Photos courtesy of Chanel Moye, Ellanie Emanuelle & Seher Roychowdhury.

One evening following Afropunk, four friends walk into a venue. They go up three flights of stairs and find seats at the back of the small bar. One by one, womxn are introduced to the crowd; they dance around the stage, sensually removing silk gloves and sparkling dresses to Burlesque Blues and the likes of Peggy Lee, B.B. King and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins.

I’d lost some interest in this samesie-performance-style by the time Poison Ivory was introduced, but when the music started and I saw the stage blessed by the presence of a beautiful black body, my attention was on her. I’d never seen a black burlesque performer before. She spread her white feathers out like angel wings, displaying such grace, not looking at the audience.

She ended her performance by pouring champagne down her arched back as we watched it drip between her legs. They say you never forget your first.

![]()

I was hooked. I wanted to find that rush of representation again. From New Orleans to the United Kingdom, I tried. I witnessed burlesque performers appropriate Japanese culture, performers use the mockery of class for entertainment, drag scenes that appeared to be mostly whitewashed. I couldn’t match the high I felt watching or the same level of representation or power oozing from a performer, no matter where I looked.

Nearly a century after bisexual singer and cabaret dancer of colour, Josephine Baker, and 20 years after Rio Savant was crowned the first black queen for Miss Exotic World — Poison Ivory was named Miss Exotic World in 2016. I found myself once again at a bar, up three flights of stairs and sitting in the back of an all too familiar venue, this time with my partner (let’s call her Reesha.) The atmosphere feels different to the first time — more people of colour, more visibly queer couples, perhaps even a younger audience and definitely more black performers in the line up.

When Poison Ivory performs, I witness once again a black womxn own the stage. If only for another few minutes, we stare. We just stare and cheer and clap. White feathers spread out like angel wings — this time, her eyes flirting with spotlights; a clear and increased confidence.

As the interval approaches, Reesha convinces me to go up and tip a dollar if Poison Ivory is the one dancing on stage. The two most giggly brown queers approach the stage one by one. Lizzo’s “Tempo” plays and our tunnel vision blocks out every white guy in the room. Reesha approaches and kneels by the stage, dollar in her mouth. Poison Ivory smiles and kneels slowly bringing her face to Reesha, taking the dollar bill. Reesha slowly puts another dollar in the strap of Poison Ivory’s bra. “You’re incredible,” she whispers in Poison Ivory’s ear.

When I approach, she says “Hi” and smiles in a way that tells me she recognizes brown bodies coming to show solidarity, to say “we see you” with a tip and a kind smile. If that’s my head making up a story I’m going to keep rolling with it.

“Tempo” is still playing. I try to put a dollar bill inside the leg of her swimwear, which reads “Tits and Tattoos.” She dances down towards me quickly and I miss the spot I’m aiming for. She does it again and laughs softly. My hands are shaking. I’m trying so hard to concentrate on this; it is after all, my first time tipping a dancer and I’m trying to comfort the introvert in me. I giggle back and hide my face. She turns around and leans up against a pillar on stage. I tip her. I’m still shaking.

Burlesque, drag and striptease can allow us to embrace and tell our own stories through our work. The art of the striptease and revival of the neo-burlesque scene is giving space to seeing ourselves. In a small bar dubbed “World Famous” in New York City, Poison Ivory showed me there’s power in performance, in representation of race and of fuller black bodies. We have the power to take the stage, to own the stage, and just like my first time tipping, that stage can be our playground.

![]()

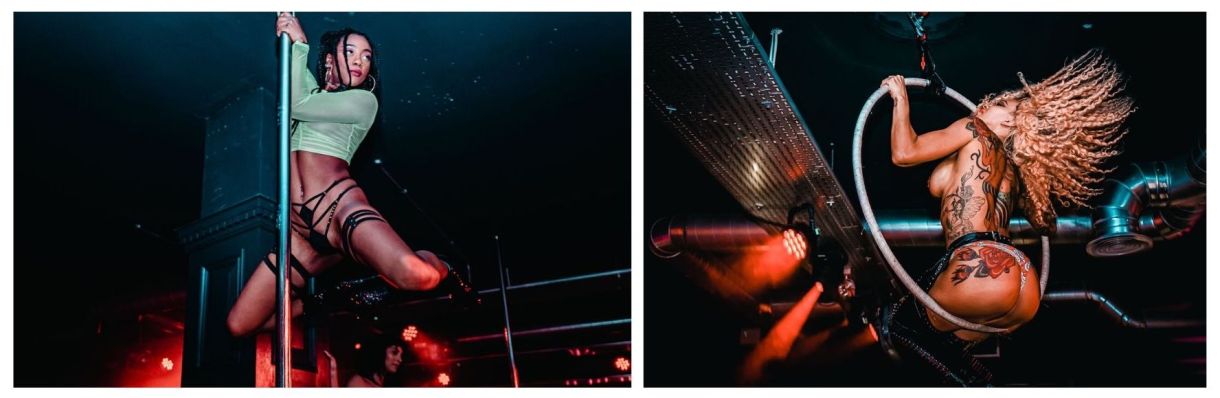

Crossing the Atlantic to the London, there’s a melting pot of queer and trans people of colour performing at nights organized by and/or for people of colour such as LICK, JuiceBox Events and The KOC Initiative.

LICK is a strip night for womxn, by womxn happening every few months (sometimes every one month if we’re lucky). The night prides itself on creating safe spaces for womxn with performances and DJ’s across running until 5AM — playing mostly hip hop and R&B. They’ve taken over London’s premier gentlemen’s clubs multiple times. Can we get a: “Yes! Take up that space!”

Three years ago, founder Teddy started LICK with no idea how popular it would get. At the time, she says, “all the gay bars were and still are dominated by gay men, often not letting womxn in, and the occasional monthly party we could find were so seriously lacking in diversity and/or our taste in music.”

Although founded by a white queer womxn, LICK has grown to have a huge impact on the community and for black queer womxn. It’s somewhere where womxn of colour seem to feel comfortable. This might be because Teddy consciously books black womxn as dancers, artist and DJ’s. “I think everyone should be doing the same. Representation especially for the black queer community is extremely important,” Teddy notes. It proves there’s a need for events that center black womxn and there previously wasn’t a market for it; LICK events have grown from selling 200 tickets to 2000 tickets for a night, selling out nearly every event in advance over the last year.

There’s still a long way to go for permanent space for queer people of colour, especially when much of the LGBTQ scene is dominated by gay bars, but LICK has been a start, evoking feelings that are reminiscent to the first time I saw Poison Ivory.

Womxn led LGBTQ/QTPOC collective JuiceBox Events is where, for the first time, I saw performers of colour, of ambiguous genders, different body types and abilities share the stage. Their event programmes burlesque and striptease performers, taking over a club for one night every few months.

Cofounders Krystal and Jenn say “being LGBTQ/QTPOC womxn ourselves we understand the frustration and disappointment in being a queer person of colour without a space to celebrate our culture and heritage safely. This is why we have created JuiceBox Events, to empower and provide a platform for the underrepresented in our community.”

At JuiceBox, you’ll see some pole work, floor work and performers straight up bringing people in from the audience, Magic Mike style. Traditionally we’ve often seen cisgender and femme people on burlesque and striptease stages. JuiceBox actively works to book amab, non-binary, MoC and masc performers. They’re also giving dom/stud performers a platform and dom/stud audiences an opportunity to be brought on stage, too. Philadelphia based gender fluid stripper Mighty performed at the most recent JuiceBox, bringing multiple people on stage.

When asked about how they see power in their performance, Mighty told me, “being a black gender fluid performer to me is to be able to control and play with versatility that gives you more freedom to express yourself. I represent gender fluid in front of the people I perform for in ways that express masculinity and femininity in a combination that allows me to interact with more kinds of people.”

Whilst I’ve never been dragged around the stage at JuiceBox, it’s where I received my very first professional lap dance. I was brought to the VIP balcony and seated on a couch next to someone I didn’t know. Together, we exchanged looks as if to say “OMG OMG OMG” and at one point we high-fived as drag king Romeo De La Cruz gave her a lap dance, and Cruz’s wife, burlesque performer and drag king, Jada Love, gave one to me. There’s something powerful about a black foursome, double lap dance safe space in the middle of a queer striptease event. Something just as powerful when the people giving those lap dances are diverse in gender presentation and body types.

Jada Love describes her time performing at JuiceBox as an “empowering experience” where she’s free to express herself on stage, “the crowd gives you love and cheers you on, which is uplifting.” Her spouse, Romeo, and quite often performance partner at events agrees, “JuiceBox is a queer experience like no other. The fact that it is black womxn led and 1000% inclusive of all bodies, genders, sexualities, cultures, languages and identities. Not just onstage with performers, but the attendees. As a performer it has given me a space to be me, let go and be respected as a person, not an object or fetish — especially as a trans enby, no T, no surgery — every humxn takes me for me, even ones that haven’t seen someone like me represent and be free openly. JuiceBox isn’t just an event; it’s a FamLITly.”

![]()

Masculine-of-center folks in the burlesque and striptease scenes might still be lacking, but London also has the KOC Initiative, a drag king collective for kings of colour founded by drag king Zayn Phallic (get it?).

The first time I saw Zayn perform I was in a basement lesbian bar — one of two lesbian bars in the UK, waiting for what I imagined would be another all-white lineup. It turned out to be a repeat of the first time I had seen Poison Ivory years before. Out of nowhere this brown king owned the stage, with a rendition of TV theme tunes through the years (including Dexter, Pokemon and Fresh Prince of Bel Air) as he changed each outfit to suit the song. Finally he stripped down to his red thong, lip syncing and gyrating to the Baywatchtheme tune; biceps hugged by red arm bands. The performance ended as he poured sun tan lotion down his chest and squirted the bottle on fans. The audience clapped and cheered for this newcomer.

Zayn was the first drag king of colour I had seen that made me think I could do that, too. Many kings embody their narratives through their performance. It’s totally possible to own a stage, have fun with it and seem comfortable in your skin. Zayn ran drag king workshops for new kings of colour, hosting a summer training that resulted in an amateur showcase. KOC Initiative continues to thrive in London, Brighton and Bristol — three major cities, bursting with queer up and coming performance and an audience eager for them.

![]()

Poison Ivory started it for me — noticing that there’s a serious lack of performers of colour in the burlesque, drag and striptease scenes. With the presence of JuiceBox Events, LICK and KOC Initiative in London, there’s an emerging pool of talent that continues to pave the way for queer performers of colour who aren’t booked just to tick boxes and reach diversity quotas. JuiceBox, LICK and KOC put people of colour at the forefront of their lineups and in the marketing of these lineups. Organizers like Zayn share their knowledge and hold space for other kings to try out their material.

Seeing myself represented in these performers has been a form of resistance, resilience and power, whether on one side of the Atlantic or the other. In a bar up three flights of stairs, Poison Ivory showed me black people exist in these spaces. She’ll always be my first.⚡

Edited by Carmen

This is great, Bailey! Thank you for sharing your first.

Thank you for reading!

love your writing and love you

<3 <3 <3

This is so great and I am insanely jealous of your experiences!

<3