feature image via Shutterstock

Welcome to Be The Change, a series on grassroots activism, community organizing, and the fundamentals of fighting for justice. Primarily instructional and sometimes theoretical, this series creates space to share tips, learn skills, and discuss “walking the walk” as intersectional queer feminists.

I was teaching a workshop on campaign plans and strategy to college students recently. It was a small group of students, all from different schools. We were working on a fake campaign for a real issue on one of their campuses to show how the tools worked. It was while plotting a power map on chart paper that one of the students gently corrected me — “accomplices, not allies” — as we were listing potential allied student groups and campus leaders. I paused, said, “Sure, accomplices” and moved on, but it surprised me. What surprised me is the use of accomplice as though it’s interchangeable with ally. It’s not. I should have stopped to think through the complexity a little more, opened up a conversation with the students, but I didn’t.

I do worry about people borrowing from the language of social justice without understanding the history or context. Yes, you may have heard that accomplice is the new word for people in solidarity. It’s become more popular, to the point that diversity and inclusion consultants are making ally-to-accomplice continuum charts and teaching this language in corporate seminars. It’s definitely not a new buzzword for ally, though.

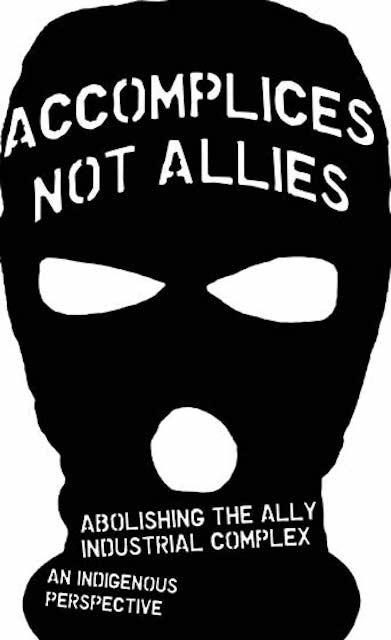

Accomplice isn’t a term that belongs to one group or person. The idea behind it lives in the intersectional framework of Black women and the collaborative model of collective relationships in indigenous cultures going way, way back. One of the earlier recent uses of the word in a social justice context is in the 2014 zine, Accomplices Not Allies: Abolishing The Ally Industrial Complex, An Indigenous Perspective & Provocation. In this zine, the author(s?) write: “Allyship is the corruption of radical spirit and imagination, it’s the dead end of decolonization.” They go on to describe the ways in which allyship has come to be “rendered ineffective and meaningless,” particularly as people have started to claim it as an identity instead of an action.

Accomplice has become a more widely used term in social justice circles and radical spaces. It is not, however, the same as an ally. An ally is someone who stands in solidarity with a group or cause they’re not a member of or that they aren’t directly impacted by. An ally may show up to rallies or participate in meetings around an issue. They may claim allyship simply by aligning their personal beliefs with the rights of others. This is not being an accomplice, nor is it true to the history of the word, “ally.”

Regardless of the current, broad application of the word “ally,” historically it was not a word about social justice. It was a word about war alliances, countries who committed to sharing resources and sharing troops and often sharing a piece of the burden in a war. It was about being in the trenches together, quite literally. That version of an ally in a cause, one who is committed to giving their personal resources and get in the fight alongside folks and take some risks, that’s what I’ve been calling “meaningful allyship” before accomplice as a term gained traction.

Accomplice is, as it sounds, about being complicit in the work (or the crime, in a criminal justice context). It’s about sharing the responsibility and burden of the fight. I like that it implies the danger of getting caught, or, in other words, taking personal risks, giving up personal power and even personal safety in order to be a part of liberating someone else. An accomplice doesn’t just stand with or even just speak out, they do, they act, they de-center themselves actively. Accomplices see the work of solidarity as a verb, not a noun.

As Indigenous Murri artist and scholar, Lilla Watson, famously said, “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

The move towards conflating being an ally with being an accomplice is troubling to me, in that it could render accomplice as “ineffective and meaningless” as some would argue ally has become. The groups and orgs we were listing on that power map during the student workshop, they weren’t accomplices. They were groups we thought might be supportive broadly, but not groups that had shown interest in taking meaningful action or even been enlisted in active support yet. They weren’t accomplices, really…not yet, anyway.

I want to hold to the definitions of accomplice as framed by indigenous writers in Accomplices Not Allies. In the zine, it says:

Download the zine for free at Indigenous Action Media

Accomplices listen with respect for the range of cultural practices and dynamics that exists within various Indigenous communities.

Accomplices aren’t motivated by personal guilt or shame, they may have their own agenda but they are explicit.

Accomplices are realized through mutual consent and build trust. They don’t just have our backs, they are at our side, or in their own spaces confronting and unsettling colonialism. As accomplices we are compelled to become accountable and responsible to each other, that is the nature of trust.

Don’t wait around for anyone to proclaim you to be an accomplice, you certainly cannot proclaim it yourself. You just are or you are not. The lines of oppression are already drawn. Direct action is really the best and may be the only way to learn what it is to be an accomplice. We’re in a fight, so be ready for confrontation and consequence.

I’m not always the accomplice I wish to see in the world. Not to every cause. Not to every group. I always seek to be better, but to be real, there are groups, people, and causes I work and risk a lot more to be an accomplice to. There are other areas where I care a lot, but haven’t built those deep relationships and haven’t risked anything in the work. To me, that isn’t a point of shame. It’s a way to be honest with myself about the spaces and places in which I am an accomplice and those that I’m just a supporter (not even a meaningful ally). It’s not claiming as my own identity that I’m an ally to groups, people, or causes that I’m primarily observing from the outside. Just knowing about something or even retweeting something doesn’t make me an ally, in my own definition of that term. It definitely doesn’t make me an accomplice.

Thanks so much for writing this. I’m not very confident navigating around the language, and sometimes even ideological nuances, surrounding intersectional queerness but I know it’s important to me. I’ll make sure to read the rest in this series.

This was so awesome and educational to read, thank you!

Thank you, this was very educational and useful!

Very thought provoking article. This helped me understand survey answers that were very puzzling. After reading this I understood the answers for one group were based on how they identified not an action. Words have meaning and context changes from generation to generation. Actions speak louder than words or so I thought…

Appreciate this piece.