Black History Month is often focused on prolific members of the Black community throughout history who contributed to the world in the name of betterment, and while they are incredibly important to our community, we often overlook those who are still alive and continuing to make a difference. We know that much of the fight for LGBTQ+ liberation has largely been led by Black members of the community who often don’t get enough credit for their contributions. This year, the Autostraddle team decided to focus our Black History Month coverage on the Black elders who are still here and still doing the work.

We connected with Black elders through a partnership with SAGE, the world’s largest and oldest organization dedicated to improving the lives of LGBTQ+ older people. Founded in 1978 and headquartered in New York City, SAGE is a national organization that offers supportive services and consumer resources to LGBTQ+ older people and their caregivers. Autostraddle was honored to talk with five Black LGBTQ+ elders, and we’ll be publishing these interviews throughout the month of February. We welcome our readers to celebrate these members of the Black LGBTQ+ community with us, while they’re still here to be celebrated.

I can count the times I’ve been to Atlanta on one hand — once on a family vacation and another time, almost twenty years later, for work. Both times, I found myself wondering what it would be like to exist in a space so rich with Blackness, charm, and melanated queer community — what possibilities exist in a richness that defiantly merges past, present, and future? Last month, I got some answers and the results are shared in the beautiful transcript below.

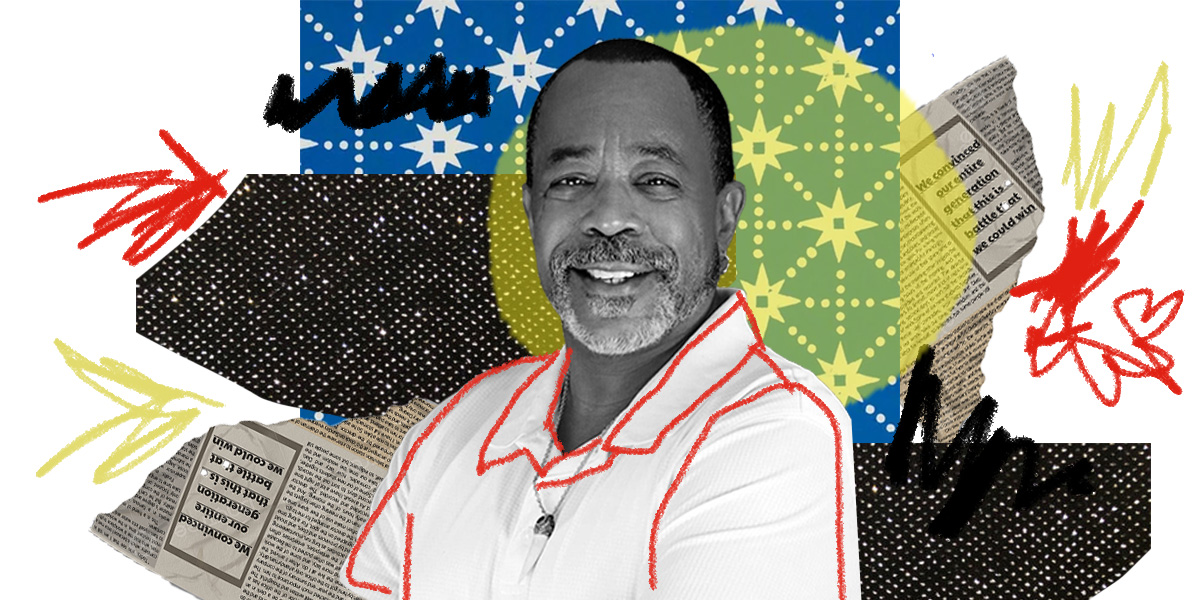

I spent an hour in conversation with Black Atlanta’s gay uncle, Malcolm Reid — a passionate advocate and community organizer who’s spending “retirement” creating affirming spaces and programs for HIV-positive elders. Despite calling Atlanta home for the past four decades, I immediately hear New York in Malcolm’s voice when he talks of the wonderful relationship he had with his mother and his upbringing. “Atlanta is home,” he asserts though. In our conversation, we cover a lot — growing up Black, boy, and not-yet-gay in New York City, coming out, falling in love with Atlanta and his husband of 26 years, aging with HIV, and the importance of community for Black LGBTQ+ elders all over.

At 65, Malcolm Reid’s journey of finding self, home, and fighting like hell is one that reminds us that there is nothing more beautiful than building the life we deserve with the ones we love.

shea: Let’s start at the beginning – where are you from? What was growing up like?

Malcolm: So, I’m 65 years old. I was born in 1957 at St John’s Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. For the first four and a half years of my life, I lived in Brooklyn. And then my mother and father separated. So we moved to the Bronx and moved into Castle Hill Projects. In Brooklyn, we were living in Brevoort projects. Then we moved to the Bronx to Castle Hill Projects. I will say that back then the projects were the “lower middle class,” and “mid-middle class” housing for people. My mom always said that people that lived in the projects back in those days all had good jobs. They all wore uniforms to work. They were either nurses, cops, people that worked for the city or the post office, or whoever.

My mom was a nurse and it was just her. Growing up, we struggled but my mom always made sure that whatever she had to do, we (my sister and myself) were going to go to Catholic school and we were going to get the best education we possibly could. So with the help of her mother, they made sure that we had the best upbringing as kids as we possibly could. Then later on, she met a man and had my two other little sisters. So then we were a family of four with a single mom living in the projects. And I mean, we knew that we didn’t have everything, but we didn’t know that we were poor. You know what I mean?

My sister and I attended a Catholic high school, but my two younger sisters were the first kids in the family to go to the public school system. Mom was really cognizant of the fact that I was the only boy in the house and she didn’t want me in public schools. Even back then, she didn’t want me in public schools. So she made sure that we both graduated from Catholic high schools.

That was my upbringing. I was very much a typical boy – playing basketball and football, going to the community center, and all that New York stuff. I was hanging out in the street and doing all of that, getting in trouble, and all of that good stuff.

shea: You mentioned your grandparents helping take care of you. Can you talk a little bit more about the relationship with your grandparents and the intergenerational care network that helped raise you?

Malcolm: Oh yeah, I’d be happy to. Actually, I just want to take a minute to tell my grandfather’s story because it is the story of Black America. My grandfather was a twin, his name was Herman, and his brother’s name was Thurman. I never met Thurman — Thurman died. I can’t remember how old he was when he died, but he died long before I was born. But one day, my grandfather and his brother left Wilson, North Carolina, and they walked to Richmond, Virginia, got on a freight train, and ended up in New York City.

I always tell people, had the train ended up in Chicago, that’s where we would’ve been born. If the train ended up in Los Angeles, that’s where we would’ve been from because when they got on the train, they didn’t know where it was going. They just knew that they had to get out of the south. So, he got to New York and met my grandmother, and my grandfather and grandmother were together for 67 years before my grandfather passed.

When my mother and father broke up, my grandparents knew my mom was going to need help and they made sure that she was able to move from Brooklyn to the Bronx so that we could all be close together. They lived in the projects as well. Even though he wasn’t in the house with us, my grandfather was pretty much the man in my life. My father was around. He would come around and give my mother his little $30 a week or a month or whatever it was, but my grandfather was the person who taught me how to drive. My grandfather was the person who just made sure that I knew that it was about being a man — taking care of your family, taking care of your sisters, and doing all of that, because like I said, I was the only boy.

Now, I will interject and say that when I was eight years old, my father came by to give my mother some money. I think I was acting up, and my mother was always like, “I’m going to tell your father when he comes.” So she went and told him I’d been acting up and he came over and he did what parents did back in those days — he spanked my butt and then told me that I was the man of the house now. I was eight and I was the man of the house.

At my mom’s funeral, my sister reminded me of what happened next. She said, “yeah, and a couple of weeks later when you were walking around puffing your chest out, talking about you were the man of the house, mom grabbed you and pulled you to the side and said, ‘You are not my husband!’ Because I was bossing my sisters around and telling them what they should be doing. I was a bit of a terror back then!

My grandparents lived in the building directly across the street from my grade school. Their windows faced the school and my grandmother was always in the window watching what was going on. In New York, back in those days, the schools had a schoolyard, but they would also close the street so that the kids could play out in the street. If we were out in the street or in the schoolyard, my grandmother could always see. And whenever there was anything going on, she was on the phone calling my mother, “Malivene, you need to come up here after you get off of work!”

So yeah, it did take a village. Our friends’ parents and grandparents were always in the window looking out and seeing what was going on in the street. That’s how I grew up.

shea: That idea of a village just seems so different from mainstream culture today. A lot of kids aren’t outside, you don’t really talk to your neighbor. It’s so different from even the times when I grew up. Back then, it seemed like we knew everyone on the block and just living community.

Malcolm: And not only that but, Ms. Jones could come up to my mother and say, “Hey, I saw Malcolm on the basketball court doing so and so,” and my mother wouldn’t even ask any questions. She’d come home and spank my ass, because Ms. Jones had no reason to lie on me, right? Imagine telling parents today, “hey, I saw your child doing this or that.” They’d just look at you and say, “mind your own business.”

shea: Yeah. I remember growing up that if I was at my grandmother’s house or at church and one of the other old ladies saw me being mischievous, they would spank and then before I could get home, they would call and my grandma would get on me too!

Malcolm: Exactly.

shea: It was a community effort, definitely. But yeah, times are definitely changing.

Malcolm: Indeed.

shea: I want to just talk more about your relationship with your father and your grandfather, especially being a gay Black man. Could you talk a little bit more about that? Were you out to them? What were your relationships like?

Malcolm: No, I did not come out until I was 28 years old. I moved from New York to Atlanta when I was 23. And I moved to Atlanta so that I could be gay. There was such a stigma back then. My father’s favorite word was faggot. As I was becoming a teenager, he tried to be a part of my life, but he really wanted to be my buddy. He wanted to hang out. He wanted to teach me how to do all the “manly” things — how to go out to the club, how to drink, how to smoke cigarettes, how to do all of that stuff. Just feeling that stigma of growing up in the projects and the barbershop and just on the basketball court, playing basketball in school, and laughing at sissies and all of that stuff — I knew that I could not be gay in New York, so I hid it.

I started driving a cab in New York when I was 18 and those were my first sexual encounters. I would meet guys down in the Village and have little anonymous sexual hookups, but I was still very, very scared and very, very intimidated.

When I moved to Atlanta, I started to explore. My first ever relationship was here in Atlanta. After I got comfortable with him, I said, “Okay, it’s about time that I tell my folks.”

shea: And you were 28 then?

Malcolm: Yes and by that time, my older sister had moved down here as well. For me, that was kind of stressful too, because like I said, I moved to Atlanta to be gay, and now here she comes, right? I’m like, “why you got to come down here?” But she came down, and so she told me she was going to go to take the train back to New York to visit. So I wrote a letter to my mother telling her that I was gay. I also put in the letter that if she decided that she wanted to disown me, I would understand.

I wrote that in there because over those five years, between the age of 23 and 28, becoming involved in the gay community here, I knew plenty of people, especially from the south, whose parents had disowned them. Some of my best friends were people that didn’t have any place to go. They lived in shelters or whatever. So I made sure that I said that. The letter was cathartic for me because I knew that once I wrote that letter, I was free. Once I handed it to my sister, I was free. I told her, I said, “I’m going to give you this letter. Do not read it. Give it to mom when you get there.”

That was the first night that I went to a gay club in Atlanta. I went to a club called Foster’s, which then became Loretta’s. I had a great time that night. I mean, I just partied and I got home at God knows what time in the morning. Then, I spent the next day just pacing the room, waiting for the phone call.

About three o’clock in the afternoon, my mom calls me and she’s being quintessential New York mom, she’s talking about everything else but [the letter]. She’s like, “Your father’s had a flat tire. Your father decided to come to help me pick up your sister. I don’t know why he decided to be bothered, but he did. And of course, your father and his old raggedy cars, he had a flat tire,” and da, da, da. And I’m sitting on the phone thinking, Jesus Christ.

So finally she says, “So your sister gave me your letter and I read it. I have a question.”

I said, “What’s that, ma?”

She said, “Don’t you know your mother loves you?”

And I said, “Yeah, mom, I know.”

And she said, “So what’s this nonsense about me disowning you?”

I said, “Well, mom, I had to put that in the letter because I know so many people who that has happened to.”

She said, “Well, I’m not them. So don’t even!” Basically, so don’t go there with me. And then the next question she asked was, “Do you have somebody special in your life?”

And I said, “Yeah, I do right now.” She said, “Well, that’s good.”

Then we went on with the rest of the family conversation. Eventually, she asked, “Do you want me to tell your father?” I said, “I really don’t care. If you want to tell him, fine, you can.” She said, “What about your sisters?” I said, “Well, Kim and Nicole,” who were still living in New York at the time, I said, “Yeah, you can tell them.” I said, “I’ll tell Karen [the sister who moved down to Atlanta] when she gets back here.” So she said, “Okay.” That was our agreement, and that’s where we left it.

Over the years, my mom was a godsend to me because she was a nurse. In 1997, when I found out I was living with HIV, I was able to talk to her about things. A lot of my friends didn’t have that resource. She was able to tell me a lot of information. My mom is one of the reasons why I never got on AZT. My mom was like, “No, that’s killing people. Don’t do that.” She said, “They talk about it’s prolonging life, but it’s not giving anybody quality of life.” She said, “So don’t do that.”

And as my mother got up in age, I was able to move both her and her husband down here to Atlanta in 2012 and she lived down here until she died in 2020.

shea: Wow what a journey. So it sounds kind of like Atlanta is kind of home for y’all — or do you still consider New York home?

Malcolm: Oh no. I mean, sports — I’m still a Yankee fan, a Knicks fan, and a Giants fan. I will carry that with me always, so I’m a New Yorker at heart, but Atlanta is home. My whole family’s here now. All my sisters are down here. I’ve got friends and a solid community here. Atlanta is home.

shea: How did you choose Atlanta? I feel like a lot of people view New York City or San Francisco or LA as the places you want to go when you’re coming out. If you’re not in one of those places, you want to get there. So what drew you to Atlanta? How did you get there?

Malcolm: Like I said, I was driving a cab and my cousin — well, he’s not really my cousin – we grew up together as cousins. One day, he wrote me a letter. He was at Clark. It was Clark College back then before it became Clark Atlanta University. He was telling me how wonderful Atlanta was and how Black Atlanta was. Not knowing that I was gay, he was, “Man, do they got some fine honeys down here, man. You need to come down here.”

He eventually invited me to come down in September of 1980. I came down for a couple of days. I was supposed to come down for like a weekend and hang out. I ended up staying for three weeks, and really, really fell in love with the city. I still didn’t explore my gay side, but still was enamored with the Blackness that was here. It was like, not only were there Black people here, but Black people were here doing well. I also was drawn to the history. I’ve always been a political junkie. Growing up in the 60s and 70s, it was always about the Black Panthers, the Civil Rights Movement, and all of that stuff. So just seeing where Martin Luther King, Jr. had been and where all of this history happened was just amazing to me.

So when I went back to New York, I decided to drive my cab until the wheels fell off, make as much money as I could, and move back down to Atlanta. And that’s what I did. I moved down to Atlanta on December 18th, 1980. Before moving there, I did have this long list of cities that I was going to live in. I was going to explore the country. I was going to move to San Diego and I was going to live in San Francisco. I was going to go to all of these places. I parked my butt in Atlanta and never moved.

shea: I mean, Atlanta’s a great place to be though.

Malcolm: Oh yeah. Looking back on my life, I was definitely supposed to be here.

shea: That’s beautiful. Can you tell me more about your life in Atlanta and how it’s changed over the past few decades?

Malcolm: As I mentioned, I started dating a man when I was 28. I started to feel secure. The only thing about that relationship was that he was a little closeted too. He had his friends, but they didn’t go out much. They had house parties and everything else, but they kind of stayed to themselves. I wanted to explore more, so I moved on and met somebody else that had more friends, was doing more things, and was more out in the community. And so over the years, I’ve just continued to be a part of this community. Right now, if I walk into a bar with someone, they’ll say, “Dang — do you know everybody?” and I go, “Yeah, I’ve kind of been here for a long time.”

But the best thing about Atlanta is what happened in ’97 — I met the man who is now my husband. We’ve been together for 25 years. Now we’re both 65 and elder and we just have a lot of friends who feel like family.

shea: Ohhhhh! Tell me about your husband and all of the lovey-dovey things! Where did you meet?!

Malcolm: We met in the club, girl. You don’t meet a good man in the club! Well, I did. I had always been in long-term relationships. I was dating a guy for a while who was super jealous all of the time. I broke up with him, met this other guy, and he just was abusive — not in a physical way but abusive like he was trying to find himself, and quite frankly (excuse my French, there’s no other way to say this) he was fucking everybody in Atlanta. But, I was in love and so devastated.

So my friends told me, “You need to stop these long relationships. You just need to date, go out, and have dinner with guys.” So I did that. I dated a couple of people. I met one guy. He was really, really nice. We dated for a while but then it got time for us to have sex and it was horrible. So I got mad at all my friends. I was like, “Don’t ever give me advice again. I’m sick of y’all.”

After that, I called one of my friends on a Thanksgiving night and said, “I’m going to the club tonight. I’m going to have me a cocktail, and I’m going to be cute, and I’m going back to my old ways.” And he was like, “Okay if that’s what you want to do, let’s go.” So we went to Loretta’s to dance and I saw the guy that I had been dating. So I went upstairs to the bar and I was sitting at the bar all by myself — this big ole bar. They had just constructed this new bar at Loretta’s and it was huge. I looked across the bar and the bartender was on the other side of the bar talking to this group of people. When I looked at the group of people he was talking to, I saw this guy and was like, “Damn, he is gorgeous.” And he started looking at me!

The guy started walking around the bar toward me. Our eyes were on each other the entire time. He walked and walked and walked, and then was going to try to walk by me! And I was like, “Wait, wait, wait, wait — no, HELL NO!” So he’s like, “What?” And I was like, “You’ve been looking at me from way over there, I’ve been looking at you, and you just going to walk by and not say anything?” So he came over and we started talking. He bought me a drink and we started drinking. The next thing I knew, I was going down to the dance floor and I told my friend, Reggie, “Come get your coat out of my car because I’m leaving.” He was like, “You leaving? Where are you going?”

I said, “I met this dude.”

Reggie said, “You just went upstairs.”

I said, “Yeah, and I am leaving.”

We went to his place and we have been together ever since.

After we moved in together, we had a little barbecue at my house and he invited his whole family over. That night he said, “Baby, my family loves you.” I said, “That’s good. I’m glad.” He said, “No, you don’t understand. They ain’t never really seen me date anybody,” because he hadn’t really brought anybody around his family.

He said, “My nephew and my niece grabbed me and pulled me in the corner and they said, ‘Yo, Unc, don’t fuck this up. We like him.” And our families are still tight.

Working in the field I do, talking to gay men all the time, listening to the troubles that they have dating and relationships, and everything else — I realize that I’m blessed, but what I won’t do is give relationship advice. I tell people all the time, “Y’all’s problem is you keep trying to model your relationships after somebody else’s models, but you have to figure out your own path. What works for us may not work for you.” But ours does work.

shea: Amen! So do y’all have any kids of your own?

Malcolm: No, no. We have nieces and nephews. And then we literally have the Atlanta Black gay male community as nephews. I mean, if I walk into the bar, I hear “Hey, Unc!” all of the time. That’s who I am. As a matter of fact, my real nephew called me one day and said, “Uncle Kevin . . . Me and Ian are your only nephews, right?”

“Yeah!” I said.

“So how come everybody on Facebook calls you Unc?” he asked.

I said, “That’s just a term I’ve been deemed in the community.” I had to explain it to him.

shea: Yes for community! Tell me more about your work in the community and your journey living with HIV advocacy.

Malcolm: I work at an organization called THRIVE SS. And THRIVE stands for Transforming HIV Resentments into Victories Everlasting (the SS stands for Support Services). I retired from AT&T at the end of 2019. Prior to that, in 2017, I had started a program for Black gay men my age (over the age of 50) living with HIV, called the Silver Lining Project and that was under the THRIVE umbrella. So when I left AT&T, I became the program manager for the Silver Lining Project. Then in 2019, I became the Director of Programs for all of THRIVE and that’s the role I hold today. I just love being able to serve the community. I don’t get out in the street and do much outreach anymore. We’ve got more staff for that now, but I like putting together programs, making sure that the programs are working, and making sure the staff has what they need. I also do a lot of political advocacy. I’m the Federal Policy Chair for the US PLHIV Caucus. I also serve on a couple of community advisory boards and other coalitions. I try to keep my hand in policy work too because I think that that’s important.

I can’t complain. Life has been good. As a person diagnosed with HIV in the late nineties, I’m fortunate that I was diagnosed after ARTs. But let’s go back to my mom telling me about AZT. So in 1991, I read a story in Ebony Magazine about a Black man who had the “new gay plague” or whatever they were calling it at the time. I think they might have called it AIDS, but there was also HTLV-III and some other terms being used. One of the things that they said about him was that the lymph nodes on his neck were swollen. When I read that, it kind of scared me because the lymph nodes on my neck were swollen at that time. So I remember going to the phone and calling my mother. There’s a famous corner in Atlanta. There was a Krispy Kreme donut shop on the corner of Ponce de Leon and Argonne. Everybody knows that Krispy Kreme shop. It was a block away from my apartment and it had a payphone nearby. I walked to that payphone, called my mother, and told her about the article. I just started crying and said, “My lymph nodes are swollen.” She told me to calm down and said, “First of all, your lymph nodes could be swollen for a whole lot of other reasons, so let’s not jump to any conclusions. I want you to go to the doctor and they probably want to biopsy it. Let them biopsy it, let them tell you what it is.”

So I went to the doctor. The report came back a few weeks later — mostly medical jargon, but basically it was consistent with HTLV-III.

When I told my mom, she asked how I felt and I said, “Fine.” That’s when she said, “They’re going to want to put you on AZT — don’t let them do that. Just make sure you take your vitamins and make sure you eat well. It’s going to be okay. They’ll find something else.” So that’s what I did and I didn’t really think about it anymore after that. I mean I knew I had this thing, but I was feeling good and I just made sure that I kept up with my health. That was important to me.

shea: Talk to me a bit more about your policy work and organizing.

Malcolm: I’m the chair of the Policy and Action Committee for the US People Living with HIV Caucus, I am on the HIV Aging Policy and Action Coalition, and I’m on several community advisory boards for the metro Atlanta area. And you know about AIDSWatch, right?

shea: Yes, but tell me more!

Malcolm: Okay. So AIDSWatch happens every year. This year it’ll be in March. The last three years really were virtual, but this year we will be in person again — I’m looking forward to that. During AIDSWatch, we go to DC. The purpose of the convening is to make sure that we are building a community of advocates and that people know what the issues are, and what we’re advocating for — funding for the Minority AIDS Initiative, funding for the Ending the Epidemic Plan, and more, like funding to help reduce stigma, to stop policies that stigmatize gay and queer people, like in Florida for example.

I like being out at the forefront of the work and also behind the scenes, just trying to make our voices heard, my voice heard. I started the Silver Lining Project when I was working for AT&T and living with HIV. At AT&T, I had great insurance. My husband was a makeup artist with Estée Lauder, he had great insurance. We were fine. We were doing it, clubbing on the weekends, having a good time, and not thinking about anything. Then I started talking to people and they would talk about how they have to re-certify for ADAP every six months. And I was like, “What do you mean you got to re-certify for ADAP every six months? Your HIV is not going away every six months? What is happening here?” And they were like, “No, you got to re-certify to ensure your income hasn’t changed.”

I realized how that process was holding people back from life. People didn’t want to get promoted because if they got promoted, they would make more money and then lose their benefits. Other people were living on disability and then they wouldn’t come off of disability even though the medication was working and they were no longer “disabled,” because if you started working then you might reach the income level where you could “afford” your medication [without benefits]. I was like, “That’s crazy.” So I said, “Okay, let me see what I can do.”

I tell people this all the time, when you put something on your heart and the universe sees that it’s all good, the universe will send you the people or the tools that you need to make it happen.

A little bit later, I went on a Same Gender Loving Cruise and I met two friends of mine, Craig Washington and Jerome Hughes. Craig was already involved in the community and he was asked to hold a talkback at the end of the cruise about our experiences. The next thing I know, I found myself up on stage disclosing my status. When I did that, Jerome came to me and said, “Hey, I have this group that you might be interested in.” I said, “Okay, invite me.” The way he came up to me though, I was like, “Dude, is this Amway? Because you sound like Amway.” [chuckles]

So in October 2015, I went to the group — it was just all these guys in Atlanta living with HIV — some of them who I had seen on a regular basis. Half the room, I knew, because we’ve all been out in the clubs and everything else. I was like, “Holy crap. All these guys are living with HIV.” That group eventually blossomed into THRIVE. They were incorporated in December 2015. The group was founded by three Black gay men living with HIV — Daniel Driffin, Larry Walker, and Dwain Bridges. It was designed for us and by us. It’s been going strong for seven years. We are a membership-based nonprofit and we have probably the largest member organization of Black gay men living with HIV in the country.

Eventually, I started looking around, but I didn’t see anything for people my age. I would go to meetings and everything else, but everything was about young people. I was like, “This is kind of messed up and I don’t see anything for my age.” And then somebody said, “Well, there is an organization for older LGBTQ people called SAGE.” And I was like, “Oh, okay, let me go check them out.” But SAGE down here ain’t SAGE in New York [chuckles]. SAGE down here was very, very white and very, very old. It wasn’t working for me.

One day, I’m at a meeting and Larry, the THRIVE Executive Director said, “Well what have you experienced?” I responded, “Listen, I don’t see anything out there for guys my age.” He looked at me and said, “Well start it.” I looked over my shoulder, looked at him, and I was like, “Who me? Start what? I don’t know nothing about this. I work in corporate America. I don’t know nothing about no nonprofit stuff. I don’t know anything about this.”

But again, God sends you the people, the universe sends you the people. I met two guys — Claude Bowen and Nathan Townsend. The three of us sat down and we wrote a grant for the Silver Lining Project to get it funded. And it got funded, and it got funded massively. It was like a $400,000 grant for three years!

shea: Whoa!

Malcolm: And so with that money, THRIVE was able to get a building that we’re still in today and then start to gather other funds. We put together a program called Silver Skills, where we teach the members of the group about HIV and aging. What is HIV doing to your body? You may be on your retrovirals, you may feel better, but what is medical science saying about this? Why are you feeling the way you do? PTSD and trauma, dealing with growing up Black, growing up gay, growing up living with HIV, what are all those traumas? What things are you going through? Loss and depression? Many of us have lost friends and connections. Finally, the program ends with talking about stigma — what it’s about and how to overcome it.

We did that curriculum for three years. We met on a weekly basis or every two weeks with what we call Oba’s Roundtables, “oba” being the West African term meaning king or leader. We did Oba’s Roundtables on a regular basis, and then just had events and parties. One of the things that we pride ourselves at THRIVE and Silver Lining about is when you walk into this building, we don’t want you to be holding your head down and going, “Uh-no, I got HIV.” It’s about self-love. We want to have a good time. So we give great parties, we have great events. We’ve been doing that for seven years and the model is really, really successful.

Working with THRIVE and the Silver Living program, I also got asked to engage in other opportunities. I’m just known now for being able to support. I’ve turned into a policy wonk. People will say, “Okay, well if you need to know something about HIV law or whatever, criminalization, whatever, go, Malcolm has all of this stuff.” And just having the time of my life serving the people, and serving myself. And serving myself, right? Someone said, “I needed to create something to save myself.” That’s what I’ve done.

shea: Sounds like you’re staying booked and busy!

Malcolm: My husband says, “So you do realize you retired, right?” [chuckles]

Ronald Johnson, the Chair of the US PLHIV Caucus, and I joke all the time.

I’ll call and say “Hey Ronald, how’s retirement?” Ronald’s in his seventies and he’s “retired,” too. He’ll say, “Oh, it’s wonderful. I’m not doing anything.”

shea: Ah. Just sitting around. Just sitting around, relaxing — changing policy and all.

Malcolm: Yeah, we just chilling. One time, I said, “I think I’ll take up golf.”

shea: Ha! Before I let you go, I did hear you talk about just the lack of spaces and resources for gay Black men who are aging. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about the lack that you see and the needs that you see. I do think in our society, so much of the funding and resources are geared toward young people, whether it’s youth or young adults. So I just wanted to know more about what you see and what you see the needs are, as more and more queer and gay people are aging.

Malcolm: Really it’s a social aspect. I remember being young and in the bar and pointing to an older guy going, “If I am in the bar at that age, please shoot me.” Now, I realize how blessed I am that nobody took me up on that because I’ll be dancing at the club tomorrow, having a good time, but I realized that having that social outlet is important. People see me and say, “No way you’re 65!” People begin to assume certain things when they age. You have to act a certain way. You can’t go out. You can’t do certain things. And that in itself makes you old. It doesn’t help you age, it makes you old.

So when we started working on Silver Lining, one of the things we said was we wanted to get people out of the house, because there’s somebody that’s saying, “Well, I can’t go to a bar anymore because I’m too old,” or, “I can’t go here because I’m too old.” And loneliness and isolation will kill you a whole lot faster than HIV will. So that’s part of our premise and goal — to make sure that people are living their full lives, enjoying themselves. It’s not just about going to a bar or a club. If that’s not you, that’s not you. But as long as you’re not sitting home going, “Oh, I can’t do this, I can’t do that.” I mean, get out. Go to a museum, take a class, do something to make sure that you’re keeping your mind active, your spirit active.

A lot of us don’t have kids and you don’t have children to come over and talk to you. So we want to make sure that we’re getting the people out there and we’re doing the things.

SAGE does a wonderful job because SAGE first seized on the notion that we weren’t supposed to be here this long. Especially If you’re living with HIV — nobody thought that they were going to get to be 65 or 70 years old. We were all supposed to be gone. But we’re here and now as we are getting older, we’re starting to see more and more of this. We’re starting to see more and more groups for older guys, because people realize, “Oh shoot, we’re still here and we got to do this.” It’s just a matter of making sure that people are living their lives to the fullest and they’re doing everything that they can possibly do to make sure that they are happy, healthy, and thriving. That’s what we need most.

shea: Yes! Thank you so much for taking time out of your busy schedule, you’re a busy person, to chat with me and share your story with me. I appreciate it.

Malcolm: Not a problem at all. I love telling these stories because, for me, it’s about letting people know there’s life after an HIV diagnosis. There’s life after 50. There’s life after 65. Get out there and continue to live your life. Don’t slow down. People ask me all the time, “When are you going to just slow down,” and everything else. I said, “I guess the day that they carry me out of here.”

Ain’t nobody trying to slow down! Life is fun. Keep doing it.

Thank you for this! I loved everything about this interview.

this is one of my alltime fave autostraddle series!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

can these continue after feb????

Hard same!

Amazing thank you for this interview!

Really enjoyed this one :)

Thank you so much for this interview, shea (and Malcolm!). I love this series.

This series has been amazing, and this particular interview especially so! Seconding forawhile’s comment that I’d love to see it continue post Feb!

Wow, thank you both for this! What a fantastic story, and really shows how much of a difference one person can make in so many other lives.

thank you Malcolm for sharing so many fantastic stories! thank you shea for interviewing him! and thank you autostraddle for this series!

This was such a great conversation.

This series is great, it’s so good to hear about what’s going on, and get these slices of life in different communities!

Loving this series, and I’m so grateful for leaders like Malcolm!

this series just doesn’t miss!!!!!

I agree!!!

another great interview shea! Malcolm sounds like so much fun, and it’s clear how much you enjoyed talking to him!

I wish I could read 100 more pages about this! Fantastic interview, shea, thanks for introducing us to Malcolm.

this is a great series, I’m excited to see more intergenerational coverage!

Love this piece love this series!!!

This series is incredible – fills my cup every time.

What a fantastic interview! Malcolm seems like a really cool person. Really loving this whole series!

i’m so grateful for this interview. i loved reading about Malcom’s story!

This interview is very wonderful! I didn’t know it’s part of a series and I am looking forward to reading the others.

Thanks for doing this important work, shea!

This is such an inspiring story of resilience and community! It’s amazing to see the impact of intergenerational support in shaping lives.

“Such a powerful and inspiring story! The strength of community and resilience shines through.