Hiraeth. It’s a word with a complicated translation, more feeling than vocabulary. The kind of homesickness you feel for a home you cannot return to, that no longer exists, and, most likely, was never there in the first place. It’s longing and nostalgia for a different timeline, a different existence — an imagining of belonging that extends beyond what you already know. The word itself is Welsh in origin, but I’ve never seen a more succinct explanation of what it means to be a child of diaspora.

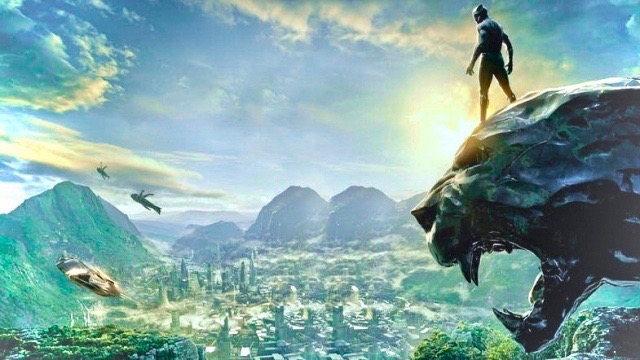

For those of us who are in the black diaspora, imagining and re-imaging our connection to Africa has been something of a cultural tradition spanning centuries. However, as director Ava DuVernay aptly put it, our reverent dreams are less often focused on place than they are using place to explore feeling, questioning “What if they didn’t come? And what if they didn’t take us? What would that have been?” These are the dreams of Wakanda, the underlying question that lead flocks of black audiences to track the development of Black Panther for years, creating grassroots hashtags from the first cast announcement, and becoming a driving force behind the film’s astonishing record breaking debut last weekend.

Wakanda, a small country roughly the size of New Jersey, hidden in Central-East Africa, has never been colonized. They’re the most technologically advanced and richest country in the world. They are unapologetically proud and steeped in their blackness. And sure, Wakanda is fictional, but it’s rooted in very real dreams of liberation. It’s built out of the same stardust that to lead slave rebellions in Haiti, and the founding of rebel maroon communities in the mountains of Jamaica. The stardust of the 1970s Black Panther Party proclaiming “Black Power” (the organization has no direct relation to the movie or the comic, though Black Panther director Ryan Coogler knowingly includes a poster of Black Panther Party founder Huey P. Newton in the film’s opening scene). It’s a daring, brave whisper; a hope, a glimmer that there are worlds for ourselves beyond the limitations of how white people see us.

To get the basics out of the way, Marvel’s Black Panther was originally conceived in 1966 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, before being passed down and reimagined by a variety of black writers and illustrators over the last 50 years. The titular hero, who’s given name is T’Challa, was first introduced to the Marvel Cinematic Universe in 2016’s Captain America: Civil War. In that movie T’Challa’s father, King T’Chaka is killed during an attack on the United Nations in Geneva. This year’s Black Panther takes place roughly one week later in that timeline. T’Challa has donned the Black Panther suit in order to protect his people.

For centuries, Wakanda has been the sole proprietor of vibranium, a natural alien element that produces a virtually indestructible metal (most famously known for being the material of Captain America’s shield). Wakanda’s rulers have wisely kept their homeland and its riches hidden from the world in order to protect themselves from the west. In their isolation, the nation has grown spectacularly powerful. T’Challa, charismatically and soulfully portrayed by Chadwick Boseman, wants to uphold the isolationism that has always kept his kingdom and its unvanquished people safe. Michael B. Jordan’s Erik Killmonger, the movie’s antagonist, raised in the United States and haunted by the horrors black people have endured on this continent, wants to use the Wakanda’s power in an arms race that he envisions will bring about global revolution.

(left to right) Danai Gurira as Okoye, Lupita Nyong’o as Nakia, and Florence Kasumba as Ayo

With no disrespect to the many detailed, deeply memorable performances given by the men of Black Panther’s cast, it’s the women of Wakanda who I couldn’t tear my eyes away from. Angela Basset stuns as Queen Ramonda, who provides guidance to her son as he grapples with his new responsibilities. Princess Shuri (Letitia Wright, already the instant fan favorite among the Autostraddle writers), is a teenager who’s engineering brilliance rivals only that of Tony Stark. She’s quick witted, bright, loving, and terribly brave. She spends the first half of the movie presiding over her tech lab, but when the time calls, she isn’t afraid to put her life on the line to defend her country.

Okoye (The Walking Dead’s Danai Gurira) walked away with my heart. She’s the head of the Dora Milaje, the royal family’s all-women bodyguard team, akin to our Secret Service. She’s tough and fearless and her hard femme aesthetic was not like anything I’ve seen on screen in this capacity. Her fight scenes left my mouth physically ajar more than once. Lupita Nyong’o stars as Nakia, T’Challa’s ex-girlfriend and a valued intelligence spy for Wakanda. If Marvel designed a James Bond-esque spin off featuring her character, I’d give them all of my money starting NOW.

(right) Letitia Wright as Princess Shuri

In Wakanda, there are no meek damsels in distress waiting to be saved. Nyong’o, Gurira, and Wright each spent weeks in combat training with the film’s stunt team. They’re equal partners in the fight to protect their home. They also have full fledged, varied, personalities. They are funny, or serious, wise, sneaky, nerdy, and geeky. Black Panther gives us more women, in more speaking parts, kicking more ass than any other Marvel film. More than the previous 17 Marvel films combined. In many ways, they are everything I could’ve hope for.

Multiple times throughout the movie, I could clearly imagine all the little girls who will now play “Black Panther” in their backyards or their living room. They will toss pillows in the air pretending they are shooting Shuri’s hand cannons, or climb trees like Nakia. They will corner their brothers with pretend spears like Okoye. They will make makeshift chemistry labs in their bedrooms and get dirty with grass stains on their knees. The thought alone, it left me teary.

Behind the scenes, there’s an even greater story to the “Women of Wakanda.” The textures, sights, and vibrant colors of the country were brought forth thanks to costume designer Ruth E. Carter, cinematographer Rachel Morrison, and production designer Hannah Beachler. Carter is twice Academy Award nominated for her work on Malcolm X and Amistad; she also worked on Ava DuVernay’s Selma. Rachel Morrison recently made history, becoming the first woman to be nominated for a Best Cinematography Oscar for her work on 2017’s Mudbound, directed by out director Dee Rees. With Black Panther Morrison also becomes the first woman to shoot a film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Hannah Beachler joined the Black Panther team after working on designs for Beyoncé’s Lemonade and last year’s Best Picture winner, Moonlight.

Working together, these women stitched together a Wakanda that pulled its aesthetics from across the continent. Their visual cues give a sense of rooted home and geography; creating a pan-African dreamscape that honors and uplifts, rather than demeans or belittles, real life African nations and tribes. Theirs is a breathtaking love letter to black beauty.

Angela Bassett as Queen Ramonda

If it feels like I’m spending too much careful attention on what essentially amounts to a blockbuster superhero flick, even if an exceptionally executed one, I’d like you to think about this: Comic book heroes are some of the most American, home grown, mythos that we have. They are the stories we tell each other, starting from the youngest age. They help us explain to children right from wrong. They reinforce the image of what we like most about ourselves, or the evils we want to dispel. These stories, they shape culture. And in the United States, those stories have largely been focused on blue-eyed Captains of America, Kansas-bred Kryptonian saviors, rich billionaire vigilantes, and the multi-generational space opera dramas of white fathers and their sons. They have focused on western values of individualism, and righteous manifest destiny.

Black Panther is about more than stunning CGI set pieces and slick fight choreography, though it has more than plenty of both. Set in an explicitly black context, it grapples with new questions of morality that uplift community over the individual, explores the roles we play in each other’s salvation. It wants to know, what are the obligations of those who have been granted freedom to those who remain without? Asking questions that hinge on the lived reality of systematic oppression is not something that Superman had to deal with, that’s for sure.

Many critics have pointed to Michael B. Jordan’s Killmonger when analyzing these themes of community responsibility and the black diaspora, but I don’t believe that the answer to this particular morality tale comes from his war mongering. Instead, I’d highlight Lupita Nyong’o as Nakia. Within the first 15 minutes of the movie, she confronts a team of Boko-Haram inspired Nigerian kidnappers. She tells T’Challa that she can never remain tied to Wakanda and its isolated wealth as long as so many others are in pain. Her desire for social change remains her character’s truest quality, right through the very end of the film. Wakanda may be fictional, but the worlds that both Killmonger and Nakia inhabit as black people outside of the nation’s borders are very real.

Using fantasy to imagine new solutions of black survival and social order is key to Afrofuturism, a word often associated with Black Panther. There’s a danger of thinking Afrofruturism simply mean “black people in a sci-fi.” To be truly considered Afrofutrist, a film or text must marry blackness, and mysticism or technology, within a social justice context. This tradition is part of what makes Black Panther stand out from its peers; its designed by its very nature to dig deeper than shiny spaceships and electronic communicators. In looking for answers of black liberation, Afrofuturism is often closely tied with black feminist art, and queer black feminist art in particular — ranging from the literature of Octavia Butler to the music of Janelle Monáe.

Maybe you already see the bridge I’m about to take here — I bring up Afrofuturism’s queer feminist ties, because, as much as I loved Black Panther, and my goodness I really loved this movie, I cannot in good faith write a glowing review and just ignore the deliberate queer erasure of their production.

Danai Gurira as Okoye and Florence Kasumba as Ayo

I don’t know how else to do this, so I am going to lay bare and be honest with you: I’m fighting my every instinct in talking about this publicly. As a black person walking around in this world, the last thing I want to do is bring negative attention onto what is such a massively important moment for black representation. But, as much as I want to turn a blind eye, I can’t minimize, ignore, or explain away these storytelling choices. We have to talk about this.

Let’s start at the beginning and walk through it together slowly: In 2016, Ta-Nehisi Coates began his tenure as head writer of Marvel’s Black Panther comic series, revamping the main character and Wakanda for new audiences. In Coates’ version of the series, two prominent members of the Dora Milaje, Ayo and Aneka, are in a romantic relationship. They run away together, founding a rebel feminist colony where they teach Wakandan women how to defend themselves against sexual predators. Later that same year, the Yona Harvey and out bisexual author Roxane Gay penned spin-off, entitled World of Wakanda, began its publishing cycle. The new series was designed as a prequel to Coate’s run, focusing on the Dora Milaje, particularly Ayo and Aneka’s love story.

Aneka and Ayo in “World of Wakanda” (2016)

In 2017, early clips of the Black Panther movie were screened for members of the press. In Vanity Fair, Joana Robinson gave a first hand account of a scene where:

We see Gurira’s Okoye and Kasumba’s Ayo swaying rhythmically back in formation with the rest of their team. Okoye eyes Ayo flirtatiously for a long time as the camera pans in on them. Eventually, she says, appreciatively and appraisingly, “You look good.” Ayo responds in kind. Okoye grins and replies, “I know.”

This scene was also independently reported at Vulture by Kyle Buchanan, who was in attendance for the screening.

It’s the smallest flirtation, barely a minute of screen time. Still, reports spread quickly that perhaps the Black Panther movie, building from the most recent run of the comics, was going to introduce Marvel’s first on screen queer romance — this time with Okoye filling Aneka’s role as Ayo’s potential lover. Within a few days, Marvel issued a correction that “the relationship between Danai Gurira’s Okoye and Florence Kasumba’s Ayo in Black Panther is not a romantic one and that specific love storyline from the comic World of Wakanda was not used as a source.” I’ll admit that as queer fan following the film’s production, I was pretty disappointed.

Still, there was a year to adjust expectations. This January, when early reviews of the completed film came about with reports that the small scene in question had been cut altogether, I didn’t think much of it.

Then Screen Crush interviewed Black Panther co-screen writer Joe Robert Cole about the incident, and I felt a creeping unease. When asked directly if there was an original intention of including World of Wakanda’s queer love story in the film, Cole said yes. While he couldn’t remember the specific flirtation mentioned in Vanity Fair a year prior, he could confirm that the filmmakers toyed with Ayo and Okoye in a variety of relationship dynamics, telling the reporter “We thought, ‘Well, maybe we’ll work it this way with an arc or work it that way with an arc.'”

If the film had just decided to drop its queer storyline, I could have looked the other way. I don’t believe that the romantic subplot was necessary for the film. I would have been perfectly happy to imagine Okoye and Ayo in a queer relationship on my own time. Unfortunately, they didn’t leave it alone. Instead, Okoye is saddled into a heterosexual relationship with W’Kabi, the head of Wakanda’s border patrol.

What bothered me most about this relationship, the reason I couldn’t let it aside, is not just that it’s a straight relationship put upon a character who was originally imagined as queer. It’s that the relationship in question was not necessary. W’Kabi and Okoye spend little time together on screen. They are never shown to be physically affectionate. Their romantic relationship is the basis for an important confrontation in the film’s third act battle, but I’d argue that this final scene would have been equally poignant if W’Kabi and Okoye had been best friends or siblings as opposed to lovers — and absolutely nothing else about their relationship would have changed. So, in a movie that was this clearly and carefully crafted, what exactly was the point of their relationship? What does their relationship really contribute to the narrative put forth by Black Panther other than to straightwash a queer coded character?

That’s the question that I couldn’t put down. Yet another small reminder of the ways that queer blackness means settling for conditional acceptance.

The very premise of Wakanda is based on imagining new black realities. Creating new legends, tales of heroics that aren’t predicated on whiteness. Stories of community and strength. Liberation and stardust.

Discussing the movie last weekend, one of the black writers at Autostraddle described Okoye and Ayo’s erasure as “feeling like someone kicked my knees from under me.” Another told me she felt disheartened and frustrated. A friend called it the “pebble in my shoe; I walk and walk, but I just can’t shake it out .”We all seemed to be waiting, wondering in hurried, hushed tones if we could even mention these bad feelings out loud. This was a time for black joy, for reclamation. Who are we to take up space and ask: Is there room in the promised land of Wakanda for us, too?

Tessa Thompson as Valkyrie

I’m not singling out Black Panther. This is the second time in less than a year that Marvel Studios had the opportunity to include the queer women from their comics, but made the production decision to straightwash them instead. Last fall, Tessa Thompson revealed that her Thor: Ragnarok character, Valkryie, shared a morning-after scene with a female lover that was cut from the final film. She clarified on Twitter, “Val is Bi in the comics & I was faithful to that in her depiction. But her sexuality isn’t explicitly addressed in Thor: Ragnarok.” Including Valkryie makes three potentially queer black women whose romantic screen time were cut from the Marvel Cinematic Universe with little-to-no fanfare.

When asked about her character, Ayo’s, queer erasure and lack of romantic attachment in Black Panther, actress Florence Kasumba told Vulture, “I’d love to [explore that], at some point. Not now, because it’s too soon.” Too soon. That’s something that black queer folks and black women have heard a lot in our lives. Change is incremental. Wait. First we need to make room for the broader success. Then, next time it can be your turn. Always, next time.

I want us to love on Black Panther, bravely and openly. But, we cannot forget the asterisk. We cannot forget that a significant achievement for black representation once again came on the back of forced black queer silence. It’s not the first time, and unfortunately it won’t be the last. We can embrace and celebrate Black Panther without losing track of that fact.

This weekend Black Panther made $242 million dollars domestically, and over $426 million worldwide. In all of cinema history, Black Panther’s debut only comes second to Star Wars: A Force Awakens. If we can dream of a black movie that can soar to these heights, then surely we can imagine a world where it can do so without sidelining its queer characters.

In Wakanda, they say: “Tell Them Who You Are.” Well, this is who I am.

Marvel better make room.

This is so beautiful. Everything you write comes from such a place of love. You are so open and excellent. <3

Thank you. That is really kind of you to say, this piece was super difficult for me to write. I really appreciate you going on the journey with me!

Absolutely wonderful review Carmen.

Thank you, Erin! I appreciate it.

I went to see the film and agree with you about everything.

SPOILERS?

I have one question though. First a caveat: I’m not black and I’m not from the US, so I might be missing something.

During the first half I was really happy with the plot, fighting that white supremacist South African and seeing lots and lots of Black people.

Then the theme switched to the conflict between two groups of Black people, the US Americans, and the Wakandans.

The plot seemed to say that the Africans are somehow at fault for not helping African Americans or that they even committed a crime against them. But in fact there is no Wakanda, because of white colonialism. And even if there were a Wakanda, the fate of African Americans would still not be their responsibility, it would still the responsibility of white colonialists.

So it rang a false note for me to me to even toy with such a plot.

But it seems to be meaningful and not racist for African American viewers, so I must assume that there is something that I just don’t get.

I’d really appreciate help, because I have been walking around with that question for a couple of days now.

“Killmonger is angry—not just at white supremacist oppressors or systemic racism, but also the Black Elite who left him behind. ”

https://shadowandact.com/erik-killmonger-forgotten-wakanda

This suggest that Wakanda doesn’t stand for a hypothetical country in Africa but symbolically for some groups of African Americans?

Do you agree with that interpretation?

I get where you’re coming from there, but at the same time, you can’t just say, Hey there’s this high tech country in Africa that hid from colonialism and they’ve got better tech than the west and not address the subject at all.

“And even if there were a Wakanda, the fate of African Americans would still not be their responsibility, it would still the responsibility of white colonialists.”

I’m not black, so maybe I don’t get a say here, but I think that if Wakanda was real, and spent the 17th and 18th centuries hiding out when they had far superior technology to the europeans and they watched everything happening around them and did nothing, they do get deserve some of the blame.

I want to be 100% clear here, I’m not talking about reality here, and not blaming Africans. I’m talking about a universe where there’s a Wakanda with sci-fi tech, some of it better than we have now, already in use during european colonialism, tech that could have easily tipped the balance.

I really hope for a reply from the author or some other Black people chiming in, but thank you for your reply.

Obviously *if* Wakanda existed like that and didn’t do anything, they would be to blame.

But that’s where my problem starts.

Who invented that Wakanda backstory? Is it the same as in the comics?

I somehow can’t imagine that a Black author would come up with that backstory without thinking about the implications for the history of slavery, i.e. laying a fictional blame on the Wakandans.

So are the film authors working with a comic canon invented by white authors?

Wikipedia says:

“Wakanda first appeared in Fantastic Four #52 (July 1966), and was created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby.[3]”

But I can’t find out where the canon that Wakanda self-isolated during slavery stems from.

I had similar problems with the backstory in Wonder Women btw. In that case I know that the more feminist comic backstory was distorted into what they show in the film.

I find that I agree quite a lot with TinTin’s first comment. I am black and not from the U.S., though I do live there now.

SPOILER

One of my critiques of the movie was that while it was set in Africa, this was very much a story of American black identity, and American politics. The conflict in the story is predicated on the idea that blacks all over the world are part of the same community, have similar values and by virtue of being black all help and support each other. Wakanda has failed to do this and is grappling with the morality of these decisions.

Being a black woman from another country, I find this American brand of politics particularly frustrating. For me and many black people all over the world, we are defined by our communities, our culture, our national identities, our tribes, far more then the color of our skin. These identities mean something, shape us from birth, in a way color may not.

And, any number of the above identities could include people who don’t share our color.

To me, the film goes to a country, where identity may or may not be shaped similarly, and asks them – why is your identity not based on the things Americans think it should be based on? Isn’t your color the most important thing to you? Don’t you see yourself as a part of a monolith with all other black peoples, regardless of how culturally diverse? Why have you not taken up the mantle of responsibility in relation to this monolith?

But the truth is there is no monolith.

Not seeing that is particularly ethnocentric.

I think Americans often times never have to see this – projection of your own culture and values onto other people often does not come with consequences when you are a superpower.

And yet, none of that removes the moral question of “if the people around you are being forced into slavery, what does it mean if you do nothing to help?” Do I think Wakanda had a moral obligation to help prevent slavery – probably. Do I think their color created this obligation? No.

There are any number of circumstances that can prevent this unity we think, in hindsight, should exist, when we look at slavery. E.g. 1 Malintzin is blamed for helping to lead Cortes across the Americas, even though she was a slave of the Aztecs herself. But in retrospect, b/c she was “brown” she should have had brown loyalty. 2. Naive school students often ask – why didn’t all the Native Americans come together and fight off the Europeans? This question is asked despite the fact that Native American groups all over the Americas were physically distant and culturally distinct, and may or may not have had social systems based on friendship or animosity in other groups.

We look at other people and identify them based on our current politics and then ask: “why on Earth would those people perform actions based on how they see themselves? That doesn’t make sense based on how *we* see them.”

What is the point of all this? I loved this movie for many reasons. But I feel the need to point that the politics it discusses, while important and revolutionary, are American politics. They are not about Africa, except for the American thought projection of what Africa could or *should* mean to black Americans. And American ideas of what blackness should mean to black people all around the world.

Thank you all for this insightful discussion.

Considering how long it’s been since the original comment, you might not see this reply, but I figured I’d put my two cents in.

I don’t think the film is laying any blame or fault on Wakanda at all. Wakanda isn’t responsible for the actions of the colonialists. Maybe they could have done something, but then again – it’s a fictional world. Any author could come along and give reasons why they didn’t help.

Assuming that they could have helped, but chose to stay hidden, I would think that the main reasons were fear and/or politics. The unknown is scary, so you can’t blame anyone for being afraid when some crazy dudes show up and start kidnapping people. There’s also the politics, which as everyone knows, gets in the way sometimes. Going to war is a pretty big issue, so I can imagine that it isn’t a simple decision for any government.

And my final point concerns responsibility. Wakanda isn’t responsible for the atrocities committed against others, but since this is a superhero story, they obviously discuss the responsibility of those with power to help those without. And considering this is a Marvel hero, created by Stan Lee, you have to think “With great power comes great responsibility.” In the context of the movie, Wakanda and the Black Panther have so much power to help people, but they mostly focus on their own issues (as superheros tend to do, at first). By the end of the movie, they learned the “error of their ways” and started helping people in need, wherever they lived. It’s kind of a simplistic analysis, but that’s a lesson that most Marvel heros have to learn. Almost all the major heroes in the MCU were too focused on their own problems (as most people are), before they started working towards the “greater good.”

Thank you Carmen, thank you thank you thank you for this & your other writing.

<3

“Yet another small reminder of the ways that queer blackness means settling for conditional acceptance.”

Whew that hit me!

I didn’t read the comics before the film (I do plan on doing so), but as I watched the film, and in the days after, I did keep asking myself why there weren’t any queer characters in the film.

Carmen, thank you for writing this.

Hit me up and let me know what you think about the comics!

The Ta-Nehisi ones are more brooding than the movie, but super interesting if you like political intrigue. World of Wakanda is dreamy, in a black feminist/ Afrofuturist way. Both series both were definite highlights of my reading materials last year.

And thanks for reading and being so supportive. It definitely means a lot.

1) “She spends the first half of the movie presiding over her tech lab, but when the time calls, she isn’t afraid to put her life on the line to defend her country.” I loved this but hadn’t explicitly thought about how unique it was until you put it like this. Most of the time, even when the tech expert is a woman (a la Felicity Smoak) they’re trapped in their lab the whole time. Yet another reason to be obsessed with Shuri.

And thanks for speaking so openly and lovingly about this movie. I think it can be a really good sign of how much you love something to want it to be better, yaknow?

Awesome review, thank you so much, Carmen! <3

Princes Shuri forever ever and ever and ever!

And, to your point, it’s also great that she’s a “Princess” who is more interested in STEM and combat than she is sitting around looking pretty (though she also is super pretty and very fashionable. Really, just the whole package.)

wonderful review

Thank you for this amazing, eloquent review. *SPOILER below*

There was a scene where (I think) Ayo was killed and Okoye’s reaction led me to believe that it wasn’t just a friend that died. Like it was more than a friendship. Very reminiscent of Tessa Thompson’s reaction when her “girlfriend” was killed in battle. And for that brief moment I forgot all about the supposed relationship between Okoye and the guy from Get Out.

After the movie was done I was talking with my wife and she mentioned how odd the lack of gay representation was. We chalked it up to homophobia in the black community. Like it’s so common to hear the sentiment that gayness is like a white disease that spread to us; that the homosexual condition is not indigenous to black people. I know there are queer Africans, but I’ve heard that line of thought before.

We were thinking of ways that they could have incorporated gay representation without it feeling trite or forced, or included just for the sake of including it. We thought that they could have made one of the leaders of the tribes gay without focusing too much on it. But then I felt that fit under the category of including just for the sake of including it. I didn’t know that the flirting scene with Okoye and Ayo was cut – that scene coupled with the killing would have been a great way to incorporate some representation in a way that’s subtle, natural, and meaningful. I agree 100% that they could have made the relationship between Okoye and the guy a platonic one and still achieve the desired effect.

So, SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

Ayo isn’t the person who [spoiler] in the final battle scene, that was another member of the Dora Milaje. We see Ayo later in the post-credits scene at the UN. She’s in the black dress on right (you can also see her in that scene if you scroll up a bit on this article. There’s a picture of Okoye in a black dress, Nakia in yellow dress, and Ayo at the end of the photo).

THAT SAID, yes absolutely! Your comment hit on a lot of my thoughts and feelings! There has to be a way to include these relationships so that they feel natural and meaningful as opposed to forced. I’m not asking for the whole world, just some authentic representation. Especially in a movie that supposed to be about revolutionary, futuristic blackness that is divorced from oppression and supremacy. You know?

Holy shit this was a gorgeous review <3

I can’t wait to see this tomorrow and then re-read your amazingly insightful review Carmen.

I am SO EXCITED for the costumes. To see a range of incredibly beautiful African and African-american aesthetics on screen. I come from a costume background and there is so little available on African fashion and costume history. Shout out of gratitude here to my best friend’s mom growing up, Amoafi Kwapong, who showed me the beauty of Ghanaian fashion, and the incredible designs being made in Kente cloth and other gorgeous fabrics. Nante yiye Amoafi – I haven’t forgotten <3 <3 <3.

Also, I could listen/read to this type of discussion about culture and representation all day. It so important!

The image that is coming to mind rn is “Culture saves lives” – work being done by First Nations people here in Vancouver to combat the problems of colonization.

It’s true. Culture saves lives.

There is no way in which wanting representation, including artistic, spiritual and symbolic aspects of culture is trivial. It is essential to our very being.

*It’s

This is amazing and I’m so glad you wrote about this. When Brittani Nichols had tweeted about it a few days before it premiered, my heart dropped and I was worried I wouldn’t be able to enjoy the movie at all. I love that movie, think it’s a masterpiece, but reading this allows me to hold both truths: that this movie is amazing/important/necessary and that black queerness shouldn’t be erased and it’s okay to be upset about that. Thank you for this.

Re: the women – the action scenes in which the Dora Milaje, and then later Nakia and Princess Shuri, take on Killmonger ALONE while Black Panther was elsewhere took my breath away. I don’t think I’ve ever scene in a super hero or action movie (other than the select few movies with only a female protagonist) in which female characters, even ones that are trained to fight and have badass characters, get a real shot at taking out the Big Bad Guy. I found it even more empowering than Wonder Woman. These women weren’t gods, just badass, trained, and armed humans working together to save the world.

I read about this somewhere else, but I misunderstood and thought the characters who had a relationship in the book weren’t in the film. I didn’t realize it was Ayo. I definitely agree that her relationship made no impact whatsoever. In the climactic scene where it really mattered I was like, “Oh, they’re together? I forgot.” Damn.

This was so well-written! Thank you for sharing it.

Beautiful. I want a Women of Wakanda spin-off like yesterday. And I don’t know if anyone has mentioned this, but Letitia Wright slays in the second season of the British television show “Humans.” My daughter and I did the speak at the same time thing when she first appeared on screen, whisper shouting, “Wasn’t she in Humans?” I’m sure everyone in the sold-out theater (third weekend after opening!) were pleased to get that bit of information.

along with 7 Wonders City Peshawar Nova City Peshawar is a premium housing community to live with style.