*Background image in photos from Safiyah Ganpat via Unsplash

Many cultures celebrate the new year at different times, as a fresh start, or a new cycle. For me, the new year begins at 2 am on the streets of Port of Spain Trinidad, on Carnival Monday morning. This is J’ouvay — the Trinbagonian Creole word from the French jour ouvert — also known as the opening of the day. Many of our Creole words reflect our colonial ancestry, and although we were never a French colony, we had a large influx of immigration from the French Caribbean islands in the 1700s that left its mark on our language. But J’ouvay is more than a simple day-opening ceremony. It is a ritual. Revelers gather in the streets with buckets or bottles of mud, paint, or oil and cover each other, dancing to the sound of soca music or percussive bands. Paint, bodies, mud, and darkness wash my soul clean and I begin again. I am just one moving shape of many, covered, like a dark sea rolling through the streets.

Trinidad hasn’t held Carnival celebrations since 2020, for obvious reasons. But this February we are back on the road and there’s tension in the air as we prepare. There has been grief for the past two years, and there is a yearning to release it.

As I reflect on the rite that has bookmarked my life for so long, I wonder — where does my queerness fit in this story of our culture?

Although Trinbagonian Carnival has been a part of my life since childhood, there was no classroom teaching the impact of the queer community on Carnival culture. The older I got, the more I learned how meaningful that impact has been. Even in a sometimes hostile space, LGBTQ artists continued to create. I came out as queer as a teenager, and it would take me nearly another decade to come to terms with my gender fluidity, but there were always breadcrumbs. Gender rules that I couldn’t seem to follow or understand the need for, a fascination with people who were able to break free of those rules, and a small shivering want of breaking them myself. I look back at the parts of Carnival I was always drawn to, and I see it was my childhood self yearning for queer culture.

A historian at heart (just ask my super useful and definitely financially viable degree), I have long been fascinated with the history of Trinbagonian Carnival and how it informs the shape of our celebration today. As a young child — no older than 5 or 6 — I would be spellbound by the fire-breathing and “blood” spitting Blue Devils, the towering Moko Jumbies on 15ft stilts, and the loud and intimidating Midnight Robbers dressed all in black.

The beautiful displays of “pretty mas” (the term “mas” a synonym for Carnival which comes from the French Creole masquerades of the 1700s — and pretty meaning pretty) were nice sure, but there was something about the darker portrayals that took up space, and even challenged the crowds around them to sit with the discomfort of their presence, that spoke to me. They weren’t just there for everyone’s visual consumption. They were there to make you hear their story and acknowledge their existence whether you wanted to or not. They moved through the audience — demanding attention, invoking fear and excitement — and sometimes even requesting money before moving on. The antithesis of the cleaner and more commercialised parts of the festival that have become less and less accessible to the working class, who were the people that created this whole affair to begin with. It’s no surprise that this year’s new Carnival regulations trying to curb the rawness of these portrayals as “lewd and immoral behaviour” have been faced with an uproar — the project of gentrifying Trinbagonian Carnival continues.

Resisting the erasure of our roots and the commodifying of our culture is more intertwined with the struggle of our LGBTQ community than I realised. As we reject the colonialist ideals that have scarred our landscape, we reject the gender and sexual norms that have been foisted onto our ancestors. So these older art forms carry within them the memories of the ancestral roots of where Trinbagonian Carnival came from. The struggles of our people. Rebellion against subjugation. Laughing in the face of our oppressors. Making magic out of nothing. These traditions in many ways represented a freedom that could not be stolen away. The closer I looked, the more of my own queer culture and history I found.

Queerness exists in a paradoxical space in Carnival culture — ever-present but still hidden. Our most famous Carnival creations were born out of queer minds, and yet they were rarely truly able to loudly embrace their identity without a risk to their safety. Some of our oldest traditional characters are essentially drag — Baby Dolls and Dame Lorraines in flowing colourful gowns and bonnets, which are usually played and worn by men. Even though Trinidad and Tobago is still hesitant to embrace its vibrant queer community, our influence on the culture cannot be erased.

That’s not to say there aren’t queer artists making statements about their identity in Carnival. One of the iconic names in Trinbagonian Carnival artistry, Peter Minshall, designed a breathtaking Moko Jumbie ballerina for the 2016 Carnival King presentation, “The Dying Swan— Ras Nijinsky in Drag as Pavlova”. Our first Pride parade, hosted in 2018, played out like a Carnival event, people were dancing through the same streets that we would walk on Carnival Monday and Tuesday celebrations. While society is more willing to accept us in costume — on designated days— being out can still be dangerous. With Carnival approaching, I felt a need to express my own queerness and honour those that came before. I joined a traditional Carnival band called Tradition Reimagined, headed by local & vocal LGBTQ activist Cherisse Berkeley, niece of queer icon and winner of the most Carnival presentations EVER, Wayne Berkeley — and I knew exactly what I wanted to portray.

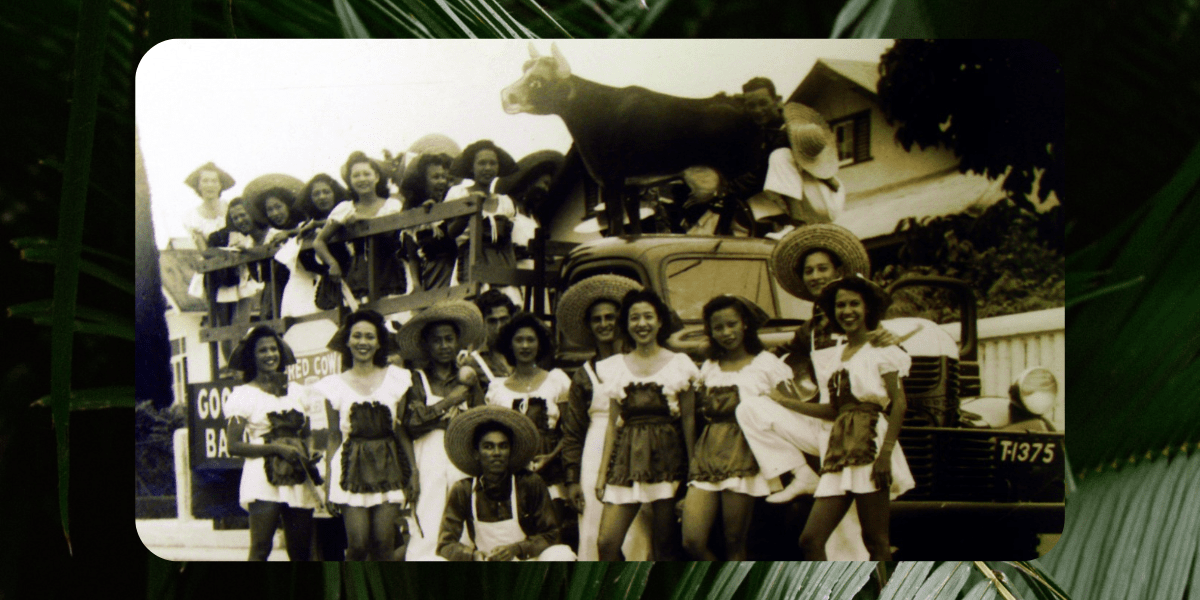

One of my treasured memories is a picture of my grandmother in her youth (around the 1950s), posing alongside a truck on the road. She is dressed in a fancy milkmaid costume for her band’s presentation that year. Of course, a milkmaid didn’t really suit my vibe, so I decided that instead — I would be The Cow. One of the oldest portrayals in our culture, Cow Mas, is rarely seen on the roads nowadays. With origins harkening back to African traditions brought here by the enslaved people, workers from the abattoir (another French linguistic remnant, meaning slaughterhouse) would dress in dried plantain leaves — with cow horns or full-headed cow masks —and charge through the streets embodying the animal form they were taking on. A usually male-dominated portrayal, the cow just felt right for me. Covered from head to toe with all identifying features obscured, I could be whoever I wanted to be.

There is gender euphoria in presenting as an otherworldly being, without the distractions of my body leaving people guessing about my identity. Paradoxically, behind a mask, I would be free to shed the metaphorical mask that had been fashioned for me by society. As I built it, slowly, with hanger wires, paper mache, and stolen banana leaves, it was like I was constructing myself. An act of pure self-love and self-creation.

This Carnival I will decide how I was seen.

I will not be afraid on the streets of my country.

I will take up space and reclaim my visage.

And for anyone who aims to get in my way — you know what they say about messing with the bull.

Photo Credit: Catherine Sforza

This was such a rich and beautifully written article. I’m a Barbadian and it’s not often you get to read and think on the queer behaviors and practices rooted in the culture of our region on such a mainstream outlet. There are so many elements that you wrote of that I can draw parallels with in the history of Crop Over and our similar yet slightly different carnival practices. I didn’t know I needed this type of representation until now. Your article made me feel seen. I look forward to reading more from you should you post more in the future. All de big ups and blessings fam 🙌🏾 🇹🇹🇧🇧

!!!!!

Europeans harden our faces, make them less spontaneously expressive, like an immobile mask. To lose face is to lose a mask, one’s sur-face. It is find yourself exposed, naked and vulnerable. The African alternative is to just be cool, which is to wear the mobile African mask of nonchalance and detachment. “What constitutes a mask?” asks John Berger. He answers: “A reputation with its exaggerations. A face with its expressions. A life-style with its acquisitions. A pair of eyes with their arranged signals. A body with its poses. Nearly everything personal presented to the world functions as mask. Social life demands this.” Here in Trinidad, however, masking is conscious and celebrated. The “mas” we play in our Carnival masquerade displays our dreams, whereas in daily life we “play ourselves”.

Thank you very much for writing and sharing this. The final costume you created is such a powerful visual image.

thanks for writing this

—

is the coming out article linked correctly?

This is so deeply specific and personal and also incredibly relatable. Particularly resonant for me was this section: “There is gender euphoria in presenting as an otherworldly being, without the distractions of my body leaving people guessing about my identity… I built it, slowly, with hanger wires, paper mache, and stolen banana leaves, it was like I was constructing myself. An act of pure self-love and self-creation.”

i love the blend of history + personal narrative in this!!! really great work

<3 <3 <3

thank you for sharing this here!!!!

<3 <3 <3

This was beautiful and fascinating! Thank you so much for sharing.

It reminds me I need to revisit Nalo Hopkinson’s fiction which is so often rooted in queer Black Caribbean traditions!

Hello! Excellent piece.

Would you be open to discussing your perspective on Love is Love.

That is the only Queer mainstream radio programme.

Sunday 26 Feb – 3-5 p.m. (TT) – please let me know.

[email protected]

“So these older art forms carry within them the memories of the ancestral roots…”

This year I learned that the origin of the steel pan was the outlawing of drums and any other instruments “not of European descent” in an effort to destroy our connection to our cultural heritage and prevent us from communicating in our traditional ways.

“I look back at the parts of Carnival I was always drawn to, and I see it was my childhood self yearning for queer culture.”

😭

“The closer I looked, the more of my own queer culture and history I found.”

Beautiful, sensitive, informative and powerful!!

Thank you for this work and to Autostraddle for making space for it 💕

As a dyke of Carribbean heritage it is so thrilling and healing to see our stories reflected here.

🇬🇾🇯🇲