Lately, I have been spending a lot of time in the kitchen — a new experience for me since my memories associated with cooking have always been tied to negative feelings towards my mother. She was always very critical, and had a scab to pick about me on every aspect of my being. Being academically high achieving, a national athlete, holding several leadership posts… none of it was ever good enough to encompass the unrealistic expectations I was held to. What those expectations are, to this day, I do not know.

As for the kitchen, my mother made it clear that knowing how to cook was an essential skill for me to possess, because ultimately my place in life was to be a dutiful wife. For her, these skills needed to be perfect. If I did not hold the knife right, or use the right pots and pans, or in other words, did everything exactly to her liking, all my efforts were imperfect. What confused me even more was learning later on that she did not wish for me to have to resolve my life around being a wife, especially if it resulted in an unhappy marriage or if I was unable to attain my own independence. The contradiction baffled me. After a lifetime of knowing her, there are still so many things I feel I will never understand about my mother and what she expected of me.

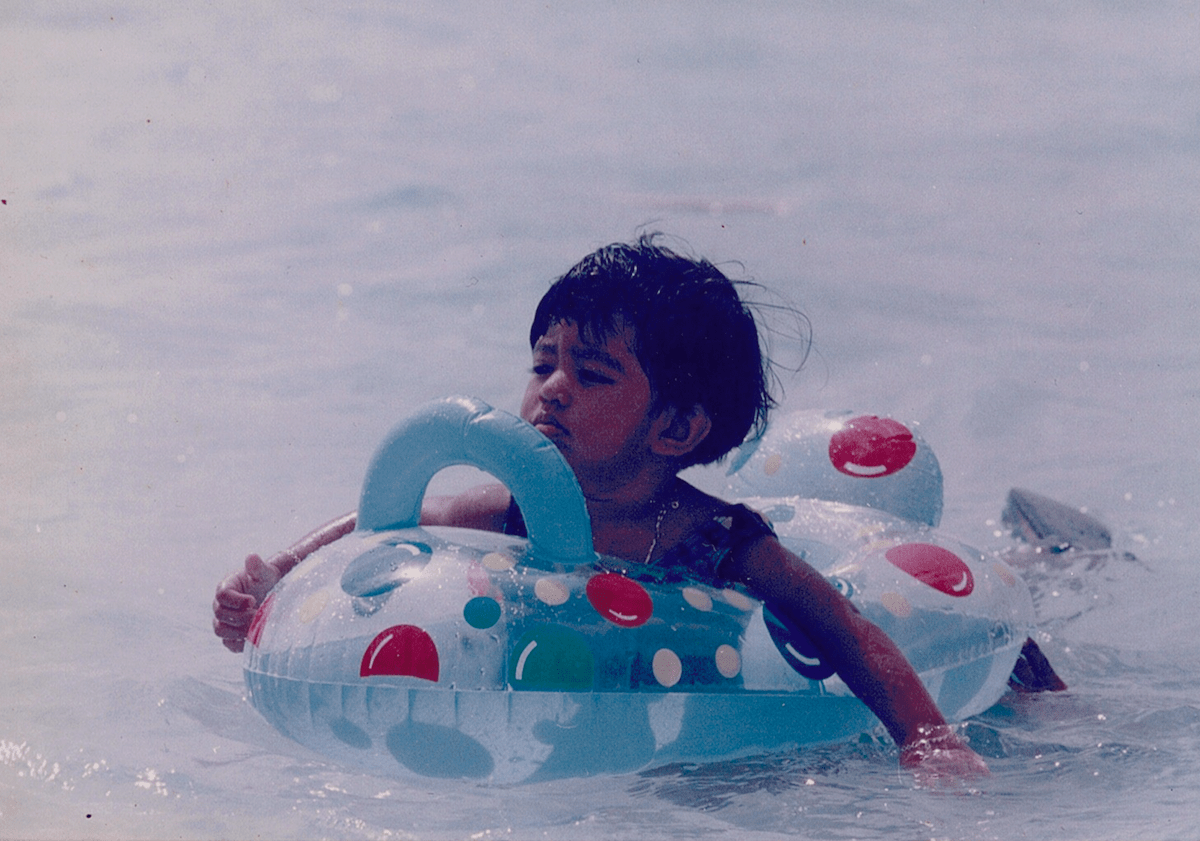

Having grown up in the Maldives with my mother’s extended family for most of my childhood, in a home shaped by community, food has always been an integral part of who I am, or so I realise. I grew up in the capital, Malé, which is less of an island paradise, and more of a concrete jungle of rapid urbanisation, where the majority of the country’s population reside. It was a relief that we often traveled to my mother’s island for our school holidays where this sense of communal belonging was even more deeply rooted in its culture. Our family was never affluent, but the food I ate was always incredibly rich.

My mother and my aunts raised themselves from a very young age, having been orphaned early on in their lives. They grew up working household chores that women were raised to do that are nothing short of unpaid labour. They were therefore excellent cooks. I don’t recall ever having had a distasteful meal in my life.

For many queer folks, our relationships with family is often complicated, and reconciliation feels impossible. Childhood and joy feels like moments stolen from us. Losing my connection with home, being forced away from loved ones, put me in a difficult place of trying to find a way back to everything I had lost. Through my journey of healing, I found that I didn’t have to forget my past to honour it, and to honour my joy amidst the hardship. Perhaps the most important lesson I have learnt though is the way I found myself reframing how I viewed my complicated relationship with my mother.

Despite being quite open about my queerness and being thrust into a public spotlight about it that opened up many criticisms from my society (including having to leave the Maldives for my safety), my mother still chooses to hold on to the child she once knew. She refuses to believe that I am what society claims — a deviant, a sinner — but in this adamant stubbornness to refuse to believe these claims, she also vehemently holds onto her disbelief that I am queer.

I won’t lie, for the longest while, it hurt. I wanted her acceptance, and I badly wanted her to call me her son. I wanted her to look at who I have become, witness my happiness with my partner, and to tell me how proud she is of the man she has raised. Though she did not raise a dutiful wife as she had believed, I like to believe that she has still raised a kind, and loving man.

My first time living abroad was back in 2014 when I came here to Australia for just the year for my diploma. It was the first time I stepped into the kitchen for myself. I learnt how to cook by myself, and eventually, it turned into my safe space of joy. Over the years since, this hobby turned into an incredible passion project. No amount of amazing takeaway restaurant food could recreate my mother’s cooking. The closest I realised that I could get to comfort food meant cooking them myself.

And now, living through a pandemic here in Australia, this time as an asylum seeker, and having spent the majority of that time in isolation with my partner opened up a new love for my safe space.

Experimenting with food is no longer just an exploration of expanding my skill set, it has become a matter of recreating a home I have lost; of creating a pathway to reconnect with my mother through my memories of her and her food. This journey of holding on to my identities has become so ingrained with my happier memories of food and childhood — of a safe space in which I was loved unconditionally. The more I learn of a new dish I attempt to recreate, beautiful memories deeply buried by trauma resurfaces. It makes me yearn to simply be without having my identities dissected and examined. It makes me yearn to simply love and be loved without condition. It makes me yearn for the simple gesture of being held in my mother’s arms.

Spending time in the kitchen and learning how to cook the comfort food of my childhood has helped me connect to my mother in ways I never expected. I realise now that I was projecting an expectation of me on her that may not be entirely fair on her. She did not have the same access to the privileges I was raised with, and she was not exposed to anything outside of her society. Her choice to raise her children and always put them first even to herself was never something she viewed as a sacrifice.

What she has done for me and my siblings, in the way she put her entire self into raising us, I realise, is to ensure that we were given more tools to gain access to privileges and spaces she could not; she prepared us for constant battles against a world in which we would be marginalized by a system designed to protect only certain people.

It would be unfair to expect her to shift her entire world view to accommodate me as I am now. Instead, what she has done has allowed me to remain in her memories in the only way she knows how, but still hold place for her love for me. In this realisation, I found her unconditional love for me. And in this way, I learnt to love her unconditionally in return.

All photos contributed by the author

RITUALS is a nine-part miniseries edited by Vanessa Friedman. The writers who contributed to this miniseries will share all sorts of rituals: rituals for love, rituals for grief, rituals for forgiveness, rituals for inner peace. We’ll publish a few pieces each week through December 31. Please share your rituals in the comments, and let our contributors know which rituals in particular speak to you.

Thank you for this. It has offered me new frameworks for trying accept my own complicated relationship with my mother.

Wow. Thank you for this. I’ve been pondering my own complicated relationship my mother lately and this resonates.

Also, the food looks amazing!

Ah, thank you for sharing, really appreciat

Sorry for accidentally posting an unfinished comment! But meant to say I really appreciate the perspective on this relationship, something I will be thinking about a lot. And l love seeing the photos, especially of the lovely food!

Thank you immensely for the lovely comments. I really appreciate all of your kind words.

Eman, those food photos are making me drool, it all looks so good! This is a lovely thoughtful essay; thank you for sharing it.

Thank you for this beautiful and generous piece.

What a gorgeous piece, thank you.