“I’ll always remember the first time I met her. She made such an impression on me. She stretched out her hand and she said, ‘Hi, I’m tatiana de la tierra and I write cunt stories,” writer Olga García Echeverría told me, summing up tatiana de la tierra’s brassy swagger like only a lifelong friend can. As a writer, activist and professional lesbian, tatiana de la tierra changed the landscape of feminist publishing. She grappled with interlocking identities, colonialism and intersectionality; created the spaces Latina lesbians needed to bring their whole selves to the table; and manifested vibrant, accessible and visible queer communities on a transnational scale through zines.

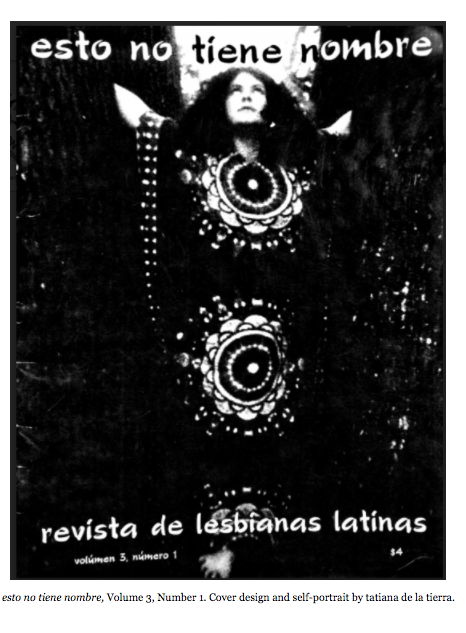

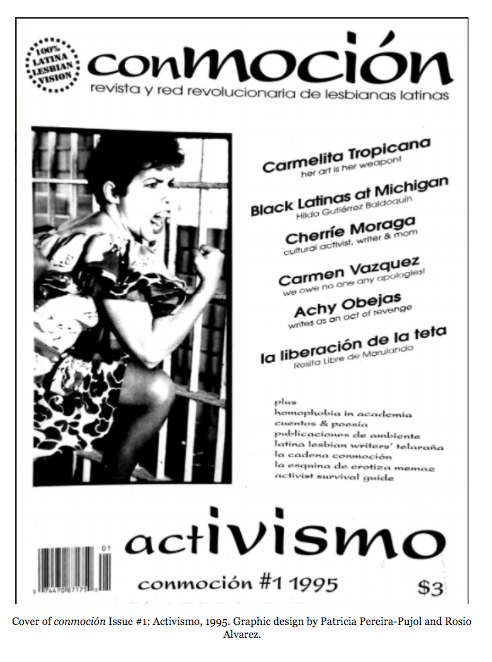

The first zine you’ve probably never heard of was esto no tiene nombre (“this has no name”), founded in 1991. The second, launched in 1995, was an ambitious reincarnation of esto called conmoción (“with motion” and a pun on “commotion”).

“Surrounded by stacks of books, family photos and pandebono, esto and conmoción moved me. I fell into queer space and time and landed in the hard-edged, punk-tinged moments of Latina lesbian feminisms. I was witness to a group of vibrant, incendiary women making and sharing their own culture. I was hooked.”

Over 20 years after the last issue of conmoción, I visited de la tierra’s mother, Fabiola Restrepo, in Miami. I wanted to know more about de la tierra and the zines I had found exactly nowhere online (though there’s a full set at the de la tierra archives at UCLA). I wanted to close the generational knowledge gap around her particular Latina lesbian cultural production for myself. Surrounded by stacks of books, family photos and pandebono, esto and conmoción moved me. I fell into queer space and time and landed in the hard-edged, punk-tinged moments of Latina lesbian feminisms. I was witness to a group of vibrant, incendiary women making and sharing their own culture. I was hooked. Here’s what I learned.

tatiana de la tierra was born in Colombia, 1961, and by age seven immigrated with her family to Homestead, Florida. It was in this “redneck terrain” that de la tierra decided to learn, and weaponize, the English tongue. (Later, she’d eroticize it, quipping, “Why not admit that the tongue is the lesbian mascot?”) By 1984, de la tierra graduated from the University of Florida and threw off the ball and chain that was formal scholarship and nerdy boyfriends. Embarking “on a Spiritual Journey that led me to Dianic witchcraft, feminism, and ultimately, lesbianism,” de la tierra hit the road in a VW bug and pursued her lesbian feminist education.

Jumping from city to city, she followed the women’s musical festival circuit. The festivals were a culture, societies even, all their own: women-run and women-only hotbeds of politics, debate and discovery. At the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival of ’87, in the middle of ten thousand women — naked, muddy, druggy, horny and mostly gay — de la tierra saw a sign that read “women of color, let’s get together” and “felt this immediate wow.” On the festival circuit, she developed her woman-of-color consciousness, realizing the power of space and solidarity. Then, as fate would have it, she met Juanita Ramos, the editor of the upcoming groundbreaking anthology Compañeras: Latina Lesbians, while couchsurfing through New York City. Compañeras would be where de la tierra’s first poem, “De Ambiente,” was published.

Between crashing with Ramos, jumping into lesbian-feminist music culture, and seeing the call for WOC organizing at MichFest, something clicked.

Enter esto.

Co-founded by de la tierra, her lover Margarita Castilla, and then-girlfriends Vanessa Cruz and Patricia Pereira-Pujol in 1991, esto no tiene nombre was de la tierra’s next life juncture. The collective was not just influenced by lesbian-feminist values, but actively shaped them: esto was horizontally structured, volunteer-based, and offered sliding-scale subscriptions. As for publishing in Spanish, Spanglish and English, they wrote:

Co-founded by de la tierra, her lover Margarita Castilla, and then-girlfriends Vanessa Cruz and Patricia Pereira-Pujol in 1991, esto no tiene nombre was de la tierra’s next life juncture. The collective was not just influenced by lesbian-feminist values, but actively shaped them: esto was horizontally structured, volunteer-based, and offered sliding-scale subscriptions. As for publishing in Spanish, Spanglish and English, they wrote:

It can’t be said that the “official” language of our community is either English or Spanish because this would exclude many. And if it’s a question of being P.C., neither is more correct than the other; both are colonizing tongues… As Latinas from the US and Latin America come together, we will naturally move towards speaking Spanglish. ¡Qué viva el Spanglish!

Releasing a cool nine issues, the zine recognized the Latinx diaspora and its many languages, histories and contradictions. Self-publishing, Echeverría told me, also resisted the exclusion facing queer Latinx women who wanted to write, make art and organize on larger platforms: “For tatiana, that’s what she was saying: fuck you to the establishment, especially in publishing.”

But all this trailblazing led to trouble. esto was originally a newsletter for Miami’s first-ever Latina lesbian social club, las Salamandras de Ambiente. “De ambiente” is queer code for “in the life” and, according to Cruz and Pereira-Pujol’s (faulty) research, salamanders were honorary lesbians “blessed with the mythical ability of being able to live in fire.” But las Salamandras couldn’t quite take esto’s heat. de la tierra’s review of the lesbian sex tapes “Bathroom Sluts” (“good intentions, but left me dry”) and “Dress up for Daddy” (“a modern expose on the internal game of butch/femme… electric and intimate”), for instance, scandalized many members. The collective’s agreement to publish one orgasm per issue didn’t help.

“de la tierra, with her smut, Spanglish and creativity, was shaping culture and creating a meeting point for a generation of writers and artists.”

Many las Salamandras members were closeted, and their ideas of sexuality “did not include challenging the social construction that kept lesbianism a private matter.” esto’s thought differently. de la tierra, Pereira-Pujol, and Cruz were creatures of the far left, while Castilla was Cuban, Christian, and ultra-conservative — but also butch, walking “the streets of La Habana arm-in-arm with her female lovers,” in a place and time where doing so could cost your life. The four creators of esto could handle some push back. The las Salamandras members were another story, and held a secret meeting, formed a task force, and gave an ultimatum: break up esto or break ties with the social group. esto broke away, and finally free from censure the zines, orgasms and women kept coming.

But it wasn’t just cheeky reviews and sex. The collective took playfulness and joy seriously because it contrasted heavier realities of daily racism, xenophobia and heterosexism. They leaned into the hard work of decolonizing history, queering literature, exploring latinidad and lesbianism. And at a time when it wasn’t okay to be either let alone both, esto was a radical answer to invisibility. The dialogues reflect not only the cultural crises of 1990s — including BDSM and HIV — but also the changing understandings of lesbianism. In a letter to conmoción, one writer said:

I was really surprised to receive tatiana’s note regarding my submissions, with the statement that a “dick” in one story made you question whether or not I was really familia… Por supuesto que soy jota! (“Of course I’m a dyke!”). But that doesn’t change the fact that desire exists in many sites for me. That most lesbianas I know have sex with men in one way or another. And if you read the piece, it’s not just about a good, clean jotita fun or about straight sex. It’s about power.

The editors replied that “being in a position of censorship is bizarre and disturbing… but the content has to be lesbian.” There’s plenty of room to critique the decision, the problematic assignation of “dick” as antithetical to lesbian, but critique is the sibling of engagement. Before esto, there’d never been a literary space to even have these conversations.

Meanwhile, the four editors went unpaid and worked full-time jobs elsewhere. de la tierra was a perfectionist and pushed for incorporation and grant writing; pressure was building over the zine’s mainstream direction, finally blowing in the summer of 1992. That year Hurricane Andrew, a category 5 storm, destroyed not only Cruz and Pereira-Pujol’s home, but also Margarita and tatiana’s relationship. Castilla left de la tierra for another woman; she’d seen de la tierra promoting the zine on Telemundo and got Castilla’s number from there. Yikes.

Still, Pereira-Pujol told me, “ours was a spirited and passionate collaboration that happened almost by fate… tatiana used to say we had shared the same passionate and spirited relationship in past lives and sometimes I believed her.” de la tierra, Castilla, and Periera-Pujol stayed in touch, circling back to one another as much as their divergent paths allowed. From Cruz, there was only radio silence.

In 1995, with a grant, co-editor Amy Concepción, and esto co-creator Pereira-Pujol’s help, de la tierra launched esto’s bigger, badder follow-up. conmoción had a website for Latina lesbian writers, La telaraña, as well as the newsletter el telarañazo with events and publishing opportunities. de la tierra, with her smut, Spanglish and creativity, was shaping culture and creating a meeting point for a generation of writers and artists. Lambda Literary finalist Juana María Rodríguez, Pulitzer Prize winner Achy Obejas, performance artist Carmelita Tropicana, queer photographer Laura Aguilar, human rights activist Luz María Umpierre-Herrera and canonical anthologist Cherríe Moraga all found their way to esto and conmoción.

In 1995, with a grant, co-editor Amy Concepción, and esto co-creator Pereira-Pujol’s help, de la tierra launched esto’s bigger, badder follow-up. conmoción had a website for Latina lesbian writers, La telaraña, as well as the newsletter el telarañazo with events and publishing opportunities. de la tierra, with her smut, Spanglish and creativity, was shaping culture and creating a meeting point for a generation of writers and artists. Lambda Literary finalist Juana María Rodríguez, Pulitzer Prize winner Achy Obejas, performance artist Carmelita Tropicana, queer photographer Laura Aguilar, human rights activist Luz María Umpierre-Herrera and canonical anthologist Cherríe Moraga all found their way to esto and conmoción.

Behind the scenes, de la tierra struggled with chronic illness. Diagnosed with lupus in 1990, a flare up around the time of the third issue nearly cost de la tierra her life. It was a sign of more to come. In 2001, she was hospitalized in Mexico while promoting her book; in 2009, her kidneys began to fail; and in 2012 she was diagnosed with stage four cancer. Knowing the scarcity of Latina lesbian community spaces and that she was running out of time, de la tierra’s output had urgency.

Eventually, conmoción became too much to manage. de la tierra decided to “sombrarme en el desierto y aterrizar en los cosmos,” or “ground myself in the desert and land in the cosmos.” Which meant she decided to go to grad school in Texas. At the country’s only bilingual creative writing MFA program, de la tierra developed what would ultimately be her most defining collection: For the Hard Ones: A Lesbian Phenomenology / Para las duras: Una fenomenología lesbiana. In it, she praises butches, femmes and queers with gender “like clay,” all the while creating and depicting an iridescent lesbian paradise. She interrogates power, flips the script on poetic form, and opens meaning between the Spanish and English versions of each poem. She made lesbian existence accessible and multilingual, and did so in an environment historically hostile to women, people of color, queers and immigrants. The book’s presence in a classroom setting was rare and validating; students were brought to tears.

“With life-altering conversations around who has the right to occupy “American” geography and culture, and who has the right to be valued and live well, it’s imperative that we not resign to silence as our story.”

de la tierra’s lifework was part of a movement that brought intersectionality to the mainstream. Hers is a legacy of stage-setting, of paying forward a little more breathing room for future queers and creatives. With her passing in 2012, I’m left with a contradiction. After so much space creation, why does her death leave vacancy? Why is she not present in queer memory?

We — us, our generation, the ones that follow — aren’t really talking about her.

We know that the words of a combat femme, writing in English, Spanish and Spanglish are not outdated. We know zines, feminism and intersectional spaces matter more than ever. We crave that esto no tiene nombre, conmoción and For the Hard Ones / Para las duras. And with life-altering conversations around who has the right to occupy “American” geography and culture, and who has the right to be valued and live well, it’s imperative that we not resign to silence as our story.

Power want us to forget.

We, as younger queers, must rage against cultural amnesia. We must revel in the retelling. Our critiques must get messy and expansive and immersed with/in the contextual. We must zine and write, create and curate. We must look back while looking ahead.

We must remember tatiana de la tierra.

In April, 2018 Sinister Wisdom and A Midsummer Night’s Press released de la tierra’s For the Hard Ones: a Lesbian Phenomenology / Para las duras: Una fenomenologia lesbiana as a Sapphic Classic reprint.

Thank you soooo much for this!!!

I’m glad you liked this article! You can read more of de la tierra’s work on her website delatierr.net and I can’t recommend her collection For the Hard Ones / Para las duras enough!

This was informative read. Thank you.

Great article. I’ve been meaning to pick up a copy of For the Hard Ones ever since I heard someone read de la tierra’s “Ode to Unsavoury Lesbians” at a Sinister Wisdom event a few months back, but it fell out of my consciousness. I’ll remedy that now though!

So glad to hear you’re getting For the Hard Ones! de la tierra was also published in Sinister Wisdom Issue 51, among others : )

hi this might be a silly question: what was the reason for not capitalising tatiana?

Not at all!

tatiana de la tierra changed her name as an adult. de la tierra means “from the earth” in Spanish. There have been many feminists who have chosen to use only lowercase letters for their names or to change their name to re/claim their identities as feminists, women of color, etc. bell hooks is a great example and has written extensively on her decision to do so. Language is symbolic of power (racialized and gendered power especially) and lower casing intentionally messing with that.

Hope this helps xx