feature image by Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

Over the last month, I’ve noticed a pretty disturbing trend in the way people are talking about what is happening in Palestine and the global response to the occupation. From what I’ve seen on social media, both liberals and conservatives who are in favor of Israel’s response to the events of October 7 have attempted to “call out” people in the U.S. over and over again for also being settlers on occupied land. Many of the criticisms of the ongoing resistance movement for Palestinian liberation here in the U.S. seem to hinge on this fact and appear to be making the claim that there hasn’t been a robust resistance movement against the U.S. government’s occupation of this land and its treatment of the Indigenous Nations of Turtle Island.

I’m not here to argue with them, because I don’t think we should be expending our energy arguing with genocide deniers under any circumstances, but the teacher in me is always instantly activated when people try to make claims about a past they don’t fully understand. It was yet another reminder about the lack of education many people have in regards to decolonial movements and actions here and abroad. I could point to a lot of different reasons why this happens, but it’s becoming clearer and clearer to me every day that people seem to have this idea that struggles against occupation and colonization are fixed in a very distant past that no longer has much bearing on the present. Not only is thinking of history’s impact on the present as minimal one of the most ignorant understandings of how the world works, but it also assumes there have not been more contemporary examples of resistance for us to learn from.

Unlike what some of these people might have us believe, there is a lengthy and robust history of resistance against occupation and colonialism led by Indigenous people here in the U.S. And I can’t think of a better time than Thanksgiving to reflect on it. The Thanksgiving story, like a lot of the narratives we learn about our history as Americans, is more often than not completely misconstrued, and that misconstruction is often wielded around as a weapon to try to convince us that the early colonists’ and the U.S. government’s treatment of Indigenous people here was “not that bad.” The many distorted narratives of the Thanksgiving story make the claim that the colonists were welcome with open arms and no questions asked, but the truth of the Thanksgiving story is actually much more complicated than that, as is every other narrative about this country we’ve ever been told.

Many Indigenous people have worked hard to try to correct this image that most Americans have of Thanksgiving and the relationships between their ancestors and the early colonists, and I’ve noticed throughout my career as an educator that more and more teachers have also answered the call to present a truer, more nuanced depiction of not only the Thanksgiving story but of the history of the genocide and displacement of Indigenous people in the U.S., as well. There’s no doubt in my mind that this has been an imperative step in the right direction for helping young people develop a better understanding of this country, themselves, and their place in it, but I can see that some people are missing an important aspect of the story of settler colonialism here. Although it’s absolutely necessary to discuss it, it’s not enough to depict the tragedies that were inflicted on Indigenous people and not show them as groups of people with their own agency and their own abilities to not only defend themselves from the colonist’s advancements on their land but also fight back against occupation.

Growing up in Florida in the 1990s, we learned early in our education about the great Seminole Wars of the 1800s. These were presented to us and taught to us as wars in the usual sense where two sides who have grievances against one another take up arms to solve those grievances, but the truth is much more complex than that. All three of the “wars” began as a result of Seminole resistance to the colonists’ and, eventually, the U.S. government’s attempt to occupy more and more Seminole land in various ways. First, as a response to the amount of unauthorized slave raids being conducted in Northern Florida Seminole territory. Second, as a response to President Andrew Jackson’s forceful insistence that the Seminoles leave Florida under the rules of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. And finally, as a response to the growth of colonial towns on the west coast of Florida. In the elementary, middle, and secondary school classrooms I was in as a kid, we were never given a full understanding of this story. Even if we felt it, there was no one to confirm our suspicions that the colonists and the resulting occupation of these lands were wrong, and there was certainly no one trying to make us understand that these weren’t just wars — they were struggles against that ongoing occupation.

The truth is that while many Nations were coerced into signing treaties or willfully did so and that while some Nations worked with the early colonists to ensure their own survival or just because they felt it was the most beneficial thing to do, Indigenous people in the U.S. never stopped resisting settler colonialism, white supremacy, and occupation. You can see they’ve done this in a variety of ways — through the preservation of the cultures and languages, through their art, through their fight for representation and visibility — but the stories of active resistance through direct action and violence in the 20th century, in particular, are much more obscured. But to fully understand the response to colonialism in the U.S. and to understand our potential for eventually dismantling this system, we have to become familiar with the people who have already done and are doing that work. We have to study up.

This is an examination and a celebration of the contemporary resistance history people want to claim doesn’t exist. Although the success rates of these movements vary, I think looking back on them can help us understand what we’re up against when we’re fighting against settler colonial and imperial powers and can help give us some ideas for new tactics and strategies we can utilize in the fight.

Occupation of Alcatraz Island, November 1969

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Although this particular action seems very well-known to me, it still feels as if it should be on this list. By the mid-1960s, the American Indian Movement (AIM) began to take more organized shape under the leadership of Clyde Bellecourt, Dennis Banks, and George Mitchell, and their organization began to inspire a new generation of Indigenous organizers willing to put themselves on the line to fight for Indigenous civil rights and restoration of land to Indigenous communities.

The occupation of Alcatraz Island that occurred in 1969 was actually preceded by a much shorter occupation of the island that happened in 1964. At that time, a group of Sioux activists had discovered Alcatraz was going to be vacated by the U.S. government, which according to the Treaty of Fort Laramie meant that the land should be returned to the original Nations who occupied the land prior to the U.S. government’s occupation of it. A group of Sioux activists staged a short takeover of Alcatraz in 1964 with the intention of turning the island into a cultural center for Indigenous people, but their plans quickly got more complicated as developers in the surrounding Bay Area got involved in appealing to the U.S. government for the land. As a result, a group of Indigenous organizers from all over the country came together under the group name Indians of All Tribes to plan and execute a larger takeover of Alcatraz in November 1969.

The takeover was led by Richard Oakes and LaNada Means but included over 89 other Indigenous organizers and activists who managed to set up camp on the island. Eventually, the takeover grew to include over 400 Indigenous people from different Nations all over the U.S. and, together, they created ways to sustain themselves and the community of people living there for the majority of the 19 months they were there. Pressure from the U.S. government, including the cutting off of fresh water, electricity, and telecommunications on the island prompted an end to the takeover, along with other interpersonal conflicts between the organizers, but the legacy was long-lasting and material in many ways.

Aside from inspiring an ongoing movement to reclaim Indigenous land, the Occupation of Alcatraz also inspired the writing and passing of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. The passage of this law forced the legal ending of the enforcement of a series of “Indian termination” policies passed between 1940 and 1970 that aimed to force assimilation on Indigenous people and helped give Nations more sovereignty over the financial decisions of what happens on land that belongs to Indigenous people. Of course, this did not change the fact of the U.S. government’s occupation or totally stop them from further persecuting Indigenous people, but it set legal precedent for land sovereignty disputes.

Puget Sound “Fish Wars,” September 1970

Yes, this is exactly what it sounds like. The Fish Wars were the result of a decades-long battle between the Indigenous Nations who populate the area around the Puget Sound, particularly the Nisqually and the Puyallup, and the state of Washington over the state’s laws against certain kinds of fishing in the waters of the Puget Sound. According to the Treaty of Medicine Creek that was signed by the tribes that lived in the Puget Sound and the U.S., the Indigenous Nations of that area were entitled to enact their traditional tribal fishing and hunting rights. But by the early 20th century, the state of Washington was doing everything it could to try to limit their ability to fish where and when they wanted to. The passing of various state laws as it pertains to what kind of fishing could be done in the Puget Sound, including the necessity for getting fishing licenses and permits, led to a series of arrests throughout the 1940s and 1950s of Indigenous men who were violating these laws.

Since the Nisqually and Puyallup viewed the passing of these laws as a violation of the Treaty, they first resisted by continuing to fish the waters as they always had. By the early 1960s, though, the response from state authorities continued to get more and more threatening and violent. In response, members of the Puyallup Nation decided to stage a series of “fish-ins” in part of the Sound called Frank’s Landing beginning in 1963. The “fish-ins” captured national attention for a while, even resulting in the arrest of Marlon Brando in 1964 for participating in one of the “fish-ins,” but they failed to help bring about a change in authoritative action by the state or materialize any legal precedent for some years. The “Fish Wars” really came to a tipping point in September 1970 when a group of Puyallup men decided to arm themselves in defense against state law enforcement. No one was killed in the struggle, but it did lead the U.S. government to finally step in and sue the state of Washington into making sure their laws were no longer in violation of the Treaty through what became known as the Boldt Decision of 1974.

Wounded Knee Occupation, February 1973

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

This event was precipitated by a number of very complicated reasons that relate not only to the U.S. government’s attempt to control what happens on sovereign reservation land but also to the differences in the way people on that reservation responded to the U.S.’s interference on the reservation. Despite the complexity of the situation, though, the Wounded Knee Occupation remains an important example of resistance against the colonial and occupying forces of the U.S. government.

Led by members of the American Indian Movement and members of the Oglala Sioux Nation, over 200 Indigenous people seized and occupied Wounded Knee, South Dakota in order to protest the U.S. government’s lack of adherence to the various treaties they’d signed with the tribes living around the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and tribes all around the country. The organizers of the occupation attempted to use the action as a way to force the U.S. government into reopening treaty negotiations and hopefully bring an end to the inequitable treatment of Indigenous people in the U.S. Led by Russell Means and Carter Camp, the occupation went on for 71 days as the state and local law enforcement, along with the FBI, did their best to intimidate and weaken the activists involved in the occupation. As the weeks went on, the U.S. government tightened their grip on the region — by trying to starve out the organizers, by intimidating them with violence, and by trying to prevent any aid from making it to the people who were occupying the town — and the conflict grew more violent as a result. Organizers working with AIM were killed and injured as a result, as were members of the state and local authorities and the FBI.

The aftermath of the Wounded Knee Occupation produced less material results but did lead to a recognition by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1980 that the U.S. government’s interference in tribal and reservation affairs was illegal according to the treaties they signed with the Sioux Nation.

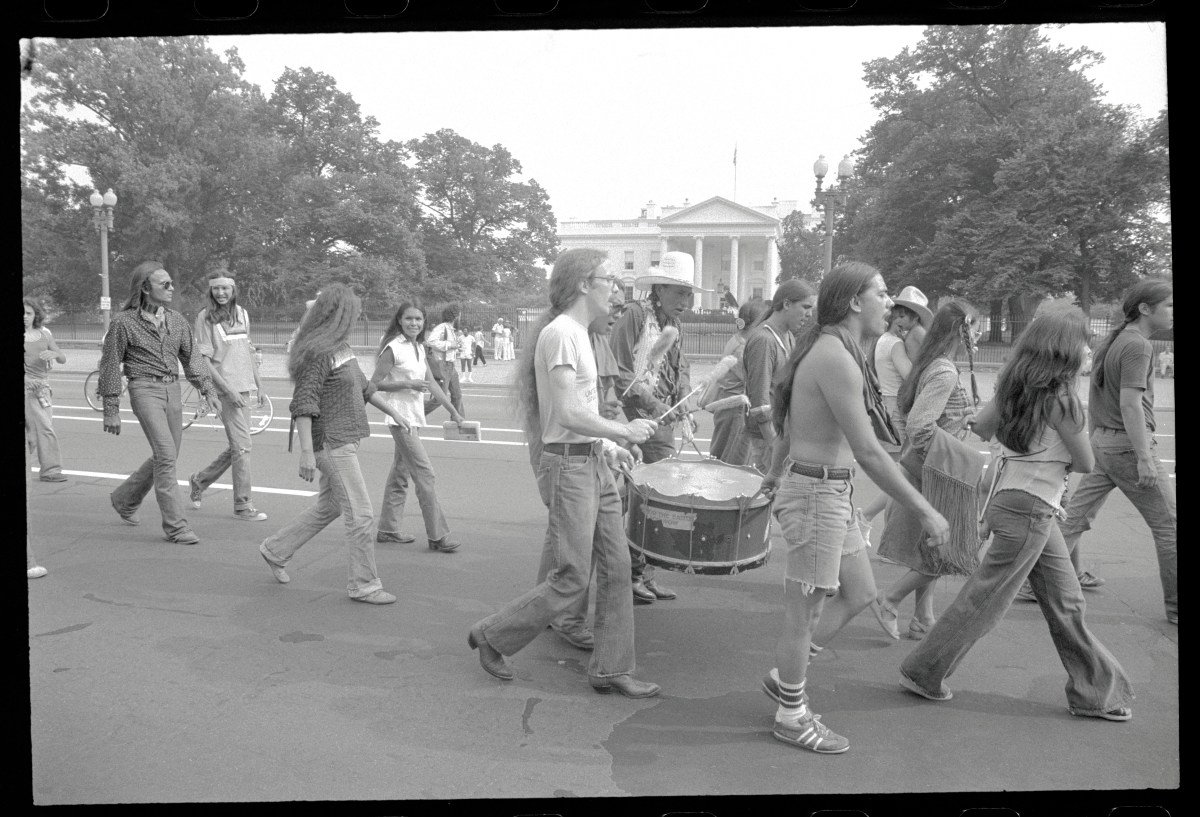

The Longest Walk, July 1978

Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images

By the end of the 1970s, the American Indian Movement had gained a lot of traction throughout many Indigenous Nations, and the U.S. government seemed hellbent on doing everything it could to worsen the treatment of Indigenous people as it possibly could. On top of the fact that Indigenous people were already struggling to find jobs, permanent housing, and healthcare due to discrimination and lack of opportunity, Congress was set to vote on a series of legislation that would effectively void many treaty obligations that the U.S. still had to Indigenous people. If these bills were to become laws, they would have drastically altered the lives of every Indigenous person and Nation in the U.S. by forcing them to cede sovereignty and reservation land rights to the U.S. government, among other things.

To help fight against this, Phillip Deer and a group of organizers from other Nations came together to plan a walk from Alcatraz Island to Washington, D.C., where they would then camp out on the grounds of the Washington Monument. Along the way, the 24 marchers who ended up walking the entirety of the 2,700 mile journey were joined by other Indigenous activists and their supporters as they made their way across the U.S. Once they arrived in Washington D.C., organizers and supporters camped out in Maryland for 12 days and led protests around the White House almost every day.

In the end, the action didn’t solve the issues that already existed. However, Congress voted “no” on each piece of legislation that threatened to take sovereignty away from Indigenous people.

Orme Dam Protests, November 1981

I wish there was more information available online about what exactly happened during the decade-long battle between the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation and the U.S. government, but there isn’t. I’m still including it on this list, because I do think it deserves a spot just based on the perseverance of the Yavapai people and their ability to keep fighting off the U.S. government and the state of Arizona for 10 whole years.

In 1968, Congress approved the Central Arizona Project, which was a development project designed to essentially make the land more hospitable for (white) American people to move to Phoenix and other parts of Central Arizona. Part of the plan was to build the Orme Dam in order to build a small reservoir off the Salt and Verde rivers. The Secretary of the Interior claimed the reservoir was for the Indigenous Nations around the area, but the truth is that the construction of the dam would flood more than half of the Yavapai reservation and would diminish the tribe’s ability to keep farming on their land. In response, the Yavapai Nation staged a series of protests over the course of 10 years to fight to keep the dam from being built.

They were finally able to stop organizing when the U.S. government decided to cancel the building of the dam in November 1981. Today, they celebrate this huge win for land rights at the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation Orme Dam Victory Days Pow Wow in early November every year. So, not only did they win, but they also haven’t let anyone forget it.

Keystone XL Pipeline Protests, August 2011 – June 2021

Photo by NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP via Getty Images

When I thought about including this on the list, I was a little hesitant at first. The organization in opposition of the Keystone XL Pipeline was a group of environmentalists that included and was led by Indigenous people of South Dakota and Montana, but wasn’t exactly initiated by them. Regardless, though, the actions against the Keystone XL Pipeline were still largely planned and fronted by members of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe of South Dakota and the Fort Belknap Indian Community of Montana, among many others.

The Keystone XL Pipeline was a proposed pipeline that would transport crude oil from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada through Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, eventually ending in south Texas. From the very beginning, climate activists and organizers were opposed to the construction of the pipeline, but the pipeline’s proposed pathway through many tribal lands and waterways eventually brought more people to fight against it. Starting in August 2011, there were a series of actions held at the White House that resulted in over 1,000 arrests and more significant growth for the movement against the pipeline. In November 2011, thousands of protesters managed to form a human chain around the White House in order to get then President Barack Obama to halt construction on the pipeline. From there, the movement expanded to other areas of the country as protests were held throughout the years in Montana, South Dakota, Oklahoma, and Texas. In 2015, Obama canceled proposed construction of the pipeline only to have the construction proposal renewed by President Trump when he took office.

The culmination of this decade-long battle came when members of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe of South Dakota and the Fort Belknap Indian Community of Montana held their own public hearings about the Keystone XL Pipeline and then eventually filed suit against the Trump Administration for their continued support of the construction of the pipeline. Because of the lengthy fight against the pipeline and the continued battles in court, the developer of the Keystone XL Pipeline decided not to move forward with the construction and abandoned their plan altogether in 2021.

Dakota Access Pipeline Protests/Standing Rock Protests, April 2016 – February 2017

Photo by Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

Maybe you’re unconvinced how the fight against the construction of a couple of pipelines could really count as a decolonial struggle, but the fact is that both the Keystone XL Pipeline and the Dakota Access Pipeline are just the newest installments in the attempted expansion of the colonial powers of the U.S. And the struggles against them overlapping just serves to illustrate this further.

Similar to the Keystone XL Pipeline, the Dakota Access Pipeline was built to transport crude oil from North Dakota to Illinois, only the distance was much shorter and cut through not only tribal lands but specifically sacred tribal lands and also threatened to pollute the water of Lake Oahe, a large reservoir that serves both the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation and the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. In response to the proposed construction of the pipeline, a group of young Indigenous activists from Standing Rock and other reservations in the area came together in the spring of 2016 and then created a Water Protectors’ camp that interfered with the path of the proposed pipeline. The protest first began as a simple occupation of space until state, local, and Federal authorities continued to exert pressure on the Water Protectors and their allies to abandon the occupation and get out of the way. By September, organizers and activists who stuck with the occupation began to experience several threatening attempts by private security forces hired by the developer of the pipeline and the local authorities. Violence escalated as the private security forces attempted to evict the protesters. Even though many people were hurt in the struggle, the escalation of the violence drew more attention from the media, politicians, celebrities, and other Americans who could see the attacks play out in the media and on social media.

For the next few months, the organizers and activists who stayed at the camp would experience more violent attacks from the authorities and private security forces. As the harshest parts of winter set in on the camp made the situation even worse for the activists who were still there, many decided to leave the camp in January 2017 but it still took a forceful removal of the final activists left in February 2017 by the U.S. National Guard for the occupation to end officially.

While the Standing Rock protests were not successful in getting the Dakota Access Pipeline shut down, it still serves as one of the most important actions led by Indigenous people against the U.S. government in recent years. Since 2017, pipeline protests and protests against illegal development of Indigenous pop up all across the country utilizing some of the strategies used in the Standing Rock protests.

While the majority of these were huge actions that had long-lasting impacts on both the lives of Indigenous people in the U.S. and the way the U.S. government interacts with them, it’s important to remember that these are just a few of the resistance actions taken up by Indigenous people in the U.S. in recent years. As the national and international conversations on colonialism, imperialism, and decolonization progress and spread, I think it’s important for us to continue reflecting on the big and small ways Indigenous groups in the U.S. and abroad have challenged and fought against the occupying, colonialist, imperialist forces that have attempted to wipe those groups off the map entirely. And it’s important for us to stand with them, as well. The fight for the liberation of all oppressed people is not going to stop being violent, difficult, and dangerous. At the very least, we owe it to our predecessors to take the lessons they’ve behind seriously.

Such a good and necessary post.

Such great information on indigenous activism, and I almost didn’t read it because of the first paragraph. :(

Indigenous activism and resistance don’t tend to be popular at the time they happen. Resistance is often only recognized as justified years later. But we don’t resist colonialism and strive for decolonization because it’s popular. And we don’t prented that colonizers will peacefully give us back our land when they took it by force and maintain control with violence and oppression. We rightfully question the “Thanksgiving” narrative that whitewashes the history of colonialism in North America.

Israel is a decolonial success story, a victory for the indigenous people of the land who dreamed and planned and fought and prayed for a future where they could live and prosper in their indigenous homeland. One day, that will be wildly accepted as true, but right now distortions of history (and outright jewhatred) are muddying the waters for people who are sadly unaware of the history of the land.

It’s disappointing to see you talk about respecting indigenous people and movements on one hand, and then see you also try to delegitimze a specific indigenous group because you don’t approve of how they are defending themselves after a genocidal attack at the hands of one of their former colonizers. Criticism is ok when it doesn’t include stripping indigenous people of their indigenity and connection with the land. But denying people their indigenous identity because you disagree with their government or their leaders is not the way. We don’t have to earn our indigenity with behavior that outsiders see as “good” or “correct.”

Every decolonial movement is unpopular at the time it’s happening. I’m an indigenous person who longs for decolonization, and I stand with the indigenous people of Israel who have achieved that dream.

There is a lot of history in that region of the world. However, I have yet to discover where Palestinians past or present colonized Israel. Kindly point to materials that explain the details.

As far as “jewhatred,” I find it quite interesting how some of the staunchest non Jewish Israel supporters are actually anti-Semitic. Them saying I support Israel is a nice way of saying go back to Israel. They don’t care for Jews or Muslims and privately hope the two groups kill each other.

If Hitler were alive today, he might feel the Holocaust was justified as a struggle for Indigenous rights. He somehow felt he was the victim of a marginalized group.

Regardless of who was Indigenous or in power, attempting to permanently eliminate an entire ethnicity is wrong. I don’t want to be complicit in Netanyahu’s Final Solution.

This is an amazing article. I learned so much and itching to learn more. Thank you for writing it

Thank you for writing this article and giving us a starting point to learn more. Sadly I only kind of heard of Alcatraz, etc and others not at all. Thankfully I heard more on the pipelines.

I hope and pray Leonard Peltier will be free.