Lulú Martinez is fond of cats and lists her political views as “queer liberation.” A Chicago resident, she immigrated to the U.S. from her hometown of Tlalnepantla, Mexico when she was 3 years old. Last week, for the first time in 20 years, Martinez was able to visit her family and the place of her birth. But she had to self-deport to do it.

Out of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants currently living in the United States, as many as 267,000 are LGBTQ-identified. Many of them, like Martinez and I, came when they were young and have had to navigate daily life without the equal opportunity to work, go to school or obtain government-sanctioned ID. Having established roots and community in the U.S., the decision to leave in pursuit of the ability to travel and move at free will is not an easy one, and is exacerbated by the fact that many who do choose to leave while out of status are barred from returning to the U.S. for a period of three to ten years.

Aware of this risk, Martinez, along with undocumented activists Marco Saavedra and Lizbeth Mateo, decided to challenge this dynamic between borders and home. After they crossed the border a few weeks ago and spent time with grandparents and cousins they had only known through pictures and phone calls, they joined five other undocumented people who had either been deported or self-deported to Mexico, effectively separating from their own family members who still lived in the U.S. Known collectively as the Dream 8, they publicly attempted to cross the border back into the U.S. seeking humanitarian parole, to reiterate to families who have known the pain of separation from an arbitrary wall that their fight did not have to end at deportation. This act of civil disobedience, the riskiest in a long line of infiltrating detention centers and sit-ins in Congressional offices, aims to put the power – and arguably, the right – to migrate back into the hands of those who are directly affected by the U.S.’s long and troubled history of immigration.

In a last minute, Hollywood-like twist, moments before the eight were to cross the border back, a young woman approached them, explaining that she had heard of their plan and had traveled to the border town of Nogales to join them. She wanted the chance to go back to Phoenix, Arizona, where she had grown up and had graduated from high school, but was forced to return to Mexico two years ago due to the hostile atmosphere of racial profiling created by SB 1070. And thus, the Dream 8 became the Dream 9. Surrounded by chanting supporters on both sides of the border wall, the nine presented their application for parole, were subsequently arrested and detained and are now being held on U.S. soil — a first, if potentially temporary, victory.

Martinez and her eight fellow ruckus-raisers are currently being held at Eloy Detention Center in Arizona, a for-profit privately owned facility notorious for its dire conditions, detainee suicides and its omission of at least ten detainee deaths from public record. CCA (Corrections Corporation of America), the largest private prison contractor in the U.S., brings in over $1 billion in annual revenue, and houses over 80,000 immigrants in its detention centers on any given day — more inmates than housed by the states of New York and New Jersey, combined. They are paid by the government per detainee, per day (at a reported average of $122 for each immigrant) and charge $2 – $5 a minute for phone calls. The growth of private centers like Eloy are fueled by the record-breaking level of deportations under the Obama administration, standing currently at a total 1.5 million deported immigrants since 2009, more than any other president in U.S. history.

Buried in these numbers and statistics are the personal stories of detainees, many of whom are needlessly imprisoned, for months and sometimes years, for things like driving without a license (that they are often not even able to obtain) or being caught in a workplace raid. The Dream 9, expecting and secretly hoping they would be detained, are now sporting on-trend green jumpsuits and organizing cases from the inside, hoping to shed light and push for the release of those who should never have been detained, per the administration’s own amended guidelines, in the first place.

This action stands proudly on the shoulders of almost 15 years of grassroots organizing by affected immigrants in the United States. With Martinez, it also weaves threads of queer visibility, inclusion and liberation into the narrative fabric that continues to be constructed around migrant rights. On March 10, 2010 in Chicago, she was one of many to come out as undocumented during the immigrant rights’ movement’s first National Coming Out Day. Borrowing notes from the playbook of Harvey Milk and others in the LGBT movement, the importance to give ourselves visibility, to reject the shame and taboo of living without papers and to bring ourselves out of the shadows, even without the protective blanket of legislation, was recognized. The rallying cry of this movement, Undocumented and Unafraid, was born.

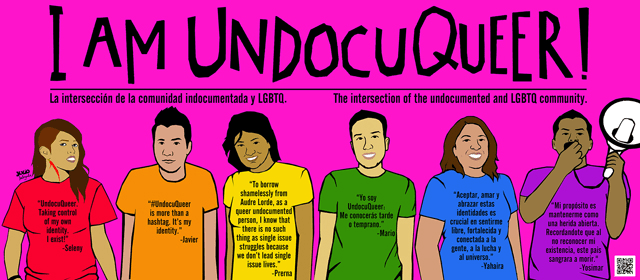

Since then, it has also been recognized that many grassroots undocumented youth groups were created, lead and supported by a strong contingent of queer immigrants who identified, among other things, as trans*, butch, bois, lesbians, gay, and jot@s. This sub-group, who have coined a new identity of the UndocuQueer, have led an intentional push for inclusion: of the unique struggles and perspectives of LGBTQ immigrants in the often white-centric gay rights movement and of the corresponding (and just as legitimate) struggles and perspectives of LGBTQ people in the assimilationist rhetoric of the immigrant rights movement. Undocuqueers have also shed understanding on the need for sensitivity in environments where they often have to come out twice — as undocumented and as LGBTQ.

A phrase that often arises in this movement is “ni de aqui, ni de alla,” (neither from here nor there), and it speaks to the ability we seek as queer immigrants to define home as we choose, whether in a geographic sense, within our communities, or a gendered sense, within our bodies. Transnational actions such as this point to how we, as affected people, can continue to queer the narrative around migration, by rejecting the constructs of borders and citizenship and by affirming our right to simultaneously inhabit multiple homes. Through fighting to bring them home, we also fight to reconcile the multiple parts of our community that remain invisible, strewn across deserts over unmarked graves and stuffed into too-tight suitcases straining from the impossible task of simply surviving the journey.

this is really informative and interesting, thank you

i liked this a lot.

excellent! thank you for this piece, ningun humano es ilegal! <3 <3 <3

I watched the live feed from the border on Monday when they tried to cross and got arrested. I thank God I can’t imagine being as brave as they are.

Check out all the videos here: http://www.ustream.tv/new/search?q=bring+them+home

Contact your representatives and signing petitions for their release here: http://action.dreamactivist.org/bringthemhome/

this is so fucking rad. thanks for this piece, kemi!

^agreeing with everything above. This is a great article!

This is an incredible article, thanks so much for writing it and including it on autostraddle!

I don’t live in north America, but have been following with awe the activism around the DREAM act etc… Just so inspiring and such brave people.

Thanks again for the article, great read :)

Thank you so much for writing this.

Thank you all for listening!

This is really interesting, and I’m glad to see more original pieces on Autostraddle on immigration and prisons, because I usually get my fix of that through Things I Read That I Love.

I want to see more stuff like this on autostraddle! Super awesome!