At 27, I came out as Korean-American. I was always Korean, of course. I checked the “Asian” box when filling out a form. My ethnicity was written on my face in the shape of my eyes and my small flat nose. But until a few years ago, it wasn’t an identity I felt connected to. There were many identities that came first — poet, bisexual, queer, feminist, activist, organizer, fattie, vegan. Being Korean was a fact, but not an identity.

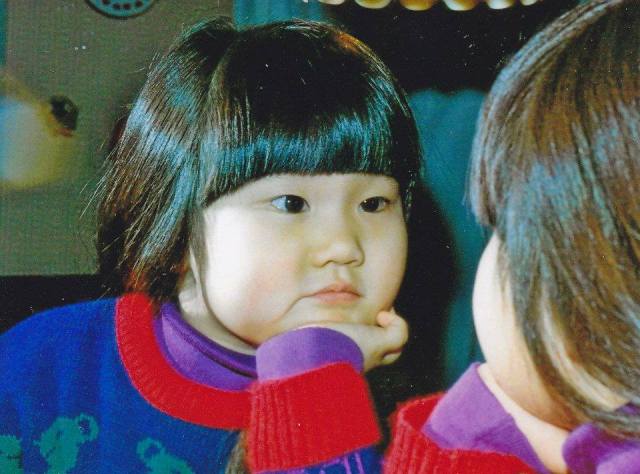

I met my parents in 1984, on June 15, the day I arrived in the continental U.S. on an airplane and was placed into my parents’ loving arms. I was 17 months old, my thick hair clipped up in a messy topknot. My parents scooped me up and brought me home to the small, rural town in Western New York where I grew up. A few years later, we adopted my sister, who is three years younger than me.

My dad is Italian and my mom is Swedish-German. My sister and I were pretty much the only Asian kids in our school or neighborhood. We are immigrants, though we were both so young when we came to America that we don’t remember anything about Korea. Before identifying as Korean-American, I strongly identified as “American” in a big-tent-melting-pot-kind-of-way. From talking to other Korean adoptees, I’ve found this is a super common way for international adoptees to identify. When I was really little, I told classmates that I was 1/4 Italian, 1/4 Swedish, 1/4 German, 1/4 Korean and 1/4 American. I knew I was adopted, but I didn’t quite grasp how ethnicity worked… or math. I was, like, 5, ok?

To some degree, I am all of those identities. I know much more about Italian food than Korean food. I took German for eight years (and speak it very poorly). I was the only one in my family who preferred chopsticks when we went to the Chinese restaurant, which I taught myself how to hold from the instructions printed on the chopsticks wrapper sometime circa high school. I definitely picked up mannerisms and quirks from both my parents. People say I sound like my mom on the phone.

I had an awesome childhood. My parents were always there for me and I knew I was both wanted and loved. But being the only Korean kid for all my formative years had two effects: 1) I was made to learn how to stand up for myself and be strong in my convictions from a young age, and 2) I felt extremely disconnected from my race and ethnicity in ways I didn’t even understand until I was much older.

My peers were generally nice to me as a little kid, but some were jerks. In kindergarten, during the first week of school, a white boy from another class made fun of me in the hallway, pulling the corners of his eyes back to imitate mine. I came home that day crying. Being poked fun at for the shape of my eyes forced me to learn what it was to be “othered.” It was a hard lesson. My parents had taught me that everyone is equal and deserves to be treated equally. Our home was mostly colorblind. At 5, I didn’t have a context for oppression. My parents always encouraged me to be proud and said there was nothing wrong with being different, something I thank them for (though they probably didn’t expect it to lead to my coming out as bi/queer 12 years down the road). However, I didn’t understand until I was made fun of that looking different meant being treated differently. I didn’t understand that everyone is, in fact, not equal.

I can still tell you about every Asian in my high school, every black and Latina kid in my grade level. I had mostly white teachers, all white friends, all white crushes. I listened to the same music and wore the same clothes and had the same hobbies and celebrity idols as my white friends. If I am honest with myself, I can say that I was more attracted to white people and that I used to think that Asian people were less pretty. I thought I was less pretty.

On top of all that stuff that comes with puberty-time like low self-esteem and friend drama and crushing self-deprecation, I thought the reason I couldn’t get a boyfriend (a girlfriend was, like, not even in the realm of possibility for me at that time) was my eyes and my flat face. Because Asian girls weren’t pretty. I vividly remember laying on my bed in one of those classic teenage angst moments, crying because even if I lost weight or was popular, I couldn’t change the way my face looked. I couldn’t be attractive. It wasn’t something I talked about with my friends — all of whom were white — because it was a deeply personal self-hate. I didn’t come to see this internalized racism for what it was until way later.

I actually convinced myself that I looked “less Asian” than other Asians, that my eyes were slightly more round. When I compared my face to the faces of Asian women in magazines (few though they were) and even to my sister, I was sure my eyes were slightly more white-looking. I asked my high school friends if I looked less Asian to them. They said they didn’t see me as Asian or white, that I just looked like myself. My friends and I played at colorblindness without realizing how loaded that was. Maybe they sensed that I wanted to be told I looked a little white and played along. Even today, when I look in the mirror, I don’t see myself as Korean. I logically know I look Korean and I wish I could see myself that way, but I’ve implanted this other version of what I look like in my brain. Unlearning it is going to take a long time.

I have this sort of weird unofficial passing privilege in that I grew up in white spaces, with white people, identifying as kind-of-white, in a middle class American family in a small town. I am often the only person of color in the room, but it isn’t uncomfortable to me because it’s my normal. I know how to “act white” because that’s just how I act. In college, I joined the Asian Student Association for a bit. I felt way more out of place there than I ever had in an all-white space. I awkwardly tried to contribute and ended up becoming closest to the one white ally in the group. I didn’t understand the cultural jokes and norms people talked about. I also just felt out of place physically. I was the only fat girl. I was the only feminist and the only queer. I just felt like I was taking up too much space — too loud, too big, too much. I quit after one semester. I decided that I just wasn’t very Asian and that was OK.

Simultaneously, I was living into other identities that felt very authentic. I was the co-director of my campus Women’s Center. I was out as queer and friends with other queer and feminist people. I went vegetarian and then vegan. I was anti-war and pro-choice and anti-sweatshop and lots of other labels. Claiming an identity was super important to me. I had t-shirts that had those identities printed on them in bold white letters. But I didn’t identify as a person of color. That was not, in my opinion at that time, my struggle. I was anti-racist, but I didn’t really think it applied to me as much as to other POC with, what I considered, more authentic oppression.

Years later, I was talking to another feminist Korean woman about this after a conference in NYC. We were on the subway, on the way to dinner. As I described my feelings about not strongly identifying as Asian, she listened quietly. When I was done, she said, “But you are Korean. Your experience is the experience of a Korean person. Just because it’s not like my experience doesn’t mean it isn’t a valid Korean experience.” Boom. At the age of 27, I suddenly realized that being Korean didn’t have to mean having Korean parents and eating kimchi and knowing K-Pop artists. That I ever thought that suddenly felt really stupid. We talked a lot at dinner that night and I came to realize that I had a lot in common with other Korean-Americans, both adoptees and those with biologically-related Korean parents. In fact, there are so many Korean adoptees who grew up in American households with parents of a different ethnicity that there is a whole cultural/ethnic identity — KAD (Korean International Adoptee) — built for and around Korean adoptee experiences and culture.

By claiming a Korean identity, I let myself acknowledge that I’d faced oppression and racism. I realized that I identified with the collective “we” of American culture and history because I never had access to anything else. The history we learn in public school is a white-washed, Euro-centric version. My ancestors did not descend from Europe, but I’d bought that story, as many kids of color do.

Every makeup tutorial I’d ever read in Seventeen or Teen Cosmo or Sassy didn’t work on my monolids. I couldn’t find a foundation to match my not-pink-not-beige-not-brown skin tone. I was affected by the lack of Asian representation on TV, in magazines, in the music industry. I have been told innumerable times by strangers that my sister and I look like twins when we couldn’t possibly look more different. When I stand next to other Korean women of my approximate age, it is assumed we are sisters. People just randomly speak to me in Korean or ask me to say things in Korean, forcing me to awkwardly tell them I only speak English (and very poor German). I’ve had more than my fair share of people and partners who exoticize me, sexually or platonically. At the end of the day, I still look in a mirror and can’t see myself fully, even though I’ve tried to unlearn my white-washing of my self. By escaping into my passing privilege, I erased my own identity.

Over the next four years, I started identifying strongly as Korean-American. After a quarter century of joking about being a Twinkie, yellow on the outside, white on the inside, and saying things like, “Well, I’m not really Asian,” it felt like coming out all over again. Everyone has always looked at me and thought of me as Asian, but I’ve only just recently started thinking of myself as such. Strangely, even with the drama and difficulty of coming out as bi/queer, it was harder for me, personally, to come out as Korean.

I used to be more comfortable in a room full of white people than a room full of POC. While I can still pass in an all-white crowd, I notice now if I’m the only POC. I am infinitely more comfortable in POC spaces, because I finally feel I belong there. Actually, now I’m that person in POC spaces gently prodding for more diverse representation — especially of Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American people.

My partner and I are talking about and planning to have a kid. In the next year, I hope to be knocked up. I never planned to have kids before and I definitely always thought I’d adopt (from Korea, but turns out that is not legal yet), so I hadn’t thought much about having biological children. Once we made this decision, I was surprised to find that I had a lot of feelings about having a kid who looks like me. I have never, ever met anyone who looked like me. It is beyond what I can imagine. It kind of makes me freak out a little if I think about it too hard. I also think about wanting to pass on some sense of a cultural heritage to my kid, who will be at least half Korean. Honestly, I’m still learning about Korean culture myself, but I would like my future kid to have the option of accessing that cultural history. Maybe I’ll send them to Korea School, if I can find one that is not religiously affiliated.

I have had to come to terms with the fact that now that I have conceptualized a future kid who looks like me, I really want them in my life. It is so weird for me, wanting children at all, let alone biological children. My partner, who will be the non-gestational parent, will not be biologically related to the future kid. I’m not biologically related to my parents or my sister. Biological relationships have never been important to me because my family is not about shared DNA. Hell, if queer people know anything, it is that family is created through love, not blood. I’m surprisingly and suddenly very excited about meeting this future person who will have bits of my very-Korean face. I hope I can raise them to be tenacious and strong, as my parents raised me, and to help them understand that their very queer family story is a Korean-American experience, too.

Thank you so much for this—beautifully written, challenging, and loving piece. As an adoptee myself, I always so appreciate hearing other adoptee voices.

And this part personally resonated for me: “I was surprised to find that I had a lot of feelings about having a kid who looks like me. I have never, ever met anyone who looked like me. It is beyond what I can imagine. It kind of makes me freak out a little if I think about it to hard.”

This is just one of those things that non-adoptees can’t really understand (and often dismiss). It’s always, always been at the forefront of my adoptee experience, and I can imagine that for transracial/transnational adoptees, it’s even more so.

Also: omg, SO CUTE! That first picture is especially painfully adorable.

Yeah, I was a pretty adorable kid. I’m not going to lie.

Yes, I never really thought too hard about the fact that no one looks like me. It’s just a fact of my life. When it hit me that there would be, in the future, someone who has by DNA, it hit me unexpectedly hard.

One of the most awkward part of being an adoptee is hearing other people’s birth stories and family genealogy stories. I can appreciate hearing them and don’t have any resentment about hearing them, but I have nothing to add to the conversation. It is outside my realm of experience. I was born…on a plane? My family’s history is important to me, but it’s not the history of my ancestors, so…you know. I don’t look like Great Aunt Sue.

Thank you for sharing this. I don’t pass for the typical image of a person of modern Iranian/Persian heritage(though I have hair issues like one), and more of old Caucasian heritage. But, you now have me thinking, maybe it’s because I look less like the people on that Bravo show(or other middle easterners in generally) I am a bit more disconnected.

*Side note: I can pass for at least 3 different ethnicities, so I am generally not seen as the ethnicity I am.

Oh man, I pass for everything – except what I actually am. Zanzibar? New Zealand? Sri Lanka? Suuuuuuure. Bangladesh or Malaysia? “You don’t look Malaysian”. FFS!

It’s the same for me, I would have never guessed, and then I would give the quick explanation that in the olden days we were more Caucasian looking and less what you see on tv now.

Passing privilege can be damn awful. It disconnects us from our communities, but still leaves us outside of whatever normative group we are assumed to be a part of.

As a power femme, I see a lot of similarities between my femme passing privilege and my weird middle-class-white-ish passing privilege.

Well for me it’s less passing as American/European white, and more of Slavic white(I get asked many times if is speak some dialect of Russian).

I feel like maybe we should just stop asking each other these questions, unless, for some reason, they really matter. Like…I can’t think of a reason it would be appropriate, actually.

Seriously, just stop.

The worst is when it comes from other POC and I’m like, “You should know better!”

I agree, in most case I just say maybe as I keep on shopping.

OMG I feel you so hard on so much of this. I wasn’t an adoptee – I was born to Bangladeshi migrant parents in Malaysia. I was never really brought up in Bangladeshi culture, and yet had to both be forcibly assimilated into Muslim Malay culture (given that my family was Muslim) and still be ostracized because we weren’t “doing Islam right” or we were “Bangla” and therefore distrustful. Hell even now the progressive lefty political parties use anti-Bangladeshi sentiment in their campaigning.

Yet because my exposure to Bangladeshi culture was super limited, I never really connected to much of it. I go to Bangladesh and I am an instant foreigner. Like you said, me being Bangladeshi was mostly a fact rather than an identity. I was pretty strident about Bangladesh rights in Malaysia, but my family had class privilege that marked us as different from most other Bangladeshis in Malaysia (who came as hard labor), so even then we were unrelatable to anyone.

I understand Malaysian culture better than most other things, but in there I was treated as an outsider – especially since my politics & sexuality & interests also marked me as somewhat Western. But whenever I am in the Western world I stick out for being brown. I’m even too brown for queer people.

I’ve always had to deal with racism, but it was in a very different context, where Whiteness wasn’t as prevalent and a different race took up the Dominant Race role. I tended to fit in more closely to white people culture, like you mentioned. But I still stick out some, still get the stupid comments and the assumptions.

Often I wished I was an adoptee or mixed-race or something, because those stories speak more to my experience than stories of POC or diaspora or whatever. It would make a lot more sense.

I’ve only started really exploring my Bangladeshi background more, through stories and art. I’ve been meeting a lot of other Bengalis here in the Bay Area of all places – though most of them are from West Bengal, but close enough.

Sorry, rambling…but so much of your article spoke to me, especially the paragraph about “weird unofficial passing privilege”. That entire thing – YESSSSS.

(Speaking of weird unofficial passing privilege: the moment that defined this for me was when I was at secondary school and the prefects were divided along racial lines on who they would choose as Head Girl. Being Bangladeshi and Muslim, I was allowed into both the Malay-prefects-only meeting and the Non-Malay-prefects-only meeting. You’d think that this would make me the ultimate candidate, but nooooo…can’t have Banglas ruling over us…sigh…)

THANK YOU for sharing all of this. I felt a lot of what you are saying. Though our stories are different, they are similar in that they are stories of displacement, but literally and culturally.

Do you feel like interpreting your cultural heritage through your own lens has been important for you? I know, for me, writing about it and getting tattoos (a very not-Korean way of commemorating this journey) related to my identity has been a part of connecting to my Korean-ness. Discovering Korean feminists and Korean poets has played a big role for me, too.

(You can be the Head Girl of this thread. Congrats.)

“I have this sort of weird unofficial passing privilege in that I grew up in white spaces, with white people, identifying as kind-of-white, in a middle class American family in a small town.”

guh, this is the realest. this whole essay is amazing and resonant, but that paragraph just really gets at the weird racial displacement that I felt for a long time. even now, when I’m hyper aware that I’m often the only POC in the room (in an industry that has a lot of Asians, but not in the spaces I want to be at), I’m also…comfortable? It feels familiar, and familiar is comfort, in a way, though I’m trying to get out of that line of thinking. Thanks for this, KaeLyn, and thanks also for sharing your adorable baby pics

Yeah yeah! For so long, when I was around other Asian people, I felt like I was suddenly really visible and it kind of scared me. I was, like, afraid they would see that I wasn’t really Asian if they looked at me long enough. White people were just familiar. If they asked me dumb questions, I knew how to answer them. If another Asian person asked me about my culture or spoke to me in Korean, I felt like I was failing in my answer. FINALLY getting over this and using my weird unofficial passing privilege for good by trying to open doors for more POC to be at the tables that I get invited to.

Thank you so much for this piece KaeLyn! My mom is a Korean adoptee and I was essentially raised white because my mom didn’t have a Korean identity until recently either.

Growing up hapa (Korean/Welsh) I constantly struggled with my racial identity, and when I finally felt like I’d learned to accept my racial identity as mixed, my girlfriend told me that despite how I identified, the world would still only see me as Asian *eye roll*. Funny how although we’ve hit a point of asking preferred pronouns and trying to accept the concept of gender fluidity, we still see race as a static, 1-drop-rule. Best of luck with the pregnancy and child-rearing!

Thanks! Loving side-eye to your GF on that comment. :)

THIS IS SO POWERFUL AND AMAZING, KAELYN. Thank you for sharing your experiences with us. I could imagine this journey is very difficult and troubled and conflicting. I follow a few KoreAm adoptees and activists on Tumblr and what I read from them is so sad but beautiful and real, it just all hits you in the gut. Power and grace to you in your quest in self-discovery and identity as defined by you!

I also wasn’t adopted so my experiences are nothing like this, but I grew up being the only Black-passing member of my Dominican family in America. Now as an adult I know that I look exactly like my mother and a lot like my father and my baby sister, so yes, I am very much a part of my family, but when I was little all I saw was my skin color being so much darker than everyone else’s. When we lived in Rochester and we’d travel to Canada, I was so afraid I’d be detained at the border because I didn’t look like I was my parent’s child since I was too dark! It was a sincere fear for me! Growing up and having other people, including Latin@s, doubt and question and poke at my ethnicity, then have them poke and question and doubt who my parents were, I legit just believed I was adopted for the first 7 or so years of my life. I just didn’t think I belonged anywhere, as an American, as Latin@, as my parent’s daughter or my sibling’s sister-everyone including family othered me and it was just so strange. I was always in super white spaces so similar to you, I am used to being the odd-one out and still can code with them and come off as accessible or safe when necessary, but I never felt assimilated or accepted in them nor did I ever like being told I was “One Of The Good Ones”-while I struggled with accepting my Blackness, I never for one second was not proud of being Dominican and always sideeyed white people lmfao, I never identified with them. I always felt antagonized or on edge in those spaces because white people were either complete assholes to me or just like, pretended I wasn’t there because they didn’t know what to make of me. So I just floated on the outskirts of every racial group, too white or at least not Black enough for Black people, too Black for Latin@ and White and Asian people, it was weird. It is still weird. My friends’ group is this strange hodgepodge racially (though still primarily white, though my immediate friend’s group is primarily WOC), but everyone is super fucking cool, so for that at least I am happy.

I forgot for a second that you grew up in the Roc. Rochester is, like, a shining example of diversity compared to where I grew up. However, it is really racially divided, as you know, there is a big emphasis on putting people into boxes in these parts. I can totally imagine feeling on the outside of every racial group or community in these parts.

Border fear is real in these parts, too. We are in the Constitution-free zone (northern border) after all.

“I can still tell you about every Asian in my high school, every black and Latina kid in my grade level. I had mostly white teachers, all white friends, all white crushes. I listened to the same music and wore the same clothes and had the same hobbies and celebrity idols as my white friends. If I am honest with myself, I can say that I was more attracted to white people and that I used to think that Asian people were less pretty. I thought I was less pretty.”

This so accurately describes my own high school experience that I could have sworn you were writing about me.

“I used to be more comfortable in a room full of white people than a room full of POC. While I can still pass in an all-white crowd, I notice now if I’m the only POC. ”

I’m still in an in-between space with this. I’ve tried explaining this dynamic to people but they just mostly seem weirded out. Thank you so much for validating this.

It’s hard for people to “get” an experience that they haven’t lived themselves. Sorry that people don’t seem to get it!

It’s def valid. I’ve talked to other POC who grew up in very homogenous places — including people who are not adoptees and people who are of other races and ethnicities — and they seem to share this innate ability to code the “right way” in predominantly white spaces. They also seem to share the same guilt around having the ability to pass in white spaces and the same sense that, even if they can “fit in” OK, there are little microagressions that remind them that they are different.

This was fantastic. I could say a hundred things in reaction. Instead I’ll share my experience- I am a half-hispanic queer trans person. I pass as white because my mom is white, and I was raised in a 95% white village suburb. I was treated a bit differently, but I never saw it as racism, but for being different and weird growing up. I rarely embraced my hispanic roots because they weren’t embraced by my first-generation father or my Columbian immigrant grandmother. It wasn’t until I was OUT of college meeting community activists who were proudly Chicana that I realized I was treated as being hispanic based on my last name. That when I apply to jobs they expect stereotypes that have little to do with my actual appearance or behaviors. I don’t know Spanish though I studied in high school. My best friends in high school called me Chi Chi Gomez the housemaid! Or Speedy Gonzalez. Um… racism! Duh! But it didn’t take me until I was 30 to know that.

You’re amazing and this was amazing and thank you for writing it!

Thanks for sharing your experience! I feel your “Duh!” moment. It’s such an obvious realization once you realize it, but it also took me a long time. I consider myself a pretty self-aware person, too! It’s like, Yeah, just because I ignored the ways in which I was marginalized and have been able to get through life in denial in the name of self-preservation does not mean that marginalization isn’t happening.

Loved this piece – thank you so much for sharing!

WHOA. WHAT. A. PIECE.

I’m not an adoptee but I get the part where you’re like ‘I ID as American’ because I grew up in the US of A but then you’re like ‘yeah I’m kinda asian?’ Looking back, I think that when my parents made an effort for me to know about the Filipino culture, I sort of shunned it away. In my mind it was like ‘I don’t need to know these things.’ But then the most amazing thing(at the time, I really thought the world was ending) happened. I HAD to go to school in the Philippines for HS and college. THAT really threw me into the culture and it threw me in fast. And then I remember like the first 2-3 years I was so uncomfortable around my classmates because they made fun of my American accent, not being able to read our language, and everyone was Filipino when I was SOOOOO used to seeing more white people. I don’t think I’ve ever felt so disconnected in a way with my own race.

PS

Kaelyn is a keeper! (contributor-wise)

Your HS experience sounds so intense. I can’t imagine! People assume racial identity is static, a fact about you that is constant. But yeah, skin and lips and eyes and cheekbones and hair does not a racial identity make. The colonized version of U.S. history doesn’t help.

I am still in the process of connecting with the culture behind my ethnicity and I still feel very much like a tourist.

Do you feel like you came out on the other end of HS with a deeper connection to being Filipino?

*colonialized Ha. Well, I guess colonized is accurate, too.

I’m a Korean adoptee who grew up in a German/Irish/English/etc. household and I have two older brothers, both biological to my white parents. My mom told me from a young age that I was adopted (I would repeat it, like a parrot for a long time, not really understanding it) so I always knew I was different. Who knows the motivation behind her telling me that repeatedly, all I know is that I spent a long time in front of the mirror wishing I had blonde hair and blue eyes like one of my big brothers.

Growing up was hard. I know growing up is hard for most kids, my teen angst and struggles are not singular. My family is white, my friends were white, and I felt white. And when I would be out with my family I would always be stared at, singled out, told by the stares from others that I didn’t belong with my family. We would be at home later and I would cry and tell my mother and she would tell me that people stared because I’m beautiful. But I didn’t have blonde hair and blue eyes, how could I be beautiful?

Mostly I struggled, and still struggle, with the feeling of being alone. I find that even when surrounded by people I’m alone. Even when I’m with my girlfriend, laying next to her, I’m alone. I have no idea if other adoptees feel the same, but I know I can’t be alone in these feelings.

Thank you for your article. I’ve spent 31 years whitewashing myself, for my comfort and the laughter from those around me. Maybe it’s time that I learn to accept this part of me, too.

Thanks for sharing your experience. My parents also told us we were adopted frequently. In my case, though, I truly think they were helping us understand it and trying to destigmatize it, knowing that people might point it out or even make fun of us as we got older. They wanted me to love myself. As you say, the teen years make everyone hate themselves. For me, who knows how much of that was regular teen stuff, how much was race stuff, how much was queer stuff. I don’t know.

I have often felt alone, though, as you describe. I have the kind of personality and do the kind of work where I am often surrounded by people. I have a mostly extroverted personality. However, I rarely let people actually be close to me. I realized recently, while learning more about KAD stuff, that this is common among Korean adoptees in the U.S.

If you are interested (and by all means, feel free to not be interested in this unsolicited book suggestion), there are some great books out now w/ first person stories of KADs. This is the one that I stumbled upon that helped me make sense of a lot of the stuff I experienced growing up: Once They Hear My Name: Korean Adoptees and Their Journeys Toward Identity. I am also looking forward to reading Adopted Territory: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Politics of Belonging sometime soon.

Much love to you, friend!

Thank you for your comment! I’ve only recently come to terms with my sexuality, and I just attributed my loneliness to this. What you’ve written has caused a light bulb to switch on so I can see that my ethnicity absolutely caused/causes loneliness in my life. More so as a youth/teen than as an adult, but it definitely is still a factor today.

The loneliness can definitely be a “both and” kind of thing, right? Certainly being queer can make someone feel “on the outside.” It seems to be a common thing for queer people and for transnational adoptees.

So much of this resonated with me as a 1st gen Korean-American. My mother clung to her cultural identity but my father shunned his and insisted that if I was ever asked about my ethnicity, I should only reply with “I am American.” I was raised in a very white town and had the economic privilege of being solidly middle class/upper middle class, so my peers were 95% white and I felt most comfortable around white people. At the same time, these white people never ever let me forget I was NOT white. So many comments about slanty eyes and flat faces from the age of five. The weird dichotomy of being taught by immigrant parents to assimilate as much as possible into the dominant local hierarchy (white white white) but daily being oppressed by that very hierarchy was a mind trip growing up. THANK YOU for this article.

Transnational adoptees and 1st gen folks have an awful lot in common. Thanks for sharing your experience!

In one of my less great moments, I once told a school friend who I rode the bus with me that she had Nazi eyes. Super not OK and also I don’t even know what that means. But she used to make fun of my eyes and I got tired of it and she was German. I was probably 6 at the time.

Loving your voice on Autostraddle, both as a writer and a participant in comment discussions!

Aww, gosh. Thanks! I’m so happy to be here!

I love this! As a Korean-American adoptee, I had no idea other Korean adoptees felt the same way. Reading this was kind of spooky. It’s like you were in my head! Nicely done, and thank you for writing it. I’ve shared it with a few people to both better explain how I feel/felt and to gauge reaction from other Korean adoptees.

Thanks for your comment! It’s awesome to connect with other queer Korean adoptees through the comments here. I have only met one other queer Korean person IRL. Well, not counting Margaret Cho but I don’t really know her in IRL. I just went to her show and geeked out. Anywho, I know we’re out there but I rarely connect with other folks like me. It’s nice to have these convos with ya’ll! We should have a meet up at the next A-camp. I’ll bring the scallion pancakes.

So much yes to all of this. The ways in which we attach ourselves to bits of our identity when we don’t fit cleanly into boxes are so strange.

I also know this story is hard to write. Especially as people who spend our time trying to be anti-racist, feminist, etc. It can be tough to admit that we ever truly internalized so much, even as we simultaneously work against it.

Also, your baby pics are just the most.

This is fantastic. Thanks for sharing!

I love this piece. As I was reading, I found that so many aspects of your experiences resonated with me as an immigrant in a country that I have become accustomed to. Having lived here for over 13 years, everything becomes so normal that I sometimes forget my own identity. I guess, you just don’t realize how ‘different’ you are until someone points it out to you. My appearance always speak for me before anything else. People would typically identify me as an Asian and assume that I reflect all the other “Asian” mannerism. Yet, I can probably say that I wouldn’t be any different had I been born here.

Finding my own identity is a life’s journey. And for me, I have no doubt that it will constantly change as I encounter different people and experiences in life. Maybe someday, I may find that I am only comfortable as ‘me’ a person who is identity-free.

Anyway, thank you for sharing! Your story definitely speaks out for many of us who share similar experiences as you!

All I can say is thank you for saying everything I have always wanted to say, but in a more eloquent and clever way. I experienced a lot of this as adoptee who lived in Korea for a few years and trying to fit in as a Korean in America and an “American” in Korea. Brilliant piece and I hope non-adoptees take the time to read this as well.

Thanks, Caitlin! <3