Cisgender photographers with privilege and access to the art world regularly ask trans people to collaborate with them out of pure trust in their good intentions. The trans people who become their subjects believe that the images will not only appear flattering, but will also act as a means toward more access for trans people, too. But why is this dynamic one-sided? What would it look like if the exchange were a two-way street, with artists placing equal stakes back into the projects and ideas of their subjects when approaching collaborators who come from marginalized backgrounds?

The Illuminations Grant is a testament to what can happen when cultural producers invest their energy not just in the documentation of trans people, but also in creative solutions for their lives and careers. Providing an unrestricted $10,000 to one artist per year, the award funds Black trans women creatives while offering them guidance in the art world through studio visits with each of the judges on the panel. In its first cycle, the judges consist of artists Kiyan Williams, Juliana Huxtable, and Texas Isaiah, as well as curator Thelma Golden. Funded by contemporary photographer Mariette Pathy Allen, the Illuminations Grant allows Black trans women to be more than the object of another person’s gaze by interfering with the culture of extraction permeating modern trans representation.

Mariette’s work comprises a largely unseen photographic history of transness, one that developed prior to contemporary debates around representation. Before the emergence of “trans” as a gender identity, she was a cisgender photographer depicting a multitude of gender non-conforming individuals, mainly middle and upper-class white people she met at crossdressing conventions throughout the 1980s. Her images were groundbreaking because at the time, nobody else wanted to look at trans people in a humanizing light. In the 90s and early 2000s, one can see her subjects diversify in age, race, and class, most notably in the images of trans and intersex youth. In the 2010s she photographed trans women in Burma, Thailand, and Cuba.

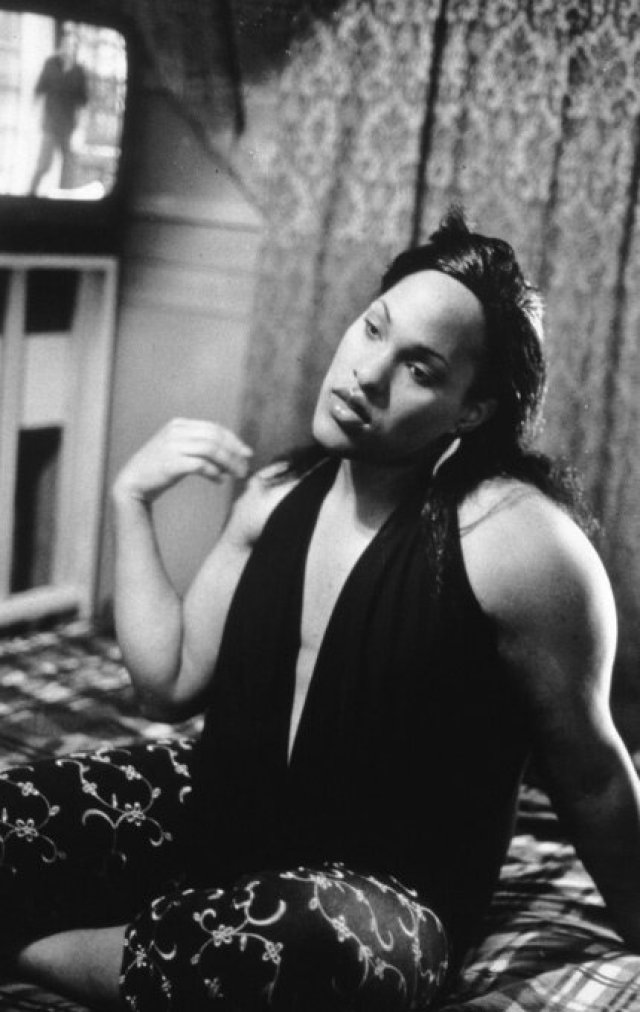

Monique in her room, Queens, NY. Image by Mariette Pathy Allen

I met Mariette through a client at my printing lab work-study position in college, and she hired me at first as an assistant and later doing archival projects. Because my art practice centers on the idea that trans people can tell our own stories, I hold a general skepticism of cis artists who build their careers documenting trans communities. I began making images of myself and my friends in college at a time when I had been putting myself online without much critical thought. When people in turn approached me about being the subject of their photography, I at first thought I could find empowerment in the exposure I would receive. But I soon started to feel exhausted by cis artists asking me to use my image in whatever way they deemed fit, often without compensation or credit, with the sole promise of exposure. I became somewhat neurotic about my self-image, and decided I only wanted myself or other trans people to manipulate my likeness, or to control how my body was projected back out into the world.

As I learned very intimately how it felt to have my transness extracted by cis photographers for their own use, I also recognized that my whiteness protected me in certain ways. I had the opportunity to interact with the industry as an artist instead of just a model, as well as from a technical standpoint doing archival work for Mariette. Furthermore, I knew the power dynamics of the art and fashion worlds were not the most oppressive forces faced in daily life by most trans people. That being said, I realized that I had a responsibility to encourage other white artists to consider alternative models for collaborating with marginalized subjects, especially considering the fact that Black trans people face far greater levels of industry exploitation than I ever did.

In working for Mariette, I challenged myself to move beyond my discomfort and look at the bigger picture of what we could accomplish. Even though I’m a trans person, and Mariette and I are both white, we both create photos of the trans community that complicate pre-existing narratives fed to mainstream audiences. The reason I asked Mariette to make the grant in part was because I realized, as a trans artist making work for my community, I could be complicit or even participate still in the same exploitative practices embedded within trans visibility myself.

Although making images of individuals within my own community spoke to the power of trans-directed narratives, part of the dialogue I was having centered on the double-edged sword of visibility: there was a danger in putting Black trans people under a microscope without doing anything to change their material surroundings.

By partnering with Mariette, we could put our energy into engaging Black trans people with the intention of interrupting the harm caused by the various traps of visibility. In her 2017 anthology entitled Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, filmmaker, and archivist Tourmaline writes, “If we do not attend to representation and work collectively to bring new visual grammars into existence (while remembering and unearthing suppressed ones), then we will remain caught in the traps of the past.” If the ultimate goal is for people to tell their own stories, white and cis people must understand that their stories will have disproportionate influence on the landscape of the art world. Unless something changes, the environment of white supremacy in contemporary art and culture will allow white artists’ visions to be received as the predominant narrative, while Black narratives will continue to be systemically erased. Although Black trans people are telling stories of their own, they largely get obscured by an industry that historically excludes people on the basis of race, gender identity, and class. As long as the field remains built around whiteness and cisness, these traits will prevail as over-exaggerated norms.

Although the Illuminations Grant’s launch coincides with the current rise in community-based mutual aid efforts, the award has been in the making through a full year-long creative process, in which our team devised strategies to counteract the art-world trappings of the past. During a series of conversations with consultant and artist Aaryn Lang over 14 months ago, we realized artist awards specific to trans people were few and far between. When I eventually told Aaryn that Mariette was finally on board with the project, Aaryn responded, “why not make it for Back trans women?” The idea set in motion a series of events that none of us fully anticipated, and we eventually hired her as a consultant. We were met with skepticism along the way: many institutions didn’t understand the need for a grant specific to Black trans artists. Aaryn’s presence gave a new meaning and legitimacy to the project.

The Illuminations Grant addresses an important question: why aren’t there Black trans women in positions of power within the art world?

While it may have been groundbreaking for Mariette to document gender non-conformity in the 80’s, her work in this contemporary moment had the potential to grow. Aaryn’s engagement strengthened the impact of Mariette’s platform which already had institutional and financial backing — what it needed was community input. In trusting in Aaryn to guide the grant making process, she took liberties that center Blackness within the grant’s structure. For example, the judge’s panel is entirely comprised of Black artists and a Black curator. Prioritizing Aaryn’s voice resulted in the white people involved with the grant to give up their power in deciding whose art is deemed worthy of recognition, allowing Black people to have total control in this process.

Furthermore, opportunities to meet with judges for studio visits offers support beyond monetary means for Black trans women artists. Not only will the winner of the grant get feedback and mentorship from other Black artists and curators, they will also engage in critical dialogues with stakeholders and industry professionals who influence the art world more broadly. The Illuminations Grant addresses an important question: why aren’t there Black trans women in positions of power within the art world? It is our collective responsibility to continue answering this question by creating new ecosystems in which Black trans women can thrive as artists and as people.

i’m so glad this grant exists, and it was really interesting to hear the backstory on how it came to be.