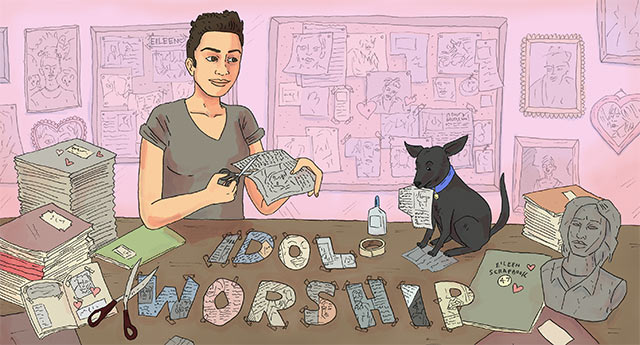

Header by Rory Midhani

Welcome to Idol Worship, a biweekly devotional to whoever the fuck I’m into. This is a no-holds-barred lovefest for my favorite celebrities, rebels and biker chicks; women qualify for this column simply by changing my life and/or moving me deeply. This week we’re going back in time to the Factory and wearing a lot of black with Warhol’s first muse Edie Sedgwick.

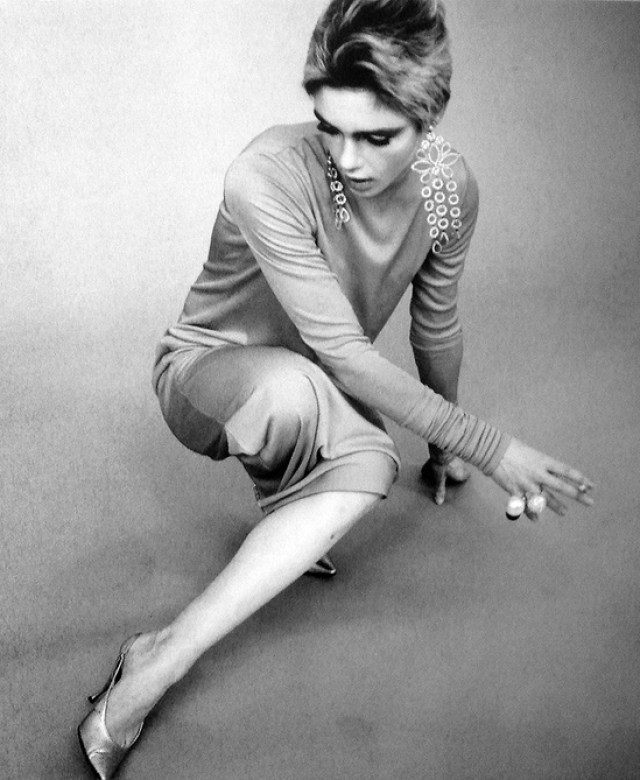

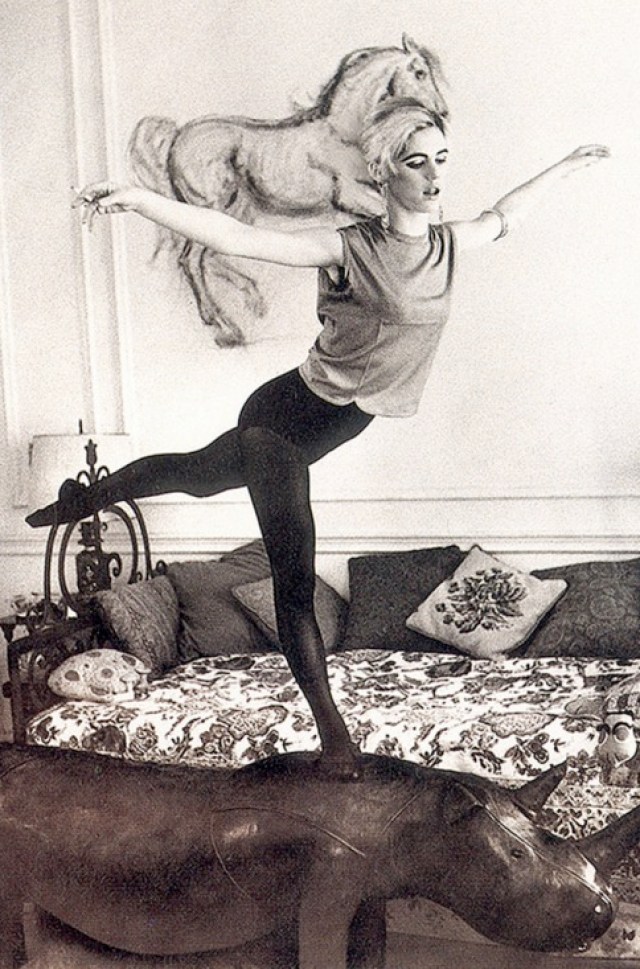

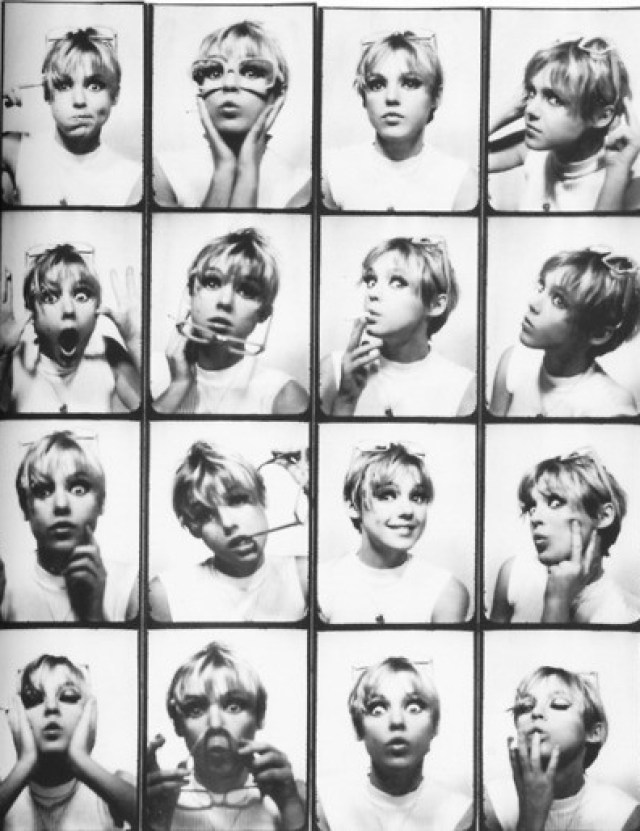

Edie Sedgwick’s image has inspired countless human beings to wear more stripes, more tights, and more eyeliner. Her boyish frame has come to represent the Warhol sixties and her unique and modern style revolutionized the fashion industry as the 70’s bloomed in New York City. Edie Sedgwick was “on the scene” for under 12 months before she abruptly catapulted back from fame to where she came from: a ranch home and a fucked-up past, dead siblings and an absent father, and a familial curse she couldn’t escape. Since her passing, she has remained a ghost over the entire pop art mess, still skipping about gallery openings in sheer black tights, a fur coat, and oversized earrings. Edie is proof that anyone can be an icon. Just ask Andy Warhol.

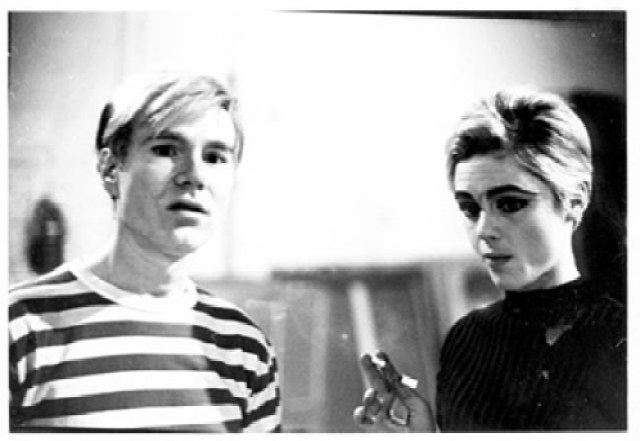

I learned about Edie Sedgwick approximately five minutes after my first-ever Google image search for “Andy Warhol.” I saw her instantly: ghostlike and narrow, beside him with white hair and racoon eyes. I learned her name was Edie and she was arguably Andy Warhol’s closest friend and first female muse. I was incredibly struck with her. Edie Sedgwick was an androgynous girly-girl, one of many tragic old money damsels in distress, a wealthy heiress with a bohemian spirit. She was eccentric and seemingly full of wonder, directionless yet maticulously put together. Over and over again when I read about her I’m told to imagine her perched on a bench putting layer upon layer of makeup onto her face. What continues to captivate me about her presence, especially during the Warhol period, is the fine mashing of masculine and feminine; the ballerina tights contrasted with the pixie-cut and the boyish frame mixed with the prim-and-proper dressings of an upscale retail therapist. I was obsessed with how she toed that line. And I was obsessed with how bravely and lovingly Andy Warhol embraced and popularized it.

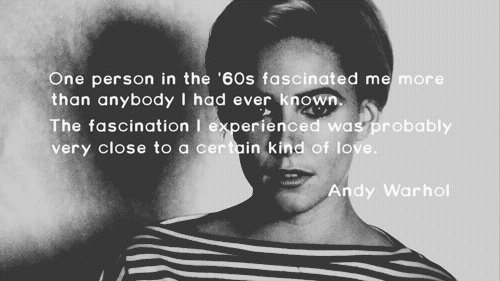

Edie was the first Factory-made icon. Warhol had spent his early years painting images of cultural icons – people he worshipped, but from afar. Edie was his first exercise in worshipping something he had extreme access to, someone he himself was intrinsically connected to. Edie represented much of his spirit and attitude toward Hollywood, fame, and idoltry. She worshipped Andy and he worshipped her and the very energy that comes from that relationship, exhibited in lasting images and footage and folklore about Edie, shines much more dazzingly than her dramatic jewelry and carefully caked-on face. Edie’s look remains a statement but her general spirit, the mere image of her, has come to singlehandedly embody much of Andy Warhol’s early work and early mission. And yet she came and went from his life in under a year.

Born into a life of abuse, tragedy, and broken American dreams, Edith Minturn Sedgwick was the descendent of our nation’s founders and the daughter of a fucked-up whack job called “Fuzzy.” He isolated his eight children, himself, and his wife away from the outside world by relocating them to a large, open ranch adorned with statues of his likeness. By the time Edie got out, two of her brothers were dead – one lost, in fact, to her father’s deeply disturbed self-loathing and criticisms directed at her sibling’s open homosexuality. Edie was borne of tragedy and wanted, very deeply, to simply find comfort, love, acceptance and happiness in New York – or at least freedom. She landed, then, in Manhattan, where all troubled girls go to find better futures. She wore tights and a matching fur pillbox hat and coat, as well as caked-on and carefully executed makeup. She made a living going to parties with her friend Chuck, living off of her trust fund in her senile grandmother’s Chelsea apartment, and doing a copious amount of drugs. Her money preceded her and she floated to the A-List. It was then that she met Andy Warhol, the man who has been credited with having created her and/or left her to die, depending on who you ask. Warhol refers to Edie as “Taxi” in his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, and says only that he was “fascinated” with her. It was hard, you see, not to be fascinated with Edie Sedgwick.

For under a year, Andy and Edie were a pair about town. It began as soon as they met, a platonic romance fed by mutual obsession and support. Edie loved Andy’s work and found his overall artistic movement to be provocative and interesting; Andy found Edie irresistable and wanted her to be in his films — making her one of the first and only women to be considered in many of the casts. Edie took Andy to parties; Andy kept her at his side at premiers and galleries. He wore a silver grey wig and she cut off her long hair, bleached it, and then dyed it grey. He wore sunglasses, and she wore fake eyelashes. She was his superstar, his muse, and his best friend. She met his mother. She talked to him on the phone. She eventually became an embodiment of his work, but at the cost of her own possibilities — Andy, unwilling and/or unable to pay her for her film appearances and general role as Most Amazing Looking Woman In Andy Warhol’s Posse, left her, eventually, bankrupt. If Edie Sedgwick is recognizable for her short-lived stunt as a famous person, she is also deserving of recognition for being one of the first celebrities to waste away in public. She set fire to multiple apartments, abusing not only speed but other drugs and most notably among them, heroin. She began hoarding and stealing drugs, as well as being discovered completely unconscious or being robbed by people she trusted when she crashed for hours or days at a time. She was known for being late, and being scattered, as well as being kind of spoiled, naive, and irresponsible. She wasted away a trust fund in mere months and later suffered as she was replaced within the Factory walls by Andy’s other projects and, later on, his other leading women. (Among these, Nico, who is also my Queen.) For Edie, other lives seemed possible but overall too difficult to execute: she was asked to be involved as a model with Betsey Johnson’s early lines and was offered opportunities to win modeling contracts, tried for roles and considered for traditional Hollywood fare, but her reputation proceeded her. Her notable skills – among them being interesting, effervescent, and really, an artist’s decorative object – seemed not to serve her as well in the real world as it had in the amphetamine-dripped universe of Warhol’s studio. So Edie went home, and there her story ends: she ran out of money and out of luck. Fuzzy was dead, but his demons remained, following her back to the mental institution he had put her in as a child as a sick form of punishment. She met another inmate there with whom she fell in love and later married, all the while attempting to overcome her considerable dependency on drugs that had once fueled her fame-filled days as Factory Starlet. She died only months after that marriage, overdosing on pills prescribed to her by a doctor for her sleeping problem. She was 28. It was 1971.

My knowledge of Edie comes primarily from folklore, which seems to be the most reliable source of any good information about a woman who may have just been a myth. The authors of Edie Factory Girl, a VH1-produced hardcover book with electric red and blue photos of Edie plastered throughout it, include one of Warhol’s assistants. The storytellers commissioned for that particular tale tell of her eventual Factory demise as fairly tragic: Edie somehow became estranged and outcast from Andy during a long and consuming love affair with Bob Neuwirth, and may have debatably been in love with Bob Dylan. Warhol may or may not have been jealous, and began to treat her coldly. Edie, overwhelmed by his rejection, began to consider other offers from fame and began to believe, according to the film Factory Girl, that her relationship with Andy had indeed never meant anything and had ruined her chances for a career. Once her euphoria at having been a part of everything slowly plateaued, Edie found herself once more struggling with demons nobody fully understood or cared about. Her closest friends at the Factory called the last footage Warhol shot of her “excruciating.” Ondine, a Factory regular and co-star of that last film, described it as “a whole reel of a total collapse of a person.” In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, the man once fascinated by Edie — and who, arguably, made her short-lived freedom and fame possible — justifies their eventual fallout as a result of her drug abuse and her need for emotional and mental support. In real life, his reaction to her death was close to silence.

Edie Sedgwick was a flash of light. If there’s anything she’s famous for, it’s going away so quickly and being so remarkable that she managed to leave a scratch on the world in under a year’s time. I can’t help but see her life as a series of extremely short bouts of excitement and tribulation. She came and she went in every part: moving quickly from place to place and Edie to Edie over the course of days, months, years. Her time with Warhol in the Factory, justifiably the only reason she exists as a cultural phenom now, was short-lived just like her time in California afterward, her return home even later, and the jumping about she’d done before ever crash-landing in his aluminum studio at all. Everything in her life happened abruptly and suddenly. Everything happened in a flash. But many times a flash can be preserved, the best example being when a flash creates a photograph and the matte and everyday experiences of a life turn to gloss. Edie did that to an entire era, dressed it up in it’s grandmother’s old furs and gave it a face people loved to look at. It’s fitting that photographs now are how she survives, and how she is best worshipped. Her look, her being, is viral. Edie, though fast to fade in the physical world, has never left the cultural silver screen. She’s been preserved as she most wanted and deserved to be, forever burned into a decade of artistic rebirth and drug-induced euphoria. Even recently, almost ten years after the Warhol tote fad and the string of Edie-inspired merch following Factory Girl, NARS released a Warhol-inspired makeup line with a special Edie Sedgwick package that I am dying to own, personally. She never left the periphery of our iconography. And yet she hardly existed in the first place.

Edie Sedgwick was born and died within what most people wouldn’t even consider a lifetime, but Andy Warhol made sure we’d never forget her. Factory-made and really, Factory-owned, she is a testament to all of his feelings about fame: that it is public, that it is art, and that it never fades. Icons never die. And neither will Edie Sedgwick.

I used to be obsessed with Edie Sedgwick, and I think she has influenced my style more than a little. This was a good read, thanks Carmen. :)

Love her. So sad that she burned up so quickly. the brightest ones always seem to.

Pingback: Idol Worship: Pop-Art Icon Edie Sedgwick « Model Agencies Blog

Read the Philosophy of Andy Warhol just after seeing the movie Factory Girl. One chapter in it is a thinly veiled portrait of her..Less flattering than I expected.

Looking forward to this series. Edie Sedgwick is a great start.

If you love Edie, do NOT watch the film Ciao Manhattan, which shows her going down, down, down and is nasty exploitation at its worst. I’d like to believe that Andy Warhol somehow cared about the people who formed his factory but, honestly, I’ve never seen a sign of it. I think the man had terrible intimacy issues, was incredibly self-loathing and projected this onto other people. Even those like Gerard Malanga, Brigid Polk and Paul Morrissey who worked with him for years and actually produced a great deal of his post-1964 output, felt that way about him. There were others who hung around Andy who genuinely did have talent, like Candy Darling, who he dumped in two seconds and replaced with uninteresting “superstars.” Which is kind of why he became so boring and ultimately obsessed with dull rich people during the 70s and 80s. Edie fits into the “poor little rich girl” iconography of the US (kind of a bizarre 60s extension of Edith Wharton characters) but she had a habit of getting hooked up with the wrong people who had no interest in her getting well and developing herself as a woman.

I’ve been in love with her since I saw Factory Girl. This was a much needed read.

Wow this just solidified for me how much I despise Andy Warhol. The way he used people up and then threw them away… his whole personality is revolting. Ugh. This story was so so sad, oh god.

She told her fellow patients at Silver Hill mental hospital that her father had molested her. If so, it’s not surprising that she became bulimic/anorexic.

Bobby Neuwirth, a close friend of Bob Dylan’s, was her boyfriend for a while. He was very caring but she was too erratic and drugged up for him to handle