Tania De Rozario and I met when we were sticking stickers that said “I JAM to AWARE” onto tiny pots of – wait for it – jam(!) for a fundraiser. I did not know then that this was the same Tania that my partner had been raving about for a bit – they’d crossed paths at the Singapore Arts Festival – but it didn’t take long for me to be similarly awed by her and her work.

De Rozario is an artist, writer and curator interested in issues of gender and sexuality. She is an alumna of Hedgebrook (U.S.) and Sangam House (India), is an Associate Artist with The Substation (Singapore), and freelances as an art-writer and art-educator. This December, she will be at The Unifiedfield (Spain) working on a new visual arts project.

De Rozario and I are both from Singapore, where we commiserate over the various ridiculous doings of our government (to her, as an artist, to me, working for The Man, and to both of us as unapologetic queermos). Her first book, Tender Delirium, was published this year and so I jumped at the chance to interview her about her writing, art and community organising.

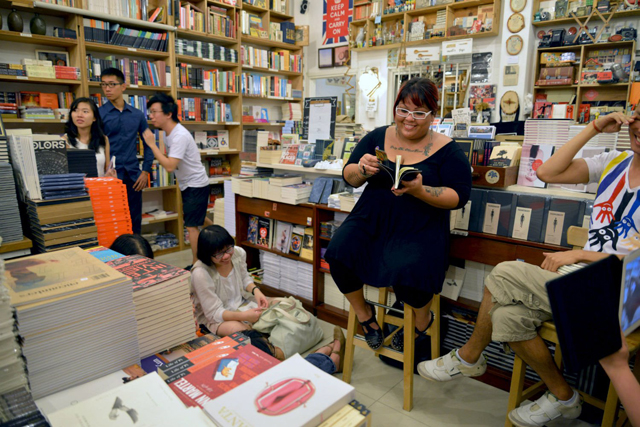

The launch of Tender Delirium at BooksActually, a small independent bookstore

via Robin Ann Rheaume

On (Queer) Art, Visibility and Censorship

The Media Development Authority (MDA) is active in regulating content production and distribution in the country. Free-to-air TV, for example, bars any productions that “promote or justify a homosexual lifestyle” or the broadcasting of “music associated with drugs, alternative lifestyles (e.g. homosexuality) or the worship of the occult.” However, “non-exploitative and non-explicit depictions of sexual activity between two persons of the same gender may be considered for [a] R21 [rating].”

At the opening of IndigNation 2013, in an effort to not just centre your opinions, you presented a bunch of other people’s answers to, “What are your concerns with regard to the future of LGBT art-makers and art-content in Singapore?” But now this is all you! So what say you?

I am concerned that one day, we will all master how to get around laws/policies so well, that we will stop fighting them and start accepting them as status quo. I am concerned about the number of queer people from the creative community who have upped and left the country because of the trickle-down effects of 377A [the colonial era law barring sexual relations between consenting adult men] on their practice and their lives. I am concerned about young queer people, and queer people with minimal access, who do not see themselves represented in the media, on television and in film, because their lives have been deemed “inappropriate.” I am concerned about how this affects both their views of themselves as well as attitudes towards them.

You’ve been very vocal about content regulation – or less euphemistically, censorship – even as it is one of those issues that frequently slides off the radar. As a queer artist, and especially as one who writes about sex, has censorship affected your work and if so, how?

To be perfectly honest, I have not personally experienced much censorship when it comes to my writing. As yet. I suspect that the general consensus is that poetry is safe because most Singaporeans don’t read it. The bulk of censorship in Singapore, I think, is dedicated to film and media, because these are seen as mediums that are more accessible.

There was an instance in which one of my stories was used as an English comprehension passage for secondary school students, and the paragraph alluding to sexuality was edited out. I was pretty appalled. I mean, seriously? You 1. take my work without permission, 2. cut shit out 3. without permission and 4. think yourself fit to be an educator? But other than that, there’s been no censorship of my writing (that I know of).

Demonstrating civil obedience

via Zarina Muhammad

Plenty of artists and non-artists alike are content to accept content regulation and censorship as “just the way things are,” while others find ways to work around or avoid it instead of agitating against it. What do you think about this?

I don’t think that “working around” censorship is necessarily a bad thing as opposed to agitating against it. I think both are necessary. It really depends on the end-goal of any particular project, and what that work being in the public sphere can or is supposed to achieve. It’s important to remember that in Singapore, you’re expected to adhere to licensing and classification rules for every other random thing, including art exhibitions, and that not doing so can result in punishment. Sometimes, “working around” censorship just means knowing how to fill in an application form without lying but also without alarming authorities.

I could cite a crude example: when the director of The Human Centipede was looking for backers, he told potential funders that the film was a horror movie about a surgeon who likes to sew people together… what he didn’t say was that he liked to sew people together mouth-to-anus so that one person’s shit would flow into another person’s digestive tract.

There is value in this strategy. Once any work hits the public sphere, offending people and alarming powers-that-be becomes a natural reality. But it’s there that the agitation starts, I think. If queer content is going to get berated, censored, restricted to only particular audiences or have funding withdrawn from it because of stupid policies, let it be done in the public eye so that it can be fought in the public eye and so that it does not go undocumented. It’s hard to advocate against censorship when so much of it goes unseen.

At the #FreeMyInternet rally, protesting a website licensing regime

via Robin Ann Rheaume

How do you think a culture of censorship (i.e. not only formal policies/laws but the way we adjust our behaviours and expectations because of them) affects the way we create and interact with art in Singapore? Are there specific implications for queer artists and community?

Based on the existing classification system, the implications clearly are that our lives do not make for appropriate or acceptable subject matter for general audiences when it comes to art-making. As a 19-year-old friend of mine put particularly eloquently, “If my life were a film, I would not be old enough to see it.” And this in turn implies that our lives are not appropriate or acceptable in general, doesn’t it? People’s responses to art embodying queer subject matter are just an extension of their responses to queerness in general.

When Brokeback Mountain hit public cinemas, I woke up one morning to a local DJ going on about how the film was “wrong” and “unnatural,” and that the only reason it was being shown as that women like watching men make out the same way men like watching women make out. (‘Cause you know, everything in this world revolves around the logic of one person’s male heterosexual desire.)

The government would like to think that policies like retaining 377A for “symbolic” purposes is a live-and-let-live situation. It is not. It enables the discriminatory media policies that our authorities hold so dear and it enables bigotry by permitting one side of the “gay debate” to transpire in the public sphere while censoring or limiting the other side. Could this DJ’s on-air companion have argued with him without being seen to be “promoting” homosexuality and therefore contravening existing media policy and putting her job at risk? I can’t say for sure, but probably not.

On Activism and Community Organising

De Rozario is the co-founder of EtiquetteSG, a multidisciplinary showcase of art, writing and film created by and about women. Addressing gender as a subject of discourse, it uses art as a tool to create spaces within which critical and creative conversations can take place. She has also worked on independent projects with various activist groups such as AWARE (gender equality advocacy group), IndigNation (annual LGBTQ pride month) and Sayoni (queer women community and advocacy group).

How does your art interact with your activism?

I’ve never really considered the possibility that I might be an activist until recently, when someone asked whether I’d be one of the activists reading in an upcoming production. I was like, “Am I an activist?” Her response was, “You’re an art activist.” Until now, I’m not sure what that means.

I think a lot about and occasionally volunteer my time towards issues related to gender and sexuality. Every now and then, I write an angry piece about 377A that gets published on Fridae. Sometimes, I curate exhibitions that raise small amounts of money for NPOs. But essentially, my practice does not revolve around activism; it revolves around issues that I am interested in and care about.

The cast of a production of The Vagina Monologues, organised by EtiquetteSG and Sayoni

via Gwen Kwan / EtiquetteSG

You’re currently working on a project linking activism and visual arts in post-2000 Singapore. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

Making Trouble is the project I’m doing for The Substation’s Associate Artist-and-Researcher-in-Residence Programme. The project aims at investigating, articulating and documenting the intersections between visual art and socio-cultural activism in Singapore since the year 2000. The entire process is supposed to serve as a qualitative study of individuals who occupy space in both the visual arts community as well as civil society, and whose work is motivated by affecting change.

I’d like to map a visible network of practitioners, events and spaces to create a timeline of events that highlight engagements between civil society and the visual arts. I am also hoping to document the histories and roles of spaces that have either been established or hacked in order to create spaces in which non-dominant discourse, creative or otherwise, can or has transpired.

Tania De Rozario with co-organiser Ng Yi-Sheng promoting IndigNation at Pink Dot SG

On Writing

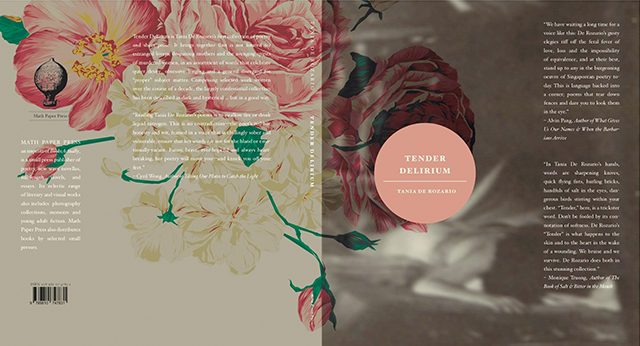

Tender Delirium is De Rozario’s first collection of poetry and short prose. It brings together (but is not limited to) estranged lovers, despairing mothers and the avenging spirits of murdered women, in an assortment of words that celebrate queer desire, obsessive longing and a general disregard for “proper” subject matter. Comprising selected work written over the course of a decade, the largely confessional collection has been described as dark and hysterical … but in a good way.

I know you love animals and I do too (as I type this a very fluffy cat is sleeping on my lap), but I’m going to admit that Watching Dogs Eat, the short story in which a man is attacked by stray dogs, terrified me a little. So all I have to ask is: why?

Haha – I actually asked my editor while the collection was still a manuscript whether he thought it should be taken out ’cause the collection was like, “heartbreak, love, heartbreak, mother-daughter relationship, sexuality, heartbreak … DOGS MANGLE PERSON’S FACE … heartbreak, sexuality…”

That story is actually a result of three situations: 1. I wrote that nearly ten years ago after moving out of a traumatic living situation that included my housemates abusing their dog and me not being able to do anything about it, despite trying. 2. At that time, I was working in an industrial estate where a group of stray mongrels lived in a bordered up plot of land next to our building. They growled at everyone who passed, but I loved them, and from my office I could see into their lot and realised that what they were guarding so fiercely was their puppies. 3. When I was working there, there was a dude who got all sleazy with me in the lift and it pissed me off.

Doesn’t it all make sense now?

On the other side of things, needless to say, The Shortest Distance pulled at my heart forever. Can we talk about long-distance relationships for a bit, if not only to make me (and I’m sure plenty of people reading this) feel better?

Oh, my. The Shortest Distance. Originally, it was a letter I’d written to my then-partner to read on the plane when she first left the country for school. We’d been together for about three years by then and were living together at the time that she left. It was subsequently made into an artist book that closes into an envelope. I hand-made a hundred of them – that’s how depressed I was – and kept the first edition, sent her the second and sent another to Jeanette Winterson. HAHAHAHA. ‘Cause you know, she’s an important part of my life, too.

Honestly, I don’t know if I have anything to say about that relationship that will make you feel better – I mean, we broke up two years after she left! Well I guess one positive thing is that we’re still friends and she’s still in what I consider to be my family circle. And of course, the cliché of “I learned a lot from that relationship blah blah blah.”

Here is a cat at the book launch to make everyone feel better.

via Robin Ann Rheaume

Some of your pieces (Walking Distance, Fifteen) refer to rather uniquely local phenomena, while others, especially those about gender, sex and sexuality, speak in more general terms. As an English writer in a publishing environment where anything outside the U.S. and U.K. becomes marked as “world literature,” how conscious are you of national (or regional, etc.) identity and context in producing art, if at all? What would you like to see in local literature and audiences?

Well, to be honest, I wasn’t really conscious of this when I was writing those stories. But I was conscious of it when I reread, edited and worked on the manuscript as a whole. For example, it took me a while to decide whether I wanted to put in a glossary of terms for words/phrases like “ah beng.” But I decided against it because I didn’t see why I should pander to expectations or laziness. When I read something and I don’t fully understand the context in which a situation occurs, or a term that is being used, I look it up.

I also think it’s quite interesting that you would think of the pieces revolving around sex, gender and sexuality as speaking “in more general terms” than the pieces that deal with our education system and life in public housing. I cannot help but feel that in Singapore, that is reversed.

If you look at narrative work that has accessed mainstream appeal among Singaporeans (especially in film), the narratives that pull at the heartstrings of “common” experience revolve very much around “heartland” experience and our education system. And of course, the narratives are still overwhelmingly Chinese, heterosexual and male. It’s almost as if the idea of any alternative experience being seen as part-and-parcel of “national identity” (if there is such a thing) would be shocking for many people here. On one hand, that’s shitty. On the other, I’m quite glad that my life experiences are not being co-opted in an effort to construct some grand narrative.

Completely agreed. What can we expect from And The Walls Come Crumbling Down, your upcoming first full-length novel?

A literary memoir that deals with three intersecting stories: a house I used to live in (which I left because it was getting eaten out by termites), my mother (whom I left after years of being subject to fundamentalist doctrine), and my relationship with the girl from The Shortest Distance (who left the country and then me). As you can see, the book is full of people leaving each other. Fun times!

via Gwen Kwan / EtiquetteSG

And to end it all on a super important note: tell us about your tattoos.

God. Stop being such a dyke. First the cat on your lap, then things pulling at your heart, then the tattoos. Next, you’re gonna wanna get together to process this conversation…

Ha, yes! Over quinoa and tea. I hear you not only got to hug Carol Ann Duffy, but when she noticed one of your tattoos was a quote from Jeanette Winterson’s The Powerbook she took a photo of it and sent it to Winterson herself. So I take it you’ve gotten all you’ve ever wanted out of life now?

Aw man, I’m so lucky. I also got to have lovely conversation with her lovely partner, over dinner. Seriously, the hysterical, drooling scramble to buy the dinner tickets the minute they went on sale was totally worth it. Haha. I don’t know if I have gotten everything I want out of life, but if Winterson’s response to the tattoo is anything to go by, I can now at least confirm that I am living life well: “Thank you for the bodytext. Never to give way to indifference is the secret of life.”

You can buy Tender Delirium (Math Paper Press, 2013) online from BooksActually (which ships internationally), see more of De Rozario’s art, writing and curation work on her website, and keep updated on her work via her Facebook page.

Queer Singaporean women YESSSSS (the non-majority race-ness is a bonus) :D As a queer Malay Singaporean girl who loves theatre, what she says about censorship and the arts really resonated with me.

Also: ‘If you look at narrative work that has accessed mainstream appeal among Singaporeans (especially in film), the narratives that pull at the heartstrings of “common” experience revolve very much around “heartland” experience and our education system. And of course, the narratives are still overwhelmingly Chinese, heterosexual and male. It’s almost as if the idea of any alternative experience being seen as part-and-parcel of “national identity” (if there is such a thing) would be shocking for many people here. On one hand, that’s shitty. On the other, I’m quite glad that my life experiences are not being co-opted in an effort to construct some grand narrative.’

YES TO ALL OF THIS. I’ve also realised that even the queer narratives I’ve seen in Singapore theatre have all still been male, monosexual and almost completely Chinese (although of course I haven’t seen/read every queer Singaporean play so the situation might be better than what I’ve encountered).

Also this isn’t really relevant, but as a Singaporean studying overseas, I’m just happy to read something about Singapore :D

i had never thought about censorship of art in quite this way — this was really illuminating, thank you Fikri and Tania!

-melts into a puddle of fangirlyness.

Tania is so amazing. loved this interview, as well as the poem that was linked to. Making Trouble sounds like a GREAT project and I can’t wait to see what comes of it.