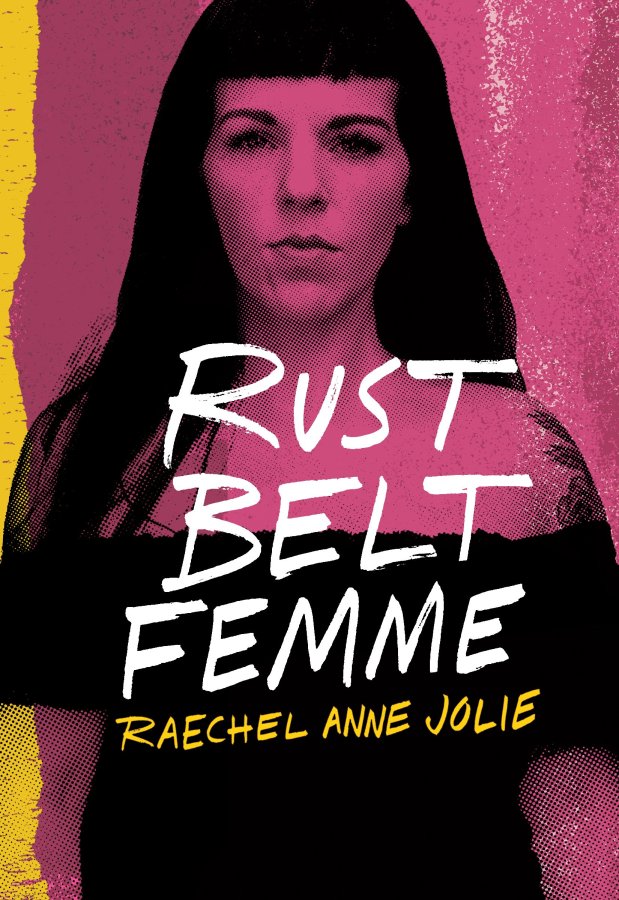

Feature image via Raechel’s Instagram

Raechel Anne Jolie grew up in a rural working-class community in Northeast Ohio at “the very beginning of country Ohio, ten minutes and I was in a suburb, ten more minutes and I was in Cleveland so I was at the very edge of rural Ohio. My earliest memories of life are dirt roads, creeks, yards that went on forever, and the woods.” Jolie’s memoir, Rust Belt Femme, is an exploration of her rural foundation combined with alternative ’90s punk culture shaped her as she is today — “a queer femme with PTSD and a deep love of the Midwest.”

Jolie’s father was a race car driver and was hit by a drunk driver when she was four. That was the catalyst for Jolie’s exposure to queerness — one of the guys on the race car crew moved in with Jolie’s mother. Chris was gay and deeply closeted, but Jolie’s mother knew, and Jolie found out herself around age 12. “I had this clear idea of someone who I was very close to, who I loved, who helped take care of me, who my mom loved and had no judgement about, but it was the ’90s. And he was very afraid of what the people he worked with would think. I had this very early understanding that queer people exist in these communities and that people are going to respond to it differently the way they would in any other community.”

Jolie’s queerness is heavily shaped by the rural culture she grew up in — specifically in her gender identity. “I grew up in what would be considered, and I’ve lovingly reclaimed, a ‘white trash’ neighborhood that had all the markers of ‘white trash living.’ My dad was a race car driver, men without shirts on, drinking beer, covered in car grease, women in short shorts, everyone smoking and swearing.” As Jolie has aged, she’s developed a fondness for the culture she grew up in, especially as she relocated to multiple urban areas for higher education. “I’ve come to embrace that ‘lack of decorum’ that I grew up in.” Her embracing of the “white trash” aesthetic “already feels very queer because it’s so non-normative. “It’s already not fitting inside the boxes of what’s ‘appropriate.’ Which is what queers have been doing forever.”

With the publication of JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy in 2016, and the election of Donald Trump, major coastal metro media started becoming more interested in what was happening outside of their horizon line. The downside is we’ll have to sit through a movie of Hillbilly Elegy, but the positive is the attention being paid to the great work coming out of the “flyover country.” Memoirs like Jolie’s exploring what it means to be working class and how that creates and facilitates a queer identity, and collections of queer stories like Samantha Allen’s Real Queer America: LGBT Stories from Red States, and Rachel Garringer’s Country Queers project catalog queer history in areas outside of New York and San Francisco. The art and queer history that has always been present is being unearthed on the national stage.

“By late high school I started meeting queer people my age, but the year that I graduated, 2003, no one in the history of my high school had ever been out.” The process of securing femininity was an arduous one. “It wasn’t awful because I didn’t want [femininity], it was awful because I couldn’t find the right kind. And when I found femme, and not every femme has a feminine gender performance, obviously, but for me, femininity is deeply connected to class. And my working class town was deeply shaped by being a rural working class town. Working class aesthetic looks different in rural areas than urban areas. When you’re poor, it can show up differently. Femme relates to the women I grew up with, my femme ancestors, and my longing to express femininity and perform femininity.”

She left for Chicago for her undergraduate “with lots of debt trailing behind me” and came out about her bisexuality in college. “I grew up around these strong, complex women, who wore short shorts, lots of makeup, and had tattoos, and that stereotype was real, and that was certainly what I was being shaped by. When I heard the word femme and met my first butch and everything clicked into place. Thankfully, I learned the history of femme and butch working class culture, which dates back to the working class gay bars in the ’40s and ’50s, full of queer working class women. So I learned the working class roots of gay bars, and trashy bar culture was something I grew up with. Those things clicked in place for me so quickly and were so affirming.”

Jolie went on to get a PhD in Communication Studies with a minor in Gender and Sexuality. “I went on to be an academic, and it’s been interesting to be in different cities.” Jolie got her undergraduate degree in Chicago, PhD in Minneapolis, and then worked for a college in Boston for five years. “Queerness,” she says, “is a bit sexy in academia. But my partner is trans and uses he/him pronouns and passes and there’s never not the mental gymnastics that every queer person does, even in the ‘liberal university’ that right wing people think exist, it’s still so much mental energy to figure out how to talk about my partner with particular people.”

Being queer is a lot of work wherever you live, and while there is a clear coming out narrative, there isn’t a good “living out” narrative. There’s often a lot of well-meaning bigotry and invasive questions lobbed at queers, especially anyone deviating from expected gender performance.

“I think about the code-switching that has to happen, and it’s less about coming back to my hometown and thinking about it, I have to code-switch no matter where I am.”

The working class escape narrative mirrors the metronormative queer one. The aspiration is to get into college and live in a city, but that can alienate you from your roots, and create a bit of an identity crisis. “For a while I was writing things for academic journals that very few people in my family could understand. Now, with this book coming out, I’m doing more popular writing and that’s much more accessible. I’ve done so much writing that is analyzing my community from home, and I don’t ever want to feel like that gross anthropologist that only studies my past through an academic lens. I don’t want to exotify or exploit the community I came from.”

Jolie has been careful to be honest in her book and loves being able to share her love of the Midwest. “I’m just so excited to think that more stories like this will be available in the world.”

Rust Belt Femme is available from BELT Press where books are sold on March 10th. Preorder it here.

The tarot zine The Prison Arcana, written by c.l. Young, an incarcerated gay black man in Kentucky, edited by Jolie, and illustrated by Jamie Diaz is available here and all proceeds go to the author and illustrator. To participate in the Black & Pink penpal program, click here. Follow Raechel on Instagram and Twitter for upcoming book tour dates and more.

I feel like this book has been on my radar for an AGE, and I’m so glad it’s finally here. Thanks for sharing this wonderful interview!

i loved this book so much, and i’ve admired raechel and her work for such a long time. thank you for this interview. <3

So glad this work is being highlighted here! So important! Thank you!