To begin Glitter Up the Dark: How Pop Music Broke the Binary, author Sasha Geffen offers a slight corrective: “The gender binary cannot really be broken because the gender binary has never been whole.”

Twelve chapters trace 20th century U.S. and European music history from the queer Black blueswomen of the 1920s like Ma Rainey through the internet-driven, gender-fucking pop phenomenons of the 2010s like Janelle Monàe and Perfume Genius. Geffen drags a shimmering thread that connects transgressive music histories that have defined not just queer culture but all of pop culture for decades.

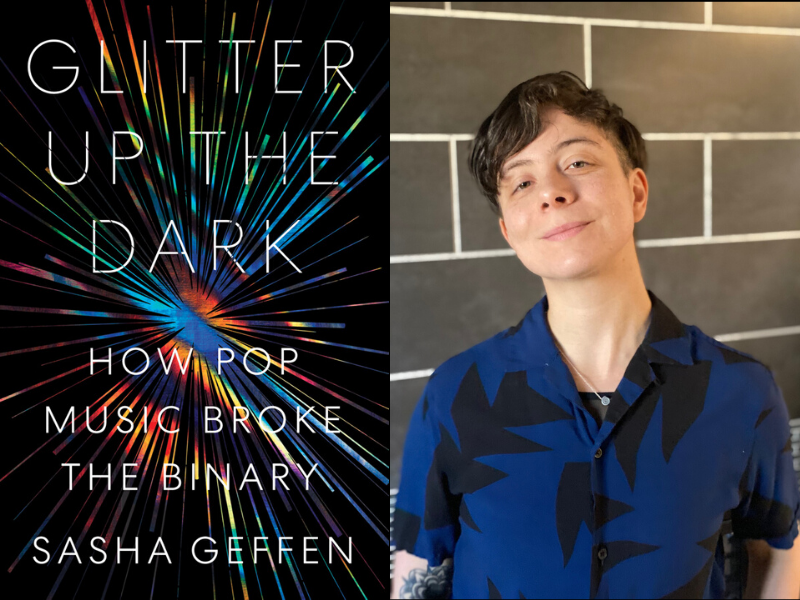

Glitter Up the Dark, which came out in April on University of Texas Press, is Geffen’s first book. They’ve made their mark as a music critic, with work appearing in Rolling Stone, Pitchfork, and elsewhere. The book is extensively researched but not overly academic, with accessible language and a driving passion that swept me away along with from beloved touchstones like Prince and punk into other genres, like industrial and disco, that I’ve never spent meaningful time with. The chapters are organized by genre and chronologically, and Geffen does most of the work for you to make it abundantly clear how these disparate characters, movements, and sounds relate to each other. They seamlessly mix history, music critique, and narrative essay styles to help connect artists, technological developments, and moments of impact to illustrate their thesis: the collision between gender, rebellion, and technology has made pop and rock music a vehicle for gender disruption for their entire existence.

Geffen’s book is not a history of trans musicians, though plenty of them are represented — for example, the wide-reaching influence of Wendy Carlos, who revolutionized electronic music, and Laura Jane Grace of Against Me! is clear in the text. Primarily, it’s an exploration of music as a mechanism for expressing and expanding complex ideas of gender that find their way into society as a whole and threaten patriarchal, capitalist norms. Throughout, Geffen pushes back against the whitewashing of narratives around genres like disco and electronic music to reveal the layers of queer Black influence on 20th century music. Queer Black artists had a much more significant and authoritative role in US music history across genres than mainstream music histories tend to acknowledge. Take the Beatles, whose “few extra inches of hair appeared [to mid-1960s America] not just as a social lapse but as a biological anomaly.” The overt influences of Black girl groups like the Marvelettes and queer male artists like Little Richard on the musical and vocal stylings of the Beatles made these non-normative expressions palatable to mainstream audiences, but they still carried some hint of the counter-cultural resonance onto the Ed Sullivan Show.

The book reveals the extent to which critics, fans, and time have flattened our readings of some artists. From the overtly queer origins of hip hop to the trans-inclusive beginnings of Riot Grrrl and Women’s Music, Geffen flips over moss-covered rocks to fill in oft-ignored details. The chapter “God is Gay: The Grunge Eruption” is a must-read for its analysis of how Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love flipped gendered scripts in their relationship and their respective bands, Nirvana and Hole. Though Cobain was known for wearing dresses and told Rolling Stone that he experienced attraction to people regardless of gender, he’s remembered as an ally rather than as a queer icon (note to self: make Kurt Cobain a queer icon).

Geffen deftly brings in first-person accounts and the writings of other critics and historians to fill in the details, then jumps in to convey why it matters. This pattern makes the book feel conversational and dynamic, especially when it digs into the stories of individual artists and moments. A rumination on Patti Smith mixes factual nuggets (Allen Ginsberg once tried to cruise her), highlights her inspirations (Jackie Curtis, Iggy Pop, Robert Mapplethorpe) and includes notes from her own diaries and writings where she reflects on gender and relationships (“I never wanted to be Wendy—I was more like Peter Pan. This was confusing stuff”) before tying it all together and pointing the way toward Smith’s indelible influence on punk.

Smith’s androgynous otherness manifested in her voice, which swung from deep, guttural grunts to piercing staccato shrieks…It’s a voice between genders, high enough in pitch to register as a woman’s voice but irreverent, arrogant, and blunt like a man’s. The burgeoning genre that would come to be known as punk dispersed this voice. (The word “punk” meant “bottom” at the time, lending the genre’s name an air of queer deviance from the start). Both Iggy and Patti echoed in acts that would typify punk, such as the Ramones, the Buzzcocks, and the Clash, whose singers found a grunt to work as well as a wail.

Tech is one of the book’s most salient themes, both in terms of music and gender. Technological innovations, from the creation of vinyl records to the popularization of the Moog synthesizer, the advent of music videos to the internet as a means of distribution, have each given musicians more ways to articulate and obfuscate gendered expressions. These developments created more possibilities for music and for trans people, and that has never felt more clear than in this book. Queer temporality, capitalism, the family, and racism and appropriation in the music industry all thread through the text. Of house music’s endless parties, Geffen writes, “In the now of the dance floor, gender and sexuality have no eventualities…the timekeeping of a normative life—birth, puberty, marriage, childbearing, death—falls away to the glow of the infinite moment.” Numerous such insights elevate Glitter Up The Dark from beautifully researched history to insightful cultural commentary.

If I had one complaint about this book, it would be that it’s so short! As each vignette rolled into the next, I found myself wanting more. Early 2000s emo, whose boys in eyeliner that made me extremely confused as a sad suburban teen, gets the slightest of mentions. Clocking in at an approachable 221 pages, Geffen’s book feels like the most fabulous tasting menu that will inspire readers to fall down the rabbit holes of so many of these stories. Fortunately, they made a playlist to go along with the journey.

Thank you so much for this review! Very excited to read this soon :)