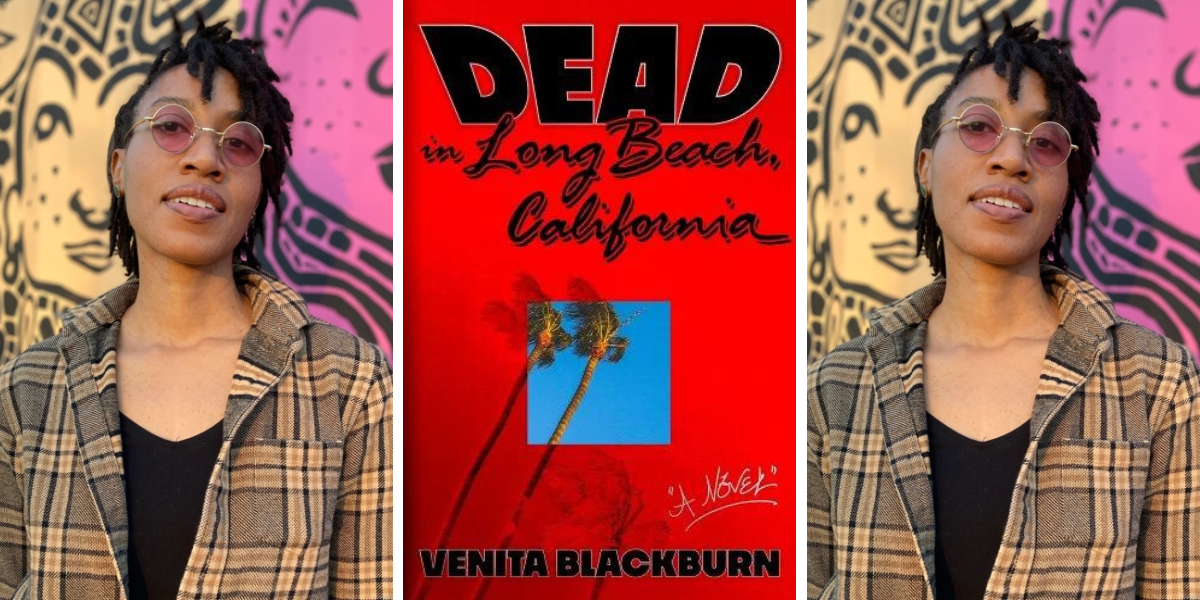

feature image photo of Venita Blackburn by Virginia Barnes

Sometimes someone is like, here, read this novel about grief, and you’re like yeah, I know about grief novels, and you read it, and it’s devastating and heartwarming in all the ways a grief novel purports to be, and you walk away saying yes, it’s all very clear, that was most definitely a grief novel. Other times someone is like, here, read this novel about grief, and you’re like yeah, I know about grief novels, and then that novel is Dead in Long Beach, California by Venita Blackburn. How to describe this genre-defying, mind-altering, utterly arresting story about complicated families and fierce love and the losses that accumulate over the course of a life? Saeed Jones said, “Your wig is going to fall off no matter what you do,” and that’s just the truth.

Dead in Long Beach, California follows graphic novelist Coral, who thinks she’s stopping by her younger brother’s apartment for a visit and instead finds herself dealing with the aftermath of his suicide. In the haze of grief that settles after his body is taken away, Coral, understandably, finds herself unable to cope — so she takes her brother’s phone and begins to assume his digital presence. I’m talking text his daughter, make plans with his maybe-girlfriend, make the man an Instagram kind of assume his digital presence. This novel is, of course, soul-crushing. It’s also, sometimes, quite funny. It’s the story of one woman’s mental breakdown, it’s a lesbian sci-fi saga, and it’s a tender exploration of how humans struggle to process unimaginable loss. It’s upsetting and absurd and, at times, you don’t know where it’s going to take you, but it always sets you down right where you need to be. It’s a grief novel, sure, but that’s not even the half of it.

Listen, I could go on and on about the rollercoaster that is Dead in Long Beach, California, but this is not a review, and I was lucky enough to sit down with Venita and talk all things debut novel — so I’ll let her tell you the rest herself.

Author’s Note: The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Daven McQueen: Starting out with a classic first question, what was your inspiration for this book? Where did you come up with the idea?

Venita Blackburn: Well, I had the idea for the interior parts of the book far earlier. The original title was “Lesbian Assassins at the End of the World.” That was sort of the big vision. I was kind of going to do this wild, epic kind of high fantasy sci-fi sort of thing with a small tether to modern existence and set in California in different time periods and all that kind of jazz. But I also tend to look into a lot of my older work and there’s always something that I’m not done with — concepts, characters that are still nagging me and rubbing against my psyche. I have to go back and sort of figure out what it is that’s still bugging me. There’s a few stories from my second collection, How to Wrestle a Girl, about dysfunctional maternal situations and femininity and sexuality, and I carried a little bit of that over into Dead in Long Beach. Then I started to deal with why I was trying to do this high fantasy sci-fi kind of world that is so far away from the things I know. I found it’s because of these profound senses of loss, this world of transformation and this feeling that we cannot go back to what we used to be and to the relationships we used to have.

I wrote most of the book during the pandemic, this huge moment in time — and we’re still in it. We’re still in this transformative state where we have to make a lot of big choices about who we’re going to be and what things we’re going to carry forward from our past into our future. If we’re going to try to cut a lot of them off, what will that mean? Who will we be after that? And there’s also the sense of denial about the nature of our history, about who we are as individuals — capable of terror, great terror, and also great love and compassion. And this idea that we haven’t quite navigated that sense of our own selves in a lot of ways. That’s when I started to go into the real heart of the story, the frame story, that’s set in the real world with a character who’s lost her brother and is unable to psychologically process that. That became what I knew was going to be the biggest story. I did a lot of trimming of the big fantasy in order to make room for what I would call a horror story.

It’s a little funny, but it is a tragedy. It is emotionally taxing to think about it, let alone to have to produce it over and over again on the page. I started to realize that I was distracting myself with the other story because it was fun and weird and sexy. That’s why the story wasn’t coming out.

DM: What you just said, describing the book as a horror — that’s something that really struck me as I was reading. It’s like, the hairs on the back of my neck are standing up, there’s this sense of claustrophobia. At the same time, like you said, you do have this sci-fi story interwoven throughout and this narrative voice that is non-traditional and extra-human. I’m wondering how you’ve come to think about the genre of this book, if there’s a way that you feel like you define it.

VB: The only kinds of genres I tend to think about is sort of, is it nonfiction? Is it poetry? Is it fiction? How close to reality are we going to get? Within the different breakdowns of fiction, I have no idea what this book is. Is it literary fiction? Is it fantasy? Is it sci-fi? It is this kind of strange anomaly in terms of genre. I would definitely call it a horror story, but that’s just because this is what I would classify as horror. I grew up watching traditional horror movies with my mom when I was a kid, very young, like five or six years old. She was just into it. She loved ghost stories and psychological trauma stories, and now those movies have a sense of comfort for me. Men behaving like monsters, dressed up in costumes, that’s almost cute to me versus, you know, what I think is truly terrifying. The truly terrifying things are the stuff that we can’t see. The stuff that’s going on internally, the breakdown of the mind, the loss of people that you love. The stuff that happens in real life, that’s horrifying.

DM: I’m also a big horror fan, and I’ve been watching them since I was really young, so a lot of the traditional scares feel sort of…

VB: Goofy?

DM: Yeah, goofy!

VB: They’re goofy. They’re silly! And I love that you mentioned claustrophobia as an element of horror and isolation. This particular character is dealing with that kind of internal claustrophobia. The world seems very big to her because of the life she’s living, tangential to fame in Southern California, which has that vast feeling. We don’t do a lot of high rises here, so the landscape is kind of low to the ground, too. You can sort of see the expanse of nature; things feel kind of open. But on the inside, she’s not connected to human beings in a way that she ever will be again. She’s gone through this complete separation and she’s unable to speak it. And that creates that other layer of claustrophobia where she is kind of bound in her own brain. No one else is in there with her except for the voice, which isn’t her own voice. That collective hive, that’s her only comfort.

DM: I do want to talk a little bit more about this hive voice. The first-person plural is so rarely used in fiction, and I’m curious about how you decided to use it.

VB: I love the first-person plural. I think it’s a beautiful voice with a sense of authority over the content. That’s sort of the trick that it brings. Every POV has its own little tricks. The first person is limited to just one person’s brain, comes out of their voice and their perceptions. You can’t go beyond it. You don’t have that sort of god-like aerial view of the world. The first-person plural allows you to get that, but also to have that god-like sense of everything else, because you always have more than one, the “we.” I think it’s just magical, the way that authority immediately happens. I call it the sort of natural sense of peer review built into the voice. It’s also a sense of community and a sense of belonging that’s built into the voice. And that’s exactly the thing that this character has lost, right? Her family is now broken, and her sense of self is broken too. She needs something that’s going to keep her tethered. In this moment, because she is so isolated, all she has is her own brain. This is the voice that she’s actually created for her own artistic purposes, and it’s the one she falls back on in order to navigate her way through this terrifying moment in her own life.

DM: It is really interesting the way that the voice does have this sort of collective feeling. There’s some level of warmth and community there, but we’re looking in on Coral who is so increasingly isolated and inside her own brain. I think that contrast really contributes to the sense of horror.

VB: Yeah, and I tried to create a sense of momentum as well, going forward, where it’s getting worse. You know, she’s got to make progressively worse choices. That’s just the rule. That’s the fiction part of things. Things’ve got to get worse and worse and worse and worse until they can’t anymore. But the voice has a sort of steady attitude about it all. Even if it’s terrible, that voice says, no, it’s beautiful. It’s beautiful and horrifying. Let us practice it. Let us, you know, revel in the marvel of this maliciousness. It’s this juxtaposition of all of the good and the bad and the things that make up humanity and make up who we become in these crisis moments, too. The beauty and the violence, the sadness and the celebration.

DM: Because of the voice, as much as the book is really focused on what’s going on inside Coral’s head and this experience of her life unraveling after her brother’s death, there is also this broader unpacking of what people are and why they make the choices they do. There is sort of this sense of doom around that, but at the same time the collective voice is, saying, “Everything’s going to be okay.” You saying you wrote this during the pandemic makes a lot of sense; I can see a lot of those feelings present there. I feel like it’s also really speaking to the present political moments that we’re in and the increasing sense of doom that a lot of people are feeling. But at the same time, the voice is engaging with some level of hope. I’m curious about how you think about that hope-doom balance in the book and how that connects to the world and humanity more broadly.

VB: I don’t believe in hope. But I’m also optimistic. I have that kind of ancient Greek philosophy about hope, that it arrests man’s despair. It makes you stuck. It’s when you’re in a crisis moment, and instead of doing anything, you’re just sort of hoping that things work. It’s also the thing you say to somebody when you’re not going to do absolutely anything to help them. You know, they tell you that they’re sick and you’re like, “Oh, I hope you get better.” I try to remove the word “hope” as much as possible from my lexicon because it has that feeling to me of inaction. I want to encourage people to, if you see something terrible in your life, in your community, that you make an effort to change it. You don’t want hope, you want action. You want reason. You want logic and purpose. You have to have all of those things, no matter what happens in the end.

That’s sort of my personal philosophy of things. And I guess it filters into that voice as well, because technically the end has already happened. People didn’t make it, according to the voice. It’s speaking beyond humanity, and it’s doing so in a way that’s sort of honoring their presence. It’s a child loving their grandparents and honoring their ancestors, even though really, the voice is not even human. They’re just sort of data. And I think that’s kind of connected too to where we are, where the last thing that we might leave is just a record of ourselves, just our data. We’re generating a lot of it all the time, to the point where it becomes so messy and chaotic that we don’t even know how to recognize ourselves amongst all of these little echoes that we’re leaving all over the digital spaces we inhabit. I’m kind of obsessed with that idea, but not that it’s going to destroy us. I don’t think our technology will be the end of us. If anything takes us out, it’s going to be us. But I don’t even think that will happen, you know — I think we will endure. We’re a surviving sort of species. We have thumbs! We keep creating new ways for us to prosper and to survive. But we keep forgetting a lot of things. We almost encourage ourselves to not think about our mistakes in our history. That’s the thing that can keep us from progressing and keep us arrested in our own despair and suffering. Because we don’t even know how we got there, because we forgot, because we didn’t teach it to our children. We didn’t make that record. Human beings are always this way. We always make a mess. We always clean it up. We’re violent to each other. We’re violent to our children, to ourselves. And then we are suddenly capable of such compassion and gifts of love without question. That’s the thing that’s hard to record. We forget that really easily as well, especially in our age of presentation, where if you’re if you’re not online protesting for something, then you don’t believe in it. It’s only real if we see it in these small squares of digital light. That’s not the true human self either. We have to keep reminding ourselves of all the different levels and states of existence that we’re constantly cycling through all the time in order to just be.

I don’t believe in hope. But I’m also optimistic. I have that kind of ancient Greek philosophy about hope, that it arrests man’s despair. It makes you stuck.

DM: I absolutely love that perspective. I think so much of what we’re fed is just this very black and white idea of like, either you have hope for the future and it’s just so misguided or we’re doomed, everyone’s going to die, climate apocalypse in the next, like, 15 years. That, I think, removes humanity from the equation in a way. This book has a sort of reverence for humanity and what we’re capable of that I feel like you don’t see that often. I really saw that kind of undergirding the whole story.

VB: I appreciate that you saw that. And that’s also kind of how I think. I’ve been called chronically unbothered or something along those lines. I don’t know where it comes from; I haven’t always been that way. I’ve gone through my cycles of being humbled by the world, being humbled by personal loss, and having to really build a lot of good habits around self-reflection and things like that. I have a lot of causes that really affect me mentally. Education is one, homelessness is another, violence against women is another. And then all of the other things across the globe that are all connected to those same things, connected to property, to extreme wealth gaps. That all really make me mad. It tends to disturb my unbotheredness because I can see how much suffering trickles down from all of those things. I think about that kind of perpetual nature of it, how we just have these bright moments of enlightenment on occasion, and then they break. You think you have a generation of peace, then you go a little further around the world and realize, oh, there’s an apocalypse happening just there. All that keeps cycling around itself. The only thing that we can really control is ourselves, you know, save who you can save. We have to remember to stop and go talk to each other in real life, in real time and make eye contact and move through the air with each other and walk this planet because that’s the real thing of life. You have that duty to care for yourself and care for your community. That will be the best thing we can never leave behind.

DM: Absolutely. And I think this book is kind of instructive, in a way. Or, well — the issues Coral is dealing with in the aftermath of this loss, the lack of connection and separating herself from the world, we’re seeing in her how things can go wrong and, in some ways, how not to act. As I was reading, there were moments where I was like, oh my god, stop doing that. But at the same time, I was like, I understand how this feels like the only thing that she can control. She’s trying to maintain a hold on anything possible. And…I don’t know if I have a question out of that.

VB: Well, that’s kind of what I was talking about with the juxtaposition of the good and the bad, because it starts off where Coral just needs a little bit more time, right? She’s mad at the world, she’s mad at men, she’s mad at all the things that have put her into this position where she has to clean up for people around her. But then she says, I’m going to make it stop. I want to make everything calm and peaceful and not let anybody suffer for a while. She almost gives people a gift of withholding the trauma of the loss. Then it turns into this act of cruelty where she’s actually setting them up for higher expectations. She’s sort of reaching into their futures and creating the impossible with these different relationships her brother has. And that’s part of the violence. Her anger starts to manifest in other ways. She becomes manipulative, she becomes toxic, she starts to go off into the world in progressively worse ways.

Yes, it is not an instruction manual. There is no instruction manual for grieving. When it hits you, it just hits you, and you’re just going to walk through the way it does. I say in the acknowledgments that this is just one shape of grief. It will take its own form for everyone. It’s an amorphous experience and there’s no right or wrong, truly. People just, you know, we do things that have consequences and all we can manage is what happens in the before and the after. And that’s the reality. There are no solutions offered here. In some of the earlier stages of the editorial process, my editor mentioned that we don’t get a note or anything from Coral’s brother. We don’t really talk about why the suicide happens. And I said, well, that’s not the book. That’s not the point here. This is not a book about how to get over it or prevent these things from happening. These things happen and sometimes we’re here right in the middle of the crack of devastation, the crack of grief, the crack of suffering, and this is what it can look like. That was the only promise I made, that we’re going to be right there. I’m not going to give you any reasons, I’m not going to give you any solutions, but here we are.

DM: And we definitely were right there the whole time. I know your two short story collections also dealt a lot with grief and families grieving. What draws you to write about grief?

VB: You know, there is this phrase — I wonder if it came out of a Disney cartoon or something — but it’s the saying that every story is a love story. It probably is not from a Disney cartoon. But I agree with that. I think every story is a love story, but also every story is a grief story. You know, it’s about loss. It’s about goodbyes and transformation and losing things of the self. I think every story is really invested in all of those things. There are these deep connections, this deep need and desire to feel like you belong and like someone cares about you without question. Every character is trying to find that somehow. But they’re also navigating this sense of deep loss of something. It can be very small, but it’s usually on that bead of grief somewhere. I think this story falls into both. It is both a love story and a grief story. The collective voice, the thing that is holding Coral in place, is profoundly in love with humanity, and that is essential because it’s also a reflection of this deep love Coral has for her family, for her brother, for all of the people that she has been losing. I think that’s just part of my view of people, so all of my stories are going to have that. It’s going to have loss. It’s going to have love. Otherwise I wouldn’t be writing about people, in my own mind.

But I also write about this weird period of adolescence, when you’re changing into yourself as a person, figuring out your own sexuality and how you’re going to present yourself to the world. I call it adolescence, but a lot of us go through adolescence for like, 30 years. Like, I used to wear really cute, like, body dresses. I had this Victoria’s secret type style; I was a super tall, weird, kind of, you know, gangly thing. Now I dress more like a dad on vacation. I got a grandpa chic sort of thing going. And I’ve never been more myself than I am now. And that’s just the surface level. That’s still part of giving up the thing and losing the thing you thought you had. That too is built into the love and the grief and the goodbyes and the hellos.

DM: I think that’s particularly true of queerness, this idea that when you come out you basically go through a second puberty. We kind of see that with Coral’s character, the ways she’s evolved through time. We see her discovering her sexuality, her first girlfriend and all these relationships, up to the dates she goes on after her brother’s death.

VB: Those are so weird. Oh my god.

DM: Yeah, I was like, oh my god. Leave the bowling alley!

We have to remember to stop and go talk to each other in real life, in real time and make eye contact and move through the air with each other and walk this planet because that’s the real thing of life. You have that duty to care for yourself and care for your community. That will be the best thing we can never leave behind.

VB: The one thing she does that I really love is that she did not order pizza for her coworkers. I was like, I support that. I support you leaving them in this state of hunger and just walking away. Of all the bad choices she made, I did like that one.

DM: I loved that moment. When she sticks her head back in and is like, it’s on the way. There is this uncomfortable delight in all of the ways that she’s making these choices and deceiving people. You’re like, oh, god, but you’re also kind of like, that’s kind of fun.

VB: I like that you saw it that way. I do have to say that when I wrote a lot of these parts, I was not in a good place. I was in the weeds, you know, kind of delirious, tapping into the rhythm of the sounds and the voice, the scenes, and the metaphors and all that kind of stuff, cycling through that sort of writer moment. Then months later, I would go back to read them and I would just crack up. I was like, oh my god, I am insane. It was not funny on the first write through. But once you experience it in a different state, it has this other effect. And I kind of like that. I like that it could be this dark place and this light place.

DM: A lot of your work is really focused on Southern California, and I know you grew up in Compton and in the LA area. I also grew up around LA, so there is a lot of familiarity to me in this book. I’m really curious about the way you portray Los Angeles — you capture a lot of the reality of it, but there’s also this sort of dreamlike quality where it doesn’t it doesn’t feel quite real. It’s like LA in a dream. How were you thinking about the sense of place as you were writing this?

VB: I’ve heard it described that way a lot, the sort of the dreamscape of LA. And I agree with that, because isn’t LA kind of like this dream? It means a lot of things to people, even from around the world. They have this idea of it. And I think that’s more LA than the real thing. The idea that this collective vision of this place is actually much better. People think of LA as a sort of nice, clean place, you know, hopes and dreams or whatever, celebrities and whatnot. But it’s actually really nasty. It’s super old and it can be dangerous, like any big city can be. I remember once I went to a conference in downtown LA, around the Staples Center. It’s got all the usual stuff, all the sort of semi-fancy, semi-pretentious chain restaurants packed with people. The food is just like, whatever, but you know, the sidewalks are clean and it’s bright and there’s palm trees or whatever, and a nice, beautiful breeze comes through so certain times you might even also smell the ocean a little bit. You all have these different kinds of sensory experiences going on and people look stylish, their clothes are bright and colorful. Then I turned a corner and a man was there bleeding out of the side of his body. He had just been stabbed. He had wandered off from close to Skid Row and was sort of yelling, you know, I got stabbed. No one did anything. I think a security guard popped out eventually and ushered him back to that area. And I remember standing there thinking, like, look at this. We think everything is okay, everything is working out. We’ve painted this picture, and then the reality wanders back over and no one does anything. I didn’t do anything. It’s all happening within a very few seconds.

That’s LA to me. It’s a mess. It’s this sort of construction of self, but there’s something gruesome underneath. There’s people just struggling. There’s tons of debt. There’s people trying to pick their dreams off the floor. But there’s still the idea of LA pulsing all the time around them. You’re just going to work and living your life, but it’s still right up against this extreme wealth and possibility for fame.

DM: Zooming out a little bit, there’s a lot going on in this book. The genre is kind of undefinable. There’s so much complexity in the narration and the character and her experiences. What is the process of writing a book like this? How do you keep it all straight in your head and have a sense of where it begins and where it ends?

VB: That is so hard, and this is why I’m just terrified of having to write another novel. I really appreciated those early times when I was writing stories and nobody cared if I was ever going to be a writer. It was sort of just me by myself doing this thing. I could make anything happen. With this book, because it’s so long, I hadn’t written a novel like this since I was a grad student. And even that one, I reduced it down to a few pages and published that. I’m like, ah, I don’t know. I don’t know what’s going to happen here. I can’t keep track of everything in my brain the way I’m used to, because in a flash fiction story, it’s two pages. I can look at the top anytime I want to, I can look at the bottom anytime I want to, I can keep track of all the objects that I’m manipulating.

This time, I’ve got so many little pieces all over the place. I felt sort of disoriented a lot of times. That was before I started to do a lot of the revision parts and the cutting and the reducing and sort of finding the things that I really wanted to keep versus the things that I was just sort of writing out of a desperate need to be elsewhere for whatever reason. I think there’s a novelist trick where you don’t think about the beginnings and the ends. All you think about is the task at hand on any given day. So if I’m writing about, you know, depression and ice cream or whatever it is, that’s it. My whole task for the day is to explore those two things for this character in this moment. And I don’t have to leave it. I don’t have to worry about trying to make it match up to anything. I have to trust my outline, trust that it’s going to be fine, and just devote the time to the language there on the page.

DM: Yeah, that’s such a mood. I know this book is just about to come out, but I’m curious what you’re looking to next. What are you writing towards, post this book?

VB: I am working on another novel, gosh darn it. But I’m also writing short stories simultaneously. People are asking me for some of the new stuff, but I’m holding on to them. Kind of seeing what I want to do with it. I’m starting to think more in terms of whole books now than I used to. Kind of the entire shape of a collection, entire shape of a novel before committing to the wholehearted writing of it. I am working on a novel that is going to be sort of historical horror, supernatural fiction. It’s an extension of a story I already wrote, a long, serialized story that came out in the Gagosian. It’s called Memoir of a Poltergeist. It’s about an ancient ghost that possesses this black lesbian in the Reconstruction period of the American South. And it too is a love story. It too is a grief story. But it’s got these different layers of the characters’ psychology. You’ve got the ghost, you’ve got the actual woman, you’ve got the community, there’s a kidnapping and a murder — it’s all crazy.

DM: It really feels like your work occupies its own cinematic universe of like, I don’t even know how it would be defined. But I’m excited for the next installment of it. Is there anything I didn’t ask you that you want to say about the book or your process or anything?

VB: I just want to always encourage people to be kind to each other, to have compassion, to choose compassion over violence whenever possible. And it’s going to be hard, and nobody listens to me, but still give it a shot. Do the good work, do the thing, take care of people. Don’t expect anything in return, not a single thing. And now you’re alive.

I first heard of/read Venita Blackburn in one of Kayla’s short fiction playlists, and then I bought How to Wrestle a Girl (and really liked it!) and now there’s this fantastic interview! Gonna have to pick this book up.

“that it arrests man’s despair” – what a phrase

omg that makes me SO HAPPY that you initially heard of venita via short fiction playlists! i need to bring those back

Fully support bringing the short fiction playlists back

Daven, thank you so much for this interview. It feels like such a privilege to read it. This part from Venita REALLY got me: “But we keep forgetting a lot of things. We almost encourage ourselves to not think about our mistakes in our history. That’s the thing that can keep us from progressing and keep us arrested in our own despair and suffering. Because we don’t even know how we got there, because we forgot, because we didn’t teach it to our children. We didn’t make that record. Human beings are always this way. We always make a mess. We always clean it up.”