So, honestly, I start out with the same feeling every single time after finishing these books, which is “I can’t talk about this.” And then I experience a second, corollary feeling which is “I don’t know how to talk about this without talking about me. I don’t want to talk about me.”

But I think this time I actually don’t know what else to do. I am literally incapable of talking about a memoir about a queer woman grappling with a fraught, distant, infuriating relationship with her father without talking about myself. See, the thing is, I read almost all of this book while my father was, in fact, visiting me! My father and I see each other 2-3 times a year, and there is always at least one other family member present to act as a buffer. But not this time. Also, since I now live alone instead of with a house full of roommates, he didn’t see any reason to stay in a hotel, and instead slept on an air mattress in my tiny one-bedroom apartment. So weirdly, but I guess appropriately, this book was the only companion I had. I read it in an armchair while he read his Bible (which he carried with him from ten hours away) on my couch, and I read it alone in my bedroom while I listened to my dad fumble with the kitchen light and the wine bottle in the other room. It was, I guess, a lot sadder because of that — because I couldn’t read it like it was a story, something outside myself. But it was comforting, for the same reasons.

It feels a little weird to call Fun Home a memoir. I guess I don’t know why I do — the books calls itself a “Family Tragicomic,” and you could definitely argue that it’s more a book about Bechdel’s father than Bechdel herself, which I guess is what a memoir would be. But even if you leave aside the gay — the fact that Bechdel discovers that her father has had affairs with men (and some of his male high school students) that coincides awfully with her own realization that she’s a lesbian — this is kind of a book about the way in which Bechdel’s own story and her father’s are inseparable, or at least how it would be difficult to tell the former without telling the latter.

There is something about being a tomboy, about the father-daughter relationship that grows out of that. If you are lucky enough to have a father. If you are lucky enough to have a relationship. Which Bechdel was, and which I was. Sort of. Maybe this isn’t everyone. But I remember the time when I was eleven years old, and a woman in the mall was trying to recruit girls passing by for some sort of ‘modeling program.’ She tried to hand me a card, and asked “Have you ever wanted to try modeling?” I said no. My dad was so proud, clapped me on the shoulder for being his little girl who didn’t care about being beautiful. Years later, when my brother wanted to get his ears pierced (I think he wanted big fake diamond earrings like a rapper’s, it was very on trend) my father said no, never; it wasn’t what boys did.

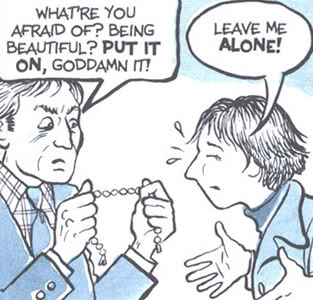

That’s not how it works for Bechdel and her father. He wants her in dresses; he wants her to look nice enough to be a credit to him, something beautiful that he made that he can be proud of. And he is proud of her, of her brain if not her outfits. “You’re the only one in that class worth teaching,” he says when she ends up as a student in his high school English class. And she says, “It’s the only class I have worth taking.” There’s something there, there’s something in there that only a reticent father and a moody teenage daughter can give to each other. Some kind of approval, reciprocal admiration. Something that we don’t actually get, I guess.

Bechdel’s father is dead. He dies, he died, when she was in college. Younger than I am now. He killed himself, or so the evidence would suggest. Which changes everything, which defines everything. Because Bechdel is left to imagine his life as it could have been, but maybe even more so to imagine his life as it was. Filling in the blanks. There are a lot of blanks. She has his letters, and we see them too, but those aren’t the whole story. If there’s one thing we learn in Fun Home, one thing that Bechdel herself knows even as she’s writing a book, it’s that the things we write are more about what we want to be true than what is. We write things for a lot of reasons but not necessarily because they’re true. When the only thing you really know about someone is that you don’t know the truth about them, how do you remember them?

It would be easy, in a lot of ways, for Bechdel to cast her father as a villain. He’s distant, he’s duplicitous; he’s angry. He hits her and her brothers, he throws things. He buys beers for minors to seduce them. He commits suicide and leaves no note. Maybe that’s the worst part of all. And she holds him accountable for that; there’s no denial of responsibility for the things he did, and the things he didn’t do. But she finds some responsibility for herself, though, too. Accurately or not, fairly or not. “If I had not felt compelled to share my little sexual discovery, perhaps the semi would have passed without incident four months later.” Because that’s the thing about dads, right? Somehow nothing that they do to us, or don’t do for us, is quite as bad as our refusing to forgive them for it. There’s a weird sense of contradiction throughout, one that is completely honest even when it seems insupportable: the lack of emotion that Bechdel is able to summon about her father, but her simultaneous preoccupation with him and the huge way in which his short life still informs and occupies her own. Bechdel talks about how grief can take the form of its absence; the sadness that builds up over the course of a life until it’s so big that it eclipses the sadness of death.

“It’s true that he didn’t kill himself until I was nearly twenty. But his absence resonated retroactively, echoing back through all the time I knew him. Maybe it was the converse of the way amputees feel pain in a missing limb. He really was there all those years, a flesh-and-blood presence steaming off the wallpaper, digging up the dogwoods, polishing the finials… smelling of sawdust and sweat and designer cologne. But I ached as if he were already gone.”

This week my dad picked up a framed photo off a shelf in my apartment. “Are these your friends in your [graduate] program?”

“No, Dad,” I said. “Those are my old roommates? I lived with them? Remember them? You’ve met them.”

“Oh,” he said. After my dad left, on a Monday morning, a friend of mine asked “Do you miss him?”

“No,” I said. “We’ve gotten along a lot better since we moved far apart.”

“I meant now,” my friend said. “Like, since he’s left.” The thought hadn’t even occurred to me. What was there to miss.

There’s a sense throughout that Bechdel is angry at her dad. The image of her sitting next to the phone, bored while her dad rhapsodizes over Joyce on the other end of the line. It’s so familiar, it’s a perfect image. (And a nice example of why this is so great as a graphic novel — when I close my eyes I still see cartoon-Alison in the fetal position on her dorm room floor as her mother tells her about her father’s secret, and the giant looping attempts at obscuring her own record of her life.) And why shouldn’t she be — he lied, to her and to her family, he embarrassed them in front of the entire community, and he alternated between distant and aggressively controlling, with only occasional instances of tenderness. How could you not be angry. And so she is, but you get the sense that’s not the core of it, that’s not really where the anger comes from.

Maybe more than anything else, the book is a study of a virtual stranger, a profile of someone who was always just out of reach, assembled from found objects and remembered evidence. Going through a box of old things, she discovers a photo of her father posing in a women’s bathing suit — there are no clues, no context, but he looks like maybe he’s enjoying it, like maybe he feels good. Years later, (presumably) without her father’s knowledge, Bechdel and her friend dress in his suits and ties to be pretend to be slick con men. Dirty Harry cool, James Bond aloof. “Putting on the formal shirt with its studs and cufflinks was a nearly mystical pleasure, like finding myself fluent in a language I’d never been taught,” she writes.

Bechdel’s dad died before she ever had a chance to know him, before he had a chance to know who she would grow into. That’s something to be angry about. Even if he had lived, he still wouldn’t have been present in the way she needed him to, wouldn’t have known her as deeply as he should. And no matter how long he lived, she would probably never have really known him. “We were close. But not close enough,” she says.

I hold my dad responsible for a lot of things that I find hard to forgive; some fairly run-of-the-mill, especially if you’ve ever been to divorce court, and a few that are less ordinary. He actively attends Tea Party meetings, believes that homosexuals should be prevented from having access to young children aka being Boy Scout leaders, and tried to convince me to break up with someone because the color of their skin as compared to mine was “dangerous.” We have a list of things we don’t talk about: politics, religion, the Middle East, almost every other member of our family. I can’t pretend I’m not angry. But I think the worst thing, the thing that I actually can’t forgive, is that we spent four days together and ran out of things to say to each other at the 1.5 mark. He left my apartment while I was at work, and he didn’t leave a note. I didn’t look for one when I got home. He’s not the only one with a questionable claim to forgiveness.

Thinking about how her desire, ambivalent as it may be, to “claim” her dead queer dad, Bechdel writes “Erotic truth’ is a rather sweeping concept.” Then she says “I shouldn’t pretend to know what my father’s was.” Every single time I read that line, it reaches me as “I shouldn’t pretend to know who my father was.” I guess that’s right, too.

That’s all I’ve got. Now it’s your turn.

rachel, thank you so much. this is an amazing article. i loved it and this book. i can definitely identify (although my father is alive, not queer, and still married to my mother) but we, too, have a lot on the “to forgive or not forgive” list.

Rachel, you make this book sound like the kind of aching read that we should have to hunt down, cry over, and lend to only our closest friends.

Almost exactly a year ago, I was loaned this book by an amazing girl who, after some complicated scary times and omgzfeelings~times and and “I don’t want to be in a relationship right now” times and awkwardness and ignoring each other and realizing that was stupid, has ended up being one of my closest friends. Even though I was just beginning to realize it at the time, I’d say your statement is pretty accurate.

thank you.

There is definitely something about it that feels deeply personal, and it is difficult to talk about it without bringing in my own life somehow. One part that really stuck out to me and broke my heart a little was when she was admitting that she doesn’t know for sure if his death had anything to do with her coming out at all, but she is reluctant to entertain that idea because that is the one bond she feels yet between her and her dad.

I used to feel a similar weird distance from my own dad, when I was in high school. We had nothing to say to each other; he’s very right-wing conservative, a little bit homophobic, and I was just figuring out that I was queer. I can relate to what you said about a bond between a lot of tomboys and their dads. Like, we can’t really communicate how we feel to each other, but he can help me practice soccer in the backyard and it feels like something, at least. I’m fortunate that our relationship has improved drastically since I moved out.

Alison’s dad reminds me a lot of my grandpa, who is gay. I didn’t know him really before he came out, but from stories that I’ve heard, his anger and obsession with outward appearance and perfection sound really similar. It’s almost like looking at what could have happened if he didn’t end up accepting who he was. That’s probably reading too far into it, but it’s just a thought I had.

See there, at first I tried to resist bringing up my own family while formulating a response, but then I was staring at the screen, not knowing what to write. Thanks for picking this book for us to read, I loved it.

You did a heartbreakingly amazing thing in writing this, Rachel — thank you for sharing. As with all of Bechdel’s works, I poured through this one in a couple of days, disciplining myself to make it last that long. I just…I have so many feelings but mostly they come down to some form of heavy thank you.

Your second last paragraph rings so true for me, Rachel. My dad and I are just starting to build a relationship. Up until I was about 19, I was “mommy’s girl”, my older sister was “daddy’s girl”. My parents were not close (I’m told that they began to drift apart after my sister came along. My birth was apparently the straw that broke the camel’s back).

After learning that my dad had been having affairs for nearly a decade when I was 16, I became closer to my mom than ever. She was a victim, my dad was a dumb loser. I swore that I’d never invite him to my wedding, good riddance.

It wasn’t until I began university that my image of my mom as this amazing woman began to fade–I developed an eating disorder, and she forbade me from seeing a therapist because she said it would make the family (ie. her) look bad. She actually told me my eating disorder was the result of my questioning of the religion I was brought up with, and that if I just went to church like I used to, God would take it all away.

A few years later, I was sexually assaulted by a man in broad daylight while on a walk in a nearby neighbourhood. When I got home, I told her what happened, and that I wanted her to take me to the police station so that I could report it. She told me that it was no big deal, that “that’s just how men are”, that I should be “flattered”, and that it “happens all the time”. My best friend took me the next morning, in heavy snow, to the police station. She didn’t mind being late to class.

My dad and I started making awkward attempts at bonding when my mom suddenly became my sister’s BFF after she (my sister) got knocked up. We were sniffing each other out, like two dogs. I guess we still are. I’m not ready to talk about his infidelity with him, but he knows about my issues with food, and that I’ve started seeing a therapist “secretly”. He always (sincerely) asks how my sessions are going, and asks whether I want him to come with me, because he feels that a lot of my issues are his “fault”.

I’m starting to see that he’s really not at all the awful person I grew up thinking he was. It’s hard to forgive him for screwing around on my mom, but after learning what my mom is really like, I…can’t condone what he did, but I can understand why he did it. I’m finding it harder to forgive myself for freezing him out for so long, for refusing to listen to his side of the story, and casting him as the villain.

And wow, I just made this response all about myself…

“And wow, I just made this response all about myself”

There is nothing wrong with that. Maybe you needed to say these things, I think you and Rachel are courageous to share it with us and both posts are beautiful. And AS again shows itself to be the safe kind of place people can do so.

I think it’s hard when you realize your parents are much more complicated than you used to think but it happens for most people. Don’t be angry with yourself for blocking him out. I have a really complicated relationship with my dad, too, and I blocked him out for about three years because of it. It was only after I came out and he accepted me when my mother was (and still is) very hesitant that I really bonded with him. He also had really terrible anger problems when I was younger that therapy has helped him overcome. I think the way we relate to our parents is sometimes situational–it takes a change in context and situation to help us realize our commonalities and the more gentle side to our parents. Anyway, that’s my take. Also, I make everything about myself. Sometimes it’s a good way to relate to people. It shows you have a lot of empathy, I think. :)

I love reading Alison Bechdel’s books and read and re-read fun home obsessively for two weeks( it went everywhere I did.) I love that you write about her books and I’m excited for the new book to come out and then your review :D

I love this graphic novel so much, I can’t express it in words. But you can so props.

Rachel, the ones where you talk about yourself are the best ones.

I feel like this book is much smarter than I am. And that has made it one of my favorite books.

I loved this when I read it a few years back. You guys should absolutely check out her graphic novel series ‘Dykes to Watch Out For’ as well!

this novel became incredibly relevant to my life.

my very first girlfriend gave it so me about a year after my dad came out to me and left my mom.

so many parallels.

Rachel I love this so much. Your father has always been this totally bizarre character to me and I was wondering if you would touch on that in the Fun Home post and I’m glad that you did.

i was originally going to just comment with “did y’all know that fun home is being made into a musical?” (which it is). but now i’ve read this, and i’ve been living with my parents for the past four months and trying to deal with deep scars in my relationship to my father, and this is all so close. i love it.

but the musical thing is still exciting.

You’re entirely right when you said it’s hard to separate this book from yourself. Maybe if we weren’t all young queer women, it would be different, but at this point i don’t see a way I could not identify with this it.

Alison’s father died when she was 19, almost 20, just as mine did. She grew up 2 hours away from me in Pennsylvania. We’re artists, although she is far more talented than I.

When I saw her speak, it was almost like a religious experience for me, and I probably put more weight on her visit than was healthy. After all she is only a person, and it’s unfair to expect more from someone than to be a human being. But Fun Home got under my skin in a way few books do.

What I took from it most was the sadness of not knowing her dad as an adult, good or bad. The older I get, the more pieces of the puzzle that was my dad I discover, but they have to be found under old furniture, instead of given to me by the man himself. What I do know is every day, I feel like i’m a little more like he was. Whether that will be my undoing, or my saving grace, has yet to be seen.

What a coincidence! I randomly decided to buy this book yesterday and literally just finished it five minutes ago. This article was a nice follow-up!

I got to read this book for a class when I was in college! It was awesome.

this was pretty amazing.

This was an excellent article, so beautifully written and thought-provoking. It really made me consider about my relationship with my dad. I hardly ever talk to him cause we have so little in common, when we do talk I default to sports since it’s one of the few things that we share.

Holy shit, Rachel!

This is awesome!

Really. I don’t know what else to say.

oh goodness thank you Alison! That means so much to me, I can’t even tell you.

eeeee ‘There is something about being a tomboy, about the father-daughter relationship that grows out of that’

when i read that early this morning i did that pre-crying shallow huffing thing and then i stopped but i’ve been thinking about it since then. i’m lucky my dad is pretty awesome.

you know how it’s so difficult to come up with a list of top 3 books of all time, this book is easily the one that goes on automatically. there are so many things that i love aside from the overall feeling which i guess is what everyone else is talking about; the literary references and allusions, the clear lines, the different shading styles, the watercolour, the non-linear narrative structure, the unspoken indescribable things that pictures reveal.

i’m looking forward to the next book so much.

This book was beautiful. So was your article, Rachel.

I have no words left, really. No words deep/smart enough to describe this book!

wow. truly great article. thanks rachel

I’m really glad you wrote about you, Rachel. Until I read your article I couldn’t pinpoint exactly why Fun Home had resonated with me so much. My relationship with my dad is way more like Bechdel’s one with her dad than I initially thought. The distance, the secrets, the anger and the difficulty of forgiveness all define my relationship with my dad.

Also, how awesome is it that Alison Bechdel commented on your article?

“I am literally incapable of talking about a memoir about a queer woman grappling with a fraught, distant, infuriating relationship with her father without talking about myself.”

Thank you. There are a lot of us out there, and none of us know the others exist.

I don’t know what it says about me that my first thought whilst reading your article was ‘I wonder what Bible he reads.’

My first gf gave this to me and I went to pull it off the shelf when I saw this post and then remembered I gave it to a homeless lady. “Somehow nothing that they do to us, or don’t do for us, is still not as bad as our refusing to forgive them for it.” So true. And I really enjoyed what you said about truth. But I think it’s more than just wanting something to be true. It’s writing from our own truths even when our truth, that of which is relatable and speaks honestly to our feelings or views, regarding someone or something totally negates someone else’s truth.

Something else I got from this novel was that lies people tell so that they don’t have to be vulnerable or because they’re too afraid of being vulnerable is what keeps people from relating to one another. Everyone is so afraid that they won’t be liked or loved or accepted that they build barriers. If we could all just say this is me, I am weak sometimes, I need help sometimes, I need love then everyone would realize were all up the same fucking creek paddleless and not have to feel so alone and isolated in FEELINGS.

My dad died about 8 months ago. He was hardly around growing up and two days before he died he said about five sentences to me and those five senteces that took him less than a minute to utter told me what kind of man he was inside but was just too afraid to show. I have more respect and love for him for the small moment of time then every other moment I had with him combined.

I’m getting carried away, I would still really like to know what Binle he had with him if you remember…

Oh, and thank you for caring and sharing.

‘Bechdel’s dad died before she ever had a chance to know him, before he had a chance to know who she would grow into. That’s something to be angry about. Even if he had lived, he still wouldn’t have been present in the way she needed him to, wouldn’t have known her as deeply as he should. And no matter how long he lived, she would probably never have really known him. “We were close. But not close enough,” she says.’

Aren’t all of those statements true about anyone whom we allow ourselves to love?

I loved this book, and your article Rachel. It all rings really true and your thoughts helped me make sense of a number of things. Forgiving my dad for some of the things he’s done is so hard, and sometimes I don’t even know what the point of forgiving him is. Most of the time I feel like I don’t even know him, but I should because he’s my dad. This basically sums everything up: “Somehow nothing that they do to us, or don’t do for us, is still not as bad as our refusing to forgive them for it.”. Thanks again for writing this…

As a publishing poet I am amazed by the raw content of Alison’s books. While art is about expression of emotion and ideas, it is (for me at least) also a way to add obscuring details on top of deep sentiments that the world often doesn’t want to deal with in a straightforward manner. That Alison is willing and able to express such straightforward ideas is humbling and impressive.

Rachel, just reading your review brought tears to my eyes. This book will be added to my library by the end of the day. I have a lot of the same issues with my father (I don’t call him dad for numerous reasons..), and even though the better part of me feels like he has never and will never be there in the way that I want him to be, another part of me is constantly wishing that he would just CALL, or just aknowledge my existance.

Even now, sitting here at work, reading your review, the only think I can think about is maybe trying to find my own dad and try to bridge that ever-present gap that was formed too long ago to remember.

Thank you, Rachel. For the review, and for pointing out that it’s not JUST ME who has these stupid father issues.

Thanks for the great read! (Yours; I’ve already read Fun Home)

“It was, I guess, a lot sadder because of that — because I couldn’t read it like it was a story, something outside myself. But it was comforting, for the same reasons.”

The first time I read this book, it got under my skin. I love Bechdel, but her account of obsessive self-editing and painfully acute self awareness was too much; it irritated me because it was me. How powerful that so many of us have read this as something inside of ourselves, and in so many different ways.

“When the only thing you really know about someone is that you don’t know the truth about them, how do you remember them?”

The second time I read it was pretty soon after my dad died, maybe even a week or so. This time it didn’t crawl under my skin so much as it ripped it open entirely. It felt great, actually, to read another account of someone filling in those holes, constructing a narrative that made enough sense to be a workable history (literally, in Bechdel’s case). Particularly since I was about to embark on that strange trip myself. Bechdel is the rare graphic novelist/cartoonist who is a writer first and an illustrator second, but no less powerful in either form.

I look forward to digging my copy out again to see what I come away with. It’s difficult every time — and that’s good.

Of course, this book made me look at my own relationship with my dad. I connect with some of the same issues – the distance and the anger. We’re able to connect perfectly in some ways, but more often I find our relationship to be incredibly frustrating.

“Our home was like an artists’ colony. We ate together, but were otherwise absorbed in our separate pursuits” (p. 134).

This is one of my favorite lines. There are times when a family really lives together interacting and experiencing things. There are other times when a people who make up a family revolve around one another – the interactions and experiences become routine and disingenuous. My family seems to have become that second-type, so it was consoling to see that illustrated. So yeah, I definitely loved this book.

Thank you for sharing your story. Every once in awhile an article i read touches me, but it is only because the writer is allowing others to see what they are really feeling.

Thank you, Rachel. My father is still alive, but I spent several years checking the obituaries every day when he was homeless, assuming that he was dead because I hadn’t heard from him.

He’s a bit more engaged in the world now, and I’m his best friend on the entire planet, but I’m still not out to him because he’s also very homophobic (which I figure is at least partly due to the fact that he was sexually abused) and also because I just don’t feel that’s he has earned my confidence or trust.

My relationship with him is so complex (and I still can’t decide if that’s better or worse than non-existent), I feel like usually the only way to deal with it is by joking about it or not discussing it. Thanks for discussing your situation here. It’s nice to know there are other people out there struggling with whether or not to share these stories.

Thank you too, Alison. This sounds like a book I really need to read.

Rachel, you write like an artist.

i think im gonna have to read this now, it sounds amazing, good but disturbing as all the best books are…

Rachel, this article is really amazing.

Just, thank you.

this is really perfect and it’s hard to talk about, so i want to just say that i love how you put this into perspective. thank you rachel xo

I found your tomboy comment really resonating, because my dad sort of takes both sides- your dad’s and Allisons’. He never let me cut my hair short as a kid because it was unfeminine, and made me wear the dresses my grandmother bought. On the other hand, he took my side against mom when I said I didn’t like dresses and makeup, and when I was 8 and he was trying to get back in shape he’d let me box with him, and we fixed fences together.

I read Fun Home, and it’s funny, because my relationship with my dad is almost a perfect contrast with Allison’s. Her dad was distant. Mine says he loves me often and earnestly. Her dad was feminine. Mine’s what happens when you combine a scottsman and a country boy. She picked up the pieces of who he was after he killed himself, trying to figure out why. I’m watching mine eat and smoke himself to death, knowing exactly how this ends. And yet, I connected so much with her story. So much of what she said felt like I was saying it.

‘The thought hadn’t even occurred to me. What was there to miss.’

I can relate.

I just now read this for the 3rd time.there will be a 4th and 5th …

I like what you do with words.

This is a wonderful article, and absolutely true to the spirit of Fun Home, I think, that the only way you’re able to talk about it is by relating it to yourself. I read it for the first time accidentally in a tiny bookstore in York, where I found it amidst pasteboard-bound old editions of plays from the 30’s, and promptly curled up in a corner on the floor and read the whole thing in one go. I read it again this year for my GLBT Lit class, and loved it even more.

One of the things I love about it, because I am a geek, is how intensely *literary* the storytelling is. Every page is full of allusions and connections; it’s incredibly rich, and really enjoyable to read because of that richness.