This is Autostraddle’s “How To Survive A Post(?)-COVID World” series. In some areas, COVID restrictions are lifting, but regardless of how “post”-COVID some of our individual worlds might feel, a pandemic and its lasting effects rage on. These writers are sharing their struggles and practical knowledge to help readers survive, heal and thrive in 2021.

I. Dreaming

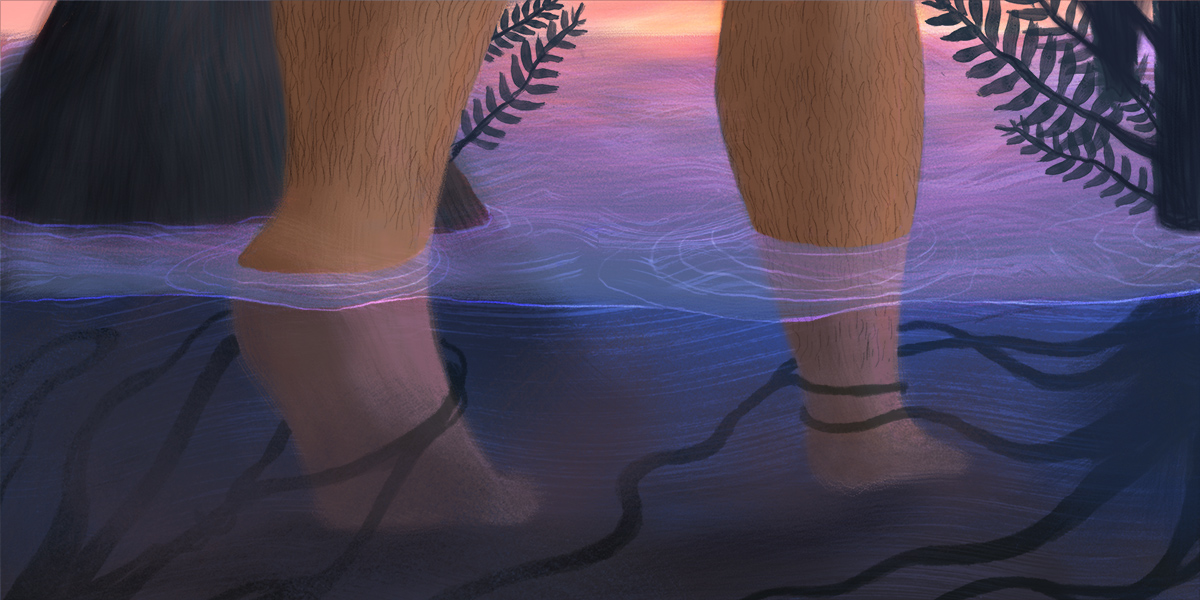

In the dream, I am running breathlessly through the woods at daybreak. There is nothing chasing me and I am running, which assures me this is a dream. As my legs slash through the brush, thin branches cut my shins, and dew on grass washes the blood away in a lullabilic rhythm that soothes me just enough to keep going. If there are animals watching my fat Black body rumble through the woods, they do not make themselves known. There are no crickets chirping, no rustling of leaves, no rivers running. The woods let my breath take up all of our shared space.

I run until the grass becomes dirt, until the dirt becomes rock, until the rock becomes nothing. And I stop. I sit down right at the edge, my thick thighs folded criss-cross applesauce as if I am back in primary school on Ms. Hood’s reading carpet. This is the second sign that this is a dream. My thick thighs have not criss-crossed since primary school, but in this dream — I run, I breathe, I cross my legs and sit on the edge of cliffs as if to say, “This here is mine — this life, this moment.” When I wake, the cliff fades back into my bed and the valley beneath it is just chilled hardwood.

I tap my wife. I hate waking her in the middle of the night. She will be at her computer screen teaching science to black squares hours before I even exit the bedroom in the morning.

“I can’t sleep.”

She stirs and tells me to come and lay in her arms. I stay long enough to hear her fall asleep again.

The night is long with nothing to fill it, a marathon to nowhere. At night, all I hear is the sound of my rotating fan and our breathing: my wife’s, the dog’s, and my own, labored with grief and exhaustion. I go to the bathroom and check my phone. Swipe down, click, swipe down, switch app, click, swipe down, refresh. I repeat until my legs fall asleep and I will them awake by standing and staring at my reflection in the mirror. I am tired of running.

II. Running

When I was in high school, I was a four-year varsity letterman in track and field — heavy on the field. I was a mediocre shot-putter at best and mostly just showed up because I liked sports and was too fat to make the basketball team (there is more running involved in shot put than advertised). Twenty years later, my thighs burn just thinking about the mile we ran to warm up. I always dreamt of being a distance runner, long and fast.

“Keep pumping your arms!” The coach would yell at the distance kids as they trained around the track. “When you are tired, keep pumping your arms and your legs will know what to do!”

I spent the first nine months of the pandemic running full stop. I had just quit a horrible job to focus full-time on my studies and consult more; to be “free.” Terrified, I kept running. Most days, I was afraid to leave my work to get fresh air. The only steps I took covered the distance between my bed, couch, and desk. Yet, where my body wasn’t moving, my dreams were active. I created a collective. I built learning experiences, communities, and programs for folks to stay connected as the world fell apart. I facilitated open spaces, scheduled Zoom dates, read, researched, applied to PhD programs, worked, fucked, and tweeted in order to keep myself alive. If you keep pumping your arms, your legs will know what to do even when the world is crumbling around you.

When it got too hard to run in our 600-square-foot home in Boston, I ran to Vermont to breathe. The mountains met me with openness that let me go, go, go until I could no longer feel the ground or my legs, into a numbness with a beautiful backdrop of greens, blues, and the reds and oranges of the most picturesque sunsets.

III. Sitting

Fate meets you regardless of how fast you run.

My dad died sometime between lunch and bedtime on my wife’s birthday in the second worst year of the decade. At 32, I was an orphan and a seasoned runner. Up to and through my father’s death, I spent my life running, afraid of what might happen when I stopped to rest. Afraid that my community, my job, this world might deem me worthless or invisible without my contributions.

Ain’t you tired of running, baby? my soul asked.

I did not respond. Grieving while the world is grieving is the loneliest lonely I’ve ever met. When my mama died, folks flocked to hold space for me and my healing. During the pandemic, most of my circle was just treading water and I was my own buoy, gasping for air on days the sun shines. It was just enough for me to keep going.

We buried my father’s body. For the first month after, I spent most of my days in bed. My grief, a new, unexpected lover, spooned me tightly as she took everything I could muster. Each morning, I ate oatmeal from a glass measuring cup and spent my days staring at empty Google Docs and measuring my water intake. I did not work. I did not respond to other people’s texts about him — about how sad they were, about how they were thinking about me. The honeymoon phase of grief is just as all-consuming as new love. It envelopes your being and latches onto your heart, reminding you that you are — were — loved and treasured and desired by someone so fiercely that the mere absence of them makes you crumble.

Instead of running from this grief, I chose to sit in it. I was supposed to spend six months writing and instead I spent six months crying, sleeping, and watching the same romantic comedies with all-white casts and predictable endings. White rom-coms are like fantasy movies for folks like me: comforting in a “this is completely unrealistic and yet wouldn’t it be nice if everything also worked out” kind of way.

At the end of Eat, Pray, Love, Julia Roberts, who has somehow afforded a year abroad despite a costly divorce, tells Javier Bardem she loves him. “I decided on my word,” she says. “Attraversiamo. It means ‘let’s cross over.’”

Sixteen months into a pandemic and six months after my father’s death, I wonder what it means to cross over into what comes next.

IV. Being

On Saturday nights in the mountains, my wife and I drive forty three miles south to a restaurant where everyone knows our name. We are the fat, interracial, queer, vegan couple that drives from a different state to order a sandwich and french fries and call it fine dining. We drive past white folks’ country homes surrounded by empty land with “keep out” signs — as if anyone might think of traipsing through the tick-infested tall grass to enjoy an evening picnic. White people are always worried about someone else taking what they took.

Mura Masa’s “What If I Go” blasts through the speakers of our Subaru. “Wherever you go / I’m going with you, babe!” Bonzai sings. The bass is just thick enough to hold my grief and sorrow; to make me bounce and smile as we drive through more darkness I knew I could — then yell.

A bear lumbers in front of our car, across the street, and traipses through the tick-infested tall grass like he didn’t see that “no trespassing” sign them white folks posted. My wife shrills in half-excitement, half-shock. We check off “see a bear” on our “before we leave the mountains” bingo card and keep driving.

In the woods, we can see stars that are hidden by the clouds, buildings, and smog in cities. When we drive after sunset, I count stars to the beat and get lost in thoughts and rhythms.

“Can I ask you a question?” I ask my wife. She is still reeling from the thrill of seeing the bear, but can hear the promise of tears in my voice.

“Of course,” she says.

“Do you think my dad is with my mom?” I ask. My grandma raised me to believe in heaven, but death, trauma, and homophobia have exhausted most of the faith I had left.

“Absolutely. Scientific law says that energy cannot be created nor destroyed. So I imagine that their souls have found each other because that connection is forever,” she responds. My wife is a scientist; sometimes her healing comes from knowing that explanations exist for the most unfathomable grief.

Mura Massa’s track stops and another begins, with my silent tears as accompaniment. Like a broken record, I play my wife’s response on a loop in my head, bringing me equal parts peace and relief – not just in my grief, but in choosing to not to run this time — in choosing to invest fully in my own healing and rest.

V. Choosing

It’s confession time: I never ran the entire warm-up, even when I said I did. I usually jog-walked two laps and called it quits. I think my coaches knew back then what I know now. It’s not about the distance but about knowing yourself enough to push through when necessary, and rest when you need it.

If what my wife (and Albert Einstein) says about energy is right, I’d like to imagine that queer energy (and connection) is the same way, especially for folks like me – queer, Black, nonbinary folks forever seeking home and a soft place to land. That even when we choose ourselves, we do so with the love of a community that will forever exist, even amidst isolation, fracture, and heartbreak.

And ain’t that freedom? That we can fly, knowing the ground ain’t going nowhere; that we can heal, rest, and love ourselves without fearing the loss of what once was; that despite everything that happens — we will always be.

I’m tired of running. You go ahead, baby. I’ll get there when I’m ready.

We — this community, our love, this moment — is forever.

Wherever you go, I’m going with you, babe.

Art by Hannah Mumby

so many aha moments and feelings that were sooo beautifully articulated. shea always finds a way to clearly communicate raw moments of their emotional experience so well, and often times all i can do is laugh and cry and reread and cry again. thank you for sharing your journey and simply for being ❤️

Goodness this is beautiful, thank you for sharing <3

Stunning, every time. Thank you, Shea <3

I’m 31. My father died in January, and I loved him and he loved me very much. I feel all of this so hard.

wow, I’ve bookmarked this essay. it was everything I needed to read and more. Thanks for sharing, Shea

This is so beautiful! Thank you for writing it!

Thanks for sharing amazing information keep posting.

I had to stop reading this when it first posted – I was too close out from the loss of my own father. Came back today when I saw it linked on shea’s twitter. What a gorgeous meditation on grief! shea, you are such a soulful and gifted writer. I understand your decision to leave this site, but I am so sad to see you go. Wishing you well as you move forward – may you find home and a soft place to land.