Welcome to Underwear Week, a whole week dedicated to your favorite bum-hugging clothesthings. As we said many moons ago, we feel a lady is at her best when she’s not wearing pants. And while our last adventure around this neck of the woods took us only as far as boyshorts, this time around we’re exploring the vast and many-flavored land of underwear. From edible panties to hoopskirts and history, we’ve got you covered. Just like your underwear.

By A.E. and Abby

Come along, queers, and gather round for story time. We’re talking about underwear this week, and though most of what we’ve been covering has been pretty light and fun and fashion-y, we wanted to take a moment to hop in the wayback machine and talk about underwear in a historical context.

Anyone? Rocky and Bullwinkle? Mr. Peabody and Sherman? Anyone? Bueller? via Wikipedia

Did you all just fall asleep on me? I know, I know, but I promise this will be interesting. Also this is about your queer elders. Show some respect. And tuck in your shirt.

Tonight I remember the time I got busted alone, on strange turf. You’re probably wincing already, but I have to say this to you. It was the night we drove ninety miles to a bar to meet friends who never showed up. When the police raided the club we were “alone,” and the cop with the gold bars on his uniform came right over to me and told me to stand up. No wonder, I was the only he-she in the place that night.

He put his hands all over me, pulled up the band of my Jockeys and told his men to cuff me – I didn’t have three pieces of women’s clothing on….They cuffed my hands so tight behind my back I almost cried out. Then the cop unzipped his pants real slow, with a smirk on his face, and ordered me down on my knees. First I thought to myself, I can’t! Then I said out loud to myself and to you and to him, “I won’t!” I never told you this before, but something changed inside of me at that moment. I learned the difference between what I can’t do and what I refuse to do.

When I got out of the tank the next morning you were there. You bailed me out. No charges, they just kept your money. You had waited all night long in that police station…You drove us home with my head in your lap all the way, stroking my face. You ran a bath for me with sweet-smelling bubbles. You laid out a fresh pair of white BVD’s and a T-shirt for me and left me alone to wash off the first layer of shame.

Though Stone Butch Blues is a fictional account of 1950s working-class, lesbian bar culture, the “three articles of clothing” rule that Jess is arrested under for wearing men’s underwear is real. And it is much older than you might realize. This wasn’t just McCarthyism at its finest (although that did have a lot to do with it); laws outlawing cross-dressing or “masquerading as the opposite sex” actually go back to the mid-nineteenth century. Jess’s wearing of men’s clothing wasn’t just a social taboo, it was a criminal act. And it’s because of the real-life women who took enormous risks to their personal safety, and who physically fought to wear whatever undies, clothing and footwear they damn well pleased that we can have underwear week at all.

Starting in the 1840s and continuing well into the 20th century, ordinances were passed in cities making it a crime for a man or a woman to appear in public “in a dress not belonging to his or her sex.” In the nineteenth century these laws had little to do with any sort of moral outrage over men and women wearing clothes that were atypical for their sex. Homosexuality in the way that we know and understand it had yet to become part of the larger social consciousness and certainly didn’t induce the same sort of reactionary gay panic that it would later. (Omg! The gays are taking over!). Rather, the laws had far more to do with the broader changes happening with regards to industrialization and the move to more populous, urban spaces. 1

Prior to the Industrial Revolution and the resulting expansion of urban living, most people resided in small towns and villages where everybody knew everybody and everyone was all up in each other’s business all the damn time. But in some ways, living like this was good because it was simple. When you spotted someone on the street or when you needed a service rendered, you knew the person you were about to interact with. You knew if they were going to try to cheat you out of some money or if you could trust their word. Who needed the internet when you had a personal Yelp in your mindbrain? But as people moved away from towns and into cities, the dynamic changed. Suddenly they were surrounded by strangers, by unknowns. Which brings us back to these cross-dressing laws. The increasing need to rely on first impressions in order to accrue knowledge about someone’s character led to a growing anxiety about how to interpret appearances and manners in order to suss out a person’s class, background, character and, ultimately, their trustworthiness. Clothing and dress was literally a person’s public face.2 The thought that clothing might be used to mask someone’s true nature, rather than to reveal their character, was incredibly unsettling in this period.3 Thus, cross-dressing laws were less about gender policing (although that is inherently a factor), and more about trying to ensure that first impressions were as accurate and reliable as possible. By the time we get to the 1950s, however, these laws continued to be enforced almost exclusively because of a moral panic over “deviant” sexualities that would surely rip apart the very fabric of American society and turn us all into pinko commie dykes.4

I mean, I know that’s our gay agenda.

Whew. So that was some quick and dirty context for y’all. Ready to fast-forward and get back to the 1950s? Sure you are.

After WWII there was a significant migration of women who self-identified as lesbians to urban spaces. The result of which was that a bar culture began to form as bar owners realized that lesbians would pay good money for a safe space to socialize. These bars were essential in fostering a sense of community, particularly among working-class and young lesbians. The bars were also a space where women were freed from societal norms with regard to clothing and gender.5 Although WWII had made pants acceptable to be worn by women, skirts were still the norm. Pants were seen as incredibly casual – butch women in the 1950s searching for dress pants remembered that they had to get men’s trousers specially tailored because dress pants for women didn’t exist at the time – and more something that you would wear at home that out in public. But in the bars, women had the freedom to adopt a masculine presentation.

Keannie Sullivan & Tommy Vasu at Mona’s, via foundsf.org and the Epic Autostraddle Gallery

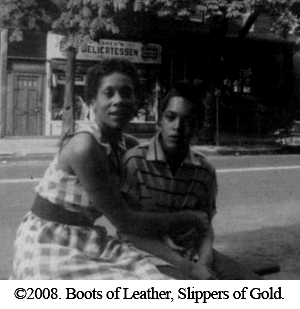

Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline D. Davis’s “Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold” is is one of the best studies of working-class, lesbian bar culture in this period. Based on interviews with 45 different women in Buffalo, NY, the work details everything from the nature of bar culture to the personal relationships these women had (both romantic and otherwise). The women interviewed describe how, unlike the 1940s when women only frequented bars on the weekend and were far more covert about wearing masculine clothing, working-class butch women went the bars most days of the week and took an immense amount of pride in their appearance.

Since they went out to bars every night, not just on weekends, they had to have appropriate butch clothes for both casual wear and for dressing up. Regulars at Bingo’s in the midfifties remember white butches wearing sport jackets, chino pants or sometimes men’s dress pants, and men’s shirts – button-downs, western shirts, or tuxedo shirts with ties on the weekend. When out during the week, they would dress more casually in shirts and chinos. Among younger white bar dykes in the late fifties, blue jeans and t-shirts became popular, particularly during the week….Black studs adopted a more formal look even on weeknights, wearing starched white shirts with formal collars and dark dress pants whenever they went out…none of these butches, white or black, ever carried purses.

The wearing of masculine clothing was about more than simply playing the butch role within the bars; it was a very obvious and public “fuck you” to the societal norms that butches and studs found oppressive. Butch women remember distinctly that their everyday uniform of jeans and white t-shirts was an unmistakable signal of queerness. And underwear (or lack thereof) often played an essential role. One woman explained, “butches, we’ve always worn T-shirts. That was our thing, right? And most of the time why did we wear T-shirts, because we didn’t wear a bra….We just threw them away and put on T-shirts. And boy, when you wore a T-shirt – Wow! They didn’t look to see where your tits were. Oh, you have a T-shirt! We were the Original.” For other women, binding was the way to go. Whereas disregarding a bra entirely was an in-your-face “Yeah, I’m a woman in a t-shirt and jeans. Come at me, bro,” those women who chose to bind cultivated a more ambiguous appearance. But an ambiguous appearance also meant uncertain safety. Though some women could, and did, pass and could use their appearance as a cover and protection when they were on the streets, the times that they weren’t read as male were extremely dangerous because they couldn’t possibly be anything other than queer.

Even if someone was passing, the wearing (and buying) of masculine clothing didn’t come without its risks. When purchasing clothes, many women made up a story about purchasing something for their husband or boyfriend. Those who didn’t remember that shopping for clothes meant anxiety over being exposed and facing ridicule. But worse than the embarrassment was the (often violent) harassment by both the police and straight men. Many women mentioned the “three articles of clothing” rule in their interviews with Kennedy and Davis (though some claim it was actually two articles), and one woman remembered her very near miss with arrest because of this.

I’ve had the police walk up to me and say, “Get out of the car.” I’m drivin’. They say get out of the car; and I get out. And they say, “What kind of shoes you got on? You got on men’s shoes?” And I say, “No, I got on women’s shoes.” I got on some basket-weave women’s shoes. And he say, “Well you damn lucky”‘ ‘Cause everything else I had on were men’s–shirts, pants. At that time when they pick you up, if you didn’t have two garments that belong to a woman you could go to jail…It would really just be an inconvenience….It would give them the opportunity to whack the shit out of you.

via Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold and The Epic Autostraddle Gallery

Street harassment and fights were also a routine occurrence, and it was an essential part of the butch ethos to take on any challenge that came their way. It was understood that you had to be strong, and that you stood up to a challenge. “You would naturally get up and fight the guy…we all did it at that time. And we’d knock them on their ass, and if one couldn’t do it we’d all help….But you never failed, or you tried not to….You were there, you were gay, you were queer and you were masculine.” Engaging in physical fights was about more than proving toughness or saving face though, it was the only way for these women to make a space for themselves.

I think that’s the only way we could act then. We just didn’t have any ground except what we found for. Especially like Iris and Sandy for instance, on the street people just stared at them. I would see people’s reactions, I would see them to me if I was alone too, but I would see reactions when I was with my friends, and the only safe place was in a gay bar, or in your own, if you had your own apartment. Out on the street you were fair game. – Toni

Sick of hiding, and tired of only accepting the meager scraps that society gave to them, butch women physically fought for the right to be visible. They risked arrests, assaults and beatings to wear the clothes they wanted to wear. Without them we might not be able to have underwear week. The risks they took, and the momentum they built by fighting back against police harassment, eventually culminating in the Stonewall riots and the start of the gay liberation movement, are the reason that Autostraddle can tell you what the best boxer briefs in all the land are. They’re the reason we can even sell you You Do You boybriefs without being concerned that you’ll be arrested for wearing them. Without being particularly political themselves, and simply by living their lives the truest way that they knew, these women put things in motion.

So walk proudly into Uniqlo and buy some boy briefs – you probably don’t have to make an excuse to the cashier about buying them for your boyfriend for fear of legal action. Courts stopped prosecuting cross-dressing cases in 1974, at least in New York State. And the ACLU says in states/counties/cities that still do have cross-dressing laws on the books, anyone arrested under that law should fight it in court because the law will likely be ruled unconstitutional. And say a big thank you to Dear Sweet Lesbian Jesus that we had some foremothers willing to fight the fights that would eventually ensure our legal gender presentation and would lead us down the path of choosing some bum-cuddling soft cotton with which to swaddle our gay buttocks, regardless of “sex-appropriateness.”

1 N.B. There is so so much history here, and so many interesting things I (Abby, the historian person) could talk to you guys about! I wish I had time and space to talk to you about cross-dressing in vaudeville and how it was seen as incredibly wholesome, family-friendly entertainment for much of the nineteenth century, and then the changes that occurred to make it well…not so wholesomely received anymore. And I want to tell you guys all about the history of romantic friendships and the deeply intimate relationships women cultivated with other women, and that was socially acceptable and highly encouraged! But, alas, this is but a simple piece about cross-dressing laws and underwear, and so I have to give you the quick and dirty version of history. BUT if this is a thing you want to learn more about I highly suggest starting with Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers by Lillian Faderman, and then falling down the history rabbit hole from there.

2 There was a massive uptick in the number of etiquette books published in this period, all aimed at the newly formed (and rising) middle classes, as well as those in the working classes who were beginning to have both time and money for leisure. Not surprisingly, the cultivation of one’s appearance and manners were the primary focus of these manuals in an attempt to help people navigate and be successful in this rapidly changing society.

3 It’s not a queer history by any means, but if you’re interested in this period I (Abby, the historian person) highly recommend Karen Halttunen’s Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870. It’s a really great study that delves into these anxieties surrounding appearances and sincerity in the mid-nineteenth century.

4 Interestingly enough, there was a moment after the end of WWII where many lesbians thought that they had entered a brand new (read: open and accepting) world for women loving women. Lisa Ben, the editor of a short-lived post-war lesbian periodical, Vice Versa (the first of its kind in America – it’s a zine! Well, kinda.), wrote a euphoric article in 1947 claiming, “Never before have circumstances and conditions been so suitable for those of lesbians tendencies.” (Faderman, 129)

5 Even though the bars didn’t conform to societal norms, they did create their own–the butch/femme dynamic was an incredibly strict divide and, with very few exceptions, women had to conform to one or the other in order to participate in bar culture.

Recommended Reading

If you’re interested in reading more about this period (because there is so much more, you guys! And we know you’re interested because, lezbehonest, you’ve gone past the footnotes) here are some good books:

Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America, by Lillian Faderman

A Desired Past: A Short History of Same-Sex Love in America, by Leila J. Rupp

I’ll be straight with you guys, this is not the best book out there; it gives, to my mind, an overly rosy view of queer history, but what it does well is give an overview of this history in an immensely readable way. This is a good introductory book.

Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870, by Karen Halttunen

Stone Butch Blues, by Leslie Feinberg

This is fiction, but if you’re looking for something to give you a feel for this period it’s really pretty excellent.

Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community, by Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline D. Davis

It can be hard to get your hands on a copy of this book – I bought my copy used through Amazon – but if you can it is so, so worth your time. Most college libraries will probably have a copy if you don’t want to buy it.

The Persistent Desire: A Butch-Femme Reader, edited by Joan Nestle

This is another one that can be hard to find – used book sellers and libraries are your friends.

i looooooove this post

Fantastic post. More like this please! I love love love the history of us.

this is so awesome and well-researched! thank you abby & ali. now i’ve gotta hit the library / used bookstores and gather all the books i’ll be reading for the next few weeks (months?)…

Months. Def months. Wait till you see how heavy Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold is. And I mean that both in actual physical weight and content saturation.

Really enjoyed this post. Definitely a good reminder for how lucky I am today. Thanks for the recommended reading as well. Looking forward to learning more about the history.

Great post! Thanks for the recommended readings, and Thanks to all the brave women who paved the way!!!

Thanks for this great article. I especially love reading about butch history, and this was wonderfully comprehensive and full of care.

This article is so good. I am fascinated by lesbian history, and hearing real people’s experiences of it. I wish my AP world history class was like this. But then I guess it would be AP herstory, and that wouldn’t happen. Too bad.

This made my day. Pouring one out for all the trailblazing, badass homos who went before us.

So so good. I’d love to hear more about the things you said you didn’t have enough time/space for.

Ever since reading Audre Lorde’s “Zami” I find myself endlessly fascinated by 1950s US lesbian bar culture. Thank you so much for this piece, I can’t wait until grad school is OVER so I can get my hands on all those queer books.

This was a fascinating article. I’ll have to put all those books on my reading list, but can I lend my vote to having more of these sorts of columns? Herstory month last year was some of the best stuff this site has produced.

Dear Sweet Lesbian Jesus,

Thank you.

Signed,

Dear Sweet Lesbian Child.

PS: Some of these real life story quotes also appear in a book I just started and love: A Critical Introduction to Gender Theory by Nikki Sullivan

I’m a little sad that trans women weren’t mentioned more, seeing as Stonewall /was/…

And I’m sure queer women of the trans persuasion might have interesting stories to tell about history and underwear.

There was the Compton’s Cafeteria riot in San Francisco’s Tenderloin started by trans women. It started when a police officer grabbed a trans woman to take her to jail for “public indecency” and she refused. I read about in “MTF Transgender Activism in the Tenderloin and Beyond” in a Queer Cultures and Society class.

Great article!