The Magician: Self-empowerment, action, manifestation

Have you prayed about it? That simple phrase immediately caused my shoulders to sag, my stomach to sink, my skin to prickle. After months of struggling, trying to convince myself to say the words I knew they wanted to hear, I had to confess to my youth pastor that I just didn’t feel called to the ministry. I was sure that it wasn’t what I wanted – nothing in me felt compelled to travel around the world, to beg strangers to convert, to speak of a Lord and Savior that seemed to demand more than I knew how to give. And yet that one innocuous question could instantly plant seeds of doubt. Have you prayed about it? Those words completely dismantled me every time I heard them, could leave me gasping for breath and wondering if I’d ever been certain about anything. In spite of my sureness, my confidence in the knowledge that I would be a horrible missionary and an even worse pastor’s wife, I still hesitated. I hated that phrase with every part of myself, hated the way those words made me distrust everything I felt and wanted and hoped for – but I hated the idea of going against God even more.

I’d always, always, prayed about it. Anything that I was considering, from the smallest decisions to the biggest choices, was wrapped in ceaseless, endless prayer. My days were defined by quiet, twisting monologues, constant whispered pleas to a God that seemed to be slipping through my fingers. Prayer was supposed to be both a confession and a submission, a chance to bring our most vulnerable selves to God and wait for comfort, assurance, answers. I never knew how I might receive a response, or if I’d get one at all, and it felt impossible to untangle the voice of God from the little whispers within me that longed for love, craved comfort, were desperate to feel accepted.

In the conservative, evangelical church that defined my childhood, I was taught to put my trust completely in a God that I couldn’t see, in a savior that lived hundreds of years before, and to prove my faith by submitting to commandments and restrictions much bigger than myself. I learned that there was profound goodness in admitting that I myself was too flawed and foolish, too inherently selfish, to make decisions that would glorify God. Daily, hourly, in every sermon and Bible study and prayer, I was called to release any power I carried and lay it at the foot of the cross, to give this immortal being the reins of control over my life and do whatever I was called to do. My purpose was to be humble, a vessel, an instrument of the God I served.

![]()

The trouble, of course, is that those callings are rarely as clear as we’d like them to be. God’s gentle guidance is often described in a way nearly identical to ideas of intuition – a gut feeling, a little voice inside of us, a guiding light that leads us to certain choices or decisions. And yet growing up, the nudges that I felt towards certain dreams, projects, ambitions, were rarely taken seriously by those around me. Something may have felt right to me, could resonate in my bones and thrum in my blood, but all I had to show for it was the intensity of my feelings. There was no way to prove where my decisions had come from, no way to make others hear and respect me, no way for my choices to seem valid to anyone else. And it was easy for that quiet internal voice to get drowned out by all the other, louder voices: the ones of my pastor and parents, leaders and mentors. As soon as that dreaded question came, I would be forced to reevaluate everything. Have you prayed about it?

Over the years, I got better at smothering that little voice, at ignoring her sobs and screams. Every time I tried to follow her directives, my own instincts, everyone around me seemed sure that God wanted something else for me, and after awhile I stopped fighting them. I am third, the popular phrase went: God first, neighbors second. My life and wants and needs and desires and fears and ambitions and hopes and dreams came third, last, eventually, never. After years of listening to every voice but my own, eventually it stopped feeling strange that God wasn’t whispering back the way he seemed to for everyone else, that he didn’t respond to my lonely, exhausted prayers. All I had was that sad, desperate little voice within me, and I’d been taught that she wasn’t to be trusted.

I had faith, for better or worse, which meant that I didn’t believe in magic. Even when we studied the miracles of Jesus, the powers that in fantasy books and fairytales are known as spells and witchcraft, we never called Christ a sorcerer. Instead we calmly accepted that God would always have power that we couldn’t have access to, could create and manifest in ways we never would. And it took me years to realize that in giving everything to God and the leaders who served him, in letting them be so big while I tried to take up the smallest space possible, I’d ended up with nothing for myself.

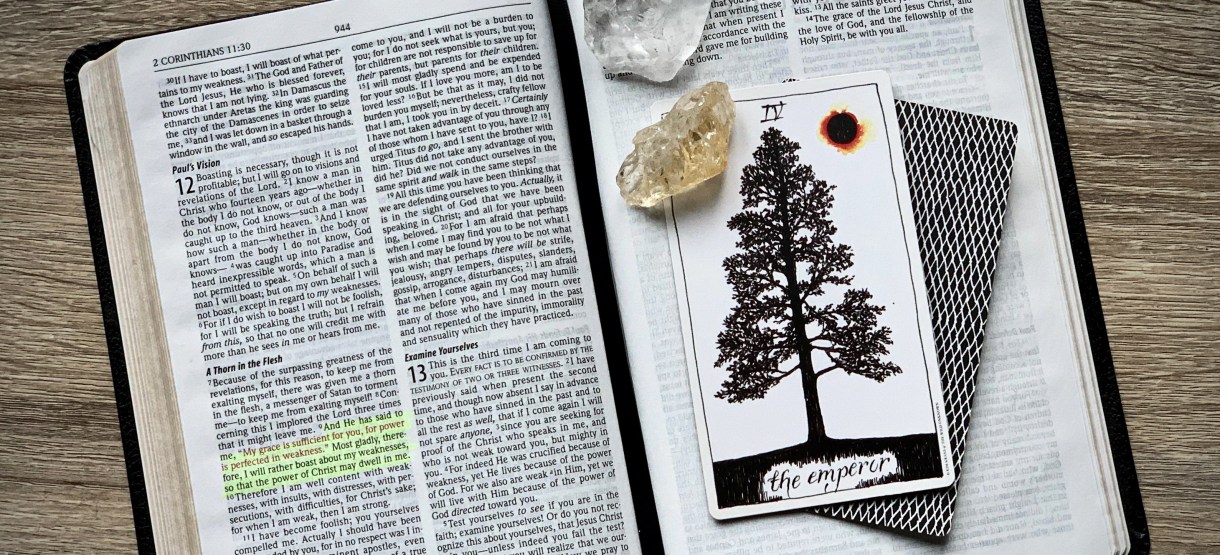

The Emperor: Protection, structure, discipline.

My childhood minister loved to preach about his favorite jazz musician. A trumpet player himself, my pastor found countless hours of pleasure and comfort in the brilliance of Wynton Marsalis, collecting records and imitating those powerful riffs to the best of his ability. The music comforted and healed him, providing a joyous burst of creativity and freedom during his troubled, often unsafe upbringing. And yet at some point in adulthood, my pastor decided that this love of music had become an idol, and he gave away every single one of those records and collectibles. It wasn’t that the music itself was sinful – no, instead it was that his pleasure in the music had become too great, and threatened to distract him from his ministry. It was worth the sacrifice, he would preach, to protect his relationship with God. Anything was worth giving up to keep that faith pure.

In the church, joy is jealously guarded. It’s not enough to be humble and submit to the will of God, to leave our lives in the hands of a higher power: I learned that we must also be willing to give up anything that provided too much pleasure, anything that could distract us from worship and service. If a hobby became too exciting, a relationship too intoxicating, a job too demanding, it was to be released, let go with joy and gratitude. Every time I heard my pastor share this story, I was reminded that God is to be our true comfort, the only lasting happiness, and anything else is merely a false idol, a worldly pleasure that’s to be avoided at all costs. Just as we’re to protect our physical selves from sexual sin or lust, we’re to protect our spiritual selves from distraction. Pleasure cannot be trusted.

Intuition isn’t a direct path to joy – few things are that simple. But teaching people that joy is only authentic when it’s linked to faith doesn’t only leave us floundering in the world, afraid to find happiness in literally anything – it also forces us to constantly judge ourselves, to worry about the morality of daily comforts or being safe or wanting more. We have to decide between the things that feel right and the things that others tell us are important, have to choose between what we want and what others want for us. How miserable do we have to be for our faith to be true? How much joy must we sacrifice to be pure? And when we’re told to deny our instincts for self-preservation, community, simple pleasures, how can we possibly trust ourselves to make decisions that are righteous in the eyes of an unknowable God?

The Hierophant: Seeking knowledge, a hunger for answers, a new ritual or practice.

I wish I could tell you that I left evangelicalism in a blaze of glory; that I stood up for myself and grasped my power in trembling hands; that I bravely, passionately told those power-hungry leaders to fuck right off. But my choice to leave the church wasn’t made in a moment of powerful independence and brilliant clarity, a deafening echo of indignation and anger. Rather it was a slow, gradual wandering, a quiet abandonment of the only life I’d ever known. I didn’t declare myself to anyone, didn’t put my foot down or write angry letters or formally renounce membership – instead I slowly slipped away, quietly fading into the dark. Church became just another thing I’d failed at, another place I didn’t fit in.

The anger came later, creeping in slowly, as the years passed and I couldn’t get comfortable anywhere. I shifted between jobs, drank too much, felt lost and frustrated no matter what I chose. I didn’t know how to live without the church, without the faith that had for so many years defined my decisions, but I knew I couldn’t survive within those harsh restraints anymore either. Even after coming out as bisexual, I still found myself aching for something more – longing for community, missing the weekly meetings and daily rituals, wanting to feel connected to something bigger than myself. I craved purpose, but had no idea where to find it.

![]()

Call it God, call it magic, call it intuition – I cannot explain the sudden, powerful obsession that compelled me to buy my first tarot deck. I’m a truly terrible sleeper, a diagnosed idiopathic insomniac, but in the summer of 2016 my sleep became frequented by strange images and unfamiliar figures. I started dreaming about archetypes I didn’t understand, which lead me to research cards I’d never seen before, wondering how to read when I’d never had a tarot reading myself. I didn’t know anyone that owned a set of cards, didn’t know how they worked, and yet for weeks I pored over images of decks online, read about their structure, craved the insights that they might provide. The little voice that I’d spent a lifetime ignoring was back in earnest, and this time she was unrelenting in her insistence that tarot was something I needed to learn. When I finally went to The Strand, flushed and trembling, to buy my very own deck, it felt like a personal, perfect little miracle.

But when I actually started working with my new cards, I quickly realized that I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. The directive that had seemed so clear before I got the deck home had abandoned me, and I fumbled my shuffles, stared blankly at the card images, flipped endlessly through my little book of descriptions. It had seemed so necessary to start reading tarot, to finally let my intuition guide me as I used this new tool, and yet I struggled to memorize meanings, felt clumsy and clueless every time I tried to do a reading for myself. Multiple times I gave up, putting the cards away in shame, taking days or weeks away from them and calling myself a failure – but every time I felt compelled to pull them out again, to keep struggling, to push on. I didn’t know what it all meant, wasn’t sure why I was so desperate to become a tarot reader. I only knew that I was obsessed with the idea, that I couldn’t shake the pull of the cards.

In retrospect, it makes sense that the day tarot clicked for me is the same day I started praying again.

Mother of Wands: Dynamic, protective, determined.

The pile of cardstock trembled in my hands like always that morning, the simple yet stark images from my Wild Unknown deck feeling particularly charged, begging me to understand. My card of the day, the mother of wands, was portrayed as a vivid red snake, coiled and protective, ready to strike at any moment – and my little book described her as vibrant, fierce, having overcome trauma to become someone courageous and tenacious. Brimming with fire and passion, grace and pride, with an inner core of deep, powerful magic, she was everything I wanted to be, everything that felt desperately out of reach. I’d never let myself be that bold, that sensual, that confident in my identity. I’d never loved myself that much, that I considered fighting for what I craved. I’d never really believed that I could be worth fighting for. Yet I saw another version of myself in that card, a fiery, brilliant leader who wasn’t afraid of her own desires, who held her power with pride and joy and eagerness. She was bursting with life, confident in her skin, so sure of her place and power and potential. She was amazing, and in the mother of wands I saw someone that I could become.

The card itself hadn’t changed, its meaning shifting or unlocking – but instead I stopped relying so heavily on the interpretations of others and let myself connect to the card from within, to find a meaning that made sense for me. I let the cards speak, without allowing anyone else to translate. And in that moment of clarity, it was pure instinct to bow my head in prayer, to whisper to a God that had felt out of reach for so many years, to cry out yet again for help, for wisdom, for something.

But this time, instead of repeating the familiar words of surrender, endlessly cycling through the sins I’d committed or the ways that I wasn’t worthy, I spoke to my god like a friend, a protector, a partner. I whispered about the life I wanted, the fire I’d been craving, the need to build a life that gave me pleasure and purpose. I let my intuition say everything she’d been aching to confess for so many years. And my god may not have spoken back with words, may not have answered in the ways that I had been taught to expect – but I could feel her listening, urging me forward, holding space for my pain. I felt heard, respected, like my words had value and my needs carried weight. I felt loved.

In my prayers and the mother of wands that day, I found my answer. And as I clung to my cards and felt things slowly, firmly clicking into place, I started to believe that I could have some power and magic of my own – that my god had been there all along, in those persistent little whispers. I’d just finally learned how to listen.

The High Priestess: Mystery, psychic wisdom, intuition, personal magic.

Paper and ink: that’s all the Bible is, all tarot cards are. Their weight, their magic, lies in how we use them, the ways that we understand them, the power that we assign to them. The Bible had never been mine, not in a way that felt as intensely personal as tarot does now – it had always been a way to control me, a tool for others to use in order to define who I was allowed to become. But within the cards, I discovered a path that’s all mine, gradually reclaiming a sense of mystery and identity and personal power that grows and thrives every single time I reach for one of my beloved decks. I find myself now on the other side of grace, having rejected one kind of faith and created another, one more honest and potent than any I’ve known before. My daily tarot readings, new and full moon rituals, writings and offerings and intuitive spells – they all remind me that I can make anything happen, that I don’t have to ask permission for the things I want and need. I’m allowed to discover new pleasures and practices, to trust what I know, to question what I don’t. I don’t worship the cards, don’t believe that they themselves have any power over me: the only magic they hold is what I give them, the magic that I keep discovering within myself.

I’ve found power in the cards, yes, but I’ve also discovered brilliance, agency, strength, truth, independence, intuition, joy. I’ve learned to trust myself in a way I never had before, to listen to that voice inside of me instead of smothering it. I’ve started writing in a way that feels authentic and powerful, and have had the privilege of seeing the impact my words and readings have on other people. Tarot isn’t just helping me find magic and power – now it allows me to help others. And older believers calling me a prayer warrior in my youth has never felt as good as friends and strangers thanking me for inviting them to choose a path forward, to find confidence, to reclaim some power for themselves.

![]()

I still pray. When I shuffle cards in the morning, when I feel flashes of fear or nerves or excitement, when I get ready for bed and reflect on my day, I whisper my hopes and dreams, the things I want to accomplish, the person I long to become. But my prayers are not the same cries for attention that they used to be – I’m not surrendering anything anymore, not crying out to an invisible creator in the hopes that they might hear me. Instead my prayers feel like declarations, setting intentions, taking back my power. I make spells, write confessions, create mantras. Prayers have become like magic – and deep down, isn’t it all rooted in the same power? We repeat the things we desire often enough, speak them into mirrors and whisper them in the dark and scribble them on paper, and they become part of us. We find power within ourselves, and wield it with confidence. We become our own kinds of magic.

My god may be the High Priestess now, instead of that faraway heavenly father – but I’ve learned that I can, and should, be a Priestess too.⚡

Edited by Rachel

![]()

“Prayers have become like magic – and deep down, isn’t it all rooted in the same power? We repeat the things we desire often enough, speak them into mirrors and whisper them in the dark and scribble them on paper, and they become part of us. We find power within ourselves, and wield it with confidence. We become our own kinds of magic.”

I love you.

i love you too, friend 🖤

“I’m allowed to discover new pleasures and practices, to trust what I know, to question what I don’t. I don’t worship the cards, don’t believe that they themselves have any power over me: the only magic they hold is what I give them, the magic that I keep discovering within myself.” I love this. The phrase “Have you prayed about this?” brings back so many feelings & I loved reading about how you turned it into something powerful. Thank you for sharing this with us!

I loved hearing how tarot cards and prior faith experiences integrated for you. God and faith are always so much bigger than the boxes we put them in. I learned something and now relate so much more to tarot than I ever did before.

Former Christian, current card slinger. Loved this. I think I need some cartomancy after dinner tonight.

hey this piece is intimate and a gift. thank you for sharing.

Damn, I love this piece. I identify with so much of it. You mention how the voice of god is often taught to us in a way that sounds like intuition and I identify with that so much. I think when I left the church, I locked away what was left of that intuition because I had always associated it with that. I’ve been using tarot cards to try to reclaim that voice as well and it is so hard, but necessary work.

Thank you for sharing this article. It gives voice to so much of the struggle we all feel upon leaving an institution that was essentially part of our culture. It reminds us that the hard work to find our voice is worth all that hard work.