of the most emotionally devastating — comes from Xavier Dolan’s underrated thriller. (His best film IMO.) Dolan plays Tom, a queer from Montreal with dyed blonde hair, who goes to rural Quebec for his boyfriend’s funeral. His boyfriend’s family didn’t know about Tom — supposedly — and Tom begins a complicated psychosexual relationship with his deceased boyfriend’s hypermasculine brother, Francis (Pierre-Yves Cardinal).

There are moments in the film with more obvious horror, but the one that stands out to me is when Francis chokes Tom. The choking is goaded by Tom, and Francis even says: “Tell me when to stop,” and “You’re the boss.” Tom tells him to choke harder. All he can do is note that Francis smells like his brother smelled, sounds like his brother sounds. It’s here that we really feel why Tom is continuing to put himself in danger by staying with this family. It’s self-harm induced by grief. He wants to feel pain. He wants to die. This single moment holds sex and grief, arousal and fear. For queer people, the desire to be fucked has often been paired with the smell of death. — Drew

24. Cuckoo (2024)

dir. Tilman Singer

Is Cuckoo a great movie? It is not. Does it have a great lead performance and some really striking sequences it does?

Before the film gets bogged down in muddled lore and confused character development, it has a killer hook: a trans girl named Gretchen (Hunter Schafer) is working the late shift at a remote hotel owned by a man with unsettling vibes. These late-night sequences are scary and culminate in the film’s best moment.

We’ve already seen that Gretchen can handle herself well on her bicycle. But as she bikes toward the hospital and to safety, a shadow appears behind her. The shadow of… a creature? It looks like a woman, but no person could run at the speed of the bike? That’s when the film utilizes its greatest formal trick. The sound design grows disorienting and time seems to slip. The woman/the creature/whatever she is gets even closer until BAM Gretchen crashes into the hospital door.

The film will explain the circumstances surrounding this moment, but it never reaches its thrilling height. — Drew

23. Knife + Heart (2018)

dir. Yann Gonzalez

In Knife + Heart, the connections between sex and death are explicit. Voyeurism is baked into the premise: Set in 1970s Paris, it’s a slasher in which a killer is offing gay porn actors. It evokes Peeping Tom in its positioning of horror as inherently voyeuristic and hides a blade in an even more memorable prop.

The queer characters of Knife + Heart are wonderfully complex, and the words you’ll soon read from Drew in the top half of this list on Hitchcock characters and dimensionality vs. palatability absolutely apply here. Gonzalez executes a queer slasher with a queer killer so fucking well — especially because its killer is not its true villain. Anne is.

Anne is a lesbian director of gay porn, and when one of the guys she regularly works with is brutally murdered, she pivots to working on a new project that is literally a porn retelling of the murder case unfolding around her. People keep dying, and she keeps going. Anne’s heartless in this way, seeing tragedies as fodder for her films and, in fact, this vampiric quality of her creative practice ends up being the root cause of the violence that unfolds in the movie.

This is a slasher without a final girl, a horror movie with a tremendous amount of empathy for its killer but without downplaying the impact of his violence in the community. Everyone is complicated as hell, and the movie plays with various tropes, casting Anne as the one who’s trying to solve the murders but also as a presence almost more nefarious than the killer himself. She stalks and assaults her ex-girlfriend, the editor of her films. Anne’s twisted obsessions are dangerous to everyone around her, and she is the movie’s monster. Near the end, she sits in a movie theater watching her own films, no doubt delighting in her own genius. In a nightmare sequence — that’s fueled less by guilt IMO and more by her alcoholism and tendency to turn what’s happening around her into spectacle — the bodies of the dead grab her as if to say this is all your fault. It’s haunting and disturbing, and while Anne’s fear is palpable, you don’t exactly root for her to escape this nightmare. Knife + Heart fucks with you in that way. — KKU

22. Nope (2022)

dir. Jordan Peele

No one has had a greater impact on horror cinema the past decade than Jordan Peele. But none of the work he’s produced or inspired has matched the three masterful films he’s written and directed. His latest is about OJ (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald (queer actor Keke Palmer playing queer), siblings whose family have long been Hollywood horse trainers, facing off against a UFO. There’s a lot more going on in the plot and a lot more going on in the film, but I’ll spare you since this movie made over 120 million at the box office and a lot of you have seen it.

The obvious moment for me is after the reveal that the UFO isn’t a ship but the alien itself — a giant monster in the sky we’ve just watched suck up dozens of people. OJ is out in the truck. Emerald is in the house with Angel, their loyal Fry’s employee, and it’s pouring rain. Nope is as much an action movie as a horror movie, and this is an enthralling sequence. But oh God, when the screams of people can be heard from inside the alien! When blood starts raining down! The jumpscare when the alien spits back out any synthetic objects! The sequence ends with OJ locking his car door as if that will do anything. Humor, horror, and action all in one. — Drew

21. Memento Mori (1999)

dir. Kim Tae-yong and Min Kyu-dong

A Nightmare on Elm Street may have the most famous teen girl being haunted by a ghost in class, but the second film in the Whispering Corridors series has one to match. After finding the journal they shared, Min-ah (Kim Gyu-ri) grows obsessed with her classmates Shi-eun (Lee Young-jin) and Hyo-shin (Park Ye-jin) who have, let’s say, a homoerotic friendship. Min-ah wants to be a part of this connection, even as she observes the distance that’s grown between them. Her obsession only increases after Hyo-shin jumps off the roof of the school.

Min-ha is reading the journal in class when she sees the words “memento mori” glued on letter by letter. She removes them revealing a translation: Remember you must die. As Min-ha reads these words, Hyo-shin’s hands begin crawling up her body. They reach under her skirt, and Min-ha makes a sound that’s something between a scream and an orgasm. She has finally achieved Hyo-shin’s attention — unfortunately it arrived only in death. — Drew

20. A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985)

dir. Jack Sholder

Speaking of A Nightmare on Elm Street, the sequel is so gay it got a whole documentary about it. What it lacks in Wes Craven’s unique genius, it makes up for in bigger set pieces, campier kills, and, yes, loads of gay subtext. This time around, Freddy has abandoned his dream killings to take possession of closeted teen Jesse Walsh in real life. Jesse fights his inner Freddy with the same intensity he fights his confusing sexual feelings.

After a failed makeout with Lisa, Jesse runs away to popular bro Grady’s house and begs Grady to watch him while he sleeps. Grady falls asleep too (classic) and, before you know it, Freddy has replaced Jesse and has Grady up against a wall. Grady’s parents shout against the locked door as Freddy slashes his famous claws through Grady and the door. The most horrifying moment is after Jesse changes back and has to witness what he’s done. Mark Patton was cast for his queerness, and it results in a tortured protagonist who sympathetically grapples with emotions he can’t control. While the movie may have set out to make homosexuality the evil within, Patton’s sympathetic performance results in a movie that’s both scary and goofy about a bisexual boy learning to overcome shame. — Drew

19. The Strings (2021)

dir. Ryan Glover

Named the fifth best queer movie of last year by Autostraddle — aka me — and the subject of this recent essay of mine, if you still haven’t watched The Strings, I don’t know why! It’s a beautifully shot slow-burn of a horror movie about Catherine (Teagan Johnston, who also wrote the film’s excellent music), an indie musician going through a band breakup and a breakup breakup. She secludes herself in the icy world of her aunt’s empty house, working on music and flirting with a local photographer.

Most of the movie is spent watching Catherine drive, drink, walk around, and try to make music. But the benefit of this measured pace is, when the scares start, they have the shock of a horror jumpscare and the surprise of Jeanne Dielman’s burst of violence. The first of these moments occurs almost an hour into the film. Catherine is in her makeshift studio working on music. We then cut to a wide shot in the kitchen. A door opens, and we assume it’s Catherine, but no one is there. The camera then tracks over to the other side of the kitchen where Catherine is cooking. The camera tracks back to its initial position and reveals a figure standing in the doorway. Suddenly the door slams! And then reopens, the figure gone. Catherine enters the frame and walks through the door. The soundtrack is completely silent. We wait and wait and wait until finally she reemerges. It’s an expert bit of horror filmmaking. There are no expensive effects — just a good performance and some incredible camerawork. — Drew

18. I Saw the TV Glow (2024)

dir. Jane Schoenbrun

I’m very fortunate to not only be out as queer and trans but to be so immersed in queer community, that I’ve only experienced certain discourse surrounding Jane Schoenbrun’s sophomore feature from a distance.

Based on tweets from other trans people and Emily St. James’ beautiful essay, there is apparently a contingency of cis people who do not think I Saw the TV Glow is about transness. I don’t even know how to respond to that. In fact, the only way I have responded is to scoff and move on with my life.

I really appreciate Emily’s hopeful read of the ending. That doesn’t mean the possibility it suggests isn’t still terrifying. While much of the film mirrors the tone of its Buffy inspiration, the end is when Schoenbrun most returns to the kind of horror embodied by her first film (more on that later) — it’s the kind of horror that sicks in your chest.

Here, it portrays our protagonist trapped in a life unfulfilled. It’s a fun house mirror of mundanity. Normal becomes the most abnormal thing possible. There is still time, but the possibility of time lost can still be frightening. — Drew

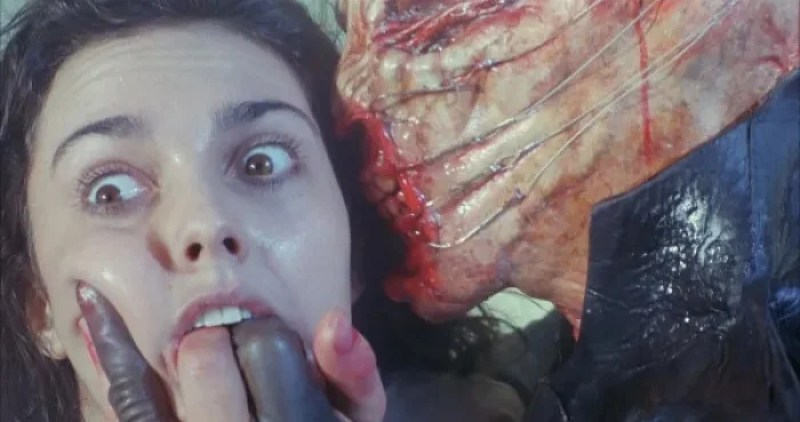

17. Hellraiser (1987)

dir. Clive Barker

Clive Barker invented his own visual language with the original Hellraiser. The film calls to mind words like fleshy, squirty, spitty, bloody, meaty, sticky, grimy. It’s gorgeous in its grossness — not in the typical way of hyper-stylization or artfully turning body horror into something lovely but in just how truly, baldly gross it is. That is not only the point but something to be desired. Pain and pleasure are indistinguishable here. It’s a kink classic, one that Barker makes with no capitulation to straight-laced viewers. With Hellraiser, Barker holds up a mirror to the stigmas toward BDSM and forces people to look right in the face of what makes them uncomfortable.

It was difficult for us to choose a particular moment from this classic — not because it isn’t scary enough or queer enough but rather that it feels so very scary and very queer all the way down to its bone marrow, making it difficult to rip its limbs apart to isolate just one thing. As Drew wrote in her review of the new Hellraiser, sometimes subtext is more evocative than text. Hellraiser (1987) oozes queerness from every oriface, and Pinhead and the pain-loving Cenobites exist beyond gender binaries and also rigid definitions of sexuality.

For me, the moment forever burned in my brain is when the Chatterer’s fingers enter Kirsty’s mouth. It is, to say the least, not a common way for a monster to restrain someone. The Cenobites sure are inventive in their displays of pain and torture. And while fingers down a throat aren’t even close to the most graphic part of this gay gore fest, the shot epitomizes so much of what the original film does well, not just blurring lines between sexual and brutal physicality but erasing them altogether. — KKU

16. The Haunting (1963)

dir. Robert Wise

This 1963 adaptation of the iconic Shirley Jackson gothic novel The Haunting of Hill House is much different than the later Netflix miniseries adaptation, but I’m drawn to both for a lot of the same reasons. In both, Hill House itself feels like a living, breathing thing. A cursed thing. A haunted house whose hauntings are conveyed not always by what can actually be seen but by what is not seen and by what is heard. Strange sounds in the night, a floor plan that doesn’t really make sense, a phantom squeeze of a hand. The two adaptations touch in little ways, especially in some of the imagery in both and in the tracking shots used in the titular haunted halls.

Also, even though it was made over half a century before the world met Kate Siegel’s very gay Theodora Crain, The Haunting manages to preserve the implicit queerness of the novel, delivering a fraught queer storyline between its Eleanor and Theo that is, for the time, barely even concealed. I wouldn’t even call it subtext, really. Like much of what unnerves in The Haunting, it’s right there in front of you if you really look.

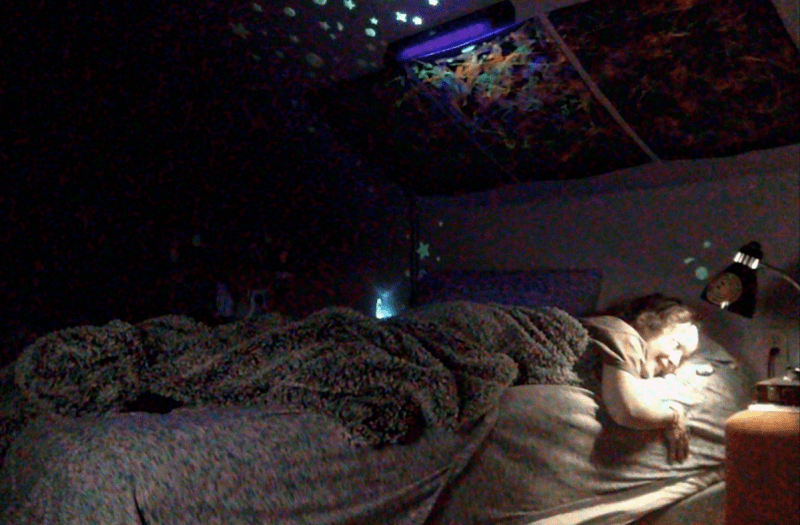

The scariest queer horror moment for this film is quite easy to pick. On their second night in Hill House, Eleanor and Theo end up falling asleep in the same bed. Eleanor awakens in the night to banging sounds and phantom laughs, the same creepy audioscape that frightened her and Theo the night before. She asks Theo to hold her hand. As the sounds escalate, Eleanor says Theo’s crushing her hand. But when the lights suddenly come up, Eleanor isn’t in bed with Theo anymore. She’s on a fainting couch by herself, Theo nowhere near. If it wasn’t Theo…what…the fuck…was holding her hand?????

There’s always something especially scary about moments of horror that occur in bed, in the middle of the night. In fact, one of The Haunting of Hill House (2018)’s scariest moments — while significantly different in that Eleanor/Nell is a child — also occurs in the middle of the night on a fainting couch in Hill House. The Haunting has way fewer jumpscares and ghosts that are seen, but it’s an impressive feat of horror in just how little it needs to do to evoke general unease and disturbance. Its version of Hill House haunts in subtle strokes. — KKU

15. The Perfection (2018)

dir. Richard Shepard

The fun part about ranking moments is we can include movies that may not be entirely great. I’m not a big fan of Richard Shepard’s classical music shocker, but there’s no denying the effectiveness of its second section. Charlotte (Allison Williams) is a former cello prodigy who has fallen out of the spotlight. She meets Lizzie (Logan Browning), the new star, and jealousy soon gives way to lesbian romance.

After a night of fucking, the two women go full lesbian lets-go-on-a-trip-together-after-one-night cliche. Lizzie wants to go off the grid, and Charlotte offers her ibuprofen for her hangover. This doesn’t seem to help and Lizzie is not doing well as they board a bus around rural Shanghai. Charlotte suggests they not go, but Lizzie insists and takes more ibuprofen. Once they’re in the middle of nowhere, Lizzie really starts to struggle. The sequence goes from a real-life nightmare to a heightened nightmare when Lizzie throws up and Charlotte sees the vomit is full of bugs. Lizzie starts freaking out — fair! — and is convinced she has bugs in her skin. They’re kicked off the bus and, once alone, things escalate again. Bugs are bursting out of Lizzie’s arm and, for the first time, Charlotte drops the supportive act. “You know what you have to do,” says as she holds up a meat cleaver. Lizzie chops, and we rewind to reveal, there were no bugs. It was a hallucination. Charlotte drugged her.

It’s a horrifying sequence and a fantastic twist — if only the rest of the movie lived up to its beginning. — Drew

14. Titane (2021)

dir. Julia Ducournau

I wonder if I’d be as enthusiastic about Julia Ducournau’s sophomore feature if it trafficked in transfeminine imagery rather than transmasculine imagery. I understand why some people have reacted negatively to a film made by a cis woman that shows binding and pregnancy and masculinity to be the stuff of nightmares. And yet, I just can’t dismiss this singular work of art so easily. It’s brutal, but it’s also very funny and very tender. Nothing is simple in this film, and that’s one of the reasons I love it, one of the reasons I respond so viscerally to it.

Many of the film’s scenes of violence are also its funniest or its most oddly beautiful. A few moments stand out as purely horrifying. The first is when Alexia makes her transformation into Adrien, binding her breasts and pregnant belly, smashing her face on a public bathroom sink. But the moment that really gets me is later when Alexia has unbound and is itching furiously at her now very pregnant belly. She breaks a hole in her flesh and is met with the residue of metal. She starts punching at her belly and hitting her head against the floor. She tries to bind again and fails. Her nipples start leaking oil.

The car baby inside her will ultimately be something rather beautiful, but this moment is devoid of that later acceptance. There’s just a person fighting with a body of betrayal. — Drew

13. Lyle (2014)

dir. Stewart Thorndike

While “Rosemary’s Baby but lesbian” is already a compelling premise to me personally, Stewart Thorndike’s hour-long work of trauma horror adds grief to the former’s tale of mistrust. The film begins similarly to the Satanic classic. Leah (Gaby Hoffmann) and June (Thorndike’s real life ex-girlfriend Ingrind Jungermann) move into a new apartment in New York — just swap Manhattan for Park Slope — and pregnant June starts to grow suspicious of the new place, the neighbors, her partner. One important difference is Leah and June already have another child, the titular Lyle.

The tension seems to be ratcheting up slowly until about ten minutes into the film when Leah is on Skype with her friend. She’s talking about how June has been distant and how this house is creepy. She is standing in front of one side of a dividing wall. Lyle is waddling around making toddler noises on the other side. The entire scene plays out in the frames of the Skype call. As this casual conversation takes place, the video glitches, the sound lags. Then Lyle’s noises stop. And Leah hears something else.

“Lyle? Lyle? Honey?”

Leah walks around the dividing wall until she comes out the other end and stops. She starts to run forward but the image freezes. Her friend starts to look concerned. When the image unfreezes, Leah is gone. She’s screaming. Her friend’s screen shuts off, and we just hear garbled wails as we look at her empty apartment.

Thorndike takes the daily annoyance of video calls and combines it with horrifying tragedy. It’s so simple, so expertly done. It creates a real life pain that elevates the rest of the film’s genre paranoia. — Drew

12. Prey (1977)

dir. Norman J. Warren

The predatory lesbian trope in horror often finds innocent bicurious girls returning to heterosexual safety after a brief dalliance with sin. Norman J. Warren’s alien intruder movie Prey stands out in several ways and ends with a far more interesting — and more frightening — twist.

First of all, Josephine and Jessica-Anne are a couple. Jo is not controlling like a sinister vampire, but like a true-to-life toxic, biphobic girlfriend. Their dynamic is honest and the romance of their relationship is confirmed in a lengthy sex scene.

The other major difference between this movie and similar work is the “man” — Kator is actually an alien who has taken the body of a man — does not present an escape from lesbianism but rather a metaphor for abuse. After many hijinks — including Jo force-femming Kator — Jessica-Anne finally breaks up with Jo and falls into Kator’s arms. What begins as a sex scene shifts to a rape scene as Kator’s aggression increases and Jessica-Anne tries to escape. Suddenly, Kator takes his true animal-like form and begins eating Jessica-Anne. It’s graphic and horrifying and made more horrifying when Jo enters the room and sees the tragedy that has just occurred.

For Jo, it’s like looking in a twisted mirror. Kator may be literally consuming Jessica-Anne, but Jo has been trying to consume her too. It lends the film a unique perspective compared to similar, more homophobic tales. The villain here is not lesbianism. The villain is any creature — human or otherwise — who feeds on a person as prey. — Drew

11. Rebecca (1940)

dir. Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock can be blamed for some of our most harmful on-screen horror tropes. His 1930 film Murder! is the earliest example I know of a “cross-dressing killer,” something he popularized three decades later in Psycho. His villains were often queer-coded or flat-out queer. But unlike his imitators, his work stands out in how much affection and humanity he granted these sinister queers. While his influence might have been harmful — not to mention his on-set abuse — the films themselves remain some of our earliest and best portrayals of queerness. The goal cannot be palatability. It should always be dimensionality. This is true if a character is the hero or the villain.

If you watch Hitchcock’s adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca as a love story between the mousy second Mrs. DeWinter (Joan Fontaine) and the older millionaire Maxime (Laurence Olivier), then Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson) is undoubtedly the villain. But if you watch the film as a love story between Mrs. Danvers and the late Rebecca, the villain becomes the murderous Maxime. No matter your interpretation, the best scene, the scariest scene, the gayest scene, is when Danvers confronts Second in Rebecca’s old room, the east wing by the sea. Second has gone in snooping, and Danvers is quick to point out that she’s wanted to show her the room anyway every day since Second arrived. As Danvers fondles Rebecca’s furs and her underwear made by nuns, the ghost of her former mistress, her former lover, haunts both women. Danvers asks, “Do you think the dead come back and watch the living?” For Second, this is a moment of frightening confrontation. But for Danvers, the fear is born from the possible answer, no.

Even if Hitchcock was viewing queerness as a fascinated outsider, du Maurier was writing from experience. Her many relationships with women were widely known, and she wrote about having a secret “male energy.” With this in mind, it’s easy to reevaluate this classic moment. The greatest fear is losing your love. The greatest fear is not being able to express it. The greatest fear is that ghosts do not exist. — Drew

10. Annihilation (2018)

dir. Alex Garland

Much of the horror in Annihilation — the 2018 movie based on the Jeff VanderMeer novel of the same name — is atmospheric. Until it’s suddenly very, very bodied.

It starts with a classic Came Back Wrong setup, Natalie Portman’s Lena reunited with her believed-to-be-dead husband Kane, played by Oscar Isaac. But something’s off about Kane, and it leads Lena to go on the same mysterious mission as him into a zone called The Shimmer.

In The Shimmer, things get increasingly weird and disturbing. Wildlife has mutated, creating new beauty and new monsters, like a gator with shark teeth. These monster mutations get worse as the characters go deeper into the Shimmer, culminating with the movie’s most vicious beast, a bear-like creature far more fucked-up than the words “mutant bear” really encapsulate. It’s a stunningly original film monster — visually and in some of its other details, like the fact that it echoes and amplifies the sounds of its victims in place of a standard growl or roar. The bear shows up right at the same moment as Anya, the lesbian member of Lena’s mission team played by Gina Rodriguez, reaches the peak of her paranoia. Suddenly, there are multiple threats at once, Anya turning her gun on her colleagues and the skeletal, beastly bear threatening to rip them all apart.

The sound alone is enough to make you want to look — or run — away from the scene. And then we never pull away from the horror. The monster kills Anya and rips her jaw off. In addition to being visually gruesome, there’s also the bleakness of the fact that her paranoia and delusions — while technically well founded in the sense that they are indeed being lied to about their mission — put everyone at risk. She contributed to her own death by aiming her defenses in the wrong direction. A lot of times in horror, people might have lived if they’d just worked together and trusted one another. It’s a real-life horror of humanity that people often don’t. — KKU

9. Jagged Mind (2023)

dir. Kelley Kali

It was difficult to select one moment from this film, which is suffused in every frame by its genuinely terrifying premise. Billie (Maisie Richardson-Sellers) begins dating Alex (Shannon Woodward, in a wonderfully villainous performance that carries much of the film) and also begins experiencing blackouts and disorienting visions. Are they premonitions? Memories? Something else?

They are indeed something else — something like a memory but also not. Alex has been trapping Billie in time loops, erasing moments after they happen and rewriting them anew. She does so to cover up her controlling, angry, and abusive tendencies, Jagged Mind‘s sci-fi/horror take on domestic abuse working quite well as a metaphor and framing device. One of the first instances of these “recovered memories” happens when Billie is in the shower and has the sudden sensation and visual of being drowned by an unseen assailant. Up until this point in the film, there is a bit of a psychosexual thriller vibe, but we start to tip into full-on horror the more we start to see Alex’s true self and the terrifying nature of this relationship unfold. — KKU

8. Black Swan (2010)

dir. Darren Aronofsky

Even after many repeat viewings, I watch Black Swan in a perpetual state of distress. I know Nina will sacrifice her entire self — her body and her mind — for the pursuit of the leading role in her company’s production of Swan Lake. I know she will unravel. I know the unraveling will lead to seeing things that aren’t really there, to a fracturing of reality. And yet even though I know what’s coming, the specific touchpoints of this unraveling scare me.

I’m not usually into horror that relies on jumpscares, but I think what works about the way they’re deployed in Black Swan is that they’re so seamlessly integrated into the visual and emotional storytelling of the movie while still operating as interruptions to reality. There’s a sense that something menacing lurks at the edges of every frame in Black Swan.

The best of all the jarring moments in the movie comes when Nina is in the bathtub. Bathtubs are often the site of terrifying moments in horror — the classic shot from A Nightmare on Elm Street is the crème de la crème. In a bathtub, you’re naked and vulnerable, relaxed which also means you’re on low alert. Black Swan makes its bathtub sequence explicitly sensual and frightening. Nina begins masturbating and lowers herself all the way underwater. But when a drop of blood falls into the tub and she looks up, she’s met with a smiling figure who looks an awful lot like herself. It works on a lot of levels. The bathtub setting, the use of sound, the doppelgänger. Seeing one’s self is a particularly effective source of uncanny horror in psychological thrillers like this one. And in Black Swan, Nina’s sexuality is tightly wound to her obsession with rising to the top. This scene distills that entanglement into its most basic parts. For a jumpscare, it’s bloody complex. — KKU

7. Bad Things (2023)

dir. Stewart Thorndike

The Shining is one of my favorite movies of all time, and Stewart Thorndike’s queer reimagining of its narrative for Bad Things makes for a delightful and daring horror movie that’s familiar and surprising in equal measure. Drew said it best in her review, which is what first convinced me to move it to the top of my viewing list: “This is not the easy Hollywood update of putting a few queer characters into a franchise reboot — this is deep textual analysis and fuckery presented with a sharpness of filmmaking worthy of its influences.”

Ruthie inherits a hotel and is convinced by her girlfriend Cal to run it, Ruthie’s history of infidelity weighing greatly over the relationship. Surely taking over a small town hotel is just what every struggling relationship needs. Surely nothing will go wrong here.

What’s fun and ultimately so scary about Thorndike’s approach is that things go wrong slowly, slowly, then in an onslaught. The atmospheric horror is wonderful. On a long weekend at the hotel with their friend and Cal’s ex Maddie as well as Maddie’s on/off girlfriend Fran, the group encounter strange hauntings.

The first real injection of horror comes when Fran begins seeing figures in the hotel, starting with a bunch of people in the dining hall eating breakfast. They all look up at her silently when she enters. “Sometimes, you can’t feel your fingers,” a little girl says, her fingers detached on the table. When Fran stumbles out, the room empties, making it clear she has just seen not just one but a whole bunch of ghosts. From there, things just get progressively weirder, but the group also turns on Fran, accusing her of lying, which of course only heightens the horror. — KKU

6. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021)

dir. Jane Schoenbrun

Jane Schoenbrun’s understated, unnerving We’re All Going to the World’s Fair is difficult to define in terms of horror and in terms of queerness and transness. It’s a movie about the depths and dangers of loneliness. It’s a movie about the nebulous and, well, difficult to define predatory behavior of adult men toward young people in all corners of the internet.

There isn’t explicit abuse at the hands of Michael J. Rogers’ JLB toward Anna Cobb’s Casey, but that feels weird to say. Not all abuse — especially that takes place online — is straightforward. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair contends with the ambiguity and slipperiness of the internet in so many ways. It starts with Casey joining an online horror game whose purpose and rules are impossible to grasp throughout. Does Casey think she’s playing a game or think she’s immersed in something real, undergoing actual transformations? There’s never a clear answer, which Schoenbrun pulls off dazzlingly well.

The only person we really get to see Casey interact with in the entire movie is JLB, a man who is similarly lonely but also a grown ass adult. The movie disturbs in strange, potent bursts, the most affecting of which is a sequence where JLB narrates over a video Casey filmed and posted of herself sleeping. He paused on a frame in which she appears to wake up and her face distorts into that of a nightmarish demon. The image itself is scary, a bit Exorcist-esque. There’s a found footage element to it, too. But there are layers to the horror beyond a creepy face that really deepen it — and make it fucking scary. JLB analyzing Casey’s sleep so closely — even in the context of a game, even though Casey has willingly shared this video for strangers to see — feels threatening and ominous.

Most queer people in my life — myself included — had inappropriate interactions with adults online before we were out. What makes it harder to talk about — and ultimately scarier — is that we sought these connections out, were hungry for them. Validation online felt affirming. Even (especially?) when that validation came from adults. But does that make us complicit in these inappropriate relationships? No. We were kids; they were adults. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair is brilliant in the way it taps into these complexities, never portraying JLB as a monster. It shows that the internet can be a place that’s lifesaving at the same time as it’s harmful. — KKU

5. Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker (1981)

dir. William Asher

Famous for being an early sympathetic portrayal of a gay character, this absolutely batshit 80s horror movie is really so much more. There is not just a gay character; there are two. And their queerness isn’t secondary but essential to the movie and its critique of homophobia, police violence, and the presumed innocence of white women.

Despite the title — eventually changed to the equally obtuse Night Warning — Butcher Baker is not about a butcher or a baker. It’s about Cheryl (Susan Tyrell), a woman obsessed with her nephew Billy (Jimmy McNichol). She’s been his primary caregiver since his parents died in a suspicious accident, and she is terrified by the possibility of him going off to college with a basketball scholarship. Tyrell gives one of the best horror villain performances I’ve ever seen. She makes Annie Wilkes seem well-adjusted. When Cheryl kills a TV repairman after he refuses her sexual advances, her guilt should be obvious. Her role in Billy’s parents deaths should be obvious. Instead, the police blame Billy’s gay basketball coach, Tom (Steve Eastin). It turns out the TV repairman was Tom’s partner, and the police decide Billy must have been in the center of a love triangle and Cheryl’s only crime is that she’s covering for her nephew. This is so obviously incorrect. The police don’t care.

As Tom faces continued harassment amid his grief, Billy falls ill. Cheryl’s need for control has caused her to go full Munchausen by proxy. Billy is suspicious and recruits his girlfriend Julia (Julia Duffy) to distract Cheryl while he snoops around. Cheryl screams at Julia to get out. When Julia doesn’t comply, Cheryl takes out a slab of meat and a meat tenderizer. She smacks the meat harder and harder as she grows agitated before finally bursting into tears. She tells Julia that she had a boyfriend once, she understands. She seems to have softened — it’s not convincing. Billy is still upstairs snooping. She asks Julia to get something from the fridge and SMACK she hits Julia in the head with the meat tenderizer. It’s blocked by the open fridge, but we don’t need to see it — the terror is in Tyrell’s face. And the knowledge that Billy is running out of time.

This is a story where the gay basketball coach is the hero. His love for Billy is selfless and appropriate, while “aunt” Cheryl’s is obsessive and violent. The movie asks: What perversions are actually dangerous? What perversions are criminalized? — Drew

4. Heavenly Creatures (1994)

dir. Peter Jackson

I’m pretty sure Heavenly Creatures was the first queer movie I ever watched. We can thank Peter Jackson and a childhood Lord of the Rings obsession for that one. It’s an appropriate introduction since film history has long been fixated on gay murderers. It’s an appropriate introduction because this film is so tied to childhood imagination.

Heavenly Creatures recounts the true story of Juliet Hulme (Kate Winslet) and Pauline Parker (Autostraddle fave Melanie Lynskey), two teen girls who developed an obsessive “friendship” that culminated in the murder of Parker’s mother. While Parker’s darkness and Hulme’s sinister manipulation are apparent from the film’s beginning, it’s hard not to be won over by the world of imagination they create together. The adults around them are so suffocating and in each other they find queer love, queer escape. As we root for them to defy their parents and be together, it’s easy to forget that the film begins with them running and screaming covered in blood. Jackson has placed us so confidently in Pauline’s perspective that even as they plot the murder, the gravity of this action isn’t felt. Until, of course, they do it.

Jackson may be best known for Middle Earth, but he got his start making ultraviolent horror comedies like Bad Taste and Braindead. This shows that brutality — but none of the comedy. The beautiful music and slow motion shots of the girls in the woods give way to the harshest reality. The thuds and splats of the brick. Pauline’s mother’s moans and screams. The blood. So much blood. The film cuts back into the girls’ fantasy space but the terror doesn’t subside. And the final shot is all reality: Pauline, alone, screaming, covered in blood. — Drew

3. Mulholland Drive (2001)

dir. David Lynch

While he’s rarely labeled a horror director, nobody scares me like David Lynch. Ever since I watched Eraserhead as a precocious 11 year old, the uncanny of his sounds and images have unsettled me more than straightforward horror.

To me, Mulholland Drive is Lynch’s masterpiece — and not just because it’s his gayest. It is his greatest combination of surrealism and grounded, tight storytelling. For a two and a half hour film with several apparent non sequiturs, it’s impressive how every scene feeds into the next, every moment feels essential. It all builds up to the horrifying end.

The first two hours of the film are about the wide-eyed Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), an aspiring actress new to LA and filled with possibility. When she encounters the amnesiac — and babely — Rita (Laura Harring), she helps her with an untouchable eagerness. This story continues to unravel, punctuated by scenes of other random characters, most notably a cuckolded director who might want Betty for a part.

This is all a dream, a fantasy, an invention of a woman named Diane as she grapples with her failure, her depression, her guilt. She has invented a world where she is a promising actress and her ex-girlfriend Camilla is a damsel in distress, where Camilla’s new fiancé is pathetic. Everyone we’ve met is someone else in reality — a reality where Diane has hired a hitman to kill Camilla.

Late at night, Diane stares at the blue key that signifies the hitman has done the job. The sound rumbles. A loud knock is heard. An old couple we met earlier in the film seems to be crawling under the gap of the door. We hear them laughing. More knocking. Screams. Knocking. Laughter. Screams. The old couple chases Diane into her bedroom where she takes out a gun and shoots herself in the head.

The lie of possibility, the faux kindness. This is what the couple represents. Diane is a woman — like so many women — killed by Hollywood. A city of dreams. A city of nightmares. — Drew

2. Good Manners (2017)

dir. Juliana Rojas and Marco Dutra

Good Manners is a Frankenstein’s monster of a film in the way it stitches together so many genres and themes to yield something staggering and, sure, grotesque but also beautiful. It’s a wholly original werewolf movie that centers queer motherhood. The love story in its first act is predicated on precarious power dynamics but also is the kind of messy, real relationship I love to watch in any film regardless of genre. A whirlwind, complicated romance that’s sexy but also laced with a foreboding sense that something is about to go very wrong. And after the first act, it becomes a movie about a mother’s love. Good Manners feels like several movies, and yet it also is impeccably well paced and balanced.

The first act concludes with wealthy Ana dying while delivering her werewolf baby, because it turns out delivering a werewolf baby when you are a human woman with a human body is extremely, um, unpleasant. It’s quintessential, good body horror, but it’s also devastating because it happens while her nanny and new lover Clara is in the adjacent room trying to call a doctor for help. We see the horror in-scene, and Clara sees its aftermath.

Clara’s used to working as a caretaker, and even though her relationship with Ana began from a place of being paid to care for her, it grew way beyond that. The fact that she cannot care for her in this crucial, terrifying moment conveys a suffocating hopelessness.

By the time she enters the room, Ana is already gone. Her body sits there, ripped apart, and Clara’s life rips into pieces too. It’s forever changed not only by this violent, nightmarish loss but by the new werewolf son she unexpectedly gains. Ana’s death is complicated by the fact that it happens not at the hands of some plainly villainous monster but rather an infant creature who has no control over the way he enters the world. There’s no one for Clara to fight in this moment, no one to run from. Just a baby, alone and likely as fear-stricken as her. — KKU

1. The Other Side of the Underneath (1972)

dir. Jane Arden

When we started working on this list, nothing stood out as number one. And then we watched Jane Arden’s The Other Side of the Underneath.

This is a movie that had been on my radar since I put together the all time lesbian movie list. It was in my working doc under “possible entries – unavailable.” So much queer art is outsider art; so much outsider art is harder to find. In fact, this film was practically unavailable worldwide until BFI restored and released it in the UK in 2009. But it was still largely unavailable in the US until Shudder recently put together a series celebrating the tenth anniversary of Kier-La Janisse’s House of Psychotic Women.

Kayla and I will reflect on the queer films of David Lynch and Peter Jackson and Alfred Hitchcock in a different way than Bravo and Shudder. But the greatest joys of this list were the discoveries. The greatest joy was clicking play on this masterpiece by a radical artist and having no idea the twisted queer magic I was about to witness.

Jane Arden was a feminist writer, theatremaker, and filmmaker who struggled with mental illness and campaigned against the psychiatric treatments of her time. This film is about a group of young women experiencing that treatment and it oscillates between that horror and surrealism likely inspired by the headspace of the film’s protagonist with schizophrenia.

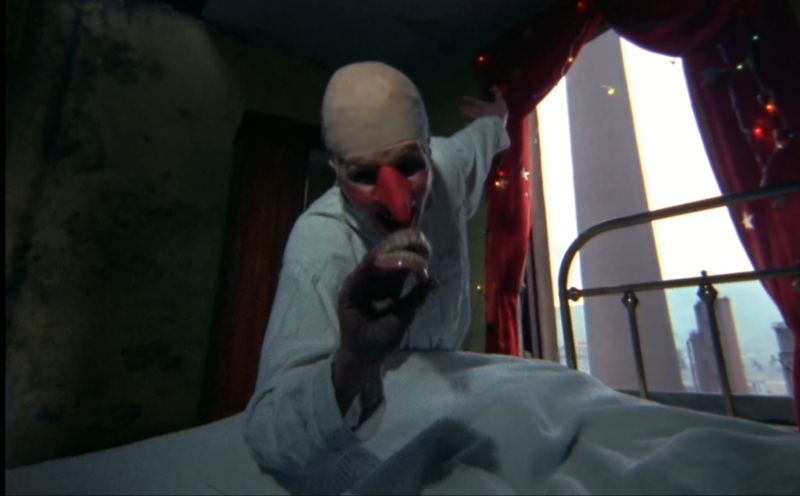

It is a film filled with striking moments and surprising horrors. But the sequence that first made me realize the special nature of this film happens about ten minutes in. The young woman is lying in bed next to a nurse. Then we cut to another young woman furiously playing cello as she chants, “Multiply.” The music increases as the main young woman stabs her bed with a knife. The cellist screams on the soundtrack and then quiet. The woman in bed is no longer next to a nurse but lying in the bed of a sort of dream space. A little girl looks at a pair of dentures in a dirty cup. Then we meet her: Meg the Peg.

An arlecchino-inspired nightmare clown bursts into a point of view shot from the bed. “Meg the Peg can read your thoughts little girl!” she exclaims while clacking together dentures. She has a poorly fitted bald cap and a sharp fake red nose. Her eyes are open almost as wide as her gaping mouth. We cut back to the young woman who looks shockingly calm. And then back to the girl. The clown reappears in this frame and reaches for these other dentures. “Mine!” she shrieks. She carries on for quite some time saying, “Mine” and when we cut back to the young woman in a wide shot there’s a sheep in her bed. “Not right,” she says as she shakes her head. Yeah, I’ll say.

The clown’s antics continue, increasing in their terror, but also becoming oddly sexual. The young woman seems to be under her spell, enamored with the act. She kicks off her sheets to reveal blood and the calm remains. The clown disappears and her dresser shakes open. Another young woman is inside clattering unnaturally around until she falls forward on the bed. The young woman cackles with glee.

This film was based on Arden’s stage production, A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets, and Witches. Even as some fight for assimilation, it would do us well to remember that whether or not we see ourselves this way, that is how much of the world still sees us. Horror has long been a genre of reclamation, a genre of expression. There is nothing in horror as scary as our most radical queer artists being lost to time.

The Other Side of the Underneath is terrifying. This scene is terrifying. But when it ended, like the good little freak I am, all I could do was cackle with glee. — Drew

HORROR IS SO GAY is Autostraddle’s annual celebration of queer horror.

“To me, Mulholland Drive is Lynch’s masterpiece.” – Yes, thank you. This.

Drew and Kayla teaming up is always a good thing.

Two of my favs – Heavenly Creatures and Mulholland Dr. Can’t even tell you how many times I’ve watched both. Love all the women in these films but Kate Winslet will always have my heart. Lol.

#25 watch it and then read Carmen Maria Machado on it

“like The L Word if it didn’t take six seasons for them to start killing each other”

a perfect clause

Great list! Love to see some favorites as well as some films to add to my watch list.

Also this is so well-put: “The goal cannot be palatability. It should always be dimensionality.” YES.

Beautiful description of the bathtub scene in Black Swan. This is a great list with lots of new stuff for me to check out.

“The Untamed” (2016) definitely belongs on this list too. It blends cosmic horror with sexual discovery, and is one of my favorites! https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/the_untamed_2017

The Other Side… is currently to be found on youtube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=z106qEo8Etw

I am extremely excited to delve into the movies on this list that I haven’t seen! Especially the other side of the underneath and butcher, baker nightmare maker. I also appreciate that several of the movies at the top of the list might not be abject horror, but the moments included in them are horrifying.

Do you know where I can watch Tom at the Farm (2013)? (United States)