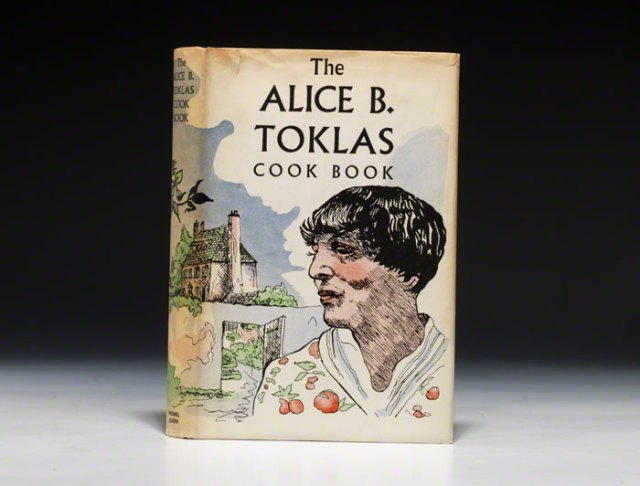

It’s easy to see an old cookbook as a piece of history, but it’s quite another thing to cook dinner from it. This year is the 60th anniversary of the publication of The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook, the patchwork of recipes and stories that chronicle the life through meals of Alice B. Toklas and her partner, writer Gertrude Stein. To celebrate, I decided to pull the book off the shelf — it is one of my favorites after all — and actually cook a few of the recipes. Although I adore the book, I’ve always held the capital “F” French food at arm’s length (Frog legs! How much heavy cream?!), which felt like a bit of a cop out. So, I finally got over my nerves and decided to cook with Alice.

Toklas wrote the cookbook following Stein’s death, after the repeated urging of Random House that she write her own memoir and allow them to publish it. She was ill at the time and — a type-A woman after my own heart — kept herself on a strict writing schedule while she was sick in bed to finish the book. As someone who cares a lot about food and writes about it professionally, I find it both funny and deeply moving that, when asked for a memoir, Toklas wrote a cookbook — a rambling love story told in lunches and Sunday dinners, in guests and the food and stories that came with them.

Structurally, the book has more in common with a community cookbook than most contemporary cookbooks or even food memoirs. It reflects the highs and lows of wartime and, as a result, combines high and low recipes in a way that is completely uncharacteristic of cookbooks being published today. It — oh, so refreshingly — lacks the sort of polish, and linear structure that we expect from contemporary cookbooks. Instead, its driving structure is Toklas and Stein’s life together.

A quick google will tell you that the most enduring recipe from the book, at least as far as the internet is concerned, is the pot brownies. Fair. Also, sort of a bummer because there are a ton of even weirder, cooler, and maybe even more worthy of consideration recipes in the book. I started with Oeufs Francis Picabia, which I’ll affectionately refer to as “Treat-yo-self Eggs.”

The recipe, given to Toklas by Picabia, a French avant-garde painter and poet, is basically next-level scrambled eggs. It starts innocently enough, by mixing 8 eggs in a bowl with a fork, but from there asks that you pour those eggs into a saucepan — yes, a saucepan, no, not a frying pan. The eggs are then cooked over “very, very low” heat for 30 minutes, over which period of time you stir them fastidiously with a fork and gradually add ½ pound of butter. For those of you playing along at home, that’s two standard size sticks of butter.

Toklas describes the transformation that happens over the course of this recipe as, “The eggs of course are not scrambled but with the butter, no substitute admitted, produce a suave consistency that perhaps only gourmets will appreciate.” Although I obediently set my phone timer for half an hour, my results were far from suave. It seemed like after a certain point the eggs couldn’t incorporate any more butter and I had eggs swimming in a lagoon of butter. Hence, treat-yo-self eggs.

Next up, I tried Custard Josephine Baker, which is more or less a boozy baked banana pudding. It’s a fairly standard baked custard, eggs, milk, sugar, a little flour (full disclosure: I’m gluten free, so had to substitute the very historically inaccurate gluten-free flour). What makes this custard fancy is kirsch and bananas. However, I scratched my head a bit as to why, in a book that is in no way adverse to culinary fats, this recipe wouldn’t include a bit of heavy cream, as I felt like most other custard recipes would. Was this “health food” custard? It smelled amazing while it baked, although I had to cook it for almost twice as long as the recipe indicated to get it to set up. The custard wept a bit, ie: it was watery, but this wasn’t a complete bust.

The biggest victory of this recipe for me was in the way it was written. It calls for “liqueur Raspail,” which Toklas later notes, “Raspail is a liqueur for which it will probably be necessary to substitute another.” Maybe this seems like a throwaway line, but in fact it stuck out to me as a favorite. It’s completely refreshing how contrary this is to the perception of recipes as rigorously tested and perfectly replicable experiences. This lovely bit of subjectivity also points to how much this recipe — and many others in the book — elevate the moment in which they’re made, the life around the recipe, and Toklas’ recollection of it.

I made Pork “Alla Pizzaiola” of Calabria, an entree that started with pork chops seared in butter that I wished had ended there. I may have misread the oddly worded narrative recipe and cooked the pork chops for an hour in a mixture of capers, anchovies, tomatoes, entirely too much parsley, and one “wineglass water.” Again, not bad, but not particularly revelatory either. It left me wanting to pan fry everything in butter, which I suppose could be considered a success.

My favorite thing that I cooked from the book is a bit improbable. I wanted to make the Salade Aphrodite because the recipe indicates that it is “ideal for poets with delicate digestions” and I happen to be a lady with an MFA in poetry who likes a good salad. There’s nothing especially noteworthy about the recipe, except for the element of speed built into the directions, which read, “The beauty of this salad depends entirely on how quickly the apples and celery are stirred into the bowl of yogourt. This prevents their becoming brown.” I love how this ups the stakes on what is a very simple salad, 3-ingredient salad if you don’t count the salt and pepper.

Beyond being crispy, fresh-tasting, and having a great balance between sweet and savory, I appreciated how this salad took things that most folks are likely to have lingering in their fridge and made something much greater than the sum of their parts. I’ve included my adaptation of the salad below, should you also decide that you’d like to cook with Alice, which I heartily endorse. The book is a powerful work of compilation and remembering and even if all of the recipes aren’t timeless, the story they help tell certainly is.

Salade Aphrodite

adapted from The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook

serves 4 as a side

4 stalks celery, finely chopped

1 1/3 cup greek yogurt

2 tart green apples, peeled and finely chopped

salt and pepper to taste

10-12 fresh mint leaves thinly sliced

1. In a medium bowl, combine the celery and greek yogurt. Stir to combine.

2. Peel, slice, and chop the apples one by one, stirring them into the celery and yogurt as you go to prevent browning.

3. Stir in the mint and season with salt and pepper to taste.

4. Serve immediately or refrigerate until ready to serve.

Note: Because I love how economical this little salad is, I hesitated adding the fresh mint, but I had some on hand and it’s a really nice addition. This is still a stand-up salad without it.

As someone with a long-standing fascination with power couple Getrude and Alice (to the point where my stage name is Alex B. Topless), it’s really neat to see someone try out the recipes from her infamous cookbook. I’m gonna bump the Diane Souhami bio of the two to the top of my reading list now.

:D

Food and love are very often entwined for me. I think I need to get ahold of this book.

It would make me so happy if you could write down the custard josephine baker recipe!

If you search Google Books, it comes up :D I don’t want to get AS in trouble for screenshotting it, but the recipe is definitely available in full if you search the text.

This post has changed my life. I am forever indebted to you, Autumn, for bringing this glory into my universe.

I am fascinated with the cooking and eating habits of our premier women poets. Emily Dickinson was noted for her baking (see http://lavenderpoems.com/emily-dickinsons-lesbian-love-poem/ ), and now I learn why our beloved Gertrude Stein had such girth — lol. Truly, the eggs recipe sounded over the top in terms of calories and butter. But if that is what it took for her to write her amazing poetry, so be it. Thank you for the review of the book!

Emily Dickinson made really good gingerbread and she used to drop little parcels of it out the window for the neighborhood children.

Oh this article made me laugh out loud several times. Our small town public library has the children’s book Gertrude Is Gertrude Is Gertrude Is Gertrude which I of course had to purchase and add to my library of children’s books. Thank you, Autumn!