It’s been a few years since the bicycle saved me; saved me from depression and healed me in moments of anxiety or when stunned by life’s darknesses and uncertainties. I use my bike as a means of transport in my hometown, I move freely wherever I want — although always with the caution of any woman who’s out at night in a country where there’s eight femicides every day, in a State that doesn’t offer protection, where harassment is a daily hassle.

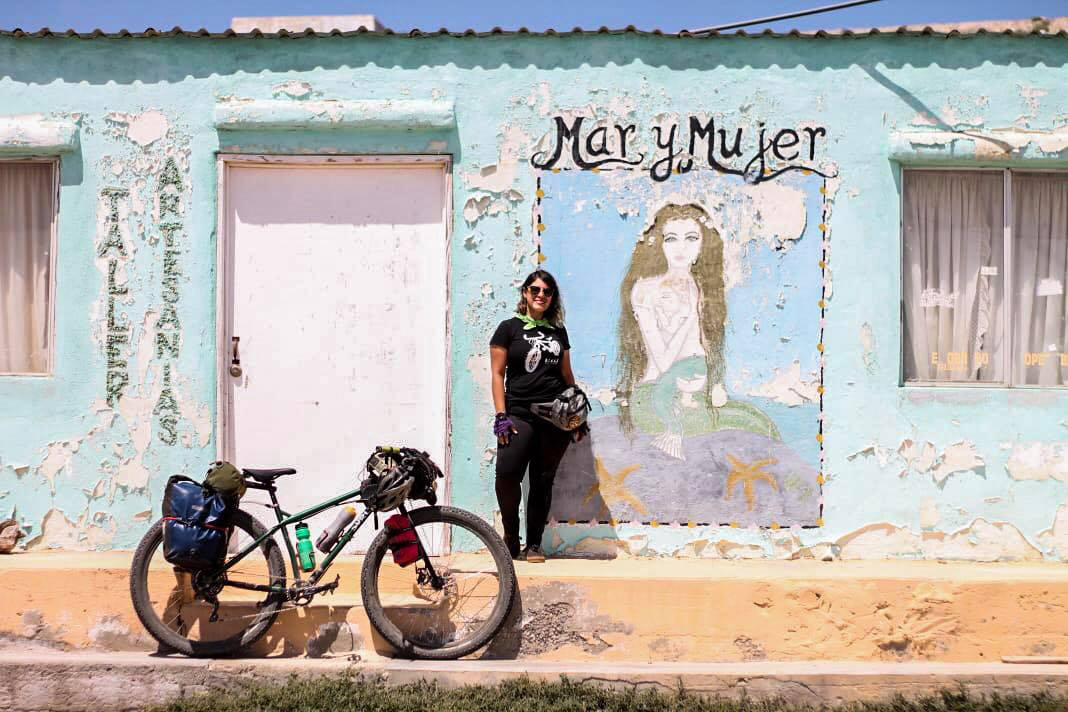

I was invited to use my bike as a tool for traveling and here I am, in the middle of a city kilometers away from home and after traveling more than 1000 km through a route so hard that it constantly made me doubt myself, my capacities and my ability to achieve my desires.

In Mexico it’s hard, as a woman, to travel by bike; it’s a country engaged in constant violence against women. It’s hard for us not to imagine being one of the women for which the rest of us claim justice. It’s hard for us not to imagine being the one who’s photograph is next to a Ni Una Menos (Not One [Woman] Less) banner. And this feeling is reinforced by how people ask, “Are you traveling alone?” “Aren’t you afraid?” “How do you dare to do it?” and by the expressions “What a relief to know you have company!” “How brave you are!”

What we want is not to be brave — but to be free. We know these comments and questions are not directed at men who travel by bike. Men in Mexico have liberties and privileges that the patriarchal system has granted to them.

Even so, Mexican women have dared to travel by bike and use it as a tool of autonomy.

Last year, I did just that for the first time, in what me and my partner named “Le Tour de Yaqui.” It was a trip through eight native towns in Sonora, in northern Mexico. The Yaquis or Yoemes (which means “people”) are one of the indigenous groups in the state who mix an attachment to Catholicism with their own beliefs and traditions.

Yoemes celebrate the Holy Week in a particular way, different to Catholic Yoris (the non-Yoeme). Tradition marks that during the Lent period, Jesus’ life is remembered through austerity and confrontation of individual and collective values by making sacred rituals and behavioral practices different from the usual, such as fasting or abstaining from meats and alcoholic beverages.

Some of these rituals represent the negative and positive forces of humanity and happen in different intensity. That’s what I saw when I lived among them on my bicycle. We did 190 km in five days, with the main objective to learn about their celebrations and traditions. My interest has always been the activity of women in their public affairs and their private life, and for the case of the Yaqui women in particular, they mainly take part in chants and prayers in their ceremonies, although they also participate in other ritual related matters.

To me, the trip represented a discovery of a new world that revealed itself to my eyes, my mind and my body; it cost a lot of physical effort, a constant interaction with my mind. I spent hours pedaling, reflecting and questioning everything. I thought about native women, their relationship with nature and culture and about myself, wanting to know everything about them. The Yaqui natives are famous for their resistance to Spanish colonization; for many years they fought to keep their land and at the end of the century before the Yaqui War took place and they were defeated by the Mexican government, subjecting them to slavery and ethnocide. Nowadays, the Yaquis remain in a constant struggle, defending their territory against extractivism and mega building projects.

I’ve realized that traveling by bike has opened up the possibility of knowing different historic and social contexts and aspects of my own life that I wouldn’t know otherwise. I’ve been traveling in Baja, California, for 60 days, following a route traced by a dissident woman and learning about very interesting people and places. The route is called Baja Divide and it’s mainly a dirt road route.

Before coming to this route I set myself a personal and feminist project: I wanted to know the women of Baja, and especially the natives’ way of life. I wondered “How do they live? What do they do? What are their social and economic activities? Are they different from Yaqui women? From Sonora women?”

Because of my formation as a sociologist and feminist, I’m interested in knowing the history and the social and economical context of the places I go to. Baja is full of natural and cultural history. When I arrived I came across the story of The Jatay Woman, from the Yumana nomadic civilization. Several researchers found a lump in the cranium of a woman caused by the time she’d spent underwater fishing for shells, an activity they’d previously thought was only done by men. This discovery opened up a new approach to the study of this civilization its non-traditional gender roles. The Woman of Jatay is also believed to have been a shaman, or somebody with an important position in the community.

There’s still blank spots in the research about the Yumana civilization, especially surrounding the vestiges this culture left in their rock paintings which represent diverse forms of social organization such as hunting, war, sacrifices, the sexual initiation of the youth, reproductive life and astronomical events like the equinoxes and their ancestral cosmovision in general. It’s wonderful to be in a place where events happened thousands of years ago that determined the life of the inhabitants of this state and to see high up in the rocks the memories of a disappeared civilization.

In the archeological site of Vallecitos in La Rumorosa, in northern Baja California, there’s rock paintings from the Yumana civilization and some of them represent a woman’s vulva. They’re painted in red, which I think might represent menstrual blood. In Baja California Sur there’s many stories of women with important political and religious positions, as they’re associated with the knowledge of wildlife. They were healers, sorceresses and shamans. The Yumana women are the ancestors of the women in Baja California, strong women who participated in the hunting and gathering activities just the same as men.

Along the route I met some women who share a double identity. They were in the tradition of a mother-woman but I could see strength in their voice and eyes. Some of them were artisans who worked with the local natural resources, crafting artistic objects such as lamps made of endemic trees or seashells. I also met Azucena; she approached me when I was on a city street after several very intense days of cycling in the mountains and the coast. She was waiting for a bus that would take her to do somebody’s laundry for some extra cash. With tears in her eyes she told me the man’s son whose laundry she was doing had been killed two years ago. He was shot 65 times at the age of 30 and had left behind a daughter, whom she wasn’t able to visit because of a disagreement with the mother. The grief for the early death of this son and not being able to visit his grave weighed on the woman. She wiped her tears and told me that the ranch where she lived was visited by many passing cyclists and she and her husband would give them water.

Her bus arrived and she left. After meeting Azucena, I thought that us women live the violence in different shapes. It’s structural and systemic. It touches our intimate life and always manifests in our social and cultural life.

So, when asked constantly whether I’m afraid of traveling by bike, the answer is yes, but the things you learn, the natural and cultural history, the social relationships that result because of it; the self-discovery of the body and mind of the resisting women, make it worth it. Traveling by bike is a political act and of resistance in Mexico and the world.🌲

edited by Heather Hogan.

Loved this piece! Thank you for sharing your story and stories of other women you’ve met.

I loved this peek into this culture!! Women are so strong regardless of culture. Your photos are stunning. Thank you so much!

I love the photos!

And I love hearing people’s bike stories.

And also your writing voice!

Fabulous pictures! What a ride!

This is an excellent piece with some great photos!