The eight hour drive from Los Angeles to Guerneville felt impossible.

The stress of work, planning, packing, and communicating through it all piled high around me. But somehow, my travel buddy and I made it out of LA under a blanket of deep night and bright morning.

The quiet season did not roll in, it crashed into us. Going up to a queer cabin in the Redwood Forest seemed like the perfect place to recover from the jolt.

contributed by Gabrielle Lawrence

contributed by Gabrielle Lawrence

I was carrying around a growing need to “get away” from the kind of loneliness and exhaustion that finds me in the city. I could achieve this in simple ways like going on hikes, outdoor yoga, having picnics with my friends, or extended travel. The “how” of the future was calling but troubled and not quite formed enough to recognize. Did it look like a small homestead that welcomed family and friends as visitors? Did it look like a relaxing home base within reasonable distance from a bustling city? Did it look like a digital nomadic life? A sense of belonging and connection was missing from each vision.

While doing research on queer-friendly farms, outdoor initiatives, and nature projects, a friend of mine sent me a link to a panel titled “Queer Projects on Indigenous Land.” I was expecting a gathering of white queer settler colonialists — even if I couldn’t name the expectation at the time. I was expecting to feel out of place in the conversation, but the panel’s guiding questions struck me:

“How do we create liberatory spaces on stolen Indigenous land?

Where do queering and decolonizing and unsettling land intersect and support each other and miss or collide?

How are queer-led land projects and intentional spaces navigating collective approaches to healing historic harms, land access, landback, and rematriation?”

The panel was hosted by Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, “an urban Indigenous women-led land trust based in the San Francisco Bay Area that facilitates the return of Indigenous land to Indigenous people,” and featured a small circle of intentional land organizers from queer-led spaces. Nothing came of it initially — or so it seemed. I gravitated toward the BIPOC-led projects, followed them on Instagram, saved their information for another day, and let myself be inspired. I began to notice a clear difference in the mission and the motive whenever I stumbled across these collectives that spoke to the legacies of harms, deep desires for connection, and freedom that I longed to explore in community. So when I had the opportunity to begin my research months before my trip to Guerneville, I began with the questions: Why do we need QTBIPOC land healing projects? What are QTBIPOC people bringing to these spaces that makes them more sustainable, more innovative, more purposeful?

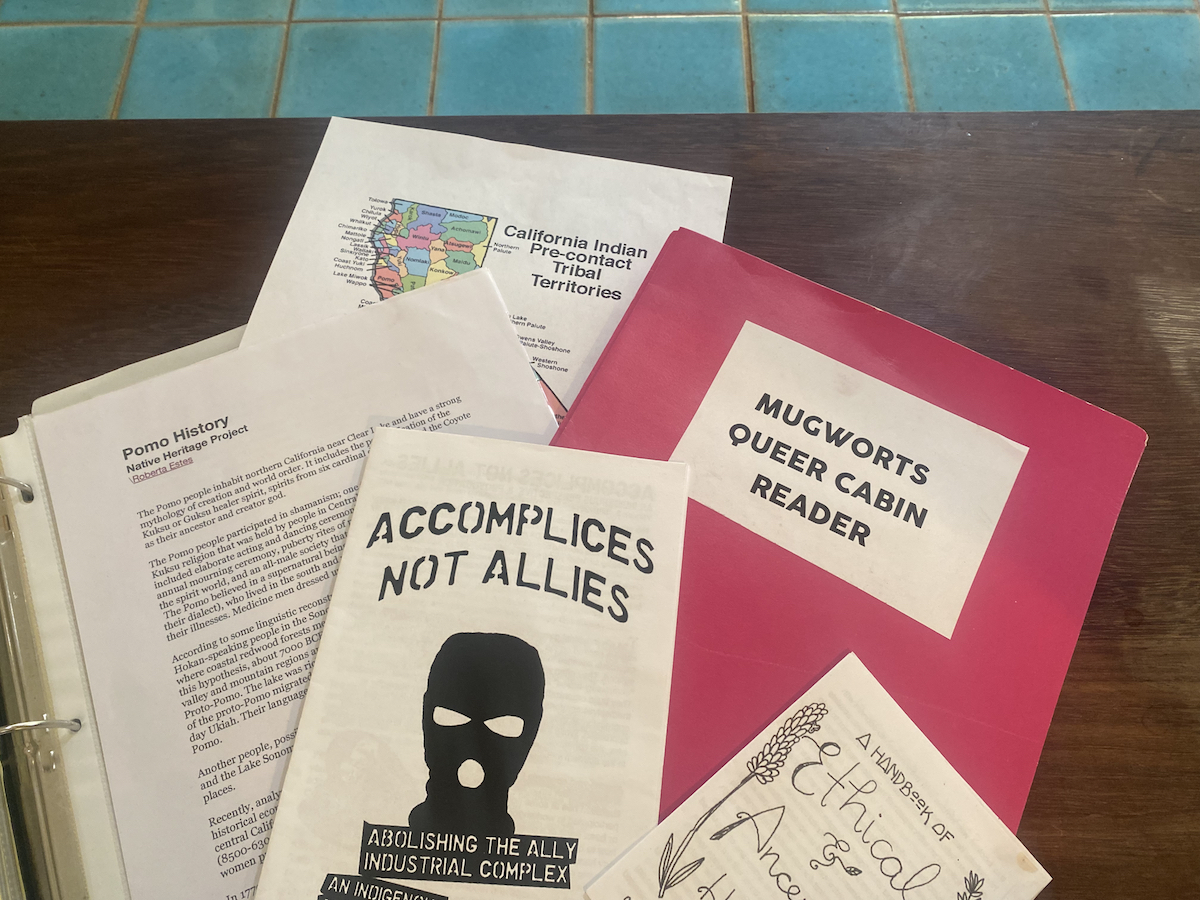

I had the opportunity to speak to a couple of organizers from the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust who are also involved with Mugworts Cabin. Mugworts “is a magikal QTBIPOC* centered cabin and retreat in Guerneville, CA on the ancestral homeland of the Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo people.” It is co-maintained by visitors, along with the collective of organizers and local tribal representatives who manage the land.

I also spoke with leaders from the Shelterwood Collective. The Shelterwood Collective is “a Black, Indigenous, and LGBTQ-led community forest and retreat center, healing people and ecosystems through active stewardship and community engagement… In Summer 2021, Shelterwood officially became the stewards of a 900-acre forest and former church camp right above what’s called the Russian River in Sonoma County, California, on Unceded Kashaya and Southern Pomo territory. This land has 10 cabins, 2 commercial kitchens, 2 multipurpose rooms, a pool, and a number of homes in which to nurture a queer Black, Indigenous, People of Color land collective.”

Eventually, the conversations and research led me to stay at Mugworts Cabin for one weekend amidst the shifting seasons. The cabin was stocked with everything we needed. All we had to do was bring our sheets, bring our food, and clean up after ourselves so the guests after us could enjoy the space as well. Our arrival felt like a warm embrace. The bamboo gate beneath a string of blue and pink flags felt like an energy field pulling us into a space where we could breathe, take care of ourselves, and let go.

photo by Mugworts Queer Cabin

This series has been a sensory experience. It has been touched and felt as much as it has been talked about and sat with. As a result of these collaborations and the guiding question, I’ve been able to identify three main areas of intention that characterize QTBIPOCs natural intelligences in the facilitation of land healing projects.

Rematriation as Sacred Relationship

Indigenous people still exist and we should celebrate their presence by speaking of them in the present, learning about their histories, and shifting our resources toward Indigenous-led projects.

One of the benefits of being in a more naturalized area is the instinct to slow down and release your grip on the wheel of life. Slowing down my expectations of all that I must see and accomplish within one day was the first step in accepting this gift of the outdoors. Slowing down my expectations of how and when I will experience the “effects” of the outdoors is an ongoing second step.

Even though Mugworts was beaming with welcome in the little gay town of the North, it took time to shake off the stress of survival. I didn’t start to feel unity between my body and my environment until the end of our stay. It took a day to settle in and come down from the stress of arrival. The following day, the gunk of all that I traveled with started to come up and out. In a place like Mugworts, there is a little love tucked away in every corner left behind by all of the visitors and organizers who hold the space. It is the magic of queer knowing and intention that helped me realize — I have to allow myself to be held if I am going to find the connection I’m looking for.

I could not force myself to arrive at healing without repairing the relationship. I had to acknowledge some things first. I had to listen. I had to rest. I had to find safety within my body and allow the love around me to point me to it. This is a process I’ve come to understand as remothering.

photo by Mugworts Queer Cabin

The space that Mugworts holds for QTBIPOC folks in their cabin is also being implemented on grander scales of land healing and management. Rematriation is an Indigenous women-led practice that widely translates to restoring to sacred mother earth. In contrast to repatriation and the violence of colonial, heteropatriarchical structures, rematriation restores Indigenous knowledges and reclaims respect for the land, the life it holds, and all that it provides. The process of remothering as outlined in Sogorea Te’ Land Trusts’ rematriation resource guide requires a deep acknowledgement of how we are connected to one another. As the guide states, “Everything has a source. Trace anything you ate or used today back to its original source and you will find yourself at land. Indigenous Land.”

When we honor this connection we understand that: All land is Indigenous land.

The foundations of this society were built by Indigenous and Black people.

Indigenous people still exist and we should celebrate their presence by speaking of them in the present, learning about their histories, and shifting our resources toward Indigenous-led projects.

With the knowledge that all land is Indigenous land, we realize that we are guests and should act accordingly by becoming conscious of our surroundings, taking good care of our environment including the people in it, and actively participating in decolonial work.

I think it’s important to acknowledge that a massive roadblock in remothering, or even in becoming more conscious of the land that we are on, is the trauma that will come up as a result. The systems we live under have caused real and traumatizing harm to our bodies as part of this ecosystem and driven wedges between our sense of self and the land — at times making us feel as if we are divorced from it entirely. So to embrace and be embraced by something as spiritually significant as mother earth who also holds our ancestors, is nothing short of a breakthrough.

Layel Camargo (they/them) and Nikola Alexandre (he/they) are the founders of Shelterwood Collective. They came together in 2016 at Soulfire Farm’s Farmers Immersion program for Latinx and Black folks. Layel is a climate justice cultural organizer who worked with artists to help shift climate crisis narratives toward centering BIPOC frontline communities. Niko is a forest ecologist and forester. After a couple of years of dreaming together, they decided to come together and eventually form Shelterwood. In 2021, they officially moved onto their 900-acre plot of land with the intention of facilitating large-scale land management for “disenfranchised communities who have been traumatized through labor extraction and extraction from the land.” When I asked Shelterwood what it looked like to navigate the trauma that may surface for BIPOC queer people coming back into relationship with the land, Layel shared:

“We had a community visioning session in December. And it was specifically for BIPOC that one day. And as we’re going around to give intros, at least 7 to 10 people were just crying. There wasn’t anything that prompted it, people were just crying because they finally had a place where they weren’t going to be policed by white people or expected to behave in a particular way.”

Layel says healing naturally occurs outdoors, knowing that our bodies release healing hormones like serotonin and oxytocin when we smell soil, breath fresh air, and touch plants. For example, they have seen survivors of sexual assault sit with their grief while harvesting plants or sowing seeds. They also noted that this work strikes a special chord with QTBIPOC folks because this community is hit hardest when it comes to rates of homelessness. So having a place to feel free and safe facilitates massive changes.

“It’s a process of homecoming. It’s a process of rebuilding our sense of selves and reclaiming our ancestry and our capacities to conceive of ourselves as creatures of the land. And it is painful. There’s hundreds and thousands of years of trauma for us to get through,” Niko from Shelterwood shared. “We do a lot of crying, a lot of holding of each other in these moments as we let that trauma flow through us… we’re also healing lineages of people who didn’t have this space.”

This past summer, Shelterwood was able to bring on two forestry fellows, one communications fellow, one community engagement fellow, and one community visioning/right relationship fellow as they build up their space. In just a month and a half of working with two forestry fellows who identify as Black, Niko has seen them go from being unable to read the landscape to being able to identify the plants around them.

“They’re becoming part of the family. And for me, that’s a big part of trauma healing, it’s finding oneself, finding one’s communities, and being able to understand the world around you. It’s starting to feel like you can be held by the oaks, by the redwoods, by the different species that are there, and that you can recognize them as kin. For me as a displaced person, that grounding is what I’ve needed to start thinking of the future.”

Without relationship, we fail to survive; we cannot conceive of new futures; we cannot move beyond whatever we’ve been indoctrinated into. In the face of societal collapse, figuring out our relationship with the land we live on is critical.

In queer and trans communities, we have a lot of practice in cultivating sacred relationships because they are how we come into our queerness. Unlearning a compulsion toward cisheteropatriarchy and defiantly living into who we are is not a solitary act. It is relational, observed, and embodied. For QTBIPOC we peel the layers back even further. We are constantly teaching and learning from each other.

Part of being able to build meaningful connections with the environment is reciprocity. Nikola, of the Shelterwood Collective, says:

“We are in a space where this land is offering quite a lot to us. There’s the very concrete things like clean air, like shade, like water… we will soon be growing food here, but we’re already gathering some food from the forest. And so there’s a lot of offering that the land has to help us tend to our own health… And so that reciprocity, that acknowledgement of the intimate relationship that we have, is a big, big piece of how we can move through this space. And I think that’s deeply informed by our queer perspective of being able to think of those trees, animals, and plants as part of our family. Queerness allows us to think expansively about what makes a family and who gets to be part of a family by virtue of us having to weave our chosen families. I think it’s very easy for us to go from ‘here’s a person that’s not blood related to me’ to ‘here’s an entity that is not actually human, but that is still a person and that deserves my kindness, my gratitude, my offerings in exchange for their offerings to me.’”

In practice, extending reciprocity to the land at Shelterwood looks like making offerings whenever they perform landscaping or taking trees down because they threaten a home or pose a fire risk does not take place without gratitude for all those entities have provided, not just to humans, but to all the creatures and organisms on the land that are also part of the community.

photo by Shelterwood Collective

Eri Oura (they/them) came to land work through demilitarization, which is the process of releasing communities from armed, government-sanctioned control that often violently destroys ecosystems. They spent time getting to know different communities and forming meaningful relationships as an organizer throughout California. Now, Eri supports Mugworts Queer Cabin as a member of the managing collective. They shared with me a few ways that reciprocity can also feel scary — especially as QTBIPOC.

“How do I show love to this place that is like, holding so much for everyone here, you know? Pay some respects before I head out. Stopping by to drop off some food or something to folks out here is really important to me when I travel between spaces. In Japanese culture, we call it omiyage, like giving little gifts. And then in Hawaiian culture they call it hello Ho’okupu. You try not to come empty handed… I sometimes struggle too with how I’m gonna support myself and make things happen in my own life, as well. That’s a balance I’m still trying to strike.”

Eri realizes that for most people, to come bearing gifts means to come from abundance. Since our experiences can be so deeply disadvantaged by violent systems it can be difficult to shake off feelings of scarcity in any form — money, energy, time, or resources. However, queer people are always making space for each other and finding new ways to show up. So for Eri, care for the land is also caring for the people there who are doing the work. That can be showing face, making an effort to remember your connections in places you travel, or bringing a small token of respect.

Ever since the pandemic I’ve realized how overwhelming the idea of having to care for others can be, especially during seasons when I’m struggling to care for myself. While sitting on the wooden bench in front of the fire at Mugworts, I flipped through a book of love notes and drawings from previous visitors. There, I felt the future becoming clearer. And it wasn’t asking me to achieve any of the things I thought I had to in order to get there. I didn’t have to grab at something for myself. All I had to do was rest, take care of myself, and take care of the space with others in mind. With extra resources, I could purchase something from the Mugworts wishlist, but that wasn’t mandatory; the only thing required of me was my presence.

Queering Unsettling

Indigenous knowledges and sciences revolve around not only local communities, but networks of communities, and the belief that we are all part of the ecology — surrounding relationships are central to survival. Queer communities operate similarly in that we choose our family and create it around us.

Investigating scarcity tugs at another important aspect of rematriation: unsettling, or unlearning heteropatriarichical and white settler-colonial ideas about the way we are in relationship. To become unsettled is to breakdown our ideas of ownership, control, and power; it is to think deeply about how to live more communally, asking questions about how we honor relationships, and choosing to be a constant learner.

I would argue that queerness and transness are an organic process of unsettling — living outside of the binary, of colonial structures, beyond social acceptance. When we think about the way one’s queerness evolves, sometimes coming into realizations about our gender or sexuality several times throughout our lives, we are in a constant state of unsettling. This gives us unique insight and applicable skills to these exploratory forms of land rematriation and land healing. As QTBIPOC, we go through the process of finding ourselves and healing the harms caused by similar structures. We have had to find language, learn to live in community, and learn to undo. Though the world tries to make it seem otherwise, our existence is healing. So what happens when we unsettle in connection with the land around us?

photo by Mugworts Queer Cabin

Unsettling can be a form of waking up and unhooking ourselves from the simulation if you will. Learning about how and why the world is in the state it’s in gives us the power to divest from the structures that are destroying the world. Without this knowledge, we are complacently participating in colonial legacies.

Layel broke it down for me this way: the climate crisis is a direct response to our removal from the natural world. We are working within a machine that is manufacturing our destruction. This machine constructs a fictional reality organized according to prejudice, exploit, and capitalism. In order to build and feed this 500-year colonial Christian-dominated machine, there needed to be a different reality. In this reality, anti-blackness is absolute, patriarchy is king, queerness and transness are demonized, and people are profit. These violences turn us away from our environment in order to survive within the machine. While we are disconnected, our natural resources are depleted. Returning and centering QTBIPOC people in this work, specifically, not only heals separation from our environment, but it also heals the genocide and eradication that precedes it.

For Layel, unsettling is unlearning the idea that we are separate from the natural world. In many Indigenous cultures, queer and trans people are woven in the very fabric of culture as keepers, ceremony leaders, and spiritual practitioners. The natural world itself was also understood as queer and trans, which has now been more popularized as an interdisciplinary practice called queer ecology. Queer ecology makes spaces for us to disrupt the ways we’ve been indoctrinated into heterosexist beliefs about evolution, the environment, and all ecological interactions by reimagining sex, gender, and environment through queer theory. There are plenty of resources for us now that help unpack the myriad of ways queerness and transness shows up in nature.

“And that’s what we’re trying to get back to here at Shelterwood,” Layel said. “When we see ourselves back into the natural world, all of this gunk from the colonial legacy starts to shed. That’s what we need to be in rightful relationship with the land.”

photo by Gabrielle Lawrence

For both Sogorea Te’ and Shelterwood, the queer family unit is a critical piece of ensuring community survival. Inés Ixierda (she/her) has seen this in action. Inés identifies as a mestiza whose experiences with displacement as a child in the Amazon forest and later in the United States informs her legacy of what land back means. She was politicized through queer punk houses where she came across other queer people who were also struggling with displacement. She began organizing with Sogorea Te’ after doing her healing work at Mugworts Queer Cabin and developing a relationship with the communities there.

“I see queerness as really disrupting heteropatriarchal family structures, which is so connected to wealth, which is so connected to the ownership of land, which is so connected to generational inequality,” she said. For Inés, releasing our attachments to things like passing on individual legacies by nature of having non-traditional family units can help us begin to leverage some of the cracks in these oppressive structures and clear out blockages in our social structures that keep us from caring for one another in more holistic ways.

From a forestry perspective, Niko from Shelterwood shared:

“What we’re seeing at the landscape level is this idea that lands and forests can only be healthy if they are in deep relationship with communities. And a lot of the white colonial modality around land stewardship is that you’ll have a nuclear family caring for a plot of land, or you might have a single forester or Ranger that’s going out patrolling a park.”

This is another form of American isolation which tasks us with building nuclear families and hoarding our resources to try and survive in isolation. Indigenous knowledges and sciences revolve around not only local communities, but networks of communities, and the belief that we are all part of the ecology — surrounding relationships are central to survival. Queer communities operate similarly in that we choose our family and create it around us. Queer community also isn’t stationary; it is connected across spaces by central values. We connect through friends of friends, online networks, groups and spaces built specifically for finding each other.

“We bring our community up with us wherever we go,” Niko said. “And that model is what Indigenous communities tending to land used to do. So part of what we’re trying to do is center this notion that queer kinship and queer family building is a key piece of the climate agenda, it’s essential to saving and restoring forests because it allows us to build communities in spaces where there haven’t been communities for 200 years because of Indigenous genocide.”

One of the first things I noticed when I got to Guerneville, the home of Mugworts Queer Cabin, was how white it was. It’s hard to feel at ease around white people for me these days. Whether it is the compulsion to perform or the discomfort of their ever present eyes, the anger and exhaustion of surviving in a society where whiteness thrives always takes its toll. Sometimes, it leaves me so worn and frustrated that I isolate myself further from my people.

However, this was the first time I found myself in the woods and didn’t feel isolated. Mugworts wasn’t just a safe house, it is a place sewn into the fabric of the land just for people like me. It is a piece of active community. It is a place I can feel comfortable bringing my needs. A place I can give back to that also gives back to me. Sometimes the concept of family feels like people you are responsible to because you share genes or formative experiences, but Mugworts reminded me that family is where you are deeply known, encouraged to expand, and cared for just as you are. Unsettled queer kinship gives us the freedom to find family in places we wouldn’t look before.

photo by Mugworts Queer Cabin

Autonomy and Accountability

Once we’re able to establish self-governance and accountability, we understand that we are all an important part of the ecosystem, that our actions impact everything and everyone around us, and that we have a responsibility to care for others just as we are cared for. In land stewardship and land healing, this means prioritizing accountability to Indigenous folks.

In quiet moments during my stay at Mugworts I found myself whispering prayers of gratitude. I reflected on how far I’ve come from feeling desolate — without community or family — without any choice but to look within and confront the roots of my quest for wholeness.

Funny enough, a core component of creating healthy communities actually starts with autonomy and accountability. You may have heard the phrase if you want to change the world, change yourself, or some version of it all starts with you. For queer and trans people, this concept has a deeper, more intricate meaning.

Firstly, our queerness and transness is so central to who we are, how we love, and how we are loved, yet no one can accept that for you. It is up to the individual to discover who they are, to find their truth, and to accept that beauty. And it is up to the individual to continue committing to that process of deep self-intimacy over and over again as gender and sexuality evolve. To quote Ms. Morrison, “Freeing yourself [is] one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self [is] another.”

Secondly, our society is constructed to oppress the very vibrancies of gender and sexuality that we embody. We are not ‘supposed’ to exist. As we know, bodily autonomy is brutally and constantly under attack for trans people in the US. So for queer and trans people, particularly those who also identify as BIPOC, we are often claiming our self back from generations of violence and destruction while simultaneously fighting for our rights to hold space in the present.

Accountability is messy business — especially when we are fighting to survive. It involves a constant attunement of self-awareness, reframing, a willingness to ask questions that may not have answers, and the bravery to confront uncomfortable truths. But what can come of it is everlastingly beautiful.

Indigenous cultures all around the world are also at the intersection of this multi-generational, multi-structural struggle against erasure for centuries. Many have also found power in the shift to self-governance which allows them to preserve cultures and ways of life that push back against societal and ecological collapse so that we may one day have a world for our descendants to live in. Shelterwood is adopting this model and queering up self-governance, and Layel shared what that looks like:

“So we look at the way that we govern ourselves, the way that we govern each other, the way that we set up particular containers for us to be able to thrive. How do we queer up how we function as core? How do we queer up how we function as an institution?”

Traditional nonprofits are set up quite differently. They have strict hierarchies and yearly staff evaluations based on out-of-touch capitalistic judgments of what productivity should look like. They have a separate but centralized HR department making impractical decisions about how to govern the whole. At Shelterwood, they use a horizontal and self-determination governance model. That looks like doing self-evaluations and then bringing those reflections to the team for feedback. Layel shared more about the queerness of that process:

“We have our own checks and balances, but also we invite tension and conflict into the center for clearing that up. We don’t have an HR department somewhere over there where we go and file complaints. We deal with our mess in house. That’s queer in and of itself. It’s organic, it’s natural, and we’re regulated by our collective mission and vision.”

photo by Shelterwood Collective

Once we’re able to establish self-governance and accountability, we understand that we are all an important part of the ecosystem, that our actions impact everything and everyone around us, and that we have a responsibility to care for others just as we are cared for. In land stewardship and land healing, this means prioritizing accountability to Indigenous folks.

For Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, this means rematriating the land, but also shifting land ownership benefits to Indigenous people. Land trusts act as legal entities that manage land and assume ownership. For organizations like Sogorea Te’ that have been helping protect sacred sites for over 20 years, trusts help redistribute equity and resources to people who have deep relationships with the land. This is a more substantial and structural contribution to the process of healing harms against Indigenous communities and coming back into a right relationship with the land.

Inés from Sogorea Te’ shared that nothing about this process was laid out. It involved lots of communication and unsettling questions. It involved all of these tools, a deep understanding of relationships, a commitment to unlearning heteropatriarichical and white settler-colonial ideas, and open conversations about how to navigate our responsibilities to collective wellbeing. Even in the creation of Mugworts Queer Cabin, Inés shared that the process required lots of back and forth. The Ohloni tribe started the project long before building a relationship with the tribes whose territory the cabin actually rests on. The questions began with something as simple as being conscious of others’ needs and boundaries by inviting their thoughts and opinions on the matter. Then how much of the space should it occupy? How is it kept up? Why should this retreat exist on this land? Inés had this to say of the challenges:

“Even asking people to come to the table is asking people with very little time to do labor. So how can we make what we’re bringing to the table even more valuable? How can we leverage all the people that we’re connected to to bring resources into the community? Because we’re coming from different territories, we’re all on different projects, and all of those territories have active Indigenous communities.”

The result is a collectively advised and maintained project that not only provides safety and rest to queer folks, but also the surrounding tribes who are doing the work of land rematriation and stewardship. Eri, Inés, and the collective of Mugworts Queer Cabin spent eight hours drawing up a collective agreement, and they have biannual meetings with representatives from all tribes involved to talk about their needs so they can make revisions accordingly. “So it’s like doing things really non-traditionally… that’s how we unlearn some of the things around ownership and decision making so that it is clearer, more radical, and more liberatory,” Inés said.

Putting all of the pieces together can be just as fluid, uncertain, and even frustrating. When I asked Eri about their experiences with collective accountability, they said having to have grace interpersonally when in community with people who have different experiences can be challenging.

“The dedication that it takes to run a land project, you know the commitment, it pushes people to really choose. There’s a choice in a lot of situations that we can make. People would choose to come live at a co-op [for example] but didn’t understand the degree of dedication, commitment, and responsibility it takes to keep something like that afloat. It takes a lot of communication labor. There are all these layers to what it takes to hold space.”

The payoff was having access to space where people could heal and develop relationships with land, but the reality of the effort can be a difficult thing for people to sit with. How do we have conversations about legality and taxes when we’ve never done anything like that before? How do we keep the space running? How will we handle conflict and crises? The responsibilities of land stewardship do not simply stop at “creating the space” for folks or even at maintaining it. Inés shared that they’ve had some amazing healing experiences at the Mugworts retreat, as have others. Those healings are documented in a black book of love notes, stickers, and drawings. Previous visitors have filled the pages with their experiences. Some people wrote about grieving the loss of their mother or reuniting with their family after coming out. Some pages are filled with drawings of nature or commemorations of Chinese new years spent at the cabin with friends. Some pages just say one word: gratitude.

photo by Mugworts Queer Cabin

The more space Mugworts opens up for liberation, rest, and healing in people’s lives, the bigger the questions get.

Inés shared:

“The space facilitated something really amazing, but it’s also the pandemic and our own homies might be on the street. Right? So how do we hold that space for just this retreat? How can we measure this value of having a space to relax when someone has a family in crisis that needs to stay in an emergency situation? Or someone needs a place to quarantine? It’s in a small town that has almost no resources and is on Indigenous land. What responsibility do we hold in inviting people to these places? What impact are we bringing into it by inviting folks from the Bay that are in much more populous areas?”

On any given weekday, when I’m sprinting from one thing to the next, these questions are overwhelming. When I’m zoning out on the weekends trying to recover before doing it all over again, these questions are simply too much to process.

However, when I am divested from the panic of surviving within the false reality that suffocates me, I realize the questions do not need to be solved immediately. The questions do not have to be answered alone. No one is solely responsible for whether or not these issues get addressed. Awareness is part of the work. Learning to be collectively minded about the resources we have is part of the work. From there, questions and conflict about how to maintain accountability will come up, but that is a sign that there is voice, and where there is voice there is agency.

Resilience: BIPOC Queers Are Doing The Work

“Everyone wants their own little slice of paradise.”

This line stood out to me from the show Impossible Builds. It’s about people who buy custom-made kit houses to build in remote areas or areas that are difficult to access. The show features mostly white cisheteronormative couples seeing how far they can stretch their dollars to build their “forever homes” in places surrounded by breathtaking scenery, or in mountainous areas, or even on the edge of a cliff.

In episode five, a white couple makes space in an isolated forest for their weekend family cottage. They clear old trees and carve out a road to deliver their moveable home, complete with a sauna, onto their isolated piece of waterfront land. As I watched, I felt a conflict forming in my belly. At one point, this was my dream. This is what I thought living in closer relationship with land had to look like.

Before my research, I knew there were individuals I could stay with, WWOOFING, and even co-ops in remote areas. My problem was that most of those options meant having to live in a mostly white space — which I was concerned would feel like a different kind of survival. Land projects and co-ops can range widely. It’s important to note that not all land projects center Indigenous land sovereignty or even BIPOC leadership. Not all land projects are built or maintained with the intent of restoring relationships and holding space for displaced peoples. I knew queer people were living together in this way but I never saw myself represented there. I knew there were even BIPOC spaces but I just couldn’t seem to access them. It fed my feelings of isolation. I felt similarly about the environmental field and my lack of “proper” training. I love the outdoors, but I’m still learning how to care for myself outside. I’m still learning how to identify and navigate landscapes. Things like permaculture, farming, forestry, and ecological certifications felt out of reach, and it frustrated me because I know my history. I know that knowledge and relationship with land is already in my lineage. Yet I still felt on the edge of something that didn’t feel or look like it was for me.

So until I could find my own little slice of paradise I dreamed, sometimes alone and sometimes with others who shared similar values, and we watched those dreams feel more impossible to achieve with each day.

I realized I wanted to live in closer relationship with the land because I found healing for myself there. Through that healing, I found a deeper compassion that allowed me to care for myself and others. Yet, the working image of an ideal future in my head was a white, western, capitalist, patriarchal, and colonial picture — an isolation and retreat I’d been indoctrinated into but did not actually want.

I want to hold and be held. All of my writing and work revolves around community. All of my wishes, hopes, and dreams revolve around bountiful and fulfilling relationship. I don’t want to experience deep healing just to live alone in the woods — growing food, doing woodwork, and going on river hikes all by myself or even with a partner.

Imagine you just moved to a new place. What starts to make it feel like home? Is it not the places you know and are known? Having a regular grocery store and knowing the layout? Finding a doctor you love nearby? Being recognized at the local coffee shop? Or knowing exactly where to go when you need to ground yourself? The future is community — it is seeing ourselves as part of the environment around us and shepherding a collective responsibility to see it thrive.

Luckily, there is a world where BIPOC queer people are already doing land healing work that builds ecological resilience instead of reactionary responses to survival. There are safe spaces that have already been conceived for us, and they’re waiting for us to dig in.

photo by Mugworts Queer Cabin

“The future is community — it is seeing ourselves as part of the environment around us and shepherding a collective responsibility to see it thrive.” !!! Thank you so much for this piece.

Thanks for writing. I work in conservation, and it’s a serious challenge to make the field less white & more connected to the communities whose land we work on. You’ve given me a lot to think about and some inspirational groups to follow!

Yes, yes, yes! All of this, yes. This piece must have taken a lot of time and thought. Thank you.

Since @Hans already echoed one of the most resonant lines, here’s another I loved: “…family is where you are deeply known, encouraged to expand, and cared for just as you are.”

This reminds me to spend some of my heal-myself time digging back into community land work; they build on and feed each other.

YES!!!! Yes! Just yes. This is such a generously written piece. And big shoutout to the incredible work Sogorea Te’ is doing!

Amazing read, thank you

Honored to read this piece ❤️

This is one of the best pieces of writing that I have read all year ❤️ Thank you for all the deep thoughts, beautiful words, important context, and challenging questions.

YES YES YES YES YES YES YES!!!!!!

thank you Gabrielle for writing this and for sharing it here, and to editors.

this work (which includes a lot of REST) is SO GAY and DO NEEDED, theae questions are ones i am deep in and have no answers for, but the company is gay (hey Movement Generation)and it feels great for this conversation to be on Autostraddle, my internet couch, in a way that is at once “yes yes yes” and challenging and illuminating!!!

cant wait to share and i hope most ppl on AS read this piece – it does so much more than the length, and i know i will be returning to read it to remind, journal, and figure shit out.

oh wow. I’m so bummed I missed this piece earlier, and so grateful it was highlighted in the year end reflections from other writers and editors. Thank you for it all