via lindsaytrevor on flickr

When I was a little pre-teen at Dork Middle School For The Mentally Gifted in the early ’90s, anybody who was anybody (which was almost everybody, ’cause there were only 16 girls in my graduating class) read Lurlene McDaniel novels ravenously — stories which confirmed our suspicions that the world was a cruel, sad place, riddled with surprise tragedies and untimely deaths. It was the height of the “grunge” era and despite a relative shortage of “real problems” for most of us at that point, we were a fairly depressive bunch and therefore a ripe audience for McDaniel’s Lifetime-Movie-esque young adult books — according to McDaniel’s website, “everyone loves a good cry, and no one delivers heartwrenching stories like Lurlene McDaniel.” Excellent! We loved crying! We loved romanticized potentially-dying heroines surrounded by soft breezes who spent agonizing hours staring in the mirror wondering how their hair would look after chemo!

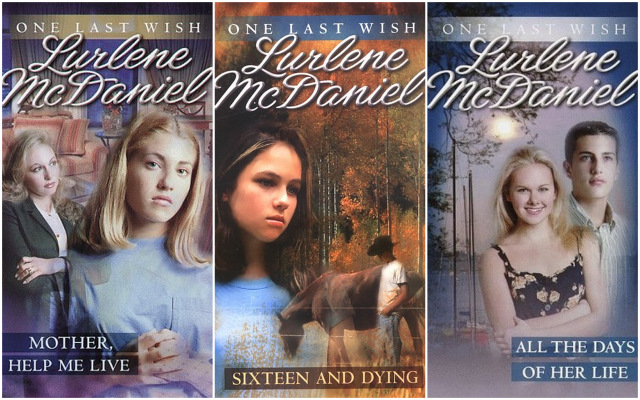

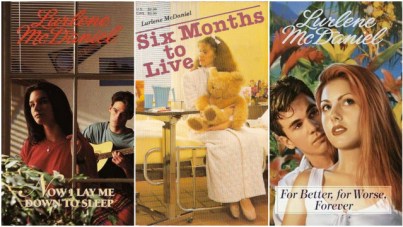

McDaniel hasn’t slowed down since the 80’s and 90’s, she’s now written over 50 books about “kids who face life-threatening illnesses, who sometimes do not survive.” Sample titles include: She Died Too Young, Sixteen and Dying, Please Don’t Let Him Die, The Girl Death Left Behind, Letting Go Of Lisa, When Happily Ever After Ends, and Goodbye Doesn’t Mean Forever. Somebody, usually a healthy happy popular teenager, develops a life-threatening medical condition, and then they either get better or die. Usually they get a boyfriend first. Here’s just a handfull of McDaniel’s book descriptions:

A change is coming, April Lancaster’s fortune cookie reads. Be prepared. But how could she be prepared for the news that she has an inoperable brain tumor?

Sixteen-year-old Kara Fischer has cystic fibrosis and only months to live. But the close-knit bond she develops with Vince, who also has the disease, helps her come to terms with her own illness. Given one last wish, Kara wonders if miracles could really happen.

Jessica McMillian and Jeremy Travino are a perfect couple. But now Jessica has been diagnosed as having kidney failure. She is on dialysis three days a week and is so depressed that she’s not sure she wants to live.

Julie Passanante Elman, a researcher at The University of Missouri-Columbia, recently conducted an examination of the many problematic aspects of Lurlene McDaniel’s world and the results of her deconstruction, “Nothing Feels As Real: Teen Sick-Lit, Sadness and the Condition of Adolescence,” appeared August 2012 issue of The Journal Of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies. A few weeks ago in The Daily Mail, journalist Tanith Carey used Elman’s work and a healthy helping of her own personal opinion to argue that “sick-lit” is a “disturbing phenomenon.” I found Carey’s argument — which posited the theory that “sick lit” began with Alice Sebold‘s The Lovely Bones, of all things (it’s not a young adult book, for starters, it’s also literary fiction), and is best exemplified by, of all things, the recent success of John Green‘s The Fault in Our Stars — baseless and misguided, but was intrigued by the quotes pulled from Elman’s paper. So I tracked it down and read it and that’s why we’re all here today, talking about why Baby Alicia is Dying and how to go about Letting Go Of Lisa.

Elman set out to critique “the ableist and sexist visions of disability and sexuality” in “teen sick-lit,” which she identifies as a sub-genre of the “YA problem novel.” The genre was booming in the 1980s, and that’s the decade of literature Elman has chosen to examine:

While YA problem novels of the 1970s often critiqued racism, sexism and homophobia, teen sick-lit of the following decade largely reaffirmed conservative political and sexual values and reconsolidated traditional heteronormative gender roles that had been “disrupted” by post-1968 identity movements.

My mother refused to buy me any Lurlene McDaniel books or let me borrow them from the library, so I resorted to borrowing them from friends. She just thought they were so unnecessarily morbid, you know? Like who wants to read about that shit? Tanith Carey is similarly disturbed by the inherent “morbidity” of the topic, but that’s where her similarities with my mother’s opposition ends.

See, Carey is offended by Sick Lit’s “sex and swearing” and the “distasteful” decision authors make by “using children with months to live to build dramatic tension.” But after reading Elman’s study and revisiting McDaniel’s work, it’s clear that “morbidity” was perhaps her novels’ least problematic aspect and that addressing chronic illness and death in young adult fiction isn’t inherently problematic at all. Far more disconcerting than her subject matter, and inconspicuously so, was McDaniel’s retro representation of girlhood and race as well as a remarkably ableist vision of disability for a series that claims to advocate for the disabled and ill children it smacks on its white-washed covers. It’s not that she talks about death, it’s how she talks about death.

Because ultimately her stories, while medically accurate, are wildly inaccurate to a frustrating degree regarding just about everything else.

Using McDaniel’s Dawn Rochelle series as a focal point, Elman describes how the novels reinforce damaging cultural ideas about the unattractiveness of ill or disabled bodies — the able-bodied teenagers’ rejection of ill or disabled teenagers is not only accepted, it’s more or less embraced. Often it seems that her characters, once in remission, habitually “trade up” to able-bodied partners. On the topic of Dawn Rochelle’s waning interest in her former boyfriend, Mike, now that Dawn is healthy and Mike still has a prosthetic leg: “Although he may have recovered from cancer, Mike’s disabled body can never be fully rehabilitated into (able) normality, and thus Mike could never represent a viable romantic interest for now-healthy Dawn within the story’s logic,” Elman writes. In the final novel, Dawn’s considering whether to go steady with Brent (who has cancer) and Jake (who does not), and Elman attests that “the series encourages Dawn to adhere to the logic of able-bodiedness by choosing Jake, who fully embodies the ‘good passport’ of the well.” This is in stark contrast to The Fault in Our Stars, in which Hazel’s oxygen tank, Augustus’ prosthetic leg and their friend Issac’s blindness are discussed frankly and the physical manifestations of Hazel’s illness have no affect whatsoever on Augustus’ desire for her.

“Teen sick-lit traffics in the most egregious and patronizing of cultural stereotypes about disability.”

Then there’s the compulsory heterosexuality thing. Like many novels geared towards teenagers, Sick Lit deals exclusively with traditional heterosexual romance. Elman notes that within the “compulsory able-bodiedness” social framework, “heterosexuality and health often seamlessly imply one another, while queerness and disability exist as epitomes of abnormality.” S.Chris Saad, in her study The Portayal of Male and Female Characters With Chronic Illnesses in Children’s Realistic Fiction, 1970-1994, found that 80.8% of the books studied featured chronically ill female main characters and that “when books were considered as a group, a pattern of sexism, racism and heterosexism emerged.”

Elman argues that sick lit was not unaffected by feminism so much as it was molded in direct opposition to the ideal of the women’s movement, demonstrating “an assiduous disavowal of liberal second-wave feminist ideals. McDaniel’s texts encourage and enforce adherence to traditional gender roles because it is part of ‘getting well.'” In the Dawn Rochelle novels, which Elman focuses on in her studies, she recalls the case of Marlee Hodge, Dawn’s cabinmate at cancer camp, a tomboy who is demonized as a troublemaker who terrorizes sick children.” Marlee’s rejection of “able-bodied and feminine standards of beauty” are used as evidence of an “unhealthy attitude” which won’t help her get well. Brent notes that: “Maybe it would help if she fixed herself up a little… she could make a little effort, you know, some makeup, covering her head.” Dawn tries repeatedly and fails to inspire Marlee to conform and don dresses and makeup, but when Marlee finally gives in and accepts a makeup, wig and outfit, she is applauded and, as Elman puts it, her “queer-crip resistiveness is tamed.”

Then there’s the race thing. Lurlene McDaniel’s protagonists are always white and usually Christian. Actually, and this is so obnoxiously racist that it’s almost a parody of itself — the only time people of color get involved is when somebody works with HIV-positive infants abandoned by their drug-addicted mothers or when the white protagonist takes a missionary trip to Uganda. I know! I KNOW.

It is these tired retro ascriptions to romantic tropes, gender-stereotyping and racial stereotyping that make McDaniel’s work so mockable for adults who once enjoyed the books as children. Forever Young Adult runs a series of Slurlene McDaniel Drunken Reviews, replete with a drinking game: “the only way to read these books is by contracting your own illness: liver failure! Because the best way to judge a book is by how many drinks you’ll need to get through it.”

In a Flashback Friday on the website Mamapop last summer, writer Molly recounts her childhood obsession with the series and Dawn Rochelle novels in particular:

Dawn Rochelle was beautiful, brave, and appeared to have a canopy bed. And I bet she kept a diary. And was in Key Club. And could barely sleep or hold down a job for the aura of romance that constantly enveloped her like Pigpen’s dust cloud. What? Oh yes, she also had cancer. And some hard-luck friends who were dropping like flies. But MYGAWD I wanted to be most-of-her in the worst way. I mean, her name was “Dawn Rochelle.” That is so fancy.

In a 2010 article for BUST Magazine, Marni Grossman argued that her adolescent attachment to these books was rooted in what she refers to as Beth March Syndrome (after the Little Women character) — “the desire to be kind and patient and cheerful and then wilt beautifully and die. Or simply come close enough so that everyone finally appreciates you.” It’s a spot-on analysis and perfectly encapsulates why young adults actually wanted to be these sick girls, despite the fact that there is absolutely nothing awesome about leukemia.

All girls are susceptible to Beth March syndrome, because we’re taught that suffering is a woman’s most noble role, and bearing the wrath of a terminal illness lends an innate goodness to the sufferer. In literature, men go to war to become heroes, achieving immortality through great acts, while women earn their place by courageously battling illness before graciously dying. I envied the girls in McDaniel’s books, not in spite of their ailments but because of them. Dying girls get the last laugh. They are loved and cherished, and they are, above all, good—even if they aren’t. Because you can’t really talk trash about a girl on her deathbed.

I’d argue that it’s McDaniel and her imitators specifically who inspire this response, but not all young adult novelists who address these themes. I mean, do McDaniel’s books offer actual comfort to ill children and their friends/families, or are they strictly voyeuristic? Although McDaniel was inspired to tackle these topics after her son was diagnosed with juvenile diabetes, I found that as soon as actual tragedy visited my own life, my interest in reading her fabricated tomes vanished instantly. Lurlene’s tragedies became sanitized, inaccurate and cloying reminders of my own pain rather than what they’d been before: doors into distant romantic places I’d heard about but not yet visited. I mean, The Boxcar Children seems like so much fun until you’re genuinely unable to find affordable housing.

I think I was possibly drawn to these books because I felt like something was wrong with me too but nobody could see it. I think a lot of teenagers feel that way. But if I was sick like Dawn Rochelle then everybody would know, and they’d all be nice to me and bring me cards and flowers, and I would seem prettier after all the doctor stuff because of how horrid I’d looked throughout treatment. So I think Carey has it all wrong when she quotes a child psychologist who hopes “let’s hope publishers do have young people’s interests at heart – and they are not selling books by sensationalising children’s suffering.” It’s not the sensationalizing that’s the problem with Lurlene McDaniel, it’s the romanticizing, and the prehistoric and repressive social conventions she employs to successfully do so, generally at the expense of anything remotely empowering.

Which is why ultimately comparing Sixteen and Dying to The Fault in Our Stars is like comparing Taylor Swift to Ani DiFranco or the new 90210 to My So-Called Life — and lumping books like those books into the same category suggests a prioritization of topic and plot over sentiment and context. Elman points out that Lurlene McDaniel’s bookmark slogans (“nothing feels as real as a Lurlene McDaniel book”) “suggest McDaniel’s books, and others like them, conjure a relationship between ‘realness’ and emotional intensity in which sadness connotes authenticity.” Unfortunately for the longevity of McDaniel’s position in her readers’ hearts, we all learn eventually that the only thing that connotes authenticity is actual authenticity. Whereas the Lurlene McDaniel cannon relies solely on the depressive weight of its plot to drive the story forward, books like The Fault in Our Stars rely on authentic characters, a healthy sense of humor and a dedication to honesty, even when it’s unpretty.

“While the Twilight series and its imitators are clearly fantasy, these books don’t spare any detail of the harsh realities of terminal illness, depression and death,” Tanith Carey writes in a critical sentence that explicitly misses the point in the most illustrative way possible. What we take away from a book is rarely the meat of it — the vampires, the cancer, the AIDS — but the subtext, what’s underneath it all, the messages about what girls should want, what we should be, who deserves love and who can’t have it. Because the truth is that children do, in fact, suffer, and it’s only natural that children are curious about illness and death and they either already are, or soon will be, grappling with it in their own lives. The pain demands to be felt, as it is written in The Fault of Our Stars. And there doesn’t need to be anything sick about that.

It’s like that weird ass song ‘If I die Young’ or still life paintings showing beautiful fruit about to rot.

I remember the Dawn Rochelle series being recommended to me as a preteen because I had a chronic illness (not cancer) but so much of it rang douchey with me it disgusted me.

The covers to a lot of these McDaniels books provide a lot more amusement than the books ever will.

Me, too. I couldn;t even get past the cover illustration.

I ended up reading a lot of Cynthia Voight.

My sister loved these books when we were kids. I read one once and then went back to Stephen King and V.C. Andrews, the two great pillars of middle-school reading in the 90s. You know, because my sister’s books were so warped and depressing.

All I have to say is….

A Walk to Remember by Nicholas Sparks

It was strange because growing up in the suburbs I look at these book covers of white people embracing or some “angelic” looking white girl looking into the distance. I did’t really have access to a lot of authors or stories that revolved around POC protagonists in my middle and high school years but I enjoyed the stories all the same.

What struck me when reading these stories was the fact a lot of these girls would love from afar and suffer into deep depression or would be slowly dying of an illness where the girl’s chastity would not be compromised. If anything she was put on a pedestal because of her ever so care-free nature that is not destructive and her love is the purest of them all. The male would treat her like some delicate flower, love love love.

Soon after I got sick of it and read a lot of fantasy (which would have some of the same narrative for the female characters) and Ann Rice Vampire chronicles. When I read a lot of Japanese manga again I would see the same narrative of the depressive pining girl or the sick girl that inspires the male characters, I couldn’t escape it! It’s interesting “sick lit” and it’s so true about these woman virtue of being ill and living bravely because it keeps a sense of chastity about her, her love is pure because she going to die soon, don’t compromise her chastity!!!

Preach.

I will confess that I had a lot of feels about Mandy Moore’s portrayal of the “sick angelic white girl” in the Walk to Remember film. #shameful

I felt like sick-lit was morbid and unhealthy until I read TFIOS and fell in love with Hazel and Augustus and the whole story. Usually sick-lit stories feel manipulative to me, like they’re trying to glorify illness, which makes me uncomfortable especially as I’m watching my mother live with her cancer and seeing all the messy uncomfortable things she has to deal with every day.The Fault in Our Stars felt to me like a really honest portrayal of living with a terminal illness, which is a really rare thing in a book. To everyone who hasn’t read it yet: go pick it up ASAP, you will love it!

“homosexuality and health often seamlessly imply one another, while queerness and disability exist as epitomes of abnormality.”

I think you meant “heterosexuality” in the beginning of the quote?

I’d never heard of this author or the “sick lit” genre before, but as always Riese manages to make me find a piece on a subject I don’t know and/or don’t care about utterly fascinating.

Also, my god the books’ covers and titles. They’re so bad it’s hard to believe it’s not parody.

I never read these books, but did read a lot of V.C. Andrews. I’m not even sure what genre Andrews would fall under, but her books are perhaps even more screwed up than “sick lit.” I sometimes wonder what was wrong with me (and many of classmates) that we devoured books about families that were dysfunctional to the point of poisoning and murder and all manner of other ridiculous things. And incest. Can’t forget the incest.

I wonder what John Green would have to say about this.

This was fascinating, by the way. Truly.

“What we take away from a book is rarely the meat of it — the vampires, the cancer, the AIDS — but the subtext, what’s underneath it all, the messages about what girls should want, what we should be, who deserves love and who can’t have it.”

Holy SHIT Riese, this is such an excellent breakdown of both the article and the genre. Like you said, there wasn’t a Scholastic book fair in the late 90s that didn’t blow through and leave little piles of Lurlene McDaniel books on young ladies’ desks.

Does anyone remember the one (maybe more?!) that combined cancer, children dying unexpectedly and THE AMISH?! Instead of sex, there was “bundling” and rumspringa! I imagine the research involved was literally Lurlene reading an article about the Amish and muttering, “Hot DAMN this is great stuff!” and sprinting to her computer.

That was like an entire series or trilogy I think. I remember reading more than one Amish book for sure!

I am now so embarrassed that I read all those in middle school.

holy shit! I am so glad I am not the only one who read those! It was the Amish books that got me started on Lurlene McDaniel. I wanted cancer so badly. And I realize how awful that sounds, but it just seemed like everyone would love you and no one would be mean to you if you had an awful disease, and also, you might get to fall in love and stuff….I realize now that I was a lonely child.

But yes, the Amish ones.

I read “The Girl Death Left Behind” as a kid and it serious disturbed me. Lurene McDaniels’ books are NOT, I think, similar to John Green or Alice Sebold. Those authors have written novels in which yes, death and illness and mortality are real. However, McDaniels’ books seem to exist solely for the exploitative factor, for the “can’t look away from the car crash” idea. Personally, I hated the one I read and found the characters very distant and not relatable. Death is real, but sick-lit has little to do with chronic illness/the experience of a person going through that, and more to do with a romanticized fascination of it. Basically, I think they’re shitty books haha.

oops, McDaniel, not McDaniels!

“Telling Christina Goodbye.” One of the first books I read 6th grade year and could not stop reading every single Lurlene book I could get my hands on. That isn’t a cancer one but every other story about young beautiful girls getting cancer and wasting away was my crack. And now I feel so weird about it. I didn’t even know “sick lit” was a thing!

I seemed to miss the boat on all serialized YA chick lit entirely, from these to Babysitters Club to Nancy Drew.

Sitting here right now, reading what you’ve written and knowing how certain YA books heavily impacted the way my 10 year-old pea brain viewed/continues to view life, I find myself wondering if I’d even be alive today had I read Lurlene McDaniel.

Ah! Having been a kid with a whopping case of Beth March Syndrome myself, I vividly remember these (and wrote about them a little myself at one point: http://poorworkethic.blogspot.com/2012/01/on-not-writing-about-madness.html). Tragic blonde after tragic blonde. It seems natural that this genre would have huge interest in cultural-studies circles, but somehow I’d never come across any of this stuff before. Such a very strange but possibly inevitable genre. I think you, and that Marni Grossman article, capture its appeal precisely.

Oh wow, I actually read most of those books when I was 10 or 11, and to be honest I had completely forgotten they even existed until reading this. I think what you said about romanticizing difficulties until you actually experience real hardship is spot-on. As an elementary school kid, I thought it would be so great to break a bone cause then I’d get to have a cast and see how many people signed it (I know!). And I liked reading about death, hospitals, sickness because I felt like adults didn’t talk about such things enough so I had to learn about them on my own.

I hadn’t made the connection till now, but it was right around the time I actually almost lost my leg in a ski accident that Lurlene MacDaniel lost her appeal. Suddenly her books didn’t seem so real anymore. I was more into Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings – full of complex characters I could relate to, who overcame difficulties (or at least tried to) like REAL, fully dimensional people instead of dying in this weird, romanticized way while agonizing about boyfriends and makeup.

I was a sick teen and read these books voraciously. I still have the Dawn Rochelle series in my bookshelf–her story often feels like my own, but in a more melodramatic way that I kind of am strangely drawn to. I may be crazy for it, but there are a fair number of McDaniel books that I actually genuinely enjoy…and several I’ve not read and/or didn’t enjoy nearly as much. I think part of the reason I liked and still like them is that they’re the first books I read that made me feel as though I wasn’t alone in fighting something that could, in a very real way, kill me.

I didn’t have that back then. My family had pretty well abandoned little 15-year-old me to fight on my own, my friends either didn’t know (because I tried so hard to hide it) or just flat didn’t understand. Most young teens don’t have to face their own mortality like that.

I bawled reading The Fault in Our Stars, wishing that I’d had an Augustus (or some female version thereof…maybe a Hazel Grace) who took care of me and gave a damn while I was sick, because I totally didn’t have that. John Green writes in a way that is probably more real than McDaniel does, but both are appealing for their own reasons and both authors definitely did their research on how the medical world actually works.

And, as an aside, the quote cited here of “That’s the thing about pain…it demands to be felt” is going to be my first tattoo, when I can afford it and the doctor says I can, which will probably be at least 5-6 months for the latter and even longer for the former.

I’ve never heard of McDaniel and had no idea that sick lit was even a thing. this is so interesting.

Really interesting to think about equating sickness with (gendered) power roles. I feel like there is probably a different but similarly problematic paradigm in “grownup” romance novels with women taking care of injured men. Sexy Nurse/Florence Nightingale territory – a mix of the woman being in service and not on the front lines, but also being capable, in control, dominant. And what about m/m “hurt-comfort” fan fiction written mostly by straight women — a whole ‘nother can of worms. I do remember reading lots of fantasy/adventure books when I was young, and I would daydream about being the male protagonist who, after being injured during derring-do, is nursed back to health by attractive male companion (so much of this was all-boys-club stuff, pre-Tamora Pierce)! Or I might be the rescuer — it was definitely some weird proto-way of thinking about desire and power in relationships, part retrograde/sexist and part empowering and queer. In any case, as with the McDaniel books, it’s all deliciously and safely not real — like you can be all serious and grown-uppy and have these deep, sad, dramatic thoughts but at the very safe distance of them being totally romanticized beyond recognition (McDaniels) and/or with swordfights and dragons and/or just through the compelling but temporary vicarious experience of a genuinely written protagonist. So there is a place for these sorts of “training-wheel” feelings but that place needn’t be exploitative, sexist, racist, heteronormative, etc.

this IS really interesting

I have never read Lurlene McDaniel. I do remember that one of my friends in junior high read her books solely, besides having to read “Hatchet” and “The Giver” for English class.

I always thought they looked so damn depressing! Give me a YA novel by Avi or Gloria Whelan ANY day!

Oh god I used to read Lurlene McDaniels books all the time in 6th grade or so. I think I knew they weren’t exactly quality literature even then, cause I would try to hide them from my mom when we were checking out at the library.

I think I need to revisit old times by playing this drinking game you mentioned….

Great article, Riese. I loved Lurlene McDaniel’s books when I was younger, and haven’t revisited them since…now I’m kind of interested to.

(Ditto Christopher Pike, who I remember as having written a lot of sick lit, but now that I’m looking him up I guess he’s more horror? hm.)

And I love your badass defense of TFiOS. Because it’s phenomenal.

I have a sister-in-law who used to read these books voraciously and bawl her eyes out. I always asked her why she read them if she was just going to cry but she loved them! Sadly one year on vacation I ran out of books to read and these were my only option. I made it through one book, and promptly told her they are horrible, depressing stories; I told her the girls in them sucked because they were weak and powerless. My opinion had nothing to do with the illness and everything to do with the dependency on the boys to come and save them. At the time I was all about Baby-Sitter’s Club, Carolyn B. Cooney and various fantasy books. I’ve never liked female characters that wait around to be saved by a men. Hell, my Barbies lived in an all-female dream house! I had no use for Ken (I should have seen the signs sooner, I know!)

As someone with chronic conditions I can say I look for ways to escape thinking about it more than I have to. I don’t want all my focus to be on my disability, I want to be me. Had I not had so much trouble with my health when I was a teenager I would have figured out my sexuality a lot sooner. As it was I had the thought, “I think I’m gay.” I literally shook my head and said I can’t deal with that right now. I’m sure there are plenty of teens who do deal with both and love to see themselves represented somewhere. After reading this I’m just not sure this is something that should be continued; at the very least it needs some major changes, at least in the YA sector.

I will have to check out The Fault in Our Stars and The Lovely Bones.

probably going to have to read one of these now. and t.f.i.o.s. don’t hate. *listens to vicarious by tool*

rachel i love you you sexy bitch

I don’t think it’s anything new that our culture has a love affair with suffering and death. This is just a different way to portray that desire to suffer and idolization of suffering.

Western Culture is based in Christianity and Christianity is based in the concept of suffering. Job is an excellent example of this and so is Jesus. Hearing a story about a man who is nailed to a cross and whose suffering is celebrated as the salvation of mankind should be no less scarring than reading a book about a girl who has cancer.

I remember trying to read one of these books back in middle school, but stopping because the idea of it made me so upset. My mother has always been unhealthy, and I myself suffer from a chronic illness. I was /definitely/ never treated like any of these girls in the books were, and it kind of makes me laugh to think that anyone would be.

Beautifully well-written article. That’s my girl!

i remember being so grossed out by these books when i was younger, but i always thought i was alone in that sentiment. it was just so frustrating to read these stories about beautiful, popular blondes who would just wilt upon the touch of the first terminal disease mcdaniel could pick out of a hat (and, of course, the inclusion of the handsome guy who’d delicately sweep her off her hospital bed and into his arms- GAG ME). it just felt like she was romanticizing these terrible illnesses for the sake of nothing. thank you for writing this; you’ve really helped me sort out what bothered me so much about her work. it’s good to know i’m not the only one who felt that way!

I’m fascinated by this article, and the comments. Though a prolific reader as a child, I wasn’t very cognizant or critical of gender stereotyping, racism, etc., and it’s interesting to reexamine the material of childhood from an adult lens.

In response to the article’s quote: “I mean, do McDaniel’s books offer actual comfort to ill children and their friends/families, or are they strictly voyeuristic?”

A close childhood friend with serious health issues read Lurlene McDaniel voraciously. Constantly surrounded by well kids who couldn’t really understand the severity of her situation or the different perspective it gave her on the world, I think it comforted her to escape into the head of other (fictional) young people who were experiencing the same kind of tumult and upheaval she was. Yes, they’re morbid, but I think that was part of the appeal. Despite falling prey to all the -isms mentioned in the article above, there was a certain reality and frankness to them, acknowledging that not everyone was going to live-happily-ever-after. That’s a lonely truth to have to confront at such a young age, and if these books made it a little easier for her, I’m grateful. For all their shortcomings, McDaniel’s books gave my friend what we all look for in books, especially as children — a protagonist who reflects who we are.

John Green makes me gag.

Oh my god. I thought I was the only one.

I apparently missed a lot as a child when I was reading margaret atwood instead…

(no one cares)

dammit Mary Poppins, where did you go

Whatever, this is my face right now:

I found this fascinating despite being only peripherally aware of the genre, and never having even heard of Lurlene McDaniel. I like her name.

Obviously these books seem particularly bad for their groan-worthy gender depictions, but these themes run deep through pretty much every other genre too.

I was debating with a guy at work recently, who reckoned he had raised his kids in a gender-neutral fashion. And then apparently his son just wanted to do “typically” boy stuff and his daughter “typically” girl stuff. Parents underestimate how pernicious and pervasive gender stereotyping is…and don’t know how much shit lurks in books like this.

I know the hilarious covers and trashy blurbs should probably serve as fair warning, but I can imagine people getting fooled into thinking a book written by a woman, with a teenaged girl protagonist that battles adversity might be an advert for female empowerment. Oh, how wrong.

I had completely forgotten about my obsession with Six Months to Live when I was in fourth grade! I read that book four or fives times, to the point where my teacher said other kids wanted to read it and I had to stop taking it for every “free reading” time because there were complaints.

I had no idea “sick lit” was an entire thing. This was really awesome, Riese.

I need to check with my wife, because she had a fascination with “illness” books as a pre-teen, but I’m not sure if McDaniel’s books were among her favorites.

She also has a thing for boarding school novels, and then there were the rare favorites that she had that were BOTH – sick girls at boarding schools! Yay! Apparently that was the shit.

I need to read some of hers to figure out what the fascination was. I was too busy reading Nancy Drew and pretending to be a girl detective.

Wow – “Beth March syndrome.” That’s so sad. I’m not invalidating it. It’s important to admit these fantasies/needs exist because they so plainly indicate the culture’s ongoing definition of “female goodness” (passivity/submissiveness). Girls fail at them and the inevitable corollary is self-hate. A fantasy is born: if only one could be good, if only one could be loved, perfect, complete…And it isn’t a far leap to death/self-obliteration at that point. But then the spiral continues downward, because who the hell’s going to be nicey-nicey like Beth March or the other “pure” (inevitably white) dying heroines?

These books are totally a form of gender policing, a way of making impressionable girls feel worse about themselves. (I mean the pulpy ones; I’ll take your word on it that Sebold and others are better than this.)

It reminds me when I was a kid (well, 14 or 15) and reading Jane Eyre. Helen Burns is another of this type, and while I recall admiring her, my admiration was about as brief as Jane’s, because I wasn’t as “good” as her. And one more invisible message about my inferiority was transmitted. (Of course Bronte’s book ends up

upending most of the idea, but it’s still there.)

Really good work though.

As someone with life-threatening medical problems (not using the word chronic for various personal/medical reasons)from around 2 to 18 (and still affects me a lot), I have always avoided books like these, especially as a young child/tween. They seemed to be one of those things that lure you in with ‘Look! Something that resembles your life!’ and turns out to be more shit written by people who have no experience with what you’re dealing with (I developed good bs detectors pretty early on in life). A lot of the criticism Riese and Grossman present is spot on, but looking at the books from my perspective, as someone who was very sick at a very young age, I have a couple of things to add. Keep in mind that that is all personal experience, from someone with no visible disabilities, looks white, and came from a middle class background.

From what i can see, and from my limited experience with books like these, these books manage to both romanticize death and not really talk about it without really going into what it means to be a dying child in a culture that more or less refuses to talk about death. Death and our cultural idea of dying, is a fairly taboo subject that is usually skirted around/makes people uncomfortable/whatever. especially if you are young. We never teach our kids about death and dying. As a kid who was very aware of the fact that she might die, and very comfortable with the fact (funny how several near death experiences as a small child will do that to you) talking to others, especially adults, about dying/death was pretty near impossible. This was a big deal to me, because the concepts of death/dying/being life threateningly ill were really essential to my experiences growing up, and the general refusal to talk about something that was an essential part of my experience made me feel even more ostracized than I already did. Not to mention the teasing from peers when they found out I was sick–I remember in 3rd grade after someone found out I was ill, my entire class refused to sit at the same lunch table as me for a week because they thought I might contaminate them, and the teachers didn’t stop them because they felt it was a valid fear. In books like these, the main character gets a boyfriend instead of bullies. In both of the reviews that I read and all the comments too, I’ve noticed that there also is a lack of talking about death, especially since the books being discussed are basically about, you know, dying children.

The other thing i find funny about these books is how EASY the diagnosis process is. I know it took me a year and a half to get diagnosed with Graves disease, and it was only so soon because my mom kept on insisting on seeing doctor after doctor until one decided that she wasn’t just being ‘an over protective mom’ (even though my heart rate was about 2 times faster than it should have been and I was losing all my hair, nbd) and decided to run some basic tests. I was talking with my WS professor last semester and it turns out she had a similar experience as a child, only with a heart condition instead of graves disease.

And that was a really long comment so I’m going to wrap it up, but I am sort of interested in checking out one of these things but also sort of terrified. I think I’ll keep Emilie Autumn as my go to for melodrama about death and illness. At least I can sort of relate to her.

also, I keep on rereading this article and I can’t figure out what the fuck The Lovely Bones has to do with the other books presented?

Ended up reading this with my mother, who banned Laurlene McDaniel after the first book I brought home (I think I finished that sitting on my play structure thing in the yard and cried, but I might be confusing this with some holocaust book). Mom says I cried when Beth died. We both did, actually, and apparently that was why she read it to me?

I picked up another L McD while serving jury duty this year. Oh my gawwwwwd. So bad. And then they got married and she rehabilitated his leg injury but the poor girl with leukemia from camp didn’t ever get to go to the wedding. And her friend was wearing a yellow ribbon around her neck because this Boy promised to send it to her if he took the test for the bad gene thing and found out he wasn’t gonna die. Yep. Healthy people gets married and lives happily ever after. In their early twenties..

The Beth March stuff is right on…there is a lot of weird stuff inLittle Women, but it’s still kinda a feminist book I think…

Ehhh, it’s really hard for me to read critiques of sick lit when there are sooooo few books about disability and illness. Yes the Dawn Rochelle series has serious problems AND it was also a breath of fresh air to me when I was dealing with health conditions and hospitals as a kid and didn’t see much representation of my experiences anywhere. I want to live in a world where we have enough stories about kids who are disabled, have cancer, have chronic illnesses, die young, etc. for enough of those stories to be non-oppressive in other ways, too.

I was in high school by the time Lurlene McDaniel published her earliest novels, therefore I was a bit too old for her formulaic “sick-lit,” which I think appeals more to grades 6-8. However, one of my favorite books as a teenager was “Eric,” a biography of a young adult in his late teens/early 20s who was diagnosed with ALL in the late 1960s, only days before his first year of college.

Written by his mother, Doris Lund, “Eric” is interesting for two reasons: it documents some of the earliest years of experimental, sometimes successful cancer treatment, and it portrays Eric as a real person, not an illness archetype. Although Eric eventually dies at age 21, throughout his treatments, remissions, and relapses he attends school, plays on his college soccer team, travels, and has at least one serious girlfriend. When an inpatient at a cancer-research center, he sometimes has an above-average sense of humor (for example, he puts goldfish in an IV bottle and eventually writes a comic-book series satirizing his oncologists), is at other times angry about his situation, and often just wants to be well.

http://stargayzing.com/beginnings-how-a-book-i-read-in-5th-grade-about-a-teenage-boy-with-leukemia-taught-me-my-favorite-chicago-song/

Recently, I also read Julie Passanante Elman’s academic paper “Nothing Feels as Real.” As an old English major who considered Marxist-feminist literary analysis a worn cliche’ during the late ’80s, I think Ms. Elman, who is probably at least ten years younger (and therefore was NOT a teenager during the Reagan era), entirely misses the attraction of ’80s sick-lit: yes, it involves capitalism, but not in the way she thinks.

Young women born between 1965-1975 were too late to really remember the Vietnam era, yet had neon daisy petals and peace signs floating in our peripheral vision. Still, we arrived just in time to experience the early benefits of second-wave feminism. We were not ignorant of history (our parents and grandparents remembered the Great Depression and WWII), and soon had our own mild crisis in Watergate, but for a few relatively-innocent years between Watergate and 1980, it seemed like people were really trying to evolve as human beings, not just as homo sapiens.

And then in late 1980, Reagan was elected. For young women, especially those who wore “ERA Yes!” buttons, Reagan’s election and the cultural changes that seemed to happen almost overnight were akin to a natural disaster. Suddenly the only things that mattered to many people were money, more money, and social status. Joni Mitchell was shoved off her piano bench, replaced by Madonna backed by an electronic drumbeat.

An introspective adolescent who cared mostly about books, art, and rather idealistic political issues, I’d worn the “nerd” stigma for years. In the 1980s, since my life goals did not include “upward mobility,” I became obsolete as well. My parents’ positive attention went to my high-achieving sibling; my father’s chronic illness and subsequent business concerns absorbed their negative attention. Neither a high achiever nor an overt problem, I was largely ignored.

At age 14, after a minor orthopedic injury, I was diagnosed with a small bone neoplasm. My x-ray was sent from primary care to radiology for an expert opinion, diagnosed two days later as a common, benign abnormality. During those two days I was somewhat less invisible at home, but what really embraced me was the knowledge that with a potential cancer diagnosis, my parents would finally be granted permission to love me as a human being. . .even if I wasn’t a “high achiever” with “upward mobility” as my polestar.

Earlier this year my young second cousin was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. I, ever a person who looks for a book in every situation, took to my shelves and other’s: I did not want a protagonist who was the problem, I wanted a hero who happened to have diabetes.

I found one book, which I’m still reading but don’t think it’d be all that interesting to a 12 year old girl. All the others can be summarized as “Girl is diagnosed with DIABETES. She STOPS PAYING ATTENTION TO HER HEALTH (before or after boyfriend). WILL SHE LEARN TO LOVE HERSELF AND TAKE CARE OF HERSELF BEFORE SHE DIES?”

Urgh. I’m now off and on working on a vampire spoof adventure with a diabetic protagonist. Might not be wanted or enjoyed by anyone but at least it’d make me feel less frustrated.

What perfect timing for this to show up in the archives links today. This is the first AS article that I remember reading – and this year, the 10th anniversary of the founding of AS, I’ve been thinking a lot about the early articles that drew me in to this site and community.