Thirsty Classics is a 9-week miniseries celebrating lesbian cinema from before 1980. We often talk about these films like homework or mere stepping stones, but Drew is here to share how they can be fun… if you’re horny enough. This week: Chantal Akerman’s Je Tu Il Elle, starring Akerman and Claire Wauthion.

Chantal Akerman was 24 when she directed her first narrative feature, Je Tu Il Elle. She was 25 when she directed Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, one of the most celebrated (and influential) films of all time. And she was 65 when she committed suicide.

Akerman struggled with depression her entire life and it was often reflected in her work. Known for contemplative cinema with long takes and minimal action, it sometimes feels like Akerman created a cinematic form to reflect her mental illness. But she also directed a musical, a romantic comedy, and documentaries on subjects such as the collapse of the Soviet Union and immigration across the Mexican-American border. It’s tempting to make generalizations, but Akerman was a complicated person and a complicated artist and her work deserves complicated discussion.

Akerman often balked at being reduced to feminism, or Judaism, or lesbianism. She was notorious for responding harshly to interview questions and she rejected the way film culture discussed experimental cinema. When a fan commented on FaceBook that her work influenced his screenplay, she responded, “well, I wnt so percentage.” Four minutes later she added, “i am serious.”

This is all to say that I have absolutely no idea if Chantal Akerman would be delighted or horrified that I’ve written about her 1974 film in a way that, if successful, will lead you to 1) seek out the mental healthcare that you need, and 2) masturbate.

The writing process

Je Tu Il Elle begins with a woman sitting in a chair with her back to the camera. This woman is credited as Julie, but we never hear her name. She is played by Chantal Akerman. Her narration begins: “The first day I painted the furniture blue.”

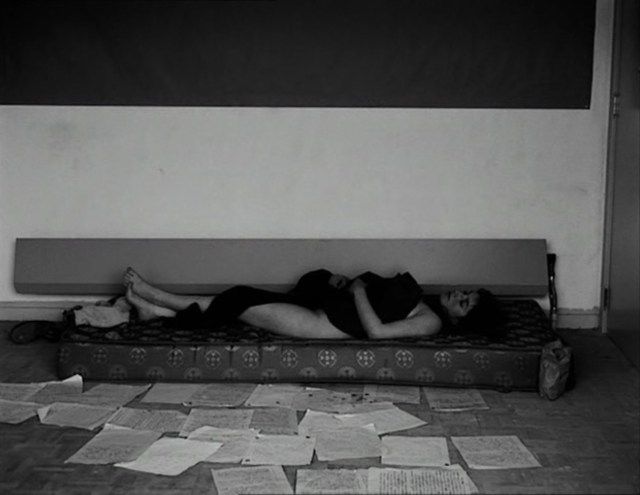

The first 31 minutes of the movie take place in this room. Julie has recently moved in and is finding it difficult to go out. She paints and repaints the furniture. Then she moves the furniture into the hall leaving only her mattress. Then she pushes her mattress against the window so she can sit on the floor in the dark.

She tells us this in her narration and we see it happen. Sometimes the images are ahead of the voice and sometimes the voice is ahead of the images. Each action is given time to play out. There are minimal cuts. And when the scene does change it happens with a slow fade to black. The tedium of the viewing experience is the tedium of life. Or at least the tedium of life in a depressive state.

Julie wears a loose button down shirt and black pants. Her wavy hair is mid length and greasy. She looks very gay in her appearance and her posture and her gaze when on occasion she looks directly into the camera.

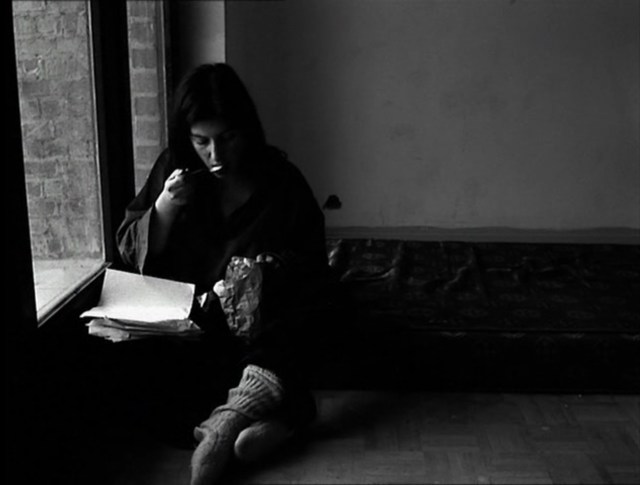

She begins working on a letter. She tells us that it started as a three-page letter, but quickly doubled in length. Her mattress has returned to the floor and she writes perched on top of it. Then she moves to the window where she continues to write while scooping spoonfuls of sugar into her mouth. Everyone has a different depression food and I’m certainly in no position to judge.

She eventually abandons the letter and focuses on the sugar. She scoops faster and faster until the bag rips and she has sugar all over her mouth. She smacks her tongue and returns to the letter. She’s trying to feel something.

She tells us that she keeps writing and rewriting this letter. She lays out all the different pages, far more than six, and then lies down on the mattress defeated. She removes her clothes. It’s something to do.

She begins to spend much of her time naked. Walking around the apartment at night. Draping herself against a wall for extended periods of time. Looking out the window. She never leaves. She can’t. And then it starts to snow. Now she really can’t leave. It’s a good excuse.

But then the snow stops. She looks at her reflection, she tries to smile, she gets undressed, she gets redressed, and, finally, she goes outside.

I’ve definitely done this with peanut butter

The first shot we see outside the studio apartment is a highway. It’s not empty, but it’s not crowded. The cars feel lonely. Julie stands on the side of the road trying to hitchhike. A trucker picks her up.

They go to a restaurant. They eat next to each other without saying a word. This must be her first full meal in weeks.

Back in the car, she mentions in narration that she likes the trucker’s neck and red hair. She says, “I thought I wanted to kiss him.”

(At this point you might be thinking, What’s with this straight road trip? Isn’t this supposed to be gay? To which I say, shove it with your biphobia and be patient!! If there’s one thing Chantal Akerman’s work requires, it’s patience. That includes waiting for the gay shit.)

The road trip continues, still mostly in silence. They drive, they go to bars, and eventually she gives the trucker a handjob.

This opens him up and he becomes real chatty. He shares that he has a wife. He starts complaining about their sex life, blaming their kids, and talking about them like he isn’t half the reason they exist. He ends by saying his now 11-year-old daughter is a “dish” and he’s tempted to rape her. Can’t a queer woman have some empty sex with a trucker without him being a total creep? Guess not!

Alcohol definitely required for this hook up

Julie finally arrives at her destination. She leans into an intercom and says, “It’s me.”

She has come all this way to see an ex. Of course, she has. The letter she was writing and rewriting? Probably, definitely, certainly to this woman. And this woman is happy to see her. She keeps trying to tell Julie she doesn’t want her there but then she smiles and invites her in to eat.

She feeds Julie sandwiches that consist of a slab of butter and globs of Nutella. I guess a meal that’s basically eating sugar out of a bag is better than before when she was literally eating sugar out of a bag.

Halfway through her second sandwich, Julie reaches towards the woman and unclasps the top buttons on her floral dress. The woman shakes her head no, but keeps smiling. The two of them look at each other, eyes dripping with lust.

The woman says Julie has to leave the next day. We cut to them, naked, in bed, fucking.

Patience pays off!

The liner notes on the DVD release, written by a man, state that, yes, the film includes a ten minute, nearly uninterrupted, lesbian sex scene. But, he clarifies, “Akerman severely complicates our voyeuristic impulses through flat, detached compositions.”

He says “our” as if our gazes are at all similar. But I am a woman. I am gay. And, most importantly, I am incredibly horny.

Proof that sometimes it is a good idea to sleep with your ex

The woman is on top of Julie, their legs intertwined. Julie grasps at the woman’s back pulling her in closer, tighter. There aren’t a lot of moves here. Just lust. Greedy, desperate, emotional lust.

They kiss, breasts pressing together, their bodies folding into each other. They roll back and forth, like they’re fighting for control, desperate to consume the other. The woman’s hand slides down Julie’s back emphasizing her shoulders, her hips. Their skin looks so smooth in black and white.

They want to be close to each other, but they can’t possibly be any closer. Julie presses her pussy against the birthmark on the woman’s right thigh. She arches her back again and again pressing as hard as she can. If only there was some way they could be even nearer, more connected, if only there was some way their hunger could be satisfied. They press tighter, they kiss deeper. They try.

The woman starts to kiss down Julie’s body. Julie lifts herself up and kisses the woman’s body. Maybe they’re fighting for control again. Maybe they just need each other so badly they can’t take turns. There are no gaps between them. Julie shakes her hair back and bites the woman’s shoulder.

Anytime one of them pulls away, to readjust, to try something different, the other one pulls them back in, refusing even that one second apart. During one of these moments they flip to the opposite side of the bed. The movie finally cuts.

We’re now looking down at the top of their heads, the classic queer women in bed shot but flipped upside down. Julie and the woman kiss. We’re close enough to see their tongues moving together, to see the woman widen her kiss to the side of Julie’s face, to see Julie do the same. Their mouths stay open. Kissing isn’t enough. They need to feel their tongues all over each other. Julie kisses the woman’s breast. The woman kisses her neck. This isn’t enough either. They return to each other’s mouths. Their hair is tangled in their faces. They get mouthfuls of hair. They don’t mind.

We cut back to a wide shot. The woman opens Julie’s legs. She maintains eye contact with Julie as she lowers her face. Then she lets her hair fall down. She puts her mouth on Julie’s pussy and one hand on her breast. Julie’s hands grab onto her long hair spreading it around her back and then up to her head and then down and up again as she writhes in pleasure. Julie starts to pull the woman up to her, but the woman keeps going. She presses Julie’s legs over her head and begins to kiss her once again. Julie lets her arms fall to the sides in defeat.

She presses her body into the woman’s mouth. She arches her back again and again. The woman holds on, keeping her face between Julie’s legs. It appears as if Julie cums. Quietly, but with an exhale, her legs fall and her body relaxes. The woman lets her arms slide down. She rests her head on Julie’s stomach as it rises and falls quickly with breath. Julie pulls her up and they cuddle hands still moving around each other. They keep kissing.

They’re still kissing when we cut to them asleep. Julie looks sweet in the woman’s arms. The promise of the previous night seems uncertain. Until Julie wakes up, opens the blinds, grabs her clothes, and leaves. The woman remains asleep barely even moving in the light.

A joyous song plays over the credits, but it doesn’t feel joyous.

Seriously, did Chantal Akerman invent this trope??

People should not be defined by their mental illness. And people’s art shouldn’t either. Je Tu Il Elle obviously centers a woman with depression. It does it wonderfully and to deny that would do the work and Akerman a disservice. But can there not be pleasure within? Pleasure in painting your furniture, that small amount of control, pleasure in the first taste of sugar, before it makes you sick, pleasure in crafting a letter, before it feels impossible, pleasure in meeting a stranger, before he reveals his full self, pleasure in fucking your ex, before you have to leave.

Chantal Akerman is one of the greatest film artists to ever live. And she did. She lived. For 65 years, she lived with depression. That’s an achievement regardless of the end. She also shot a ten-minute lesbian sex scene in 1974. That’s an achievement too.

“I will never permit a film of mine to be shown in a gay film festival.” – Chantal Akerman, 1950-2015

I’m sitting here in my cubicle at work wishing I could watch this

My main goal here was to disrupt as many cubicles as possible on a Monday morning.

well here it is, Tuesday, and still disrupted!

You’ve succeeded beyond your wildest dreams. My cheap fabric walls are scorched.

I definitely rewound and rewatched that sex scene (maybe more than once) because a) I couldn’t believe it was happening and b) well you can guess…

“If there’s one thing Chantal Akerman’s work requires, it’s patience.”

I was going to say the same thing! I love this movie so much. It’s hypnotic. Haven’t watched it in years, but still think about it often.

Okaaay, I’ll go masturbate.

“He starts complaining about their sex life, blaming their kids, and talking about them like he isn’t half the reason they exist.”

LIKE KIDS AND WIVES JUST HAPPEN TO YOU AND YOU MADE ZERO CONSCIOUS DECISIONS BEFORE YOU REALIZED YOU ONLY WANTED HANDJOBS FROM HITCHHIKERS!!

Sorry, I work with guys very like red hair trucker, I’ll go get back to the good bit, now!

AHEM.

I LOOOOOOVE YOU, DREW. WILL YOU MARRY ME?

Thank you for bringing these movies to the spotlight. Chantal Akerman is one of the greatest filmmaker in history, the womas was genius. You mentioned 2 of my favorites movies from her, the other one is Les Rendez-vous d’Anna.

That sex scene? I’ve seen and done a lot of things, and that scene is still, hands down, the most erotic thing I’ve seen in my life

Hahaha!

Les Rendez-vous d’Anna is one of my very favorites!! It’s so underrated. I think because it’s the most explicitly queer of Akerman’s work (well, not the most explicit sexually but otherwise…) it often gets ignored by the canon.

I agree about Les Rendez-vous d’Anna.

And I think that there’s some truth on the idea that because this film was released after Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, everybody expected Les Rendez-vous d’Anna to have the same style/thematic as Jeanne Dielman.

Clearly some people don’t have any freaking idea who Chantal Akerman was, because if you think that she would make the same film over and over again you’re dead wrong.

Your writing is always filled with such humor and heart. Thank you dearly. Always look forward to this series

Thank you. :)

Well okay I need to get this movie for science.