Welcome to OBSESSED, in which I provide you a reading list / media consumption list that speaks to my primary hobby: doing obsessive amounts of research into a singular topic or story for no reason. This week I watched “Captive Audience: A Real American Horror Story” on Hulu about Steven and Cary Stayner, and it’s a pretty wild saga.

Hulu’s “Captive Audience: A Real American Horror Story,” dropped in April, but I didn’t notice it until last week, and boy was it captivating! I’ve endured a lot of true crime docuseries in my lifetime, but this story — which begins with the kidnapping of seven-year-old Steven Stayner by a pedophile in Merced, California in 1973 and ends with the brutal murder of four women in Yosemite National Park in 1999 — is one of the wildest I’ve ever seen. Apparently I’m not alone in this assessment: it was the second-most-watched unscripted series in Hulu’s history, second only to The Kardashians.

And finally, just a warning that this story involves sexual abuse of multiple children.

How Was Steven Stayner Kindapped?

Steven Stayner as a child (Courtesy of Hulu)

The Stayner family — Delbert and Kay and their two sons and three daughters — lived in a small farming town of Merced, California, known as the gateway to Yosemite Park. On December 4, 1972, seven-year-old Steven Stayner was on his way home from school when Ervin Edward Murphy approached him, pretending to be a dude from the church handing out gospel tracts, as one does. He asked if Steven’s mother had anything she could donate to the church. Steven had been taught to respect adults in authority but wasn’t well-versed in the dangers of talking to strangers, so he agreed to let Murphy and his friend Kenneth Parnell give him a ride home, where they could meet his mother.

Friends, they did not give him a ride home! Murphy was actually nabbing Steven for Parnell, his co-worker at the Yosemite Lodge, who’d told Murphy he wanted to “raise an underprivileged child.” His sexual abuse of Steven began shortly thereafter and continued throughout Steven’s time living with Parnell. Parnell told Steven that his parents didn’t want him anymore and that the court had appointed him Steven’s new legal guardian. Kenneth already had an extensive criminal record, including a conviction for kidnapping and sexually assaulting a nine-year-old boy back when he was 19 years old.

Back in Merced, Steven’s parents were growing increasingly alarmed. They reported him missing to the police, and his face was all over the news. In March of 1973, the local paper called the search for Steven “one of the longest and widest missing persons investigations ever made by the local police department.” They had no leads, but his family never stopped holding out hope.

Steven Stayner and Kenneth Parnell’s New Life

A cabin where Parnell lived with “Dennis” (Courtesy of Hulu)

Parnell re-named Steven “Dennis Gregory Parnell,” and they moved around California, from Santa Rosa to Willits to Fort Bragg. For two years in Santa Rosa, Barbara Mathias, a girlfriend of Parnell’s, moved in with them, and she participated in Steven’s abuse.

In September of 1976, they moved to Comptche, a small and remote area in Mendocino County, where “Dennis” began eighth grade. Classmates remember him as “shy” but a “good kid” who had holes in his shoes. They remember Parnell as creepy and uptight. Steven made friends, had a girlfriend, and briefly played football. Even as a kid, Parnell allowed Steven to drink and smoke and drive, but Steven also feared Parnell, who’d brainwashed him out of attempting an escape. Reportedly, Parnell also abused some of Steven’s friends who came over, and as soon as an outraged parent was onto him, they moved again, this time to Manchester.

Steven was older now, and Parnell began craving a younger “son.” In February 1980, he enlisted a local boy to help him kidnap five-year-old Timmy White off the street in Ukiah. Steven, knowing Timmy would soon suffer the same abuse he’d suffered, decided it was time to plot his escape. At night while Parnell was at work, the two boys ran out into the rainy night, eventually hitching a ride to Ukiah, where they found the police department.

Steven Stayner Returns to His Family

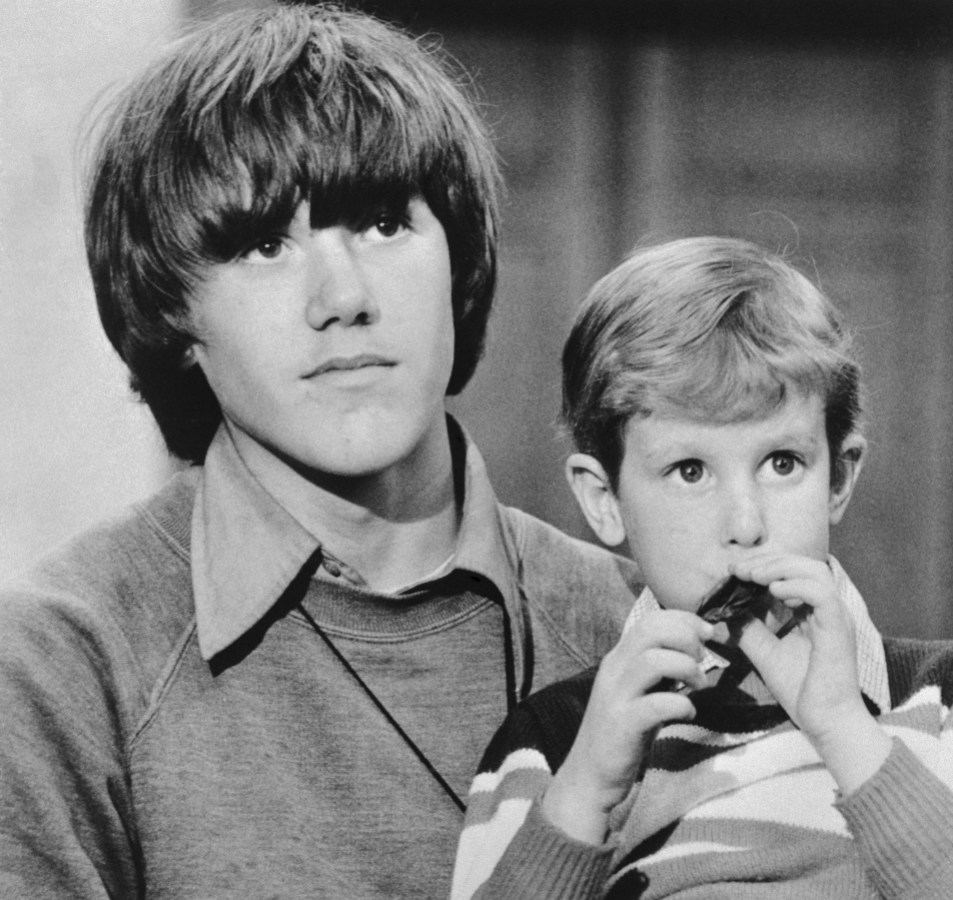

Steven Stayner and Timmy White (Courtesy of Hulu)

Stayner’s return to his family was televised in its entirety — cameras and hundreds of spectators and journalists were waiting when the police brought Steven and his dog back to his family home in Merced. He was constantly hounded by reporters and classmates were irked by the attention he was receiving. (Here’s an interview of Steven Stayner from ABC News in March 1980, one of many conducted around that time.)

At first, Stayner denied being sexually abused by Parnell. He didn’t want to talk about it, he was ashamed and he feared it’d be framed as his fault. But when a police search of Parnell’s home turned up sexualized photographs of Steven, he acknowledged what he’d endured. As he’d feared, the revelation had dire consequences. His father closed up and stopped hugging him, and he was bullied at school with gay slurs. His father also refused to send him to therapy, because he scorned psychiatry in general and saw therapy as a tool for weak people.

Steven drank heavily, did a lot of drugs, dated lots of girls, and eventually dropped out of high school. He told Newsweek that “Sometimes I blame myself. I don’t know sometimes if I should have come home. Would I have been better off if I didn’t?” Undoubtedly, Steven was carrying around so much unprocessed trauma, it’s a wonder he was making it through the day at all.

Meanwhile, Cary grew increasingly bitter about his family and the entire world’s focus on Steven, telling an interviewer:

The way I see, just about anybody would have done the same thing in his shoes… We never really got along that well after he came back… All of a sudden Steve was getting all these gifts, getting all this clothing, getting all this attention. I guess I was jealous. I’m sure I was… I was the oldest and all that. Then all of a sudden it’s gone. I got put on the back burner, you might say.

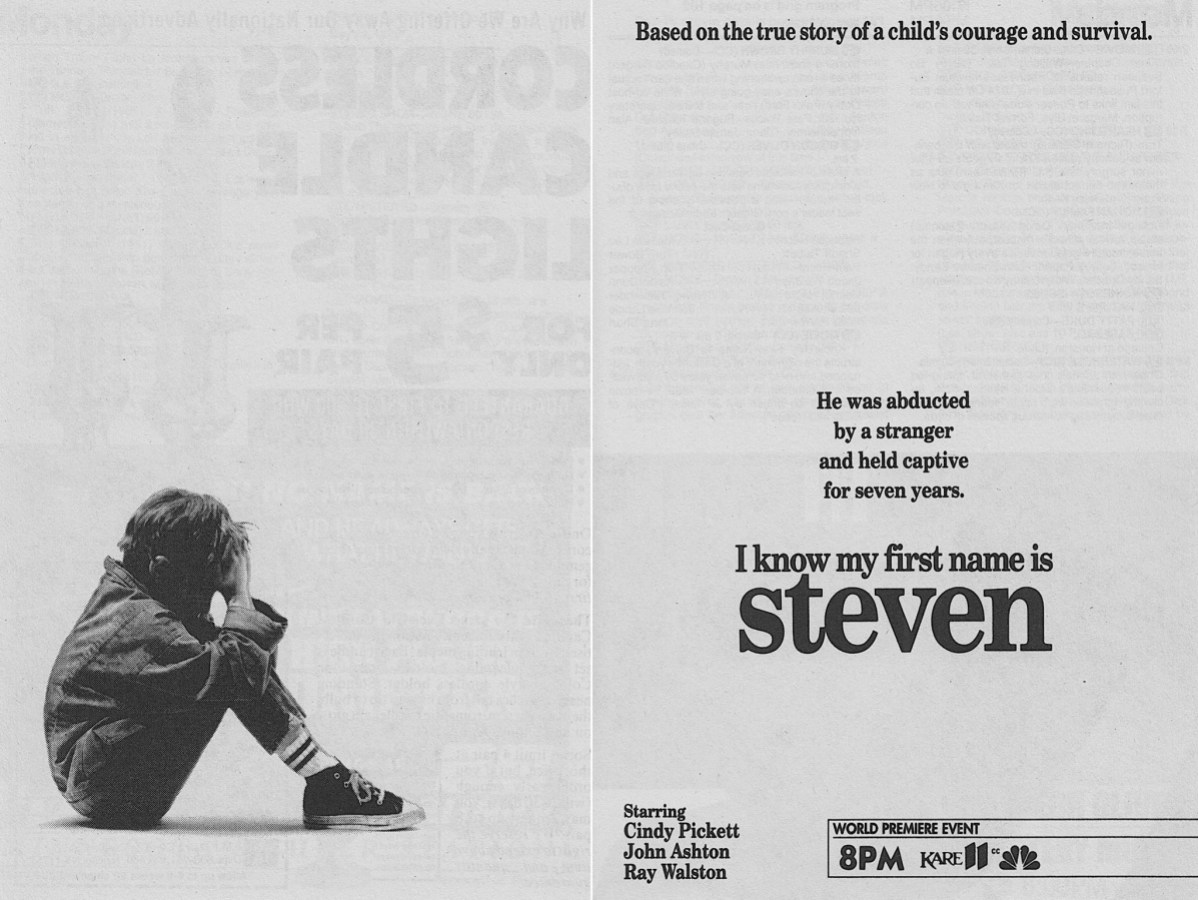

“I Know My First Name Is Steven”

Mike Echols’s book about the kidnapping of Steven Stayner, “I Know My First Name is Steven,” was considered by the Parnell family to be “pornographic,” dwelling in lurid details. They felt slightly better about the two-part TV mini-series that debuted in 1989, for which the family was consulted. (“Captive Audience” utilizes the hours of conversations between the filmmakers and their interviews with Steven and the rest of his family to tell his story.) Nearly 40 million viewers tuned in, making it NBC’s highest rated miniseries in five years.

(It was impossible to track it down online but I did finally find it on some guy’s Facebook page: “I Know My First Name is Steven.” And here’s an Entertainment Tonight report on I Know My Name is Steven.)

The film took some dramatic liberties, and Steven told The New York Times that he resented his portrayal as “kind of obnoxious, rude” towards his parents when returning to the family fold. Whereas the film presented conflicts between Steven and his parents, Steven said his actual problems returning home were with his siblings — he’d lived alone and lawlessly for so long, it was difficult to share and follow “family rules.” Steven added that “relations with his brother are still strained.”

“I Know My First Name is Steven” was a massive hit, and inspired a new bout of press attention to the Stayners. By that point, Steven had gotten married and had two children, was working with child abduction groups to educate kids about kidnapping and had a job at a pizza parlor.

The miniseries was nominated for multiple Golden Globes and multiple Emmys. The night before the Emmys broadcast, Stayner was hit by a car on his motorcycle on his way home from work and died of fatal head injuries.14-year-old Timmy White was a pallbearer at his funeral.

The Prosecution of Kenneth Parnell

In March 1980, The San Francisco Examiner published a piece called “Twisted Love: A Portrait of Kenneth Parnell” which attested that Parnell had been “disturbed” all his life, beginning with trying to pull out his own teeth as a child, then moving on to theft and arson. Parnell has both claimed he was abused as a child and explicitly denied he was abused as a child. He told doctors at a hospital where he was treated that he “began to participate in homosexual activities” at the reform school where he was sent for stealing a car. At the age of 18, he married a 15-year-old girl, and they had a daughter and divorced four years later. His first arrest for child molestation occurred shortly thereafter (he was 19, the child was 9) and he was sent to a psychiatric hospital, from which he escaped twice.

His psychiatrist determined, in an age when homosexuality and pedophilia were considered one in the same, that he was “obviously a homosexual of the more or less dangerous type.” Parnell spent the next 15 years moving around California, briefly re-marrying a 36-year-old woman when he was 25. In 1959, he was arrested for robbery in Salt Lake City and spent six years in prison — this would turn out to be the longest sentence he’d serve for all the crimes he committed in his life. The total worth of goods stolen from that Salt Lake City store was $50.

In 1981, Parnell was tried for the kidnappings. Despite Stayner being outed as a victim of sexual abuse, Parnell wasn’t, ultimately, charged with any sex crimes, as under the laws of the time, they apparently wouldn’t have added any significant jail time. Parnell’s appeals lawyer explains it like this:

“There was at the time a strong sense of what they called ‘protecting the victim,'” he said, though he pointed out that, to his mind, “protecting the victim” was really a smokescreen for blaming the victim. “Rape and molestation victims were seen as damaged goods,” Horowitz recalled. Courts, lawyers, and investigators seemed especially sensitive to the “shame” that seemed to surround such crimes.”

A San Francisco Gate article from 2003 also digs in to why Parnell was not charged with sex crimes, quoting former Mendocino County district attorney Joe Allen. The laws at the time established that because the sex crimes had occurred in a different jurisdiction than the kidnapping, doing so would require a second trial:

I wanted to charge Parnell with the sex crimes. But Steven and his mother didn’t want to go through a second trial. And my recollection is that, at the time, the sex crimes would have only tacked on two to three years more. It meant putting the victim through hell for a very modest increase in the sentence.

Parnell was convicted for both kidnappings and served five years of his seven year prison sentence. Murphy, his accomplice, got five years and was paroled after two.

Parnell returned to prison in April 2004, for offering his caretaker $500 to kidnap a 4-year-old boy for him to abuse. He died in prison in 2008 of “natural causes.”

And Then Cary Stayner Became a Serial Killer

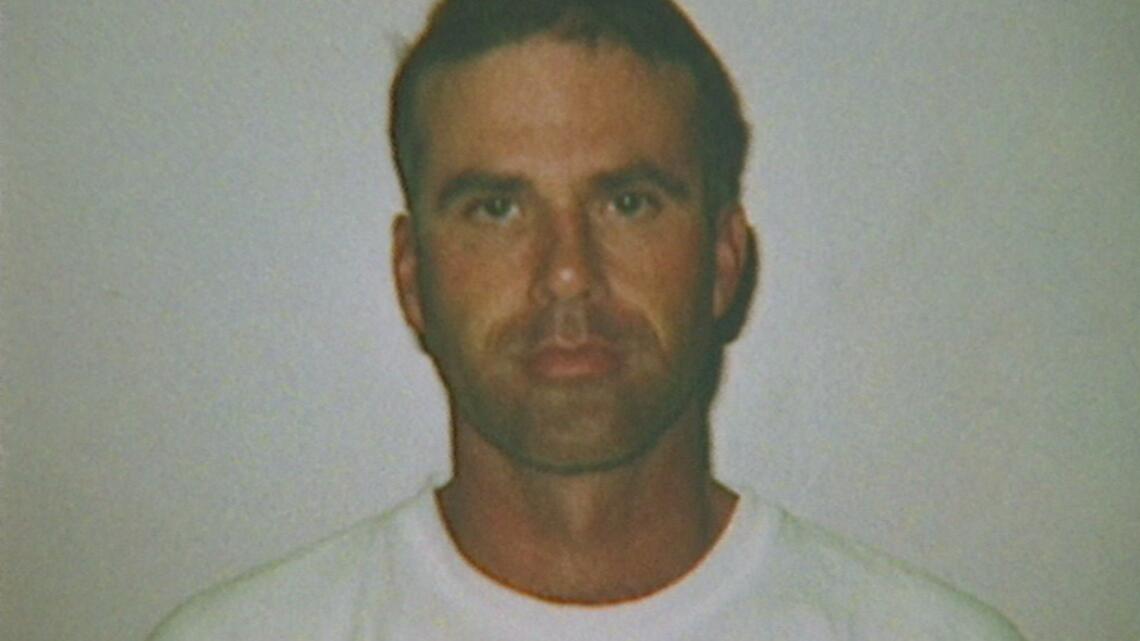

(Courtesy of Hulu)

Steven’s older brother Cary was a bit of a loner, someone who peers suspected was “struggling for decades with impulses he told others he didn’t understand.” In the Hulu documentary, his sister expresses with conviction that he was fucked up from the jump, and there are sources that say he was sexually inappropriate with his sisters and their friends. Others say he seemed quiet but otherwise normal.

Cary was handsome and a good artist, but unable to form intimate relationships with women or lasting friendships. According to later interviews, Cary had been fighting sadistic urges and hearing voices for as long as he could remember, and used pot to drown them out.

As a teenager, Cary loved smoking weed and so did his Uncle Jesse, who Cary eventually moved in with, until Uncle Jesse was murdered in 1990 with his own gun, allegedly by a home intruder. Two months later, the police said the murder “remained a mystery” but also had a very involved story of exactly what they thought happened. Cary later said he and his cousin had been repeatedly molested by Uncle Jesse. Cary eventually developed acute paranoia after years of consistent marijuana use, but kept on smoking regardless.

By 1997, he’d moved to the Yosemite valley and was working as a maintenance guy at a 206-room motel, Cedar Lodge. In February of 1999, three women who’d been staying at Cedar Lodge while traveling in Yosemite were found murdered: 42-year-old Carole Sund, Carole’s fifteen-year-old daughter Juli Sund and their family friend, sixteen-year-old Silvina Pelosso. The murders were all over the news and remained unsolved in July, when 25-year-old Joie Armstrong was found headless in a creek. Cary was arrested after a woman at the nudist resort he’d escaped to called a number she saw on television asking for information about him.

Stayner confessed immediately, to sexually assaulting and murdering the women, but later pled not guilty by reason of insanity. A reporter who interviewed Cary in prison told Hulu that Cary’s first demand was that the journalist contact producers in LA to make a TV movie about him.

In court, a psychiatrist called by the defense testified that the Stayner family had a long history of sexual abuse and mental illness, including “a history of dysfunction dating back three generations.” A doctor testified that Cary was “mentally impaired.” He was found sane and convicted on three counts of first-degree murder with special circumstances and one count of kidnapping.

He remains on death row at San Quentin Penitentiary in California.

What Happened to Barbara Mathais?

Police tracked down Barbara Mathais, who’d been listed as Steven’s “mother” while they lived together, but she was never charged for her participation in Steven’s abuse (although neither was Parnell, so!).

To be clear, I’m not an advocate for incarceration as a solution or as a measure of “justice” in general, but! Barbara was somehow also hailed as a “good guy” in the story. Bafflingly, she was given a “reunion” with Steven, apparently became friends with Steven’s Mom, testified against Parnell and claimed she had no idea he wasn’t Steven’s own kid. She told journalists that Steven “was always a nice boy and he called me ‘Mother’ like my own kids did.”

By 1981, Mathais’s son, Lloyd (who’d allegedly also been abused by Parnell), had been murdered by his stepfather. Her other son, Robert, was in jail for drug, firearm and oral copulation charges.

What Happened to Timothy White?

White testified in 2004 at Kenneth Parnell’s trial for human trafficking and attempting to kidnap a child. He became a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy in 2005.

In 2010, Timothy White died at the age of 35 from a pulmonary embolism.

More:

Inside the Monster by Katy St. Clair for The East Bay Express (2003) – The author discovers Parnell lives in Berkeley and sets up an interview with him after the author of I Know My Name is Steven assures her “he’s only a threat if you’re a child,” and they go out for dinner and my lord, Parnell is a real piece of work!

Voice in the Dark, by Sean Flynn for Esquire (2004) — Flynn recounts the major events in Cary and Steven’s lives and crimes, and interviews Cary in prison, and Kenneth Parnell, who was then living alone in a white cement row house in Berkeley.

Overshadowed All His Life, by Stacy Finz and Meredith May for San Francisco Gate (1999) – About Cary’s life and history prior to the murders.

Blood Brothers, by Sarah Beach for Salon (1999) – A friend of Steven’s when he was in Compatche on her memories of Steven and a plea not to conflate his story with that of his brother’s/

This response from a judge to Kenneth Parnell’s motion (1981) that charges against him her either unsupported by probable cause or barred by the statute of limitations is really choice. It seems like Parnell actually attempted to argue that because Steven was kidnapped seven years ago, it couldn’t be prosecuted due to a three-year statute of limitations.

The California True Crime podcast did TWELVE episodes on this topic and their website also features show notes with links for all their episodes.

20/20: Evil in Eden – Special on Steven and Cary Stayner. You can also watch it in multiple parts on YouTube.

Hi! Part way through reading this and I want to flag that you describe the person who Parnell marries at 18 as “a 15-year-old woman” which is not great phrasing! At that age she’s a girl/child. Maybe the text could be edited?

good call, thank you

No, thank you!

It’s crazy how these two things shaped my life. For some reason, the episode of “I Know My First Name Is Stephen” that I saw when I was eight years old has lingered with me all these years. I had internalised a lot of the era’s fear around the abduction of children by strangers.

Hi! Just need to point something out: in your synopsis of Parnell’s background, you describe him as marrying a 15 year old “woman.” Fifteen year olds are not adults. She was not a woman; she was a child. Important distinction, thanks!

It’s so wild how formative these two events were for me. I remember watching “I Know My First Name Is Stephen” when it aired (I was 8) and it stuck with me for so long. The 80’s were such a time of paranoia about child kidnappings by strangers and I had internalized a lot of that.

When the Cary Stayner murders in Yosemite happened, and I found out the connection with Stephen Stayner, I was totally in shock. By that point I was 18 and had been to Yosemite several times but also was raised by a very paranoid, anxious, fearful mother (who I bonded with by watching forensics shows and true crime series lol), so it just added to my fear of stranger assaults and kidnapping that I had felt as a girl/woman. It took me so long to move past that and see that these were pretty extraordinary happenings that were mostly coincidentally connected to each other. I camp and hike and backpack as a solo woman, and I do fieldwork as an ecologist in a lot of parks and public lands, and there’s always a little fear in the back of my mind, but I’m glad that it’s at a level where it’s much healthier and doesn’t stop me from experiencing life the way I want to.

I don’t think “excited” is the right word, but I’m now very interested in checking this series out.

Just realized that it’s “Steven” and not “Stephen” Ooops!

i never saw the miniseries at the time but i came across so many people when lost in various reddit threads etc who had and who it made a big impression on!

it’s so fascinating to hear about the reverberations stories like this have on our personal lives, like the fear that you developed around visiting national parks as a woman.

I’ve never heard about this sad case :( Thank you so much for covering it here!

I remember watching “I Know My First Name is Steven” because I remember that scene where the line is drawn from.

I always thought it odd recall it whenever it comes up of course you now tell me it was a massive hit and seen by many. Ha! The days of network television when we only had 3 channels to choose from.

Hello, everyone!

I knew a lot about this case because I know about Joie Armstrong. She was one of the women who Stayner murdered (as mentioned in this article), but the end of her life wasn’t her story — she lived such a full and beautiful and badass life it’s important to know about her.

Joie was super headstrong and ambitious and was a Yellowstone Institute naturalist. She was a young and brilliant femme (probably also queer I’ll let ya’ll look at photos and decide), in an overwhelmingly majority white male field and she became an outdoors educator to tell different stories. She was an experienced hiker and had begun to seriously climb, having completed a partial scale of El Capitan. She lived just inside the park in a cabin with a garden she tended, where she stowed a bronze hand-fill bathtub outside so she could bathe in creek water under the stars. She wrote in letters so often how much she deeply loved her life and calling.

When she was murdered, her family and the park created the Yosemite Armstrong Scholars to keep Joie’s dreams and actions alive. Every summer for the past twenty years, a group of 15-18 year old women and non-binary femmes go to Yosemite for twelve days. The groups are adamantly trans inclusive, and prioritize QTPOC and white gays and theys, BIPOC, as well as low-income youth for selection. (I don’t want to hide that it was really super white for many years, but it seems like they’re concretely changing that now.)

My platonic queer soulmate friend of the last decade, who taught me how to backpack in my early twenties, was lucky enough to go on this trip when she was fifteen. Now she’s an astronomer because of how she fell in love with the stars. On the trip, alumni hike out in the night with foot baths, salts, salves, and nail polish to care for each other halfway through the trek. It’s to imbue community care as essential for when the going gets tough. And they do this ritual in particular to honor and acknowledge Joie. Reminding us of her as she lived — alone and powerful, under the moon in her bathtub, tending to her body, dreams, desires, and the world around her.

I worked with Carey up in Yosemite, we worked for the same company at 2 different hotels. He worked for Cedar Lodge and I work for Yosemite View Lodge. I’ve had drinks with him at the bar up there. At the time of the murders I was down in San Diego so I was never a suspect or interviewed by the FBI, but people wanted to rent the room that the murders took place in, they eventually turned it into a storage room. On my way home every day Carey would be pulled over to the side of the road next to the Merced River and would be there sun bathing. he was such a good looking guy you wouldn’t of thought that he would of done this. At the time when I was up there I had just graduated from high school, I had no idea at that time that something had happened to his brother prior.

Fascinating story! I love stories like this! I always look forward to a movie or series in this genre! And after reading this story, my blood froze in my veins!

I was looking for another article by chance and found your article totosite I am writing on this topic, so I think it will help a lot. I leave my blog address below. Please visit once.

“I Know My First Name Is Steven” is a heart-wrenching and emotionally charged true crime story that follows the life of Steven Stayner, who was kidnapped at the age of seven and held captive for seven years. The film explores the trauma and psychological impact of Steven’s abduction and the difficulties he faced trying to adjust to life after his escape.

The movie does an excellent job of portraying the complex emotional journey of Steven and the devastating effects of child abduction. It highlights the importance of timely intervention and support for victims of abuse and trauma.

The acting in the film is top-notch, with impressive performances by Corin Nemec and Luke Edwards, who play Steven Stayner at different stages of his life. The direction and cinematography also add to the overall impact of the film.

Overall, “I Know My First Name Is Steven” is a must-watch for anyone interested in true crime stories and human resilience in the face of adversity. It is a poignant reminder of the importance of protecting children and supporting victims of abuse and trauma.

Follow up on here’s how it really happened spins more truth as to what set Cary off to kill the women at cedar lodge. They were not the intended victims-he actually was grooming another mother and her 2 children to murder them. Gotta go watch the episode for more to this story-crazy!