Maybe I just live in my own gay hippie bubble, but I feel like the average queer person I meet cares more about the environment than the average straight person that I meet. However, that queer environmentalism never seemed to be reflected, even a little bit, in my environmental studies coursework. Sure, we heard from a variety of voices, people who spent their whole lives working to preserve, conserve and clean up the world around them. The most prevalent? John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Gifford Pinchot, Theodore Roosevelt — voices that are white, cis, male, straight and a hundred years old. Rachel Carson seemed to be the outlier, the only woman widely heralded for her work in environmental justice.

Still, these aren’t modern voices. Today’s specific issues — like climate change, sea level rise, pollution and habitat fragmentation — need new voices, preferably voices from different parts of the population than we’ve heard from in years past.

When I went looking for these voices, I heard about so many awesome projects: some abroad, some here in the U.S., some addressing issues of sea level rise, others addressing natural disaster risk reduction, others still with garbage management systems. Let’s all just take a moment to sit in awe of the work that these queer women have done and continue to do.

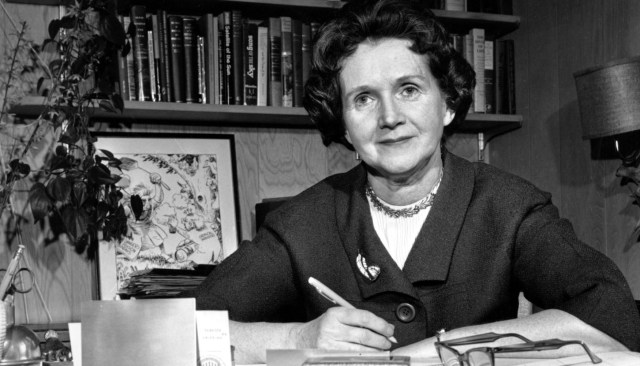

Rachel Carson

Photo credit to University of Nebraska.

Rachel Carson, founder of the modern day environmental movement, may have been a queer woman! She herself never married and she had an intense, long-term friendship with Dorothy Freeman. The two met in 1952 when Carson moved to Freeman’s community on Southport Island in Maine, and thus a beautiful friendship began. After spending the night with Freeman in 1953, Carson wrote in a letter, “My dear one, there is not a single thing about you that I would change if I could!” Some of the letters between Carson and Freeman were published in 1995, but the two of them destroyed many of their letters to protect the more private parts of their relationship before Carson died of breast cancer in 1964.

Professionally, Rachel Carson was a marine biologist. She was also a talented writer and editor. In 1962, she published Silent Spring, a book that looked at the harmful overuse of pesticides that she believed was causing plant and animal die-offs and cancer in communities near farms. This pretty much pissed off the pesticide industry, but she made enough of a stink to testify in front of Congress in 1963. She asked Congress to create new policies protecting humans and the natural world. Carson didn’t live to see the creation of the EPA, the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act or the boatload of things named after her, but her writing and her voice was instrumental in their creation.

Mahri Monson

Mahri Monson is a bisexual woman who works as a program analyst for the EPA and lives in Washington, DC. Monson, along with other EPA employees, worked for years to create a policy concerning transgender and gender nonconforming folks at the EPA. The policy, signed off by then-EPA administrator Gina McCarthy, provides a guide on transitioning while working at the EPA and reiterates that discrimination based on gender identity is unacceptable.

“I do think that making sure EPA’s workplace is inclusive and as representative as possible of the American public that we serve has a secondary connection to environmental justice, in that if we’re made up of a diverse, representative, inclusive workforce, I think that gives us the best chance to serve all of our communities in this country,” Monson told Autostraddle.

Monson has researched ways to make low-income communities more resilient to climate change. She has also worked to enforce the Clean Water Act. Among other things, she did this by supporting green infrastructure to help manage sewer overflows. This happens with communities build constructed wetlands or green rooftops to deal with sewage that spills on its way to water treatment plants. This green infrastructure can collect pollution, keeping it out of waterways. You would hope that sewer overflows wouldn’t happen that often but they actually happen 23,000 to 75,000 times every year. Low-income communities who live near waterways generally face greater negative impacts if sewer overflows happen.

“I feel very strongly that everyone deserves to live in a healthy, clean environment and to have access to clean air and clean water,” she said, “and I think if a healthy environment is not equally accessible to everyone, that’s not justice.”

Rebekah Paci-Green

Photo Courtesy of Western Washington University/Rhys Logan

Rebekah Paci-Green’s drive to help the environment isn’t based on saving the environment in and of itself, but rather helping people live in their environments. She works as an assistant professor at Western Washington University, and she is also co-director of a non-profit that works to decrease damage to school buildings in the case of natural disasters. If communities don’t work to coexist with their environment, she said, the impact on children is particularly great.

“We tell them they have to go to school, but then we don’t necessarily provide a safe place for them to do so,” Paci-Green told Autostraddle. Schools might be unsafe because the actual buildings are unsafe or because the school fails to adequately address bullying or because evacuation plans for natural disaster fail. This can result in horrible disasters.

She once spoke with the mayor of a town in Japan following the tsunami in 2011. When the tsunami hit, the principal was away from the local school. There was a plan in place for everyone to evacuate over a bridge, but in the absence of the principal, some faculty suggested that they take the students up the steep hill behind the school, which at this point was one big mudslide. Eventually, they decided to take the predetermined evacuation route over the bridge, but they took so long discussing it that they ran out of time to safely evacuate. They were on the bridge when the tsunami hit, and they were swept away. All but a handful of students were killed.

“I was talking to my students about this, and I actually almost starting crying in front of 28 students,” Paci-Green said. “I had to stop myself and say, ‘Okay, I can’t talk about this anymore. We gotta go back to talking about probability.’ But. That’s why I work on this stuff.”

Judi Brown

In grad school, Judi Brown completed a project in Kenya working with women entrepreneurs. She spent a month and a half interviewing women to find out what they actually needed to make their businesses successful, and what she found was that they needed access to sustainable products. For example, rainwater catchment systems could allow the women to gather clean water, or solar-powered cell phone chargers could allow women to charge their community members cell phones. Without these products, women would have to travel far away to a city to get water or to charge their phones.

Now, Brown is a partner and chief impact officer for CivicMakers, an innovation and engagement firm. She teaches about sustainability-focused management at Presidio Graduate School, and has a project coming up to help implement Fremont, California’s Smart Cities Initiative.

In college, she struggled to find a space where she could be open about her queerness and also work in sustainability. “I often felt like the sort of queer alien in the sustainability space, or the sustainability alien in the queer space,” Brown told Autostraddle.

Brown is also the vice president of the board of directors for Out 4 Sustainability, a non-profit that seeks to mobilize the LGBTQ community to partake in environmental action.

“We often host events where we’ll plant trees or work on farms or do beach clean-up efforts,” she said, “but mostly it’s about getting people together who identify as queer and allowing them the opportunity to be working on projects together and create some visibility around that.”

Lindi Von Mutius

Photo credit to the Environmental Defense Fund

Lindi Von Mutius has always been driven to environmental justice because she grew up in low-income communities where environmental problems really affected her community. She’s also a board member for Out 4 Sustainability, and she works as director of program management for the Environmental Defense Fund. She’s hoping to start a side project with some of her EDF colleagues and law school friends to help coastal communities deal with natural disasters.

Following the Civil War, communities sprung up in floodplains. These were freed slaves, war veterans, and sharecroppers who didn’t or couldn’t obtain proof of their right to the property. Fast forward to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Some neighborhoods bounced right back, rebuilding the damaged property — predominantly white communities. Some historically black communities faced a different fate. First of all, they bore the brunt of the damage because, physically, they were in vulnerable areas that no one else had wanted a hundred years prior. Then, unable to prove their property rights, they couldn’t obtain help from FEMA or other disaster funding.

“Now, you have a vibrant community right there, but if it gets flooded or erased by a natural disaster the way that all these communities in New Orleans did, how do you rebuild? And how do you deal with that proactively?” Von Mutius told Autostraddle.

Von Mutius is hoping she can get a grant for her project, which she’ll use to build infrastructure to physically protect these communities from natural disasters, as well as helping secure their legal right to the land so they can get disaster funding down the road.

She said that as a whole, she doesn’t feel like the only queer person, but that queer diversity and race diversity have both been pretty terrible in places she’s worked. However, she said environmentalists have been generally accepting of her bisexuality.

“There’s something to be said for the hippie environmentalists,” she said. “They’re pretty okay with inclusion. They just might not have it themselves, but they’re very accepting of it and very tolerant and very open.”

Rikki Weber

Photo credit to Earthjustice

Rikki Weber is a litigation assistant and office manager for Earthjustice, a non-profit environmental law firm. She said although Earthjustice gets a lot of attention for the national work it does, a lot of the work is done at the local level. This involves advocacy and engaging with communities so Earthjustice can provide the appropriate services.

“The one thing that always comes back to me is how I’ve seen the how power of the law affect change, like for the queer movement,” she told Autostraddle, “and I see how the law affects our environment and our ability to mitigate harm against it and against communities, especially marginalized communities, which queer people are a part of.”

Weber recently started a group with one of her colleagues for LGBTQ+ employees of Earthjustice. Although it’s new, she hopes that the platform will allow discussions on intersectionality, especially how a broad range of identities factor into someone’s identity as an environmental justice worker.

“The reason I do this work is because I belong here, too. We belong here,” she added in an email. “Environmental justice is for all people and achieved by the people. As a queer woman of color, as a person whose layered identities are often pulled apart, compartmentalized and marginalized, I have made it a point to insert my whole identity into my work. I hope that my visibility and the visibility of other LGBTQ+ identified people helps strengthen the environmental movement by allowing us to express our differences and use them to find the commonalities in the ways that we can disrupt the systems that were built to oppress us.”

This is so good! Here’s the link to one of the organizations, Out 4 Sustainability: http://out4s.org/

I’m also working as a sustainability scientist and the ideas shared here about the importance of finding and connecting with our communities to make progress ring true to me.

Thanks for sharing that link and thank you for your work!!

All the yes! Thank you for posting this… and would love to see more like it on AS!

(Said the totally biased nature-based preschool director.)

This was so inspirational!

Thank you for this article- would love to see more on this topic!

This was awesome!

Wow, this surely is quite a list! But hmmmm I feel like many queer women and non binary folks I know have a rather shallow way of caring about environmental issues? Like, will buy organic food, but will not give up their precious flights to Berlin (I’m European) or even San Francisco several times a year. ..

This is great! Such inspirational and important work

Thanks for bringing this group of people to my attention

This article was not only informative but necessary. The work these women do day-to-day often go unnoticed and it’s great to see them so eloquently honored. Not only that but calling attention to the issues they face as queer women in their field and workplace. Most all of us can identify with that, and as someone who works in a very white male-dominated field, I felt deeply connected to these amazing women. It’s important that queer women be heard, and after reading about the work and perspective these women offer to the field, the title of this article really hit the nail on the head.

This is so excellent. Thank you!