The inauguration of 45 filled me with dread, despair and helplessness. The obstacles felt insurmountable, and I laid in bed with the worst cramps I’ve had since I was a teenager. It was a coincidence that I started to read How To Survive A Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS by David France. My mom, the sister of an AIDS victim, gave me the book for Christmas. She always tells me how much my uncle Adrian would have loved getting to know me, and the least I can do to honor that stolen opportunity is try to learn about the health epidemic and state violence that murdered him.

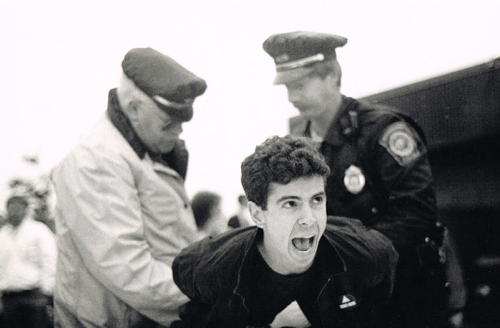

ACT UP member and TAG founder Peter Staley in an iconic image used on the cover of the documentary How To Survive A Plague.

As I dug into that 600-page book, exquisitely written by journalist David France who was writing and loving in the NYC AIDS community during the 80s and 90s, I was enraptured by the story of doctors, activists, researchers, sex workers, journalists and Wall Street executives linking arms to conquer the worst health crisis of the 20th century. No one in power cared about the plight of hundreds of thousands of gay and bisexual men, nor about the other groups predominately affected, including lesbians, trans people, and queer and straight people of color. So queers joined together and made it too expensive, too much of a publicity nightmare, and too dangerous for politicians and medical gatekeepers to not care. ACT UP and the Treatment Action Group (TAG) mobilized people with AIDS (PWAs) and allies to educate themselves and others about the reality of the disease and the available science, and then they took action.

My relationship to my own privilege and oppression had shifted dramatically after the election, and everything felt more urgent. I read this story of unbearable urgency and thought about just how much we can learn from our queer and trans forebears who made AIDS chronic instead of deadly (at least in theory — millions are living with the disease because of the medical advancements that ACT UP and TAG made possible. However, more than one million people die every year of AIDS because treatment is cost-prohibitive or otherwise inaccessible). Here, inspired by the book and documentary How To Survive A Plague, are five lessons we can learn from the AIDS movement.

1. Get press — or make your own

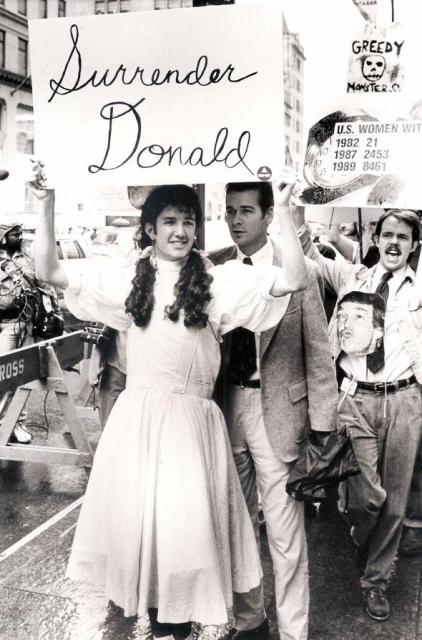

ACT UP got great press by proceeding as if they had nothing to lose — because they didn’t. Their work was a matter of life and death. Performance artist Ray Navarro went to actions dressed as Jesus, protestors chained themselves to pharmaceutical company waiting rooms. After years of not being able to get anyone to mention the AIDS crisis outside of gay newspapers like The Native, they weren’t afraid to make a scene to get a few column inches or minutes of airtime. They also made their own press. Much of the archival footage in Plague is camcorder video that ACT UP activists took of themselves and each other.

A protestor dressed as Dorothy outside of Trump Tower as part of an action against housing inequality. Source: Slate.com

In this age of viral videos and ice bucket challenges, finding ways to create publicity for your cause, action or policy aim could be the difference between a tepid, frustrating experience and a truly impactful political moment.

2. Play to your strengths

AIDS activists included organizers, scientists, doctors, politicians and artists. They included people willing to get arrested over and over again and people who put on suits and ties and A-line skirts to meet with high-level political officials and drug developers. The terminology they used was “insiders” and “outsiders.” The outsiders would make noise and raise hell to create a pathway for the insiders to get the meetings they needed to advance political and medical goals.

I used to feel shame because I don’t feel comfortable holding up signs at protests. I think my news reporter training is too ingrained. But there is so much I can do. I can write, first of all. I can give money, I can show up for friends in need, I can call my representatives. Find your niche, use your skills and leverage your power to make the most impact.

3. Seize momentum

People With AIDS and their allies were never satisfied, and that’s part of what made them so successful. When the FDA, the Bush Administration, or pharmaceutical companies granted one of TAG’s demands, they were immediately ready with plans to take it further. They didn’t just insist that companies make drugs available, they insisted they follow TAG’s recommendations for implementation and treatment.

It’s safe to assume that the institutions blocking us from dismantling oppressive systems will always try to give us as little as possible in an effort to pacify marginalized communities. Vigilance and preparedness will allow us to leverage small gains into bigger victories.

4. Check your privilege

In the early stages of the disease, HIV primarily affected white gay men. After all, the gay community was largely segregated. However, over time men of color, trans women, and cis women also began contracting the disease. They were often excluded from the leadership of activism and the from clinical trials for potentially life-saving medicines. For example, by 1986 it was clear that Black and Latino communities were affected by AIDS at disproportionately high rates, and they struggled even more than white gay male communities in coastal cities to acquire any medical attention.

Although the source materials in How To Survive A Plague demonstrate some awareness of how not OK that was, my overall impression is that this is one area where we have to do better than the leaders of ACT UP and TAG. Now as then, trans women, queer people of color, bisexuals, and other marginalized groups experience risk factors such as depression, poverty, risk of experiencing abuse, employment and housing discrimination, and more at even greater rates than white gay men and cis lesbians. We have to incorporate these understandings into an activism that is not only intersectional but that centers the experiences, work, and needs of our most marginalized siblings. For myself, my next step is to learn more about the role of trans women, bisexuals and queer people of color in early AIDS activism.

5. Be kind

I’ll leave you with this clip from the documentary of Spencer Cox, who died shortly after the film was released.

“You make your life as meaningful as you can make it. You live it and don’t be afraid of who’s going to like you, or are you being appropriate. You worry about things like being kind. You worry about things like being generous. And if it’s not about that, what the hell’s it about?”

Thanks for this article! I’ve also been reading recently about LGBT and Womens activism in the US from the 1950’s-1990’s, feeling both inspired, ashamed of not knowing my history, and a bit at a loss to figure out how to accomplish the magnitude of change that those generations of activists did. I’m working out how best I can contribute (proud to say I’ve gotten way better at phone calls!), and you gave me some more good food for thought here.

I’m not sure what you said about it affecting white gay men first is true. One of the HIV specialists where I work in one of the outer boroughs of New York said she started seeing cases in the surrounding black and Hispanic community in the late seventies (other people older than her may have seen it even earlier), and it was very unlikely that there was only one American “patient zero.” It was a particular AIDS-related infection that was noticed first in gay men.

Also, I think Act Up is the best. I think they still meet in New York and I really want to join.

You are quite correct. Unrecognized cases were seen in the 1970s in minority populations. I have to think that the first recognition of a syndrome in generally well off urban white gay men had a lot to do with (on average) better (private) insurance, dominance of the health care system by white doctors, tendency of said white doctors to have conscious or unconscious race and class bias, increasing group consciousness of gay men post stonewall combined with word-of-mouth identification of gay-friendly physicians who ended up with a large percentage of gay men in their patient rolls. The key is the ability of individual doctors or networks of doctors (practices, medical school faculty, etc) to recognize that rare symptom combination “X” is occurring in *multiple* people with a shared characteristic. Infectious disease specialists now have professional listservs for “I have a patient with symptom combo “X”, have you seen any patients like this?”. Then, it was via phone to the state health department or to the CDC in Atlanta, or FTF chat (“curbside consult”) with colleagues.

Hi! So I’m definitely not talking about “patient zero,” but the incredibly high rates in the gay white male community. Of course there were people in other communities who were living with AIDS who got even less attention and recognition than white men.

yo, why is there a line that refers to “… trans women, and women…” as two distinct categories of people? it should definitely be edited to something like “trans women, and cis women.”

The phrase “white gay men and lesbians” could also probably use a “cis” somewhere in there, to deferentiate cis lesbians from the trans women–which could also include lesbians– mentioned earlier in the sentence.

Yikes, editing fail on my part. Thanks for pointing that out.

Thank you for this! That quote at the end is wonderful and so true. Struggling to balance wanting to be liked with wanting to do what we feel is right can be tricky, so it’s great to see the tension between the two laid out in a quote like that, with a huge blinking arrow pointing to the latter.