This review contains spoilers for the entirety of Harlots Season Two.

Season One of Harlots, a Hulu series produced and written entirely by women, captured me with its surprisingly authentic portrayal of indoor sex work. I was struck, last year, by how a story set three centuries ago could yank my mind right back to the massage parlor as urgently as running into a former client outside the 59th Street Bloomingdales (which, for the record, happened to me twice). With that basic groundwork so handily laid bare, I was struck, this year, by how Harlots’ sophomore season managed to set forth a story more applicable to the modern day than any of the dozens of deliberately-branded “#MeToo Era” episodes actually set in the modern day delivered this year.

Harlots becomes, like our very lives themselves in the year of our thwarted lordess two thousand and eighteen, the story of women, queers and people of color desperately clawing for some access to freedom — whatever that is or looks like, whoever actually has it. The ongoing turf war between rival bawds Lydia Quigley and Margaret Wells is framed within a broader context in which both women struggle for any genuine power or agency when the buck repeatedly stops before a group of sadistic wealthy white men who call themselves “Spartans,” and the men in their economic class and social circle who don’t care who they hurt.

“The Spartans were a superior race,” the insufferably handsome Lord Fallon explains to his mistress, Lucy Wells. “They killed their lessers, the Helots, as a rite of passage.”

“What made them lesser?” She asks.

“Their blood,” he answers, fingering his sword like something he wants to fuck.

Most of a prostitute’s clients, or “culls,” are relatively good guys. That was true then, and it’s true now. But the majority of men in power, perhaps due to, oh I don’t know, power tending to corrupt and absolute power corrupting absolutely, are to put it simply, not, and a lot of them are clients. Last year it was easy to say that powerful men like these — who casually organize recreational gang rapes of kidnapped virgins, and murder anybody who gets in the way of their plans — still exist. We knew some names, sure, but not like we do now. Now we know, beyond any wish to believe otherwise, that men like this make the movies we watch, tell the jokes we laugh at, control our government and lead our academies. Harlots, then, is a reminder of exactly how far we haven’t come.

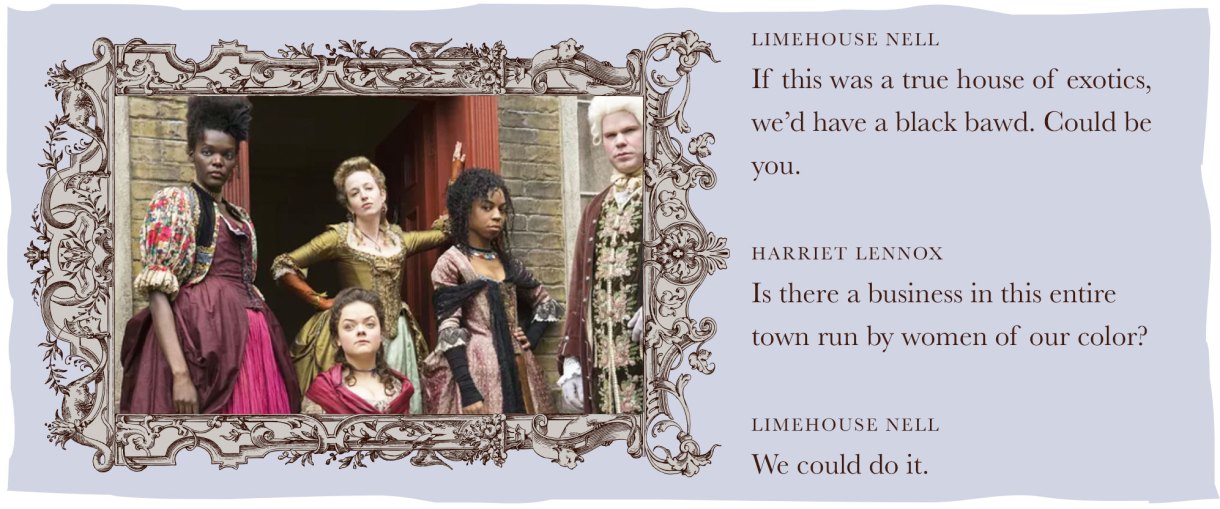

Sex work is the world’s oldest profession, after all, and due to its (usual) illegality and its very nature — selling what one sexually desires — it makes sense that it’d provide an ideal purview for “some shit never changes” revelations. Desire is notoriously resistant to politics and cultural evolution and so are underground economies, which don’t concern themselves with employment discrimination policies or sexual harassment regulations. Emily Lacey’s “House of Exotics,” in which she employs two Black women and one little person, could easily exist today, as regressive as it sounds. It remains true that the official legal authorities are notoriously uninterested in pursuing the murderers of sex workers, as with Kitty in Harlots, and workers feel they have to take justice into their own hands. It’s no wonder when contemporary showrunners want to make a statement about the nature of man, the danger of power and the fallibility of humanity through science fiction, sex workers always turn up — look at The Handmaid’s Tale, or Westworld.

Regardless of the era, legal and cultural reactions to sex work and workers lay bare conceptions of who is worthy of agency, of respect, of self-determination, of basic safety to their physical beings and the expectation of that safety remaining constant. Even a society that seems safely stratified — prostitutes are dirty and deserve what they get, while purer women are at least deserving of mourning and pity if they’re harmed — isn’t as stable as it seems. Part of the social function of the stigmatized prostitute is to provide civilian women a role to fear stooping to — as Season Two shows us with the increasingly slippery positions of sex worker-adjacent women like Lady Fitz and Amelia, or Lucy with her aspirations of rising to a life where she has power unsullied by her family’s industry.

If Season One was about sex work, Season Two is about the reality that what’s done to sex workers is inextricable from what’s done to all women — the lessons about power, violence, solidarity and struggle in stories about sex work are ones that the larger conversation about gender ignores at its peril. Sex work remains an illuminating and superior lens through which to take stock of the restless, uncomfortable gender dynamics and power structures that may experience shifts in style or public acceptance, but never by degrees of import or influence.

But Harlots also flips us over, revealing the soft underbelly of this hard life: the respite of chosen family and the intensity of those bonds, more genuinely rewarding and life-sustaining than those that unite sin-soaked, supremacist brotherhoods. Women look out for each other, break bread together, start their own houses of ill-repute together. The only men any of these women rely on are either gay or Black, and Season Two adds another Black male character on top of Will North, Maggie Wells’ common-law husband, and their son Jacob — Noah Webster, a former soldier who now makes a living fighting at the local tavern, technically “free” but still barred from most avenues of employment. We’ve also added Nell, a black woman recruited to the “House of Exotics” by Emily Lacey, where she and Harriet quickly become friends and begin dreaming for a house of their own. We deserve a Season Three to see that aspiration fully realized — as it’s likely Harriet is based on “Black Harriot,” who became London’s first and only black madam in the 1770s.

Still, aside from the rocky but steadfast connection between Maggie and Will, the most treasured bonds remain those between women, highlighting the entrepreneurial, conspiratorial and yes, sexual, freedom women can find only with one another.

Within this context, it’s fitting that Season Two is properly queer whereas the first was only occasionally so. It felt like too much to ask that the crackling sexual tension between Liv Tyler’s understated Lady Fitzwilliam — wealthy beyond measure but unable to access her own fortune, guarded carefully by her Head Spartan brother — and prized prostitute Charlotte Wells would ever come to bear upon us all, but indeed it does. After so many years of self-imposed celibacy following the incestuous rape that led her to birth a daughter she’s never met, Lady Fitz chooses to have actual sex for the first time with Charlotte, who offers herself with faithful interest and devotion. A man cannot undo what her brother had done, but a woman? A woman had a shot, and a woman hits a nice homosexual home run for us all.

There’s more queerness where that came from, of course. Violet is back, landing herself in jail for petty theft in the first episode, then rescued by her beloved Amelia’s entreaty of the new Justice, Josiah Hunt, to hire Violet as household help rather than shipping her off to America, where she would undoubtedly be sold as a slave. (Although Violet points out that her situation with Justice Hunt has a lot in common with slavery.) In this new space, Violet and Amelia have slightly more access to one another, but there’s more scrutiny, too. Violet, forever having fended for herself, has to prioritize survival, whereas Amelia, raised puritanically, is carried away by her first tender steps into a world of unbridled emotion. She wants more of it, and now, but Violet’s instinct is to take a step back and protect Amelia, even encouraging her to accept Justice Hunt’s proposal of marriage.

Perhaps one of the show’s most tender connections is that between Amelia and Prince Rasselas, a gay street kid who lost his “sweet boy” to illness and is the only person Amelia knows who might understand her inner turmoil. Now that her mother has caught wind of her affair with Violet, their time together feels dangerously limited, and both struggle, again, against a ceiling preventing any true agency.

Which brings me to our final queer character, if I may: Nancy Birch, who I’ve previously described as Pirate Dominatrix Laura Benanti. Nancy Birch, perpetually scowling and disheveled like a girl who couldn’t be bothered to fix herself up for work after a night at Tunnel. Nancy’s ready to launch an underclass uprising at poor Kitty Carter’s lovingly slapdash funeral, dressed like fucking Captain Hook, responding to Margaret Wells’ declaration that Kitty Carter was innocent with, “Kitty Carter was guilty of the worst crime you can commit! The crime of being poor!” They rile up the distracted crowd: “We are a sewer full of rats being ruled by a handful of foxes!” Ironically and tragically, Nancy’s punishment for disturbing the peace in this manner is similar to what so many men have paid her to do to them: she’s cuffed to a pole and flogged. Like so many brief, inspired protest movements, the post-funeral uprising is squashed before it can even get wings, and things continue apace. Physically destroyed, Nancy holes up in Greek Street to heal. As Lucy, Charlotte and Will come to check in on her, their familial bonds set us up for the final two episodes of prison visitation by the same cast of characters. In those final episodes, Nancy’s long-swelled feelings for Maggie, who is like a sister but also something more than that, give us the season’s biggest tearjerker.

Although Margaret Wells remains a frustrating antiheroine, foolishly punting her faithful husband out of her house on suspicions he’s got eyes for Harriet (who she throws out too, for good measure) in the first episode, because he dared to help her not lose her children forever, and is seemingly unable to resist the urge to yell at her enemies in public, her wrested lot in life is downright holy compared to Lady Quigley’s. Lesley Manville outdoes herself at every turn, playing a bawd ultimately no better than the men she serves — although she’s at least ultimately vexed to find herself, when it’s all said and done, swiftly rendered powerless and robbed of agency on account of her gender.

Near the end of the season, Emily Lacey is forced to confront her girl Cherry for spying on her at Lydia Quigley’s behest. “My Ma was small,” Cherry says, regrettably. “She always told me; ‘any flotsam passing, you cling to it. You keep yourself afloat.’ I chose the wrong raft. I’m sorry.”

It’s a quick scene without much consequence, and despite the girls of Harlots generally erring on the side of eternal grudges and fiercely-enforced loyalty oaths, Emily gives her a pass, citing Charles’s soft heart and the opportunity to double-cross Quigley with a spy switching sides. But maybe Emily is sympathetic to her plight, in a way, having once landed at Quigley’s herself under similar auspices.

Cherry manages to capture so much about this world in that line, though — any flotsam passing, you keep yourself afloat. And it is picking the wrong rafts that so often gets these girls and their associates in trouble, after all — or maybe it’s not the wrong rafts. Maybe it’s that rafts are all there is to float on, and that off there in the horizon, every man in power is trawling the deck of a leisure cruise, eating grapes off the genitals of a naked woman, prone for his pleasure.

Lydia Quigley’s decision to harvest and present, for the raping, a young girl who thinks she’s been hired as a servant, is what finally pushes her remaining allies over the edge. Again, this serves as a handy allegory for much of what’s gone down in recent history — a serial predator, never having been punished for their misdeeds, takes things just one step too far and loses their loyal confidants. It is a group of women and Black men who devise a plot to thwart the sexual assault, but Quigley senses something is amiss and stops it in its tracks. The dominoes in place, everything comes tumbling down, leading to a finale as devastating as it is hopeful, leaving us all hungry for more. There were moments in that final hour — like the one where they’ve got Lord Fallon tied up, before the moment when they leave him alone there and it’s obvious he won’t stay — that had me literally cheering like a football fan.

Basically, what I’m telling you is that stories about sex workers are not niche, they are transcendent and universal, and often the truest and most enduring stories about Western Civilization ever told.

Amazing show, amazing review. I watched the entire two seasons in one weekend and it broke my heart a thousand times over in the best of ways.

I really need a third season, for these women, and also for more of your writing about this show.

Harlots is continuing the disturbing trend of UK-made TV programmes that aren’t actually available to legally watch anywhere in the UK! (see also: Killing Eve, although that finally has an airdate now)

I have nothing useful to contribute I am just extremely grumpy, but I appreciate all the parts of this post that I arbitrarily decided didn’t contain spoilers and thus could read.

I think you’re gonna like Killing Eve

okay now I want to watch this show… Good job, Riese.

Great article Riese. This season was even better than the first, and much gayer. I love how nuanced every character is – even as they make terrible decisions you can emphasize with them and the lack of options this society has left them with. Here’s hoping for Season 3!

Thanks Riese, this review is excellent. My expectations were already high for Season 2 and Harlots managed to exceed all of them.

I guess that’s what you get when you have a show directed, written and produced entirely by women. We saw all-female directors on Queen Sugar and Season 2 of Jessica Jones but there’s only so much they can do when those episodes written and produced by men. And then here’s Harlots. Produced by: 6 women( two of them creators and showrunners) & 0 man, written by :5 women & 0 man and directed by: 4 women & 0 man.

And then there’s the cast. It’s great to see a cast filled with women of all shapes, ages and sizes.

NANCY BIRCH FOR PRESIDENT

OF MY PANTS

Ditto. I can’t breathe when she’s on screen. Swoon! *fans self*

I thought Limehouse Nell gave Maggie some competition for “Harlot Least Likely to Keep Her Mouth Shut in the Face of Injustice.” She had literally zero f*cks to give.

I’m so bad at remembering to watch all the shows I’m interested in…..but dang does this make me want to watch. Riese, as always, your writing about tv is superb

Just watched this whole season after reading this article. Was not disappointed!! Everyone should watch this show now.

Please let this show live!

I loved this show so much. Thank you for this great article.