When The L Word: Generation Q premiered in December of 2019, it promised to portray a queer community more authentic than the original series. Trans people would not be a curiosity or a punchline, but an integral part of the show — and all trans parts would be played by trans actors. But lost in all this eager discussion was the person who played Max, the show’s most notorious trans character. Like when the series aired, lost was the humanity of Daniel Sea.

The press called Daniel cis because it fit their narrative of progress. But Daniel is not cis. Daniel is trans and non-binary and gender expansive. It was easier to scapegoat the face of the character than engage with the complicated harm caused by the people who wrote him — some of whom remain producers on the new series.

As trans actors get cast in more and more projects, I think it’s important we’re honest about the difficulties that often accompany that position. Even the most well-meaning cis people write characters who are inauthentic or create sets that are not safe. If we are going to move toward true progress, it’s important we’re honest about the past — and the present.

I first started talking to Daniel in January of 2020 and I am so grateful they’ve agreed to do this interview with me. I’m excited to share their story and offer a perspective on The L Word that has been absent for far too long. We can achieve so much more for queer people on-screen and off. But, first, we have to have the conversations.

Daniel: My goal with this interview is just to have a conversation with you. And hopefully clarify some things for people — not just regarding my gender identity but also where I’m coming from culturally and historically.

Drew: My thing is I’m always writing for people who read the article. I think a lot of internet writing is for people who read the headline and I’m lucky that Autostraddle by the nature of being independent allows a greater level of depth than that. And I think people who care about queer culture and queer media will appreciate the context you can provide. The first time I watched The L Word I felt a sensitivity in your performance that didn’t necessarily fit into the world of the show. And even as I was frustrated with where the story went I always liked Max and I always cared about Max because I felt an authenticity and a level of truth there. Getting to know you and finding out more about your background is clarifying in a way that makes me appreciate the show more and makes me appreciate what you went through. I want to share that with people.

Daniel: Thanks Drew. I appreciate that.

Drew: I’d love to just start from the beginning with your childhood and adolescence. And you can frame that however you want to. Your relationship to gender and sexuality, sure, but most people don’t even know your basic history.

Daniel: Growing up, I was a very physical kid. I liked to surf and swim. I’m white and I grew up in the suburbs outside LA, a place I later learned was intentionally segregated to be mostly white. It was pretty rough growing up queer and trans in that world in the 80s. I was a poet and interested in things that were quite eccentric in the hyper-materialistic Reagan era. I was bullied for being a “tomboy” and “weird” and eventually found refuge in books, punk, and a few good friends who were also outsiders. They gave me ideas of what was possible.

I left home at 16 and moved to the San Francisco Bay area which had a great punk scene. I got politicized pretty quickly: seeing people like Angela Davis speak, getting involved in the People’s Park demonstrations, cooking and serving food with Food Not Bombs. I also found The Gilman Street Project, an all-ages, self-organized venue where I played my first show at 19 with my band The Gr’ups. Our club was queer, political, and goofy. And most of all, filled with a lot of kind, outrageous, and creative people. It was about the whole scene we created, volunteering, living together in collective houses, and playing wherever we could make a show: 24-hour laundromats, backyards, in the traffic meridian, anywhere we could find an electrical outlet.

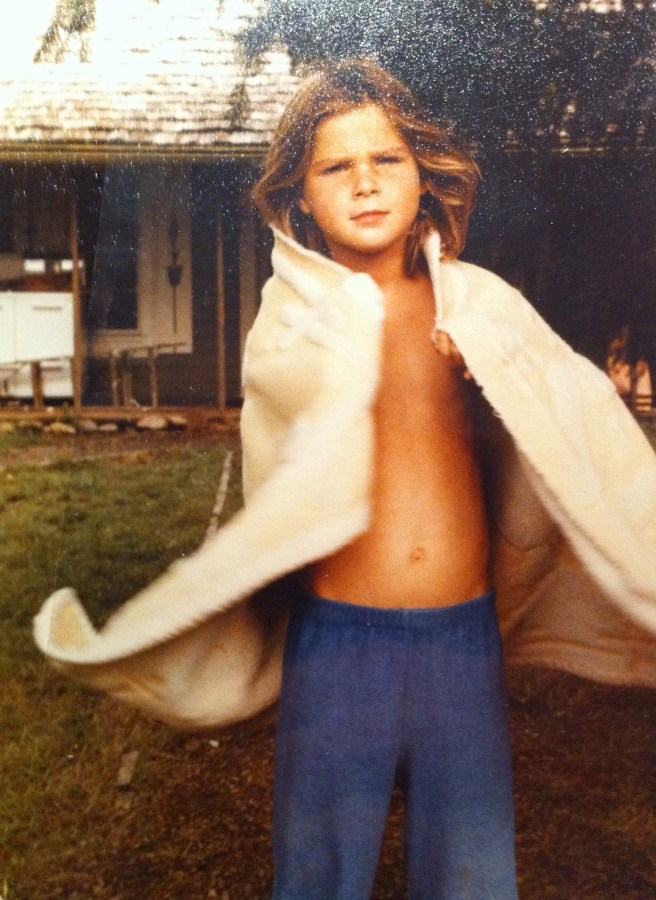

Daniel at age 7. Photo by Stuart Muller, Daniela’s Dad.

Drew: What was your understanding of your identity when you were first in the Bay moving through those spaces?

Daniel: Something I’ve been mulling over recently is how my gender and sexuality are interlinked with community. I think the word I’d use for myself today is something like pansexual. I had sexual experiences with all different genders growing up. And for myself, I always identified with this idea of a sort of princely warrior. When I had fantasies as a child, I always wanted to be the strong one who came in and saved the day. And the connections I had with cis men in my early years were really beautiful. But as we got older, I was expected to play a certain role that didn’t feel expansive enough. That’s when I found the queer community.

And we did call ourselves queer even in 1991, because we were living outside of the mainstream. We refused to compromise to the oppression we faced and we tried to live in ways that questioned those dominant structures. Folks a bit older than my generation formed Queer Nation and I think that’s how we started using the words queer and dyke to describe ourselves. We had a monthly music night at the Epicenter Record Store collective called Q.T.I.P.: Queers Together In Punkness. Our community was intergenerational and diverse in terms of gender and sexual identities that were in constant flux. The thing that I was drawn to in these scenes was the quest for true liberation. Do we have to work 9-5 jobs or do other alienating, capitalist labor? Could we figure out other ways to live together and care for each other outside of competitive heteronormative culture? I was raised in a culture that expected me to get married to a man, as a cis woman, have kids, and work within the system. One of the greatest gifts for me of the queer and punk communities was to show me we could search for viable alternatives.

I started studying theatre at a community college in Oakland that was part of Peralta Colleges which includes Merrit College, home to the Black Panther Party. This is important because all of this talk of liberation and what changed and moved me in this time was in large part due to the prior freedom struggles. We followed in the footsteps of the 1960s and 1970s radicals, like the Black Panthers, lesbian collectives of the east bay, the anti-war and free speech movement, to struggle for another possible world.

And my gender was being affirmed by those around me in both a personal and experimental way. I started to see examples of who I could be. And people also saw things in me I didn’t even see in myself yet. Like some of my friends would use he pronouns for me. It was serious and also playful. You have to remember this was before the internet was more than email addresses and some message boards. But we just had this communal understanding of what we were doing, you know? We were creating a world together.

By the time I was coming into TV in 2006, I’d already been living and playing in these realms for 15 years. I spoke about gender identity, sexuality, and my past with journalists and people in Hollywood who just didn’t have the cultural understanding of where I was coming from and were not familiar with the queer language I was using. It was a culture shock for me.

Drew: Do you remember how you knew that the Bay had these kinds of spaces? I mean, obviously San Francisco has an association with queer culture, but do you remember how you knew it was the kind of queer culture you were seeking?

Daniel: It’s actually a very visual moment. So my dad is gay. And my uncle is also gay and lived in San Francisco. He and his partner Steve had a bookstore in the 70s called Paperback Junction and they knew Harvey Milk and were involved in the gay liberation struggle. So I already knew there was stuff going on in the Bay that was different from LA. But there was one specific moment when it was clear to me that I belonged there. I was 8 years old and I was visiting my aunt Liz who lived on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. At the time, there were tons of street vendors, Dead Heads, punks and other people living in People’s Park. There was just a lot of energy going on right below her window. My dad bought me these glasses made out of silverware and I remember thinking the woman who made them was incredible. There was something in the way she was that just offered a different possibility. A liberated and free feeling that was contagious. I remember looking around and thinking: these are my people. This is where I could feel at home.

I fantasized about “up north” throughout my childhood and when I finally moved there my mind was still blown away by what was possible.

Drew: It’s so interesting to me that your dad is gay. You said your childhood was still rough in regards to being queer and trans. Were you getting that from him because your queerness was less conventional or were you getting that from everyone but him?

Daniel: The main place I got it was just from society itself. My parents were involved in the 1960’s youth movements, and they were artists. In fact when my dad came out to my mom, she was quite understanding and accepting. We lived with my dad, his boyfriend, and my mom for a year when I was 4.

My dad identifies as both a gay man and queer, and my parents always encouraged me to be myself. They didn’t force me to wear clothes I didn’t want or do any of the girl things. Except I had to wear a dress when I went to see my grandparents once a week. That was always a fight. But they called me a tomboy, and they’ve always been very supportive of me. They have always been kind and encouraging, and have always said that their main desire for me is to be happy and true to myself. They were living out their own lives in the pursuit of being true and being kind, and I definitely try to follow their example.

Drew: That’s lovely.

Daniel: My dad is an artist, photographer, and a psychologist, and just a free thinker as he would say. He took amazing portraits of us when we were young. His work is seminal queer work based in queer family and love. I felt very seen by him in this way. My mother is a poet and musician with a good spiritual foundation. My father’s longtime partner is a creative designer and my mom’s second husband who raised me was a writer and quite politically engaged in left politics. This psychedelic, artistic, political, and experimental familial background left a lot of doors open for me to experiment with my gender expression and life choices, even before there was the kind of language we now have to describe it.

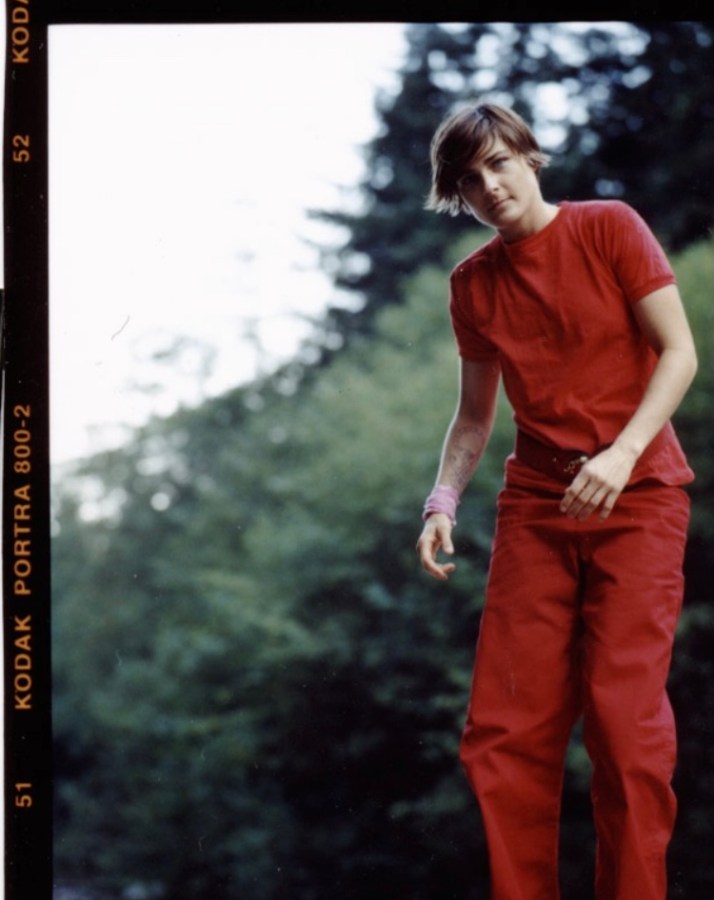

Daniel at age 18 in Berkeley, CA. Photo by Aaron Cometbus.

Drew: Wow okay so you have these parents who are outside boundaries and then you’re in this artist community that’s outside boundaries and then you get into a TV world that… probably had a lot of boundaries. I imagine that was challenging. When The L Word first came out was it on your radar? How aware of it were you?

Daniel: I didn’t hear about The L Word until the premiere of the second season. I was living in New York and my friend John Cameron Mitchell — who was the person who gave me my first acting gig in Shortbus — invited me to a watch party. I had never seen it. He just said it was a show about lesbians and his friend’s best friend was acting in it. I went to the gathering and to be honest I got really upset while watching it. In that particular episode, the characters were behaving in this way that felt like the LA I grew up around — petty in-fighting, intense and superficial, and alien to my own experiences of being queer. When I saw this representation after having been in such a deeply supportive community where we had cared for our friends who were dying from AIDS, where we had faced so much trauma collectively, I decided I couldn’t watch. I was with all these cis men who were enjoying the drama saying things like “OH GIRL” and after a few things under my breath I just got up and went to clean the kitchen. Later I came to understand the significance of what The L Word offered in terms of representation, but my initial reaction, just to be honest, was to bristle. So it was a trip when less than a year later I had this opportunity to audition for it.

When I was younger, at the time of the show, I made the mistake of distancing myself from TV and Hollywood. I was trying to describe where I was coming from and I think that came across as me saying I was above it all or like I didn’t feel like I was part of it. But I am part of pop culture. I’m just also a lefty Bay Area freak. That’s my reference. This show represented a completely different world. I understand there were communities closer to what The L Word showcased, but I was a child of hippies, punk rock, and raised by my lesbian and queer elders to think critically of competitiveness and mainstream culture.

Drew: Sure! I don’t think it comes across that you feel above it all. It’s just a very different queer community than the one that you were coming out of. And I think so many of the difficulties — definitely on screen and maybe off — came out of this attempt of a certain type of queer community trying to represent a different type of queer community. And I don’t think that has anything to do with a dismissal of pop culture as much as an honesty around what aspects of the queer community get centered in pop culture. That’s a conversation people have been having for decades but maybe the mainstream is finally having it too. And I think it’s important to be honest about that. It isn’t personal. It’s not a critique of any one show or any one person. It’s just an exploration of where we were almost twenty years ago and where we are now. How does pop culture function in our society and who does it represent and who does it not represent, you know?

Daniel: Yes! And I even know in a personal way how hard it was to make that show — it was no small feat. But the current shifts in representation is part of why I’m so excited about this moment in time. I mean we’re in a totally apocalyptic moment but how we cross the apocalypse is a huge question for me and I’m buoyed and inspired by what the thinkers I admire have to say about this, especially Indigenous, Black, and decolonial thinkers, who really understand that the predicament we’re in is very much a result of Western settler colonial culture, and the capitalism it fuels, and who are deeply connected to other ways of living.

I’m not trying to paint this moment as easy, but one of my greatest sources of joy and hope is to see someone like you. Seeing younger generations makes me feel like what the queer community was doing in my teens and 20’s mattered even when we were just trying to survive. And I can say to the older generations of queer people that I’m humbled and grateful for their vision, resilience, and all they did for liberation. I had it way easier because of them. It makes me emotional. I was listening to Ursula K. Le Guin today — the introduction to one of the Earthsea books which saved my life when I was young. She was talking about how you tell the story of imaginary worlds. There’s a way that she talks about it that reminds me of how we talk about our history. How we tell the story of queer and trans histories — what kind of story we tell — is really important. We’re seeing liberation now that is the fruit of many decades of efforts and some phenomenal young activists rising to the challenge. And it’s going to continue to unfold. That’s what I’m excited about.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that I like that I’m a tiny little piece in that legacy. We were so genuine and maybe, looking back, we seemed naive but we were dreaming up these possible worlds. And it’s happening now! I couldn’t have imagined back then that people would get on board with they/them pronouns or other pronouns we were experimenting with in the late 90s. We were playing around with gender and language for so long. I say playing because there was such a creative force behind it but it was also really serious — we were inventing new ways of being so we could exist.

So when I got the job on The L Word I was excited about the possibility of telling our stories. I thought my character could be the story that would represent queer outsider people. And once I realized it was going to be a trans story — which wasn’t something I knew when I first got the job — I thought we’d get to show a thriving, amazing person and community and a lot of what I had been experiencing for fifteen years. But that wasn’t the case. And I’m just an actor. I didn’t have control over the storyline. At first it was just cool to have a job! All my friends were blown away, like “what you’re on TV?? This is crazy!” But then I started to have misgivings “they’re going to tell it like this? Why are they doing that?”

Drew: Wait so when you were auditioning they didn’t say that it was going to be a trans story?

Daniel: They hinted at it, but I didn’t know that it was going to be a trans role or that they would tell that whole story. It was all very vague. When Ilene Chaiken told me a few episodes in, I remember thinking “oh shit, I don’t know if I want to take hormones, and I wonder, if they go down that road, if there’s going to be backlash against me.” And then I had to make this choice in sharing how I identified once the publicity started. I’d been identifying as trans for a few years, in the sense that I transitioned across the spectrum of gender and I could go any which way I wanted — what we call non-binary now. But at that moment in time, the word trans was really important for all my friends who were medically transitioning and identifying within the binary. I didn’t want to co-opt a word that was relatively new still and being so strategically used. So I was unsure how to identify myself publicly. I said I was queer, but I wasn’t sure how to explain the gender aspect of it. And, of course, people were asking all about it. Are you getting “the surgery”? Are you taking hormones? Most interviewers, most managers, everybody, did all the most transphobic things you can think of. But frankly having to explain yourself is nothing new to us queer and trans folks. I’m sure you can relate. We are always being asked to explain ourselves.

It was worth it to me because I was hopeful that I could bring a queer element into the show. I tried by having posters from The Gossip and Antony and the Johnsons on the wall of Max’s room, to try to make it less mainstream queer. The set designer let me decorate Max’s room. I went to a thrift store with my girlfriend Bitch at the time and we got a bunch of stuff, and early in the morning we set up the whole room. I was very invested in trying to make him like the people that I knew and like myself. But in terms of when I tried to make interventions regarding the storyline itself and unrealistic situations like Max getting rageful when starting to take hormones, I wasn’t able to affect any changes. That’s how it goes when you’re an actor rather than a writer or director.

Daniel in Frontiers Magazine. Photo by Aaron Cobbett.

Drew: The L Word has continued to be this sort of foundational text for certain lesbian-adjacent queer spaces. It’s something we talk about a lot and analyze a lot and think about a lot.

Daniel: Yeah!

Drew: I actually didn’t watch the show until I came out in 2017. And people warned me that it was really transphobic and told me not to watch it, but I did anyway. And I was actually surprised by the semblance of truth in its trans storylines along with all the bad stuff. One aspect of that is some of the early stuff with Max. I really like the dynamic around class like in the episode where Max goes with the women to a fancy restaurant. There’s a self-awareness around the cattiness that really works. And I love everything between Max and Billie with Alan Cumming. Your scenes together are really tender and I think those sex scenes are fantastic. When you talk about wanting to interject a certain type of queerness into the show, I feel like that happened there. I don’t know who was responsible for what but those early episodes really had some of that.

Daniel: That’s really great to hear. If we’re thinking about the lesbians who were making the show, they could probably relate to those scenes. But once Max began medically transitioning, I think they objectified him more. I definitely brought my own clothes though. I was like, I’m not wearing that designer stuff, I’ll wear this stuff.

Drew: The clothes that Max wears were your clothes?

Daniel: In the beginning, yes. I got the job and they said they were picking me up the next day so I stayed up all night compiling outfits with my girlfriend. We really wanted to make sure this character felt real. I thought the outfits would just be examples, but we ended up using a fair amount of them. The costume designer Cynthia Summers was amazing. She really respected that I knew what I was talking about.

Not that it was just the costumes. I knew Alan because he’s queer and from the downtown scene in New York. We were able to rehearse and choreograph the sex scenes. We proposed what we came up with to Frank Pierson who was directing that episode. He was open to our input because we said we wanted to make sure it felt real. And the tenderness between us was authentic because of that queer connection we share.

The show was a great opportunity, but I’m a multi-disciplinary artist. I’m a musician, I write poetry, I make culture, I’m politically active, I do performance interventions. Acting is one of many things I’m into. I remember some of the actresses on the show said that my life would not be the same after being cast and that it would live with me for the rest of my life. I didn’t really get that at the time and the huge impact it has had on my life has been a blessing and a curse. I find it interesting because I didn’t write the story. I was just a trans non-binary person in my early 30s who got this cool job. As a poet, I get quite sentimental, so Max came to life for me. He was and is real to me, like somebody that I know and feel very connected to. And a part of me is on-screen through him.

Drew: As the show did start to go more toward medical transition, did you receive any of that backlash? What was the response from the trans people in your life who had medically transitioned?

Daniel: I actually was surprised that I did not. I was expecting it. And especially as I started wondering how far they were going to take Max’s transition. Initially I was only supposed to be on for eight episodes. They said they had to see how middle America responded to such a “crazy” story. I didn’t know what they were talking about. To me Max was so sweet and great. I thought people were going to love him. But you could tell the network thought people were going to find him repulsive. They were really freaked out and they didn’t know what to do with me or the character. Even in publicity, they would say things like: “We can only have women on the poster!” They would always femme me up and I’d have to battle with them, and really push back on things like wearing lipstick. “But it’s a women’s show!” they would say. It was very bizarre.

But in terms of my queer community, they were supportive, encouraging, and in some sense proud. Perhaps we had grown accustomed to expecting very little from the mainstream media. I think we were still at a point where any representation felt like a step forward, in the sense that it at least acknowledged we exist. That’s a whole debate in and of itself: is bad representation better than no representation? And the bar was so low for trans representation. I mean, this was such a major step even if it also was hugely problematic.

Drew: Absolutely.

Daniel: I wouldn’t say people didn’t take it seriously, but most of my friends didn’t even really watch TV. I mean, some of them started watching because I was on. I pretty quickly realized that I had to just do the best job I could do. I was the one they chose and if the beards looked ridiculous or this or that I had to believe it was going to push the story forward in some way. That sounds idealistic but I really thought that.

At a certain point, Max’s story shifted in a direction that began to feel really sad to me: to leave Max pregnant and abandoned and never to have the resolution, comfort, and joy that could have been. Especially the scene where Max was dressed up to be Willy Wonka. That was really tough for me. And in terms of representing his particular gender affirmation process, I didn’t think it was necessary to make it go so fast and sensationalize it.

Drew: People wish it happened that quickly! Can you imagine if you started on hormones and then two weeks later you had a whole beard?

Daniel: But I also thought it was a soap opera! I didn’t have high expectations. If you’re a trans actor you’re going to take the role that you get offered unless it’s totally deplorable. There just aren’t that many roles to choose from, certainly not at that time.

And I don’t think it was inappropriate that I did the role. Part of the reason they wanted me was because I have a natural beard that I’d been wearing for years. I’d literally been beaten up multiple times and been afraid for my life for having a beard and being visibly non-binary. I’ve suffered a lot of abuse because of my gender. And I don’t think that’s what makes me trans. What makes me trans is magic and community and beauty. But it does mean I have a real, lived experience of transphobia and transphobic violence.

For me, the bigger issue was the whole sensationalized storyline.

Daniel in 2007. Photo by Cass Bird.

Drew: Yeah I mean that’s one of the one reasons I initially reached out to you. I felt like people wanted to have this very simple narrative of old L Word bad new L Word good. And they didn’t know your identity and were making all these assumptions in pursuit of this forced picture of linear progress. Our community has been having this discussion around casting for a long time. Just because it’s new to some people does not mean it’s new. And casting is just one aspect of representation. The writing is another huge aspect of it. There are all these other aspects of it.

The idea that you thought of it as a soap opera so most of the people in your life weren’t taking it that seriously is really interesting to me. Do you remember the first time you had a conversation with someone about the harm the show caused? Because I have people in my life who were coming out when The L Word was first airing and for some it was their first awareness of transness and that was really special in a good way. But I know other people who waited to go on hormones for several years because they were terrified of these things in the show that aren’t real.

Daniel: People generally have been kind. Generous really. Trans people who have taken hormones or transitioned in a binary way have mostly spoken to me in a really tender way. But I’m sure people were traumatized by it because I was. I had millions of people watching and I was in an unfriendly environment on set. I had to deal with that unfriendly environment in a very visible way and I know that it was harmful. But I think a lot of people are so empathetic they still identified with the character. As Ursula K. Le Guin says, we have to give credit to the reader for what their imagination brings to the story. As queer and trans folks, we’re typically very good at this. In the absence of seeing ourselves represented, we learn to read and view in ways where we can see ourselves and relate — most of us have learned to be really creative translators in that way. For a lot of people, Max was the first time they realized transitioning was possible and that’s really all I could’ve dreamed — to open a new possibility of being for people.

But in terms of people having problems with it, yes I’ve had those conversations too. Trans people who talk about how it harmed them and made life harder for them. I also really understand that.

Whenever I’d come to the writers with issues they’d say: Well, we’re telling a story and we have to do the arc and the arc has to match with all the other arcs. It’s drama and it’s not about real life or about being realistic. And I frankly didn’t feel like I had much agency in that whole world. I felt very vulnerable. I dealt with a lot of transphobia. From agents to managers to interviewers, I was faced with very invasive questions: Am I going to get surgery? How do I identify? Why do I have facial hair? Do I take hormones? And on and on and on. Viewers were, and perhaps continue to be, harmed by that storyline, and I had my own harmful experience with it. So there is a different yet shared experience of harm there. But I try to keep it positive, because really I want young people to feel the promise of this moment and to know that my friends and I from back in the 90s would’ve dreamed of this moment — to recognize that this representation that was harmful in some ways was also a watershed moment. I think it’s both/and, and that we need to make space for these kinds of complexities in queer and trans culture.

Drew: Totally. I mean something that I really appreciated about Disclosure is the way in which it held these complicated things next to each other. Pretty much everything they show has one person saying how meaningful it was to them and one person saying how traumatizing it was for them. And I think that’s such an essential part of experiencing on-screen representation as a person with a marginalized identity. And of doing that work. The choices were not to have a Showtime show that is representative of your community where you have creative control and get to spread your vision of queerness. The choice was The L Word or nothing. And you even mentioned earlier that you’re now aware of the show’s positive impact and its importance in the landscape of television and media.

I don’t perceive any of what you’re saying as negative. I think the honest experience of trying to make this work and trying to make a better world is messy and painful. I’m similar to you in that I sometimes try to downplay it for myself. I’ve had industry jobs that were challenging in certain ways where I dealt with transphobia and I don’t talk about it that much. Most of those experiences I still view as positive or I focus on the positive or I try and see the ways it advanced my career. And I think there are people in my life who hired me or who I worked with who would be heartbroken to hear me say that but the reality is it’s just complicated. I actually had one boss who took me out for drinks after we wrapped and asked to hear the honest truth of what the experience was like for me. I really appreciated that. But I’ve had to learn a certain level of self-respect. I’ve had to reprogram the ways in which we’re told a certain quality of treatment is acceptable.

Daniel: Yes.

Drew: So often I’m like well that person didn’t mean to be that way or it wasn’t coming from a malicious place. But those microaggressions or whatever you want to call them are really an added burden that those of us who are trying to change the industry have to work through. When I hear you talk about that I find it inspiring, because it shows that we can get through these things and actually end up with something that is imperfect but has a real impact. I mean, that’s why I do so much of the work I do at Autostraddle. I want to still revisit The L Word, I want to revisit Andy Warhol movies, these things that included us. They may be imperfect but we were there and you see that spark and that’s so special to me. I really care about our history and that’s part of our history.

Daniel: That’s really well said. And I was having to navigate through a lot without a lot of reference — I didn’t understand the world of Hollywood. But luckily I had Pam Grier. She was always very supportive of me in terms of dealing with the social dynamics and talking about the importance of the role itself. She was really amazing. She said don’t let anyone get in the way of telling this story because this story is very important to have on screen.

It sounds naive and idealistic but while I was facing some pretty extreme transphobia — not just in the story but in the work experience — I thought “just keep showing up and do the best you can do because this is more important than all that.” Because there were times when I thought about leaving. But I didn’t want the people who didn’t have the best will for me to silence the story. I just tried to keep showing up the best I could in the circumstances.

Drew: I think it’s really lovely and interesting that Pam Grier provided that support for you. So many of her most iconic roles were written and directed by white guys. And those movies are iconic and important and she’s incredible in them but they’re also filled with stuff that I’m sure she felt complicated about. So it’s interesting to see that sort of lineage of on-screen representation play out behind the scenes. If anyone knew about doing things that were compromises it’s Pam Grier.

Daniel: When I first arrived in Vancouver where we shot the show, she took me to see her horses. It was a very meaningful moment for me. I was very disoriented and she said something in the vein of don’t let anybody faze you. I’m here for you and you’ve got to tell this story. It’s really important to continue. I think she was forewarning me about that whole world because she saw how green I was. She was very kind and wise. I held her words with me when things were difficult.

Drew: The first time I saw a positive representation of a trans character was Pam Grier playing a trans woman in John Carpenter’s Escape from LA. She’s really cool in it and is a hero and it was so different from Psycho and Silence of the Lambs and this other representation I was seeing. And again going into the complexity of things it’s like yeah obviously I want trans actors to play trans characters but Pam Grier playing a really cool trans woman in Escape from LA? I was obsessed with that movie! And I didn’t know why because I didn’t know I was trans but I was obsessed with that movie. It’s such a tiny blip in the history of trans representation but it meant a lot to me.

Daniel: Yeah I was thinking about this movie Victor/Victoria. My mom kept me out of school one day as a surprise when that movie came out. She said we’re going to go see a movie sweetheart. It’s about a woman who plays a man who plays a woman. It’s Julie Andrews for Christ’s sake! It really moved me deeply seeing that at 7 or 8 years old. We learn to fill in the gaps somehow when we are so starved of representation.

I am definitely with you that trans actors should play trans characters. And maybe someone else should’ve played Max. I don’t really know. But I also had a lot of understanding of what Max was going through and could relate with a lot about his character even if my trans identity doesn’t exactly line up with his. He was introduced before he medically transitioned. Would it have been more ethical to have a trans man who was in the middle of that process be totally objectified? They should’ve just had a character who had already transitioned. So again, I think having trans actors play trans roles is vital but there is also the perhaps bigger question of the types of roles being written and how they are filmed.

Drew: Yeah I mean I take no issue with your casting because the story they were telling isn’t one that’s based in reality. They could’ve cast someone who had medically transitioned and then made them up to look pre-medical transition in those early episodes. But Max never gets top surgery! So they were too confused about the character and the character’s gender and his relationship to his body and the experience of most transmasculine people. Who they should’ve cast instead is the least of my concerns here.

Daniel: I didn’t even realize the joke was on me, because I just kept being so earnest like oh my God how cool he’s going to be pregnant! He’s going to have a baby! That’s so cool! He will have a bountiful life! Then all of a sudden they have him dressed up like Willy Wonka and everyone’s making fun of him. It felt extremely confusing and awful. I didn’t expect it to go this way. I kept being hopeful. I was still naïve about that world.

And I think there was a unique difficulty being what we now call non-binary. Gender expansive works better for me and that was what I tried to describe when I was interviewed by TV Guide in 2006. They asked how I identified and I said I live on a spectrum of gender. I wanted to leave room for the person from a small town who might use the word lesbian because that’s all they know. I just felt like it was a lot on one character because the show didn’t have any butch representation and a lot of people identified Max that way. But then he was supposed to portray this transmasculine experience. I wanted to leave room for people to project whatever they needed in order to see themself reflected. But nobody knew what I was talking about when I tried to explain my relation to the spectrum, the expansiveness, of gender.

TV Guide was like what? And then AfterEllen wrote up a quote that was put on my Wikipedia — and is still there! — and that’s what all the journalists based their articles on in recent years. I wasn’t as clear as I could have been in that quote but what I was getting at was acknowledging my political connection to lesbian culture and activism in terms of being critical of heteropatriarchy while also distancing myself from a cis binary view of gender. I was trying to place myself as both expansive in my own gender and in my sexuality in terms of not categorizing desire in a definitive or binary way. But unfortunately that intention didn’t get through and the quote was interpreted as me identifying as a cis lesbian or bisexual woman. Whereas again, to be extra clear after having painfully learned what happens when I’m not: I identify as trans and non-binary.

Daniel during quarantine playing a cover of Brontez Purnell’s “The Reason Why I Can’t Fucking Stand You.”

Drew: Do you want to talk a little about the experience of being misgendered in the press when Gen Q came out? There were all these articles saying the original L Word had a cis woman playing this trans man and now we have trans men playing trans men and everything’s good now. And first of all the trans representation on the new L Word has a long way to go. Just because you cast trans men does not mean you’re writing parts deserving of their talents. And also you’re not cis and there was no indication of that. When did that narrative start?

Daniel: It’s a convergence of different things. I think one major factor was that I was disengaged from social media for my own mental health and other people wrote my Wikipedia. I noticed in 2010 that it said that I was a cisgender lesbian and I tried to rectify that a bunch of times. But I was unsuccessful and then I just disengaged. I just felt so overwhelmed by the online world. And I felt private and just kind of like, well, that’s just Wikipedia. It’s not me. I didn’t realize until many years later that journalists use Wikipedia as a verified source and wouldn’t reach out to me to ask about my identity or experience.

When I opened that first article in Wired Magazine and it said that the problem with TV is cis people playing trans roles and Daniela Sea is a perfect example of this, it really hurt. I had this overwhelming feeling of being shamed that went back to childhood experiences of being so misunderstood. So I didn’t take care of it right away. I went into a very painful private spin and couldn’t address the misgendering publicly at the time. That’s part of how shame works — it makes you want to pull away and hide, and, as the queer and trans communities know all too well, it takes a lot to overcome that and be public about your truth.

Luckily a lot of people saw that article misgendering me and they were really nice to me about it. Some people I’ve known for a long time, people all along the gender spectrum, were really mad and upset and even wrote to the editors and writers to get them to retract it. I tried to write a statement clarifying my gender and my relationship to The L Word but it was just too overwhelming. But then more articles came out and I knew I should’ve made that statement. I ended up reaching out to the writers of the articles and the writer for the LA Times and New York Times was quite receptive and somewhat apologetic. My mistake was that I didn’t take care of my narrative in the online realm. And it’s important to do that — to say I’m this and make it really clear to the public. I don’t have a publicist or anyone who curates my online or media representation, and I was naïve about the importance of me tending to it. So to take this as another opportunity to be really clear: I identify as trans, and more specifically as non-binary and gender expansive. And I also identify as queer.

Drew: I struggle with this as someone who writes about media. I’ve been trying to figure out the language to use because it is important that trans actors play trans characters and sometimes you get into these conversations where people are like well you don’t know how that person identifies. And it’s like yeah but Eddie Redmayne probably isn’t a closeted trans woman.

But again casting is just one aspect of it. I can feel when a cis actor is playing a trans character. I feel it and I know that it’s not authentic. But usually if that casting choice has been made there are other problems at play as well. And as the conversation is shifting and more and more it’s not okay for cis actors to play trans characters I think a lot of people are acting like we fixed it when the reality is there are all these trans actors that are so incredibly talented who aren’t getting the work that they deserve. They’re getting characters based in stereotypes. They’re getting characters who are flat and boring. And I also think it’s important to leave room for some complexity in the discussion. Like have you watched the show P-Valley on Starz?

Daniel: No. Should I?

Drew: Yeah! It’s incredible. And there’s a character who is genderqueer and is played by a cis gay man. I think of that character as a trans character but it doesn’t bother me that they’re played by a cis actor. There’s sort of a blurred line there. It’s not the same as a cis straight actor playing a non-binary character because the show thinks non-binary people are just women who use they/them pronouns. This is a queer actor who may not use the same label as the character but is in the community and is portraying the character in a way that feels like it’s a part of him.

I just think about the communities I’m a part of and labels are so fluid and labels are so flexible. Creating strict boundaries around these labels is a misunderstanding of our history. And that’s not to say it’s not important to respect the labels someone gives themself or that different queer people don’t have different experiences. But the fluidity of these labels is important. It’s harder to write about and harder to talk about especially with a cis straight audience, but I think it’s important to present the complexity. If people are confused they can keep reading and learn more. I’m tired of oversimplifying it. I want to push toward a complete reimagination of gender and sexuality and a complete reimagination of society.

Daniel: The goal is liberation. For me it’s always been about full-on liberation. We’re talking about medicine for everyone, food for everyone, housing for everyone, anti-racist action — all of that has always been linked to me with what it means to be queer. And when I tried to simplify it in the mainstream it felt too vague. Western culture is caught in a Eurocentric and compulsory binary — an exclusive paradigm of either/or that you have to abide to or else. We’re talking about a worldview that has dominated the world through colonialism. As queer and trans people, we’re not inventing a world beyond the binary — we’re trying to go back to or go forward to possibilities that are our true nature, which includes binary gender for those for whom that works but also includes a lot of other possibilities.

Daniel, present day.

Drew: Can you share some of what you’ve been up to since The L Word ended? What’s your creative life looked like since then?

Daniel: Well I’ve always played music and I’ve continued with that. I’ve also traveled a lot, like to Peru and Brazil. At the same time, the last few years I’ve been really thinking about myself being a white settler and doing whatever unlearning I need to do regarding this. I can’t claim anything around that other than trying to understand where I come from and the position I’m in. I was part of a theatre performance art piece with my partner Marissa Lôbo and Jota Mombaça. I played a character named the white savior who’s this really hip, in-the-know, politically engaged queer and you start to see the greed underneath that and the ways the character is trying to own Indigenous knowledges under the guise of decolonial theory. I’ve been doing a lot of engaging with theoretical texts and working with these themes in art works and also attempting to integrate them into my life. Right now my partner and I are making an anti-racist television show for kids here in Vienna, that’s based in empathy and throws back to a certain kind of psychedelic 70s shows that I grew up with. I think it’s important to see kids as whole beings, thinking beings, that have a lot to consider as they learn. I’m also in a band called FEMMEdaddy with Edamwen Elijah-Roxane Osakwe and we’re recording an EP right now that should be released this year.

Acting is something I am putting my focus back onto as well. Opportunities are opening up for playing roles that are complex, riveting, and fun! I feel there are more and more parts for trans and non-binary people being written now and like it would be a different experience for me than what I had to face back in the 2000’s in the world of film and TV. It’s taken me some years to navigate the effects of the transphobia I experienced at that time. I’m looking forward to acting in more projects and hopefully having a corrective experience that allows for better work. That seems more possible now.

Drew: Yes. Absolutely. It feels like the mainstream is slowly catching up to where you and your community were decades ago. And that’s partially because of you. I know you don’t like to be the center of attention but those things we talked about as painful but essential stepping stones have led to the world we’re in now. And it is better. Or it’s at least more visible.

Daniel: For me it’s always been a collective effort even in the art I’ve made. It’s just how I like to live, create, and relate as a person who wants a system other than capitalism. But when we’re talking about vanguard culture pulling mainstream culture forward, what I want to mention and what is always in my heart is the cost. It’s fun to think about these pasts but we lost and we still lose a lot of people along the way. When I think about the 90s, I think about AIDS and our friends dying. And that’s only one part of the loss. We were willing to offer our whole future to step outside of society and we really risked a lot attempting to live out these queer possibilities of being. We were on the margins and we thought that’s where we wanted to be, but when I think back, it’s that there just wasn’t so much space for us.

We were so brazenly defiant. We’re going to do it like this. We don’t care what you think. And there was so much joy and humor in that, but we did lose quite a few people and I think about those people often. We lost people to overdoses, suicide, systemic violence, health issues due to lack of health care and health insurance. And those things continue to happen. I lose people to suicide almost every other year — it’s not something that’s over. So as we celebrate all the gains in visibility and liberation for some of the queer, trans, LGBTQIA2S+ communities at this time, I am also remembering those we have lost and continue to lose to oppressive, transphobic, racist, misogynist forces that do not want us to exist. It’s important to celebrate alternative culture and advances but not to glamorize it or get lured into thinking we’re post anything.

And yet I’m encouraged. I’m encouraged by all the beautiful art and writing I see happening. I’m encouraged by the younger generations and the older generations as we all keep revolutionizing ourselves. That’s something I’ve always loved about Angela Davis — she’s always learning and growing. She’s been an example of that for me since I first saw her speak as a teenager. She’s listening to younger voices and is continually evolving. We don’t want to get frozen in time. There are so many possibilities. And when I think of an abolitionist future and how society could be, I’m encouraged by the changes we’ve seen with queerness. It makes me hopeful that if you think of something that seems impossible, just a crazy idea or a way of living and you follow your heart to build it with your friends, it can become a reality. It’s possible to abolish prisons. It’s possible to have community gardens all through the city. Even in apocalyptic times we can still push for these things. That’s what has always driven me: true liberation. How can we be free and make sure that everyone is free?

Drew: I share a lot of your ideals and values and yet I’ve always been very invested in film and television. And the industry, as we’ve discussed, is not set up to be progressive. I’m always trying to investigate how to pursue these goals that are seemingly so contradictory with my values. And yet there’s a stubbornness or a hope — maybe a foolish hope — that those values can be applied to the world of mainstream film and television even if it’s not a particularly hospitable environment.

Daniel: Yeah but it’s changing. Hegemonic structures of power are always going to make it hard to bring those elements in but there’s just so much more stuff being made now. TV and film are much more decentralized now than when The L Word was on the air, which opens up more space for different kinds of stories to be told in different ways.

Drew: Absolutely.

Daniel: I’m pretty jazzed about the great writing and acting happening. So I think it’s fantastic that this is a focus of yours. I saw you were writing a script. I’m excited about what you’re going to make!

Drew: Thank you!

Daniel: It’s funny because I don’t know how much longer the world is going to exist in a way that humans can live on. And yet I’m still excited about all the TV shows! It’s the same thought in my mind. I don’t think they’re opposites. It’s happening at the same time.

This was effing amazing! Thank you Drew and Daniela. OMG. So grateful to have read this conversation from both your brilliant minds ❤️

I revisit this interview often and I get more and more out of it every time. Daniela is correct in stating that they created a wonderful, kind, easy to root for character in Max, and it’s always infuriated me when people have tried to flatten any issues with his storyline somehow with Daniela’s portrayal? I’m so glad they’ve gotten this space to share all of their incredible experiences and perspective. Thank you both for all of your insights

I’m so grateful for this interview. It’s astounding (and disheartening) to think about how many conversations about trans representation on The L Word and Gen Q have happened without Daniela Sea and I’m so glad they got to speak to you, Drew.

Wow, this is such an amazing interview. Thank you Drew and Daniela! I’m a transmasculine person who has only seen bits and pieces of the L Word for various reasons but honestly, this piece might be what leads me to give it another shot.

I am SO happy to read this. Thank you, Drew and Daniela.

This is an amazing conversation – thank you so much for sharing this!!!!!!!!!!

This is such a great interview. I’m glad to know more about Daniela. Drew, thanks for being a generous interviewer.

What a thoughtful and welcome interview. Thanks for this, Drew!

Amazing interview. Thank you, Drew and Daniela!

This is a really great thorough interview/conversation. Beautifully in-depth and I appreciate that you both hold space for flawed representations still having value and that it’s not that helpful to always be, well, binary about it (this is good/this is bad/etc).

Thank you for sharing, both of you! I don’t know what to say, but there’s lots to think about here.

this is one of my favorite things i have ever read on this website

Thank you for this fantastic, smart, heartfelt conversation! I always identified with Max, but felt a little ashamed when all the discourse around him was negative. Thank you Daniela for being real, for pouring yourself into this character — I saw him and now I know that I saw you and it helped me find myself: trans, nonbinary, gender expansive. So much love, so much gratitude for your work. <3

What a great interview. It was really nice to get to know more about Daniela.

Thank you both so much for sharing this conversation with us!

this is the best content I’ve seen on this seen, and one of the best interviews I’ve read in decades. Thank you for this. Have always appreciated Daniela Sea.

Wow!! This was so good and tender! Thank you to you both for this.

Thanks Drew, this was a wonderful interview.

I have always felt a connection to Daniela since first watching The L Word and it took me years to even try and articulate it. Drew’s comment that Max was played with “an authenticity and a level of truth” hit the nail on the head. This interview was so beautifully nuanced – thank you for sharing it with us

Agreed!!! For me, Daniela’s portrayal of Max always shone through whatever crappy storyline the show was putting the character through — there is a honesty and groundedness that Daniela brings to the character, and I’m so glad to learn more about Daniela’s life, background, and passions and to see how those informed the parts of Max that drew me in.

I agree. Max was one of my favourite characters and I related so much to him (whaddya know, I’m transmasc) and this was such an incredible piece. I didn’t want this conversation to end!

I love this! What a nuanced, thoughtful conversation. Thank you for sharing it with us.

This was such a great read. Thank you Drew (and Daniela)!

Fantastic interview, thank you so much to both of you!

This was so wonderful to read. Now I understand why I felt so connected to Max even tho the show clearly wanted me to dislike him at times! Thank you Daniela so much for your work for the queer community, including this very personal and beautiful interview.

what an incredible and moving interview, thank you Daniela and Drew

What a beautiful conversation! Thank you both for taking the time to unpack so many complex issues; this really resonated with some of my thoughts on Max as a character and trans representation more broadly.

Loved this interview!

Also love the knowledge that Pam Grier was supportive, it really makes me think those occasional little scenes between Max and Kit (when this won’t have been the most obvious combo to the writing staff) were probably driven by their off-screen friendship.

Thank you for this interview! Daniela’s performance always felt the most earnest on the show, in spite of all the negative storylines and comments. It’s great to hear you open up and share your passion for liberation and all that it can encompass

Drew and Daniela, thank you so much for this! I have wanted to know Daniela’s take on the show and their experience for literal years. I appreciate it so much, thank you!! Sending love to Daniela – sounds like the show and the Discourse around it since has been an intense and sometimes very hard experience. Am so keen to check out more of their work now.

Same.. I feel like this is the interview I’ve been waiting 10+ years for, since my first L Word viewing.

Thank you both, Drew and Daniela for this amazing interview. It makes me wonder what The L Word could have been if Daniela and and other lesbian, bi, queer, trans and non-binary actors had been encouraged to provide input into the development of characters portrayed on the show.

Wow this is a great interviewing. Thank you to both.

Wow!

This comment has been removed as it is in violation of Autostraddle’s Comment Policy. Repeat or egregious offenders will be banned.

You people really are fond of banning people who don’t agree with your views, aren’t you? Even if they are just as valid as yours.

Excuse my honesty.

Cee you next Tuesdays.

Thank you Drew and Daniela for such a thoughtful interview. Daniela’s comment on the writers’ focus on story arcs really explained what I felt was a broader problem with the show. There was this focus on telling certain stories without much care for the characters or authenticity. It was frequently frustrating and infuriating, and all the more so when the stakes were so much higher because there was no other trans, non-binary, or even butch representation. It is great to read a piece that recognizes all of the harm and also all the difficulties at that time of even getting a show full of cis white wealthy (or wealthy enough) thin lesbians made and televised.

Thank you so much for sharing this interview! It was amazing to read. <3

Love this interview. I was so drawn to all of Daniela’s acting work I could get my hands on in the early 2000s and I couldn’t articulate what exactly it was that drew me. Now I realize it was because Daniela was the first glimpse of queerness, not just LGBT, but true queer identity, that I was able to see as a small town teen/young adult. I so appreciate getting to see that, and getting to witness this authentic and thoughtful conversation here.

This is SO great. Thank you for creating this space and this conversation. Was fascinating to read Daniela’s story in conjunction with Drew’s thoughts. Thank you.

@Drew @Daniela – I reacted to L Word like you did Daniela, with disgust more or less. I watched the show only because of the lesbian man, and Max’ relationship with Alan Cummings’s character which was one of the earliest representations of a gay relationship between a cis and a trans man. I even bought the season only for those scenes.

I was traumatized by the whole pregnancy/Willy Wonka thing, I had blocked the memory until you mentioned in the interview- that ending was deeply offensive and unforgivable. It also reflected how cis lesbians saw trans men ca. 2005. I’ve seen that attitude many times in real life.

I liked the lobster conversation though– ;-)

This is a masterful interview/conversation. I have not been able to stop thinking about it since I read it two days ago!! Drew and Daniela, thank you so much for your honesty, self reflection, and vulnerability here. This is a really, really incredible piece of writing, and I know I’ll be returning to read it again. ❤️

Thanks so much for this conversation. I have massive respect for Daniela and just wish this could have been a less painful experience for them.

This.

This is huge, and brilliant. Thank you both. <3

This is the interview I have been wanting for the past decade. Thank you so so much for this!

Thank you so much for this nuanced and in depth conversation! I so appreciate getting to hear more about Daniela’s experience on the show and resonate so much with your experience of the queer community that is not well represented on The L Word.

This is fascinating! Thanks so much to you both, Drew & Daniela, for this thoughtful conversation! It really gets into a level of nuance that is so often lost in convos about representation (and the L word, let’s be honest!). I loved this.

Agree with all of these comments! This interview was direly needed and perfectly executed. Daniela and Drew are poets!

Ugh this website is always so great!

We deserve this greatness! Thank you!

Thank you so much for this interview. Seeing Daniela Sea on the L Word made such a massive impression on me, they were the first transmasculine person I’d seen on a mainstream show. The story was terrible, but seeing Daniela was important to me on my journey. I connected more with them than with anyone on the show, as a queer non-binary person. I’m sorry it was such a traumatic experience for them, and that their identity and experiences have been so erased. I found this interview deeply moving and hopeful.

Everything you said! <3

I’m…this is so good. Thank you, Drew and Daniela.

what a fantastic interview. thank you Drew and Daniela!

I just don’t understand this obsession people have with only trans actors playing trans roles. Acting is acting! You cast the actor based on the authenticity of the performance – not who they are in their personal lives.

The backlash against Scarlett Johansson cast as trans man in Rub and Tug was completely unnecessary. People were such bullies to her online that she ended up backing out.

I’m all for representation, and I do love authentic good queer content, but we really have to STOP the insults, the condescending remarks and the witty sarcasm when it comes to cis and straight actors playing LGBT roles.

Actors should be able to play whomever they want. Cis actors should play trans roles. Trans actors should play cis people. Non disabled people should play disabled people. Gay and lesbian actors should continue to play straight characters. Straight actors should continue to play gay characters.

It should be about the empathy that the actors feel. Not whether said actor has had a lived experience of the character.

I will check out again for more top-quality web content and additionally, recommend this website to all. Many thanks!

I don’t know how I missed this when it was published, but I’m so happy to have found it today. Great interview!

I owe my own coming out story to the L Word at least partially, but I always felt profoundly disturbed by the way they treated Daniel story. It is true that at least where I live at the time, the language for non-binary was not common or in the mainstream, but I still think the story could have been treated better.

Anyway, thank you very much to both of you because of this piece. It was a delight to read it.

Just discovered this via Drew and Daniel’s more recent AS interview and wow. Y’all are just wonderful. Thank you for having these conversations 🥹🥹🥹

I often watch this show, it’s really good and meaningful lesson. Playing duck life will help you experience life in the right way.

I watched The L Word when it originally aired, and ALWAYS understood Daniel to be trans & non-binary. I was actively engaged in queer anti-capitalist activism & reading queer theory, so maybe it was easier for me to recognize the language they were using around gender identity. I was immediately drawn to Max, and Daniel’s electrifying portrayal of his journey. This was 9 years before I finally actually came out as non-binary (because it finally felt like I could – that shit took time) but I recognized something unique, special & important in Daniel’s performance. I am so grateful for Daniel’s work as a creative person, activist & artist. Representation IS & was so important. Thanks to both of you for this much-needed conversation.

Also – I stopped watching The L Word before the pregnancy storyline. (I hit my wall at the Jenny TV show plot.) And, I didn’t like what the writers did with Max’s T-arc, even though I liked the scenes with the LEGEND that is Alan Cumming! Yet in spite of the writing, Daniel’s performance was so strong & sincere that I continued to have affection for Max.

Etumax prime Royal honey is an instant source of energy to enhance male vitality. Etumax Pure honey fortified with a selected mixture of rainforest herbs (Tongkat Ali and Ginseng) is Nutritious honey enriched with vital biomolecules in, Bee larvae Nowadays, most people suffer from stressful lifestyles with overexertion, and many face emotional conflicts.

Etumax Prime