Art Attack Month:

Art Attack Month:

0. 1/28/2012 – Art Attack Call for Submissions, by Riese

1. 2/1/2012 – Art Attack Gallery: 100 Queer Woman Artists In Your Face, by The Team

2. 2/3/2012 – Judy Chicago, by Lindsay

3. 2/7/2012 – Gran Fury, by Rachel

![]()

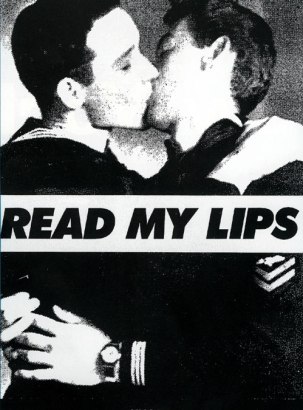

When I was a senior in college, I lived in a little cinderblock apartment on the ground level with two other girls. Our windows let out right onto the street, which was irritating at 2 am on Friday nights, but was absolutely serendipitous when I walked home one night and saw a Read My Lips poster staring back at me from inside my roommate’s bedroom, pasted up inside the window for everyone to see.

I didn’t know it was called Read My Lips at the time, or that it was by the AIDS activist artist collective Gran Fury. I just knew that it gave me a fierce shiny swell of pride to see it in our window, in plain view of the street where frat boys rolled by in their SUVs on weekends, and where no one who lived in our building could walk by without seeing it. I demanded to know where she got it as soon as I got into the apartment; she worked for AIDS Action Committee in Boston, and had come home with a box full of ACT UP posters and paraphernalia. Much of it, like Read My Lips and the corresponding women’s versions, was created by the collective Gran Fury.

Gran Fury existed from roughly 1988 to 1994; with a changing membership that usually came in around ten people, they created some of the most iconic images we have of the AIDS crisis, and voiced the helpless, desperate rage of a generation. Above maybe all else, they were angry. And even though the overarching narrative that they were being fed told them that how gay people felt didn’t matter, that art was useless, that people with HIV and AIDS deserved to die without the majority of the population even having to acknowledge that they were alive, they were determined to make their anger mean something, and turn anger into change. And they did.

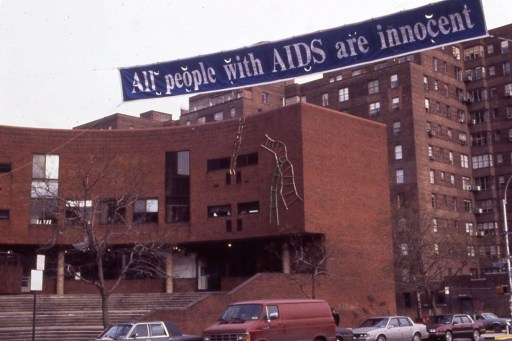

The thing about the AIDS crisis is that, on the whole, many people were committed to not knowing it was happening. Images and narratives of AIDS, and the people who lived with AIDS, simply didn’t exist. The “photo that brought AIDS home,” and which was for many Americans the first time they really acknowledged the epidemic, wasn’t published in LIFE until 1990. Gran Fury created a banner telling all of Manhattan that ALL PEOPLE WITH AIDS ARE INNOCENT in 1988. They were angry that anyone felt gays and AIDS victims deserved to die and to be forgotten, and they maintained that anger was necessary to our survival.

When I came home to find our little apartment, perpetually littered with the Smirnoff ads my roommate loved and my dirty dishes, made into a tiny outpost of queer history, it felt perfect because I was angry, too. Of course I can’t lay claim to the huge, deafening pain of the AIDS crisis; I would never try to. But I was angry that I was working two jobs and still broke and in debt and that all of my friends were broke and in debt and there was nothing we could do. I was angry that the brilliant queer women I knew were desperate for waitressing jobs or AmeriCorps positions while the straight men I went to college with were getting jobs at Washington think tanks and banks on Wall Street. I was angry about the men who would leer at my friends and I outside of bars, slurring “That’s so hot” if two of us were physically affectionate in any way. So yes, “read my lips” felt like the right thing to say. Two men in uniform with their lips locked felt like the right message to send to the boys who left broken beer bottles outside our apartment. My roommate didn’t have any Read My Lips posters left, but I got one that said “I Am A Mannish Muffdiver Amazon Feminist Queer Lesbian Femme and Proud!” and that felt right too. It’s still above my bed today.

Gran Fury began with wheat-paste posters like Read My Lips and later on had major collaborations and installations with galleries and museums, and much of their funding came from respected art institutions and museums like The New Museum of Contemporary Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, Los Angeles’ MOCA and Creative Time. They were in the bizarre position of being taken fairly seriously by the art world while their message and the fundamental basis of their existence still seemed to be totally inconsequential to the world at large. Their name was a reference to the model of unmarked police car popular with the NYPD, but they were simultaneously lauded (and financially supported) by some of the most important New York art institutions. Gran Fury dissolved after a central member, Mark Simpson, died of AIDS in 1996. In the group’s farewell essay, “Good Luck… Miss You,” they talk about how the rage that fueled their art and their movement seems to have been allowed to peter out, and how it might be worth questioning what kind of art we’re making if there’s no anger in it.

Our culture is run on carefully crafted words and images. They are given tremendous authority, and have the power to shape society’s responses. It is worth noting that the images which have endured through the AIDS crisis are not ones of activism. Rather, they are symbols of remembrance and reprieve: quilts, ribbons and angels. The symbols and symptoms of our acceptance of AIDS, our acceptance of death. Acceptance may be an appropriate response to the tragedy of AIDS. It is not a political response.

In an interview with Artforum, though, some of the later Gran Fury members talk about one of their last pieces, The Four Questions. For a group organized largely around the idea of anger as a driving force, the piece that they describe as being meant as their farewell is hard to describe as anything but truly, deeply sad.

ARTFORUM: Okay, let’s begin with a work that seems appropriately sad. Ten years ago a few of you in Gran Fury made a poster with four questions, the last of which

was, “When was the last time you cried?” Was that the final work done under the auspices of the group?

LORING McALPIN: Well, after that we did the flyer Good Luck . . . Miss You for “Temporarily Possessed” at the New Museum. That was meant as our farewell.

ARTFORUM: That was 1995. You did the four questions in ’93. Do you remember the other three questions?

AVRAM FINKELSTEIN: “Do you resent people with AIDS? Do you trust HIV negatives? Have you given up hope for a cure?” The conversation leading to that work was largely driven by Mark Simpson. We were grappling with a problem we had at that later stage—trying to put very complex things into a very concise text. This work was a response to our frustration at being unable to articulate the complexity of the issues. We decided to just go bare bones and say how we felt, which had never been our primary focus.

Most of Gran Fury’s work was aimed at what felt like (and often was) an unfeeling public; the gay community didn’t need anyone to tell them that “The Government Has Blood on its Hands” or that there was one AIDS death every half hour. In a lot of ways, much of what Gran Fury did was meant to function as advertising for the general population, except instead of selling Coke or sneakers they were trying to sell the idea that you should care if people around you are dying needlessly. But The Four Questions, in Loring McAlpin’s own words, was “…addressing a different audience. It was really directed toward our own community. We were trying to acknowledge something but not judge it, to ask, “What’s happening now? Where did our anger go? What are we going to do?”

The thing is, of course, that there’s a lot more than four questions. There are a lot of things we’re trying to ask ourselves, and each other. When was the last time you cried? If we’ve stopped crying, is it because we’re not angry anymore, or is it because we’re so angry that if we started we’d never stop? The AB101 riots happened in 1991, just a few years before this moment. 50,000 people marched through the city that night. Two years later, a group of people who were losing a colleague and one of their best friends were asking us if we had given up hope. What do the last 15 years of gay activism and art tell us about that?

There’s a lot of skepticism about the degree to which art can change the world we live in. Probably there always will be. One thing that we can say with some authority, though, is that art is one of the ways in which we talk about how we feel, to each other and also to ourselves. When no one else on Earth wants to hear about how angry we are about what they have done to us, art is the way that we find to say it anyways, to ourselves even if no one else is listening. And when we’re trying to navigate the impossible, unbearable space in between and encompassing anger and sadness and helplessness and rage, we rely on art to give us a language in which to do so. This is what we owe ourselves when no one else is interested in acknowledging all the things that have been taken from us. Not just as an emotional or cultural exercise, not just as an idea, but as a real and concrete part of our offensive defense in a culture that’s declared war on us and our loved ones. The art we make about our lives is part of what makes them worth living, but also part of how we defend our right to our lives in a world that doesn’t make anything easy for us. I’m grateful to Gran Fury for the constant reminder that honest anger is something necessary and valuable, that we do not have to go quietly, and also fuck you, because we don’t deserve to have to go at all.

Check out a digital gallery of Gran Fury’s work courtesy of the NYPL, as well as their archive at the Queer Cultural Center.

The art we make about our lives is part of what makes them worth living, but also part of how we defend our right to our lives in a world that doesn’t make anything easy for us.

Yes.

A thousand times, yes.

everything about this is really beautiful. beautiful, but also sad.

i want a Read My Lips poster.

This might be premature of me, and if I were more eloquent I’d say more, but this article could end up being my favorite in the series.

Rachel, I always love your writing, but this really stands out. It’s beautiful. Thank you for writing it (and everything else).

that last paragraph is one of the most beautiful and true things I’ve read in a long time.

Autostraddle, I think this month may make me love art the way pure poetry month helped me to love poetry.

!!!

I don’t know what else to say.

Rachel, I love this. Thank you.

Beautiful, beautiful writing.

“One thing that we can say with some authority, though, is that art is one of the ways in which we talk about how we feel, to each other and also to ourselves. When no one else on Earth wants to hear about how angry we are about what they have done to us, art is the way that we find to say it anyways, to ourselves even if no one else is listening. And when we’re trying to navigate the impossible, unbearable space in between and encompassing anger and sadness and helplessness and rage, we rely on art to give us a language in which to do so. This is what we owe ourselves when no one else is interested in acknowledging all the things that have been taken from us.”

wow. This is so beautiful I almost cried. Thank you for the beautiful and informative article

argh! my comment didn’t go through. Stupid internet!

“art is one of the ways in which we talk about how we feel, to each other and also to ourselves. When no one else on Earth wants to hear about how angry we are about what they have done to us, art is the way that we find to say it anyways, to ourselves even if no one else is listening. And when we’re trying to navigate the impossible, unbearable space in between and encompassing anger and sadness and helplessness and rage, we rely on art to give us a language in which to do so. This is what we owe ourselves when no one else is interested in acknowledging all the things that have been taken from us.”

^this. Thank you for writing such a beautiful and informative article. It almost made me cry

This was a wonderful reflection on Gran Fury, and some queer art from the 80s and 90s.

The “I am…” poster you have is by the art collective Fierce Pussy, from the same time as Gran Fury and ACT UP. Not only do they have an awesome name, but their work was cleverly confrontational, the “I am…” posters and others wheat-pasted across NYC. Don’t forget about them, and give credit where credit is due!

thank you! i actually couldn’t find who to credit that to, because somehow that wasn’t as easy to find via the internet/activist records, so i really appreciate that!