Parts 1, 2 and 3 of this series are not required but very enjoyable.

History, people say, has a habit of repeating itself. While that largely means we live at the mercy of the cycle of bad decisions made by a privileged few, it has one side benefit of providing a seemingly endless stream of queer women who were thoroughly besotted with their canine pets.

And so we find ourselves back for a barely conceivable fourth installment looking at the big dogs, little dogs and doggy dogs of yet more lesbian and bisexual women of history who were obsessed with them!

Margaret Wise Brown

Author of everyone’s fave secretly queer bedtime story, Goodnight Moon, Margaret Wise Brown was born in Brooklyn, New York City in 1910.

She spent her early years in a house overlooking the East River until, at her mother’s insistence, the family moved out to Long Island, so the kids could grow up in more natural surroundings. Margaret felt instantly at home in the outdoors, unleashing her adventurous spirit and wild curiosity. Importantly, the space also afforded the family a large house with ample room for many pets, including a squirrel, guinea pig and rabbits. Their family dog was a collie named Bruce, after the canine hero of the adventure dog stories by Albert Payson Terhune beloved by the Brown children. When she wasn’t roaming the countryside, Margaret was a voracious reader and story-teller, frequently adapting common tales with wicked twists to scare her younger sister, Roberta.

Margaret with Roberta, Bruce and assorted pets, courtesy Westerly Public Library

This love of books did not translate to academic success; Margaret spent far more time keeping up with her many sporting and social pursuits, first at boarding schools in Massachusetts and Switzerland, then as an undergraduate at Hollins University in Virginia. Despite students being banned from keeping pets at her Hollins dorm, Margaret decided she must have a canine companion. So she engineered a plan to buy a dog in town, then house it with one of the college staff to get around the rules.

Inspired by reading Gertrude Stein at college, Margaret harboured an overwhelming desire to be a writer, though she received less than encouraging feedback from her tutors for her creative writing. More pressingly, this didn’t fit the more practical career expectations of her father, who threatened to cut her allowance off if she didn’t get a proper job, or direct her education towards one. So, in 1935 Margaret signed up to teacher training at the experimental Bank Street School in New York. She was immediately tapped up by the head of the school to work on editing textbooks using their trademark “Here and Now” style, which focused on children’s experiences in the real world, rather than the fantasies and fairy tales that were common at the time. Margaret took to the style with gusto, and soon jumped from editing textbooks to writing them, and then story books of her own imagining, in a prolific career that saw her pen over 100 books over fourteen years. Aside from the sheer quantity of her output, Margaret was revolutionary in pushing new styles and formats that are commonplace now, including what was considered the first board-backed children’s book.

Where she had struggled to put together compelling adult fiction, she found no problem putting herself in a child’s place to conjure up stories that would appeal directly to them. In a guide book she wrote later in her career, Creative Writing for Very Young Children, she would link this ability with her animal kinship: “Children are keen as wild animals and also as timorous.” Despite her success, Margaret’s grasp on financial responsibility never really matured, spending whole pay-cheques on flowers, maintaining her lavish social lifestyle and buying up properties, then wondering how she couldn’t afford to pay rent.

While working at Bank Street, Margaret acquired her dog Smoke, an irascible Kerry Blue terrier that she took everywhere with her. At group editorial meetings, Smoke would curl and doze through readings, and when Margaret found things dull, a gentle toe poke to Smoke’s ribs would elicit a mournful howl to echo his mistress’s feelings. She was commonly seen flitting from publisher to publisher with Smoke under one arm, and a sheaf of manuscripts under the other.

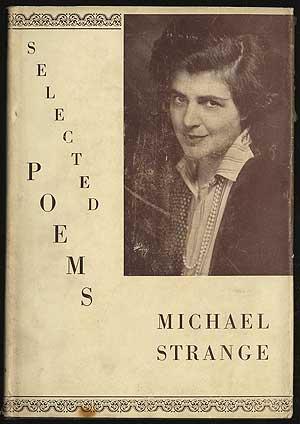

Margaret still spent a lot of time away from the city, enjoying country society from New England to Virginia and indulging in her passion for hunting with beagles. It was during a sojourn to the coast in the summer of 1940 that Margaret met the poet and actress Michael Strange, while they were both visiting a mutual ex, Bill Gaston. If that sentence didn’t provide enough foreshadowing, let me clarify that this gay-sounding meeting kicked off a decade-long tempestuous affair between the two women. Michael was known for her affair and marriage with famed actor John Barrymore (and the erotic poetry she wrote about it), which put her firmly among New York’s artistic elite. Margaret was dazzled by the confidence and sophistication of Michael, who was twenty years her senior. They moved in together in 1943, intent on creating the ideal artistic life, which slowly crumbled thanks to professional and personal jealousy, and the conflict between Margaret’s impulsive flightiness and Michael being a general bitchy drama queen. After a protracted illness, Michael died from leukemia in 1950, which devastated Margaret but ultimately freed her to continue with her life.

One good thing that came out of their relationship was Michael offering to get Margaret a new Kerry Blue after Smoke’s passing. At the kennels Margaret fell in love with the unruliest pupper of the bunch, which Michael tried and failed to protest against. Thus Margaret acquired Crispin’s Crispian (named after some dude in Henry IV)), who became even more infamous than his predecessor, thanks to a predilection for attacking trouser legs, upholstery and literally any other animal he encountered.

Margaret and Crispian

Crispian’s fame was cemented when Margaret inevitably made him the protagonist of his own book: Mister Dog: The Dog Who Belonged to Himself. The story sees Crispian living independently in his own house (modeled after Margaret’s own writing shed, Cobble Court), and his self-sufficiency so impresses a small boy that he chooses to join him in this lifestyle. I am sure this is meant to be making some kind of statement about kids learning independence but also seems a bit gay.

Crispian was just one of many dog and animal stars in Margaret’s phenomenal output. Other anthropomorphic canine characters include Muffin in The Noisy Book, who is temporarily blinded and thus begins to appreciate the sounds of the world. The illustrations for Muffin were based on Smoke’s pup Finnegan who, while modeling, peed on several of the drawings intended for the book. Further doggy pursuits are recorded in The Sailor Dog and Big Dog Little Dog.

To Margaret’s great dismay, the New York Public Library never stocked any of her books in her lifetime, but nevertheless she was loved across the globe. She began a French book tour in 1952, a precursor to a round the world trip she was planning with her new fiancé, a Rockefeller heir nicknamed Pebble. Of course, Margaret took Crispian along with her, despite the reservations of all her friends who knew what a cantankerous creature he was. Despite Margaret training Crispian to understand basic commands in French on the boat over, the wily pooch immediately got himself embroiled in a fight with a local dog, which inspired the following masterpiece:

The Crispian Blues

Bitten on the bottom

In my first fight in France

Why did I not

Wear a pair of pants?

Zut

Et crott

Zis

Ees

Not cricket.

Her trip was cut very short when she landed in hospital with a burst appendix. Although she survived the routine surgery, she developed an embolism while recovering and died. Without children of her own, Margaret’s legacy was split up in an unusual but highly sensible way, with half of her royalties going to whoever took care of Crispian. However, the only person that had read her will to know this was her manager Walter Varney, who immediately tried to wrangle ownership of Crispian to claim the inheritance for himself. This was quickly disputed by Margaret’s sister and literary executor Roberta, who eventually wrangled back control, but such was the nightmare of working with Margaret’s various publishers that over 70 manuscripts remained locked up in a trunk and unpublished until the 1990s.

In the 1970s, the New York Public Library finally decided they would start carrying Goodnight Moon, after two decades dismissing its modernist style, and even the need for a “go to sleep” kind of book. Its popularity rose from the thousands sold every year when it was published, to almost a million annually today, ensuring the legacy of Margaret Wise Brown is read around the world every night.

“I like dogs

Big dogs

Little dogs

Fat dogs

Doggy dogs

Old dogs

Puppy dogs

I like dogs

A dog that is barking over the hill

A dog that is dreaming very still

A dog that is running wherever he will

I like dogs.”

― Margaret Wise Brown, The Friendly Book

Billie Holiday

Iconic jazz singer Billie Holiday was born in Philadelphia in 1915, and raised in Baltimore. She suffered an unstable and abusive childhood, establishing a pattern that would define her personal life. Passed between relatives while her mother worked away and her father was nowhere to be seen, Holiday spent her early years surviving life and sexual assault in one of the city’s most impoverished neighbourhoods.

Billie moved to New York aged 14, where she was trafficked into the sex trade and later imprisoned for it. After release, Billie began singing in nightclubs, developing her trademark vocal style and phrasing, and started to gain some independence. However, the brutal realities of life as an entertainer and woman of colour in the segregation era saw Billie frequently at the mercy of unscrupulous men profiteering off her talent and burgeoning drink and drug addiction.

Thank goodness for dogs! In the absence of decent humans in her life, Billie was supported and comforted by a series of pet pooches throughout her career. As fellow singer Lena Horne recalled about Billie: “her animals were her only trusted friends” and an evergreen topic of conversation.

Among her menagerie were:

– Rajah Ravoy, named after a local magician, who she gave away to her mother

– Gypsy, a great Dane

– a wire-haired terrier named Bessie Mae Moocho

– a Standard Poodle who Billie, sobbing, wrapped in her finest mink coat for cremation when it died

– several Chihuahuas, including Moochy, Chiquita and Pepe, the latter whom she hand-fed with baby bottles and carried everywhere around town

It was Mister, an enormous Boxer dog, that became Billie’s closest companion, loyally sitting stage-side whenever she performed and generally happy so long as he could hear his mistress’s voice. In return, Billie knitted him sweaters, fed him steak and bought him his own mink coat (obviously there was a lot of mink to go around back then).

Billie’s drug use put her frequently at odds with law enforcement, not least because of the relentless campaign by Harry Anslinger, head of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics, whose personal vendetta against jazz culture, Black people in general and Billie in particular almost drove her to suicide. In 1947, police raided Billie’s apartment and busted her for possession, leading to a year in prison. After release, Mister (who Billie thought would have forgotten her), bounded up to her with such ferocity in the street that a bystander thought he was attacking her.

by William P Gottlieb

Prior to her incarceration, Billie’s commercial success had been at a high, with hit singles, record deals and a starring Hollywood film role. With her conviction somewhat restricting where she could perform, she still managed to play several sellout concerts in the late 40s, but the deterioration of her health from constant drink and drug abuse made performing increasingly difficult, and left her even more vulnerable to those out to exploit her. The shadows of Billie’s chaotic life managed to fall over even her most stalwart companion. Contemporaries recounted how in their drug-fuelled benders Billie and her friends hit and abused Mister, even shooting him up with heroin. Eventually, Billie gave Mister away to her pianist, Bobbie Tucker.

Holiday was arrested on drugs charges again in a Hollywood nightclub in 1948, San Francisco in 1949, and Philadelphia in 1956. When hauled off to City Hall for the latter charge, she insisted on bringing Pepe her Chihuahua with her, and he stayed the night in jail.

Billie managed to tell much of her own version of events in her 1956 autobiography Lady Sings the Blues, although notable omissions include her affairs with women, including Tallulah Bankhead, allegedly after Bankhead saw a draft manuscript mentioning their relationship and threatened to sue.

Holiday’s health worsened and by early 1959 she was seriously ill with cirrhosis of the liver, dying in July of that year. It’s said that in her hospital possessions were found a shopping list containing three items: cigarettes, gin and dog food.

Rosa Bonheur

I debated a long time about whether to include the 19th century artist Rosa Bonheur in this series. Sure, Rosa loved dogs, but she loved all animals, with no particular evidence she was more obsessed with dogs than others. I fretted: what if the pan-animal-loving community accused me of erasure? Conversely, what if the dog-lovers accused me of diluting their canine-exclusive identity?

Eventually I realised that loving a lion does not mean you love dogs any less, which I think is a valuable lesson for us all to learn. So, with gay abandon, let us celebrate the life and loves of France’s greatest cross-dressing animal painter, Rosa Bonheur!

Rosa was born into a family of artists in Bordeaux, on March 16th 1822. Naturally, she followed the family passion and was drawing from before she could read, or even talk, devoting hours to sketching her favourite subject: animals. Her obsession was so overwhelming that she eschewed learning to read and write in favour of drawing, until her mum ingeniously persuaded her to learn the alphabet by assigning her animal pictographs to draw, representing each letter.

Despite her quite obvious artistic desire and talent her dad was reticent to give her proper training for reasons that are not clear, so let us just blame the patriarchy. The family moved to Paris, and when Rosa’s insistence on becoming an artist wouldn’t abate (and she kept getting kicked out of school and apprenticeships for being unruly) her father finally relented. He began to bring back animals to the family studio for her to study, and she progressed to making field trips to the outskirts of Paris to paint livestock in their natural habitat.

It was while in Paris that Rosa began wearing trousers and other stereotypically “masculine” attire, largely for practical purposes. As a regular visitor to abattoirs as research for intricate anatomical studies, she discovered it was a real drag in skirts, but because it had been outlawed for women to wear trousers since 1800 (and not officially repealed until 2013!!), she had to obtain and constantly renew a permit to do so.

She had a house on Rue d’Assas where she somehow kept: “One horse, one he-goat, one otter, seven lapwings, two hoopoes, one monkey, one sheep, one donkey, two dogs, and my neighbour Mme. Foucault, mother of the famous physicist, who used to get on the wall to watch me mounting my mare, Margot” (not sure how Mme. Foucault feels about semi-inclusion in this list). As well as the animals, Rosa moved in her girlfriend, Nathalie Micas. Rosa and Nathalie had been at school together in Paris and matched each other with their passions for animals, with Nathalie frequently taking on the role of nurse to their unwieldy menagerie, and having a special talent for taming the various wild beasties they acquired. Nathalie’s mum also moved in with them, but as far as I can tell, she had no concern about her daughter’s lesbian affair. It is likely Mme. Micas was too distracted by the otter’s penchant for escaping its water tank and leaping into her bed. Even when Rosa attempted to give away animals, they had a habit of returning, as happened with a dog they gifted to a friend who immediately left and trotted the thirty mile trip back.

Rosa’s animal obsessions paid off, and after some early successes with huge pastoral scenes such as Ploughing in the Nivernais she was able to set up a much larger studio just outside Paris in Château de By, in 1859. She immediately set about moving in an even more outrageous array of pets, including but not limited to:

– stables filled with all sorts of horses, ponies and cattle

– dogs roaming all over the place, including collies, enormous St Bernards’, hunting hounds, dachshunds and terriers

– stags, wild sheep and gazelles

– a parrot called Green Cocotte who could swear in Spanish

– a monkey called Ratata

– a pair of lions named Nero and Fathma.

Naturally, many of these animals were the subjects of the many hundreds of artworks she produced over her lengthy career, including dozens of dog portraits and studies.

Of all the dog obsessives I have studied, Rosa is perhaps the first that has made me wonder if she was actually an addict, frequently documenting her inability to go anywhere without acquiring a new pet. Witness this time she went on a trip in the Alps in 1850 and got a giant mountain dog:

“My dog is getting enormous. I don’t know how I shall manage to convey him from here, for he will be as big as a donkey, Dear me! What an unfortunate hobby mine is! What would you say if I were to confess what efforts I have made to resist the desire to bring back a sheep and a goat? I really can’t help it.”

Among her named dogs, we have: Belotte, a large yellow bassett, Pastour, Ulm (a big Danish dog), Niniche (a Corsican mouflon), a Scottish terrier called Wasp, a beagle called Ramoneau, long-haired Daisy and Charlie, who Rosa trained to do tricks, and her favourite, Gamine, who was glued to Rosa’s side, lording it over the other animals and always the first to scraps at the dinner table.

After almost 40 years together, Nathalie passed away, in 1889. A few years later, the couple’s friend Francis Power Cobb lost her own partner Marie Lloyd, and Francis and Rosa exchanged letters and photos of their loved ones with their faithful dogs, to remind them of their happiest times.

Rosa was not alone for long. An American painter named Anna Klumpke met Rosa on one of her regular trips to Paris, and the two hit it off. Anna had idolised Rosa for years, and even had an official androgynous dress-up Rosa Bonheur Doll. Anna plucked up the courage to ask if she could paint Rosa’s portrait on her next visit, to which Rosa agreed and they promptly fell in love during the process, because all clichés have to start somewhere.

Rosa with Charlie by Anna Klumpke

Anna moved in to the chateau and they lived together until Rosa’s death in 1899. Anna maintained the estate (including all those animals) until her own death in 1942. Rosa, Nathalie and Anna are buried together in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Edith Somerville and Violet Martin

Both daughters of wealthy 19th century Irish gentry, Edith Somerville and Violet Martin met in 1886 in Castletownshend, the small village near Edith’s family residence, Drishane House. I suppose tangentially it was Violet’s family home too, as the pair were second cousins, although they didn’t encounter each other until their mid-twenties so probably it was totally fine that they embarked upon a lifelong artistic and romantic relationship together.

Eldest of eight siblings, Edith was a smart and confident character, with a passion for reading and drawing, and a determination to make her own way in the world. After persuading her parents to let her go abroad to study art, she was able to earn a living as an illustrator and set herself up with a studio on the family estate. With no desire for marriage herself, Edith was devastated when her childhood “best friend” Ethel tied the knot, and was entirely unattached when she met Violet.

Similarly self-motivated, Violet was a self-taught linguist and keen student of the written word, and was trying to get some of her articles published when a family member suggested she seek out Edith to provide illustrations. Their collaboration was an instant success, and the pair clamoured to spend more time together despite familial obligations and financial dependency keeping them apart.

I suppose our respective stars then collided and struck sympathetic sparks. We very soon discovered in one another a comfortable agreement of outlook in matters artistic and literary, and those colliding stars lit for us a fire that has not faded yet.

– Edith Somerville describing casually meeting her cousin Violet.

Violet helped redirect Edith’s passions in a more literary direction. Their first novel together was, ironically, An Irish Cousin, and after positive reaction to the book, their families were somewhat content to let them continue their unusual collaborations. For the first two decades of their partnership, they didn’t live together, but would meet for intense periods of “creativity” and constantly mailed manuscripts and letters to each other. They continued to have success, publishing a number of novels satirising Irish country life, using the joint pseudonym “Martin Ross.”

After the death of Edith’s parents and Violet’s mother, there were few remaining obstacles in the way of the pair moving in together, and they spent the last nine years of their relationship in Drishane house. As the head of the household, Edith assumed responsibility for running the estate, including taking over the hunting hounds, becoming Ireland’s first female Master of the Foxhounds. While they loved the hounds for the hunt, Edith and Violet were also fans of fox terriers, and liked to trot around with them in threes, leashed up like a Russian troika.

Edith and Violet with two of their fave fox terriers, Candy and Sheila

Violet died in 1915, after a long illness following a horseriding accident. However, Edith casually resumed her relationship with Violet on the astral plane, which is as you’d expect for a queer woman. Not only did Edith claim that Violet contacted her from beyond the grave, she also brought with her news of their long-dead pet dogs. For the rest of her life, Edith continued to use the pen-name Martin Ross, as she fully believed she was still writing in conjunction with her deceased lover. Although Edith went on to live for a further three decades, she remained faithful to Violet’s spirit, despite attempted flirtations from fellow suffragist and dog enthusiast, Ethel Smyth.

Edith’s (and ghost-Violet’s) final work was Maria and Some Other Dogs, a selection of previously-penned doggy stories and new musings on the canine condition, collected with illustrations. As well as obligatory tales from a dog’s-eye view, there is a chapter titled “In Praise of Ladies” which although allegedly pertaining to female dogs, could easily be read as a treatise on why females of any species are better.

Yet I am well aware that I am not alone in valuing the Lady, as an intimate, above the Gentleman of the race. I have seldom met an Initiate in the cult of the Dog who did not confess to a preference for the popularly unpopular lady.

Further gems in the collection include the story of a dog whose extreme naughtiness prompted a name change from “Cozy” because that sounded too placid, and a recollection of impressing Thomas Hardy’s widow with accounts of psychic pooches. There’s also mention of private stories about one of their dogs, Puppet, that Violet wrote for Edith, but the latter declared “too esoteric” to print, which is really saying something.

Edith completed the manuscript mere days before her death in October 1949, ensuring a mortal account of her canine obsession was left behind before she rejoined Violet.

Mary Oliver

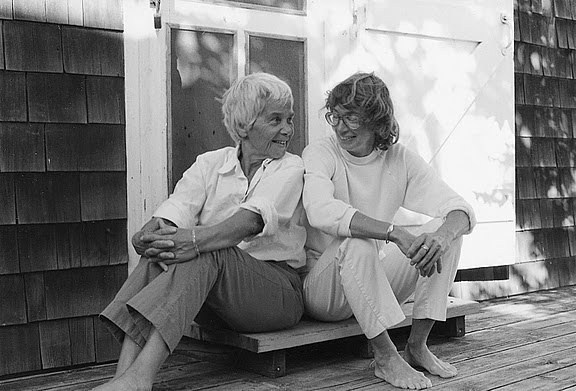

Beloved American poet Mary Oliver sadly became an official lesbian “of history” when

she died in January this year, aged 83. Throughout her long and successful career, Oliver’s work focused on the natural world, walking daily in the forests and beaches of Provincetown, where she lived a private and simple life.

Oliver studied at Ohio State University and Vassar, developing her passion for poetry. It was one such passion for the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay that took her off to Millay’s home in the tiny town of Austerlitz in upstate New York. It was there in the late 1950s that she met (presumably the only other gay in the village) photographer Molly Malone Cook, who would go on to become Mary’s literary agent and partner of more than 40 years.

While she lived with Molly until her death in 2005, Mary also had constant canine companionship throughout her life. References to her beloved dogs are littered throughout her many volumes of poetry and prose, so many that they got their own collection: 2013’s Dog Songs.

Each poem is a gem, capturing the small delights of human-canine interactions, from silent conversations with her dogs watching the moonrise, to cancelling work trips at their mournful howls, to playful interruptions to her tax returns. It is hard to pick out any single one, but here is Mary herself reading Little Dog’s Rhapsody in the Night:

In fitting with her beliefs on nature and wildness, Mary fervently believed that dogs should be free to roam off leash in their surroundings. Otherwise, a dog is a mere “ornament of human life.” But, unleashed: “Dog is one of the messengers of that rich and still magical first world. The dog would remind us of the pleasures of the body with its graceful physicality, and the acuity and rapture of the senses, and the beauty of forest and ocean and rain and our own breath.”

Mary also had the rare foresight to use her essay Dog Talk to list in one place every single dog she had owned (FYI I’d really recommend doing this if you ever plan on becoming a lesbian/bisexual woman of history who is obsessed with your dogs because it will make your chronicler’s life so much easier):

“Baba, Chico, Obediah, Phoebe, Abigail, Emily, Emma, Josie, Pushpa, Chester, Zara, Lucky, Benjamin, Bear, Henry, Atisha, Ollie, Beulah, Gussie, Cody, Angelina, Lightning, Holly, Suki, Buster, Bazougey, Tyler, Milo, Magic, Taffy, Buffy, Thumper, Katie, Petey, Bennie, Edie, Max, Luke, Jessie, Keesha, Jasper, Brick, Briar Rose.”

Through the poems of Dog Songs we get to learn the wild and cantankerous personalities of many of these pooches, and of their owner.

“Be prepared. A dog is adorable and noble.

A dog is a true and loving friend. A dog

is also a hedonist.”

Mary Oliver, The Wicked Smile

Oliver’s essay Winter Hours offers some of the most accessible insights into her feelings about nature (and even a little bit about her relationship with Molly). In it, she describes how after her dog Luke died, she would retrace her steps through the woods where they had walked together, covering the remains of Luke’s pawprints with bark and leaves, so she might preserve them. While a violent rainstorm finally washed those pawprints away, the vitality of life and nature that Mary Oliver captures in her poetry will leave a legacy for generations.

Because of the dog’s joyfulness, our own is increased. It is no small gift. It is not the least reason why we should honor as love the dog of our own life, and the dog down the street, and all the dogs not yet born. What would the world be like without music or rivers or the green and tender grass? What would this world be like without dogs?

Today I learned to wear pants when fighting in France, lest I be bitten upon the bottom. Worth the price of admission!

sally how do you account for the rumors that you in fact do not have a dog

At this point I’d be worried that actually having a dog would hinder my ability to report on them with such scholarly objectivity

sacrificing your own happiness for journalistic integrity, this is why you are truly the best among us

And now I have a new favorite poem!

This is my favorite series ever

Iiiiiiiiiiiii grok it.

I love this series and your dogged persistence, Sally.

I’m always entertained to find the gayest gayness in these, and I’m thinking perhaps having an androgynous doll of your future partner might be the winner. Also a winner for anyone wanting inspiration to make a creepy gay biopic in black and white, I feel.

St. Crispin and his fellow saint brother Crispinian are patron saints of cobblers aka shoe makers, a variety of leather working fields, and some textile works also so it’s kinda funny a menace to upholstery, trousers and likely shoes too was named after them.

Wow guys, wow.

Love this series, but brokenhearted about Mister!