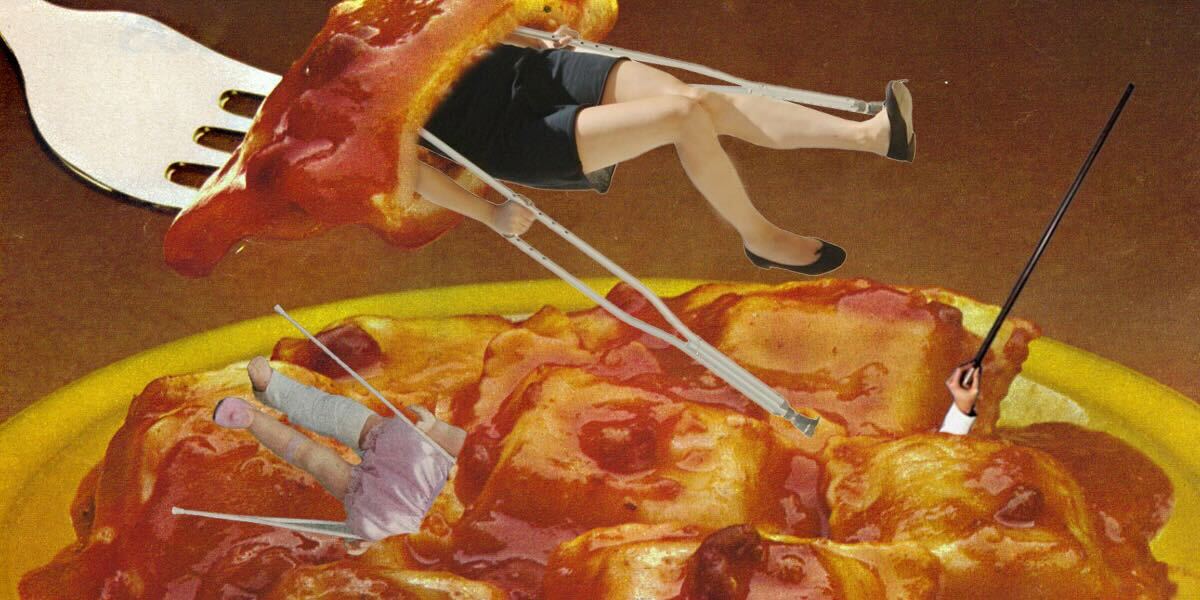

Diner Week – All Artwork by Viv Le

It’s 2 a.m. on Saturday, but the neon lights outside still shine, proudly proclaiming The Diner is open. It offers meandering conversations over perfect milkshakes, served with a little extra in a silver metal cup. At 4 p.m. on a weekday, grandparents enjoy the early bird specials of roasted Thanksgiving-style turkey with all the fixings. On Tuesday, pot pie night, the staff serves hundreds of ramekins brimming with flaky pastry, chicken, and veggies. On the weekend, people come dressed up for a baby shower, birthday, or after-church lunch.

No matter the hour, someone will always be there to open the lobby’s glass doors. The floors, sticky with that specific mix of grease and industrial cleaning products, squeak slightly under shoes. Pleather-covered benches always sit next to vending machines that offer to trade your quarters for a temporary sparkle butterfly tattoo or a tiny Spongebob figurine. Photos of community kids’ softball and soccer teams line the walls, a thank you for the diner’s sponsorship.

When I come to the diner, someone who knows me, my mom, or my mom’s friend, will greet me at the register and ask how my family is doing, while the intoxicating scent of coffee, with notes of sweet pastries and salty fried potatoes, welcomes me home.

The Jersey Diner is timeless, a staple of my blue-collar upbringing in the Diner Capital of the World. Each small town has at least one family-owned diner. They all have a ten-page menu covering everything from all-day breakfast to gyros, seafood, fajitas, Philly cheesesteaks, salads, goulash, pork roll, disco fries, hummus, French onion soup, pasta, roast beef, veggie burgers, fried chicken, a rotating display case of freshly made desserts, and handspun milkshakes. Everyone knows your name, but it feels more like a Bruce Springsteen song and less like the theme from Cheers.

These nights now blend into a blur of late-night sleepy giggles, black and white milkshakes, important debates over whether to order mozzarella sticks or chicken fingers, and drama over the latest school news and gossip. One queer couple was out, and a dozen of us would eventually come out. Outside of this group, there was name-calling and judgment. We were the nerds, misfits, weirdos, the effeminate boys who were called the f-word, and girls called dykes. But this was our safe space, and it was the first time I felt pride in being the outsider, even if I didn’t fully understand why I was an outsider.

The first time I kissed a girl, it was a secret under the guise of “practicing.” But we kept practicing. Over time, our friendship started to fall apart as boyfriends and heteronormativity got in the way of something that didn’t fit into the definitions of relationship or friendship. Sometimes we went to church together, where they preached subtly concealed hate about sin and the importance of the traditional family. I liked boys, so I knew I wasn’t a lesbian. But the only person I knew who was bisexual had been called a slut at school, and I didn’t want to be that. I didn’t even consider whether I had romantic feelings for her. It wasn’t an option. We never talked about it. We just moved on as if nothing had happened. Slowly, the time spent together became less focused on hiding behind closed doors and more focused on driving around town and going to diners. We sat in the pleather booths, doodling on placemats, eating the salads we thought teen girls should eat, and talked about boys, music, and school dances. The more time we spent talking about and doing what teenage girls are supposed to do, the more we drifted apart. Until there was nothing left to talk about.

I struggled a lot throughout high school and early adulthood with what I now understand to be disabilities, chronic illnesses, and the ableism that comes with them. I was always in and out of braces, crutches, and wheelchairs, recovering from something. Students and teachers regularly accused me of lying about my joint issues. When I seriously damaged my knee at the high school musical rehearsal, I had to yell before anyone would call an ambulance. The adult staff had simply let a few of the boys drag me off to the side of the stage so rehearsal could continue. Several adults and students told me to walk it off. I couldn’t walk for four more months, and I had to learn how to do everything from standing to driving all over again. During that time, a parent of another child asked me if my doctor knew I was in a wheelchair as if I had just decided it would be fun to try it out for a bit. As if someone would subject themselves to exclusion, bullying, harassment, and inaccessibility just for kicks. One of my teachers tried to have me expelled, and I had to spend several hours arguing with her and the guidance counselor. Not because I’d done anything wrong, but because the teacher decided I wasn’t making enough effort to thank the people who helped me get around the school in my wheelchair. I desperately relied on other forms of ableism to defend myself: I may need help to get around the school, but my GPA, SAT scores, and class rank are great. You wouldn’t want to expel someone like me, I’m a good disabled person.

The Diner had ramps, so I could find a way to sit at the table, often taking up an entire booth or a second chair to support an injured leg. I spent many meals there crying and venting to my mom or friends, trying to make sense of it all. Even though it was a public space where my bullies could be in the booth next to me, the frosted glass partitions, the plush padding of the familiar booths, and the cheesy perfection of mozzarella sticks made it seem like my secrets would be safe. It was a place where I could start to process the harms of ableism for the first time.

I still had a lot to learn.

My parents and uncle randomly showed up at my college dorm a few months later. I knew it was bad. They took me into an empty common room for privacy and told me my grandmother had passed away suddenly. I went home for the funeral and spent most of the time sitting alone by the bathrooms, practically screaming in tears. I refused to go into the room with the body. After the funeral, we went to The Diner with my extended family: cousins, aunts, uncles, and my great-grandmother. I was grateful for warm bread and made-from-scratch chicken noodle soup that felt like a warm hug. I didn’t know it would be the last time my family, who had been close for most of my life, would be in the same room. I wouldn’t see my cousins, aunt, or uncle again because of a feud that had nothing to do with me. I spent years after this feeling like I wasn’t good enough, like I must have somehow deserved to be cast aside and shunned.

By junior year of college, I had made a tight-knit group of college friends from all over the country. Some made fun of New Jersey, calling it an armpit or joking about Snookie and The Situation. At one point in my life, I would have enthusiastically agreed that I hated New Jersey. I had wanted nothing more than to leave. Instead, I was fiercely protective and started rattling off facts about how great New Jersey is.

Plus, we have the best diners.

These friends had only been to chain diners like the Silver Diner or Denny’s, so I insisted we go to a real Jersey Diner. They were shocked by the menu size. A few people kept asking how one restaurant could make all these different styles of food. Is it actually good? They marveled at the massive trays the staff carried past our table every few minutes, towering with pasta dishes, sandwiches, breakfast, and desserts. When they finally tasted the food, they were even more enthusiastic, surprised that it was as good as it smelled and looked. A victory for my newfound New Jersey pride.

Again, The Diner became a therapist’s office where I could vent and process — with the help of 24-hour breakfast — what I still didn’t understand as a disability. But it also made me angry. I wasn’t supposed to be in the same damn pleather booths anymore. I refused to register for disability services because decades of harmful societal messaging had told me that it was for “takers” and “lazy” people who didn’t want to work. I lost friends who started to say things like I wish I could stay home all day, and I’d rather be sick than at work.

But slowly, through fighting with doctors and insurance companies, the years of self-hate were beginning to unravel. I started questioning the ableist comments thrown at me, even while I was still incredibly ableist. I learned I was worth fighting for and speaking up for, and I stopped accepting the mean or dismissive things people said to me.

So one day, when I was at The Diner, my grade school bully came to say hello. Something changed.

He had been a year behind in elementary school, whereas I was a year ahead. So he was much bigger and stronger than I was. When he shouted across the playground that I was fat, an elephant, or an earthquake, the entire class laughed with him. But the supervising staff at recess said boys will be boys, and he grew ever more confident. One day, he pushed me to the ground and pushed my head into the brick wall. I remember trying to protect my head with my arms. I remember him yelling. Kids laughing. Teachers told him to knock it off, but that was it. There was no punishment for assaulting me. He simply went back to playing kickball, and I spent years pretending I was always in on the joke.

At the diner, my mom and I were sitting in the window in the rectangular pre-fab section near the door. I saw him come in with his mom and sit a few booths away from us. He came to say hello, acting very friendly, as if we were old friends catching up and breaking the bubble from the safety of my diner booth and chicken croquettes. I had had enough after many months of doctors dismissing me. I wasn’t willing to play along anymore. I told him about the hell he had caused me and the trauma he had inflicted, and I stopped apologizing for simply existing. He looked shocked and told me he had no memory of this and thought, if anything, that we were always friendly. I didn’t care. After years of bullying and having doctors, classmates, and grown adults question and doubt my disabilities, I finally decided I was worth speaking up.

For Thanksgiving, sometime before the pandemic, my partner came to New Jersey to spend the holiday with my loud, boisterous family at a dinner of about 20 people. I am out and proud and beginning to understand my identity as a queer disabled woman. When we arrived in New Jersey, my parents and I took my partner to The Diner. The waitress spoke in a thick Jersey accent and alternated between making low-key threats — I’m gonna kill ‘im if your food’s not out here in a minute — and calling everyone honey. She talked excitedly to my parents about how great it was for me to visit from D.C. We ate chicken noodle soup and Philly cheesesteaks while I worried about the next day: Even though New Jersey is a blue state, some of my family voted for Trump. But my extended family doesn’t just welcome my partner, they do it in a true New Jersey fashion: loudly and with a lot of oversharing. I feel at home and nostalgic for a version of my hometown that doesn’t really exist.

This is what it means to be from New Jersey. The roughness around the edges isn’t hidden away or sugar-coated. It’s fried and served with a handspun milkshake at a Diner in a town that will welcome you home with the same enthusiasm with which it taught you to hate yourself.

Diner Week is a 12-part series of essays curated and edited by Autostraddle Managing Editor Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya.

This was so good, thank you.

Thank you!

Katie!!! I learned so much about Jersey and about you. Thank you for sharing this 🍳❤️

Thank you <3

katie, i always learn so much from your beautiful work; i’m so grateful you share your talents, insight, and wisdom with us here 😊

Thank you Gina for this beautiful comment that brightened my day

This is so beautiful and prompted some lovely memories of my grandma, who was very proud to be from New Jersey. Thank you.

I am so glad <3

I just read this aloud to my New Jersey-born and raised girlfriend as a New Jersey born and raised femme. We are in alaska and squeeled and cried and are freaking tf out about this essay. You brought back so many memories that I didn’t even know I had, and your writing is absolutely gorgeous.

At one point, when I read your lines about defending New Jersey, my gf said: Didn’t you see Trenton lit up the Trenton Makes The World Takes sign in rainbow for pride? NEW JERSEY MAKES QUEER PEOPLE! THE WORLD TAKES US EVERYWHERE!

This is the representation I didn’t know I needed ;)

I visualized this as I read it and it made me so happy thank you

Katie, I adored this! From the Bruce Springsteen line, to practicing kissing girls, to see New Jersey and The Diner from your point of view, year after year, was such a treat. Thank you.

Thank you Carmen!

this is a fantastic love letter to the diner! feeling very seen by the comparison of a booth to a therapist’s office and the marathon catch-up sessions when you return to your hometown

Yes I’m glad that resonated with someone else

Thank you for this, Katie!!

Thanks Ro!

the bruce springsteen line gets me EVERY time, Katie!!!!

That makes my Jersey heart happy

I know it’s not the same diner – it can’t be, because a traffic calming project took it and the local dive bar/Chinese restaurant/indie band space long before COVID. But I know that diner because it is (was) my diner, too.

I grew up in a diner in Jersey, my grandma worked there and my mother worked there for over 40 years. I live on the west coast now, but it might as well be another planet. Thanks for capturing so very much about what being from Jersey is. Especially for those of us who are queer and chronically ill. (I had a teacher get me kicked out of honors English because she didn’t believe I really had Lyme disease…)

Ugh, I am so sorry that happened to you! Maybe it was my part of Jersey but almost all of us got Lyme at some

point from derping around in the woods.

Jess I relate to that so much, so frustrating

the Springsteen line is perfection, but it’s this line that really got me: “I feel at home and nostalgic for a version of my hometown that doesn’t really exist.” oof. you said a lot right there.

thank you Katie for sharing yourself so beautifully

This was such a beautiful read. Really captured the feeling of being queer in small-town Jersey. Also made me really miss my hometown diner

Every evening I go to the shops in New Jersey to buy pastries and enjoy drinks here. Due to its long-standing culinary tradition, the food here is delicious, especially the sandwich. These sandwiches have small, fresh slices of roast beef with thinly sliced onions. They snugly rest on soft, smooth potato rolls, and a layer of melted cheese adds to the enticing flavor.

This was great and so beautiful!! Thank you so much for sharing this.