all archival images via OutHistory

When we’re faced with some of the harshest, most brutal attacks on our communities, we have the ability to look back at the resistance history of those who came before us to feel a sense of solidarity with those people and figure out how to respond in the present. Our most important tool for fighting the terrors of the present is understanding the strategies of the past. The trans and queer people who paved the way for us to live as openly as we do today employed a diversity of tactics against their oppressors. Their work ranged from legal action to direct action to violent action or some combination of all three and everything in between. And sometimes, they just refused to give in or back down. They just kept the party going until people left them alone.

Before I learned how to conduct archival research in college, I didn’t know the radical tradition of Just Saying “No” was as alive in my hometown of Ft. Lauderdale, Florida as it was anywhere else in the country. Florida then, as it is now, was both the best place and the most confounding and aggravating place on the planet. For all of the natural, cultural, and sexual freedom you can tap into here, there is and has always been a small army of fascist dictators who hope to take all of the beauty of this place and turn it into yet another golf course. I mean this metaphorically, of course, because what is a golf course except one of the ultimate zones of sterility in our society? What makes being here feel so good are the possibilities inhibition brings, the weirdness, and, most importantly of all, the queerness. Fascism and total political domination require subjugation and homogeneity — the more they try to chip away at differences in the public realm, the more reluctant people become to try to challenge them — but Florida’s long history of being a refuge for freaks has long confronted these attempts to turn the state into Golf Course, U.S.A.

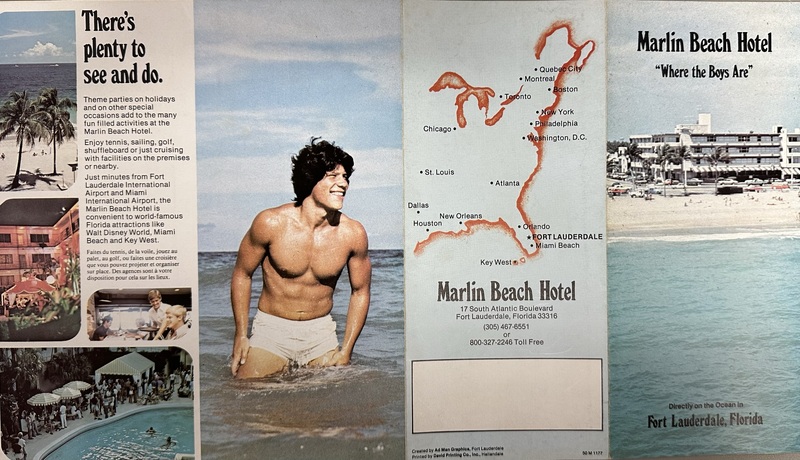

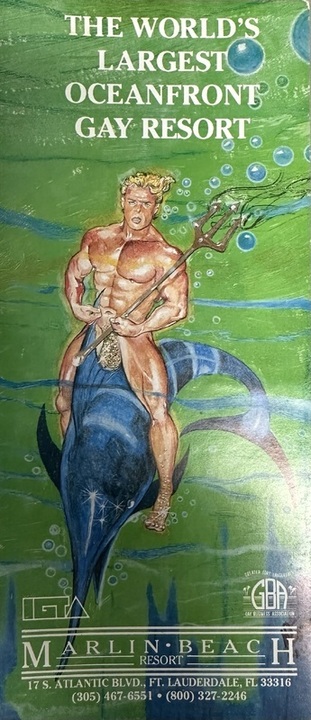

Ft. Lauderdale Beach was home to the first explicitly gay beach resort in U.S. history. When I tell others who grew up in South Florida that, they seldom believe me. I can’t fully blame them for that considering everything they see about the state’s politics in the media, but it doesn’t make the statement any less true. Although so much attention is paid to the queer history and tourist history of Miami just 30 minutes south of Ft. Lauderdale Beach in Broward County, the city should, technically, have its own chapter in the annals of queer resistance history. A variety of factors led to Ft. Lauderdale Beach’s surging popularity amongst queer people, gay men in particular: South Florida’s popularity among queer tourists surged as a result of it losing popularity with tourists in general. Broward County’s population was generally nonchalant toward the growing queer community, and meanwhile Miami’s queer establishments were getting raided by local authorities more and more. But what really sealed the deal for Ft. Lauderdale Beach’s queer reputation was the opening of The Marlin Beach Hotel at 17 South Atlantic Avenue in 1972.

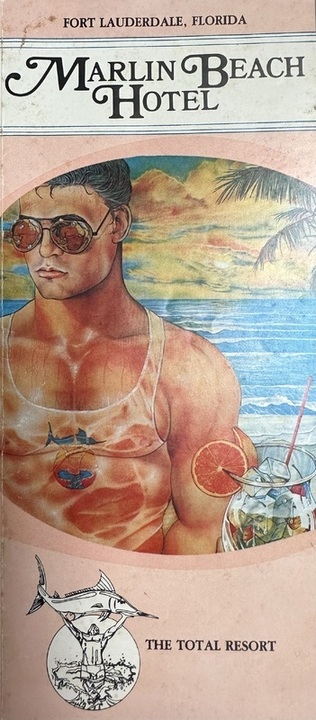

The hotel’s location already had quite a reputation as being a hotbed of “immoral” sexual activity throughout the 1960s due to being featured in the 1960 morality-film Where the Boys Are. After the film’s release and as family tourism in South Florida began declining, the hotel became the preferred spring break party spot for college students of all sexualities, but especially for gay men. By the late 1960s, the hotel was in need of complete renovation, but the previous owners decided enough was enough and put the place up for sale instead. It was quickly purchased by a group of gay investors and turned into what became the now-legendary Marlin Beach Hotel by openly gay marketing specialist and South Florida business giant John Castelli.

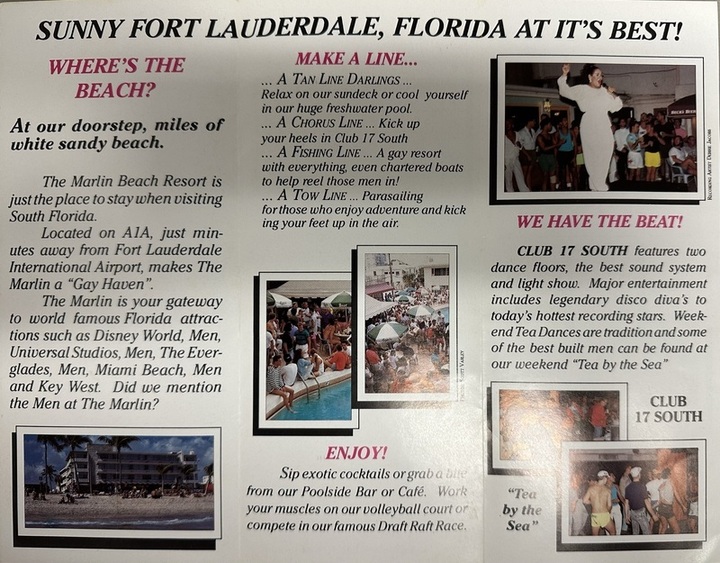

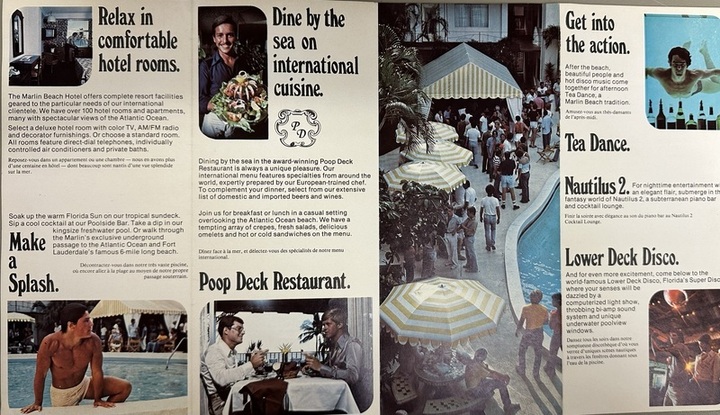

According to OutHistory, The Marlin Beach Hotel “was the jewel of the Fort Lauderdale beach’s hotels. Just across Highway AIA from the beach, it had over 105 rooms, a stage and dance area, two restaurants and bars, and an enclosed courtyard with a large pool. There was an underground tunnel that connected the hotel to the beach. The restaurant-bar downstairs had a large aquarium type window onto the pool, allowing diners to enjoy their meals while watching the water activities in the pool.” These features — along with its appearance in Where the Boys Are and its location where people could vacation almost all year long — made it an ideal spot for a gay resort, and Castelli and his team capitalized on that.

Under Castelli’s direction, a club called Club 17 South with two dance floors and a large stage for disco performers and drag queens was constructed inside the hotel and helped birth the hotel’s twice-a-weekend tea dance, “Tea by the Sea.” For more lowkey guests and patrons, a romantic, “subterranean” piano bar and cocktail lounge called the Nautilus 2 also opened inside the hotel. The new heart-shaped, king-size freshwater pool was flanked by a large sundeck and full-service poolside bar. If guests wanted to get away from the crowds at the hotel, they could walk the underground tunnel with their sweethearts and hook-ups out to the beach and spend the day there instead. Castelli turned The Marlin Beach Hotel into an absolute paradise for young gay men like himself and then marketed it openly that way through every available channel. Soon after The Marlin Beach Hotel’s opening, it became one of the biggest destinations for gay tourists and one of the best places to party for gay locals.

And with that came increased attention from people who didn’t think more and more gay presence in the city was a good thing.

In 1976, the Ft. Lauderdale Beach Advisory Board scapegoated The Marlin Beach Hotel and its patrons in a report about the conditions of the beach. They blamed the hotel for the appearance of more “street hustlers” along the beach’s drive, which caught the attention of the then-mayor of Ft. Lauderdale, E. Clay Shaw. A conservative Republican (of course), Shaw was quoted in a November 1976 article in The Fort Lauderdale News as saying “If a family from the Midwest comes to Fort Lauderdale and sees men making love on the beach, what will they think?… They’ll never come back.” An obviously absurd statement considering tourism in Ft. Lauderdale slowed way before the revitalized Marlin Beach Hotel even opened.

With that, Shaw began his little war against The Marlin Beach Hotel and all the gay men and queer people who found sanctuary in the resort. But The Marlin Beach Hotel’s owners and patrons as well as the greater queer community of Broward County weren’t going to let Shaw dismantle or stop the upward momentum of acceptance and collective care the community had been building for years.

In response the Shaw’s threat that the “City’s gays must go,” gay and queer people in Broward Country organized to use existing coalitions — the Fort Lauderdale congregation of the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) and a group of “gay professionals” called the Tuesday Night Group — and formed a new one: the Broward Coalition for Human Rights. Where the pastor and members of MCC did their part to speak out against the persecution of queer people in the Broward County community, the other groups took on more direct responsibilities. Members of the Tuesday Night Group “focused on quiet backstage networking with local officials and community leaders” and also used their broad connections to the closeted Ft. Lauderdale gay community to raise money and attention for the fight against Shaw and the municipal government.

The Broward Coalition for Human Rights challenged the mayor directly. They “openly organized and held a meeting attended by seventy-five people and open to the press” where they “called for a protest in front of the Mayor’s office the next day. Looking forward to the spring city elections, [the director of the coalition, Bob Kunst] said that the Broward County gay community, which he estimated numbering 100,000 (out of a population of 894,631), had sufficient political ‘clout to oust clearly defined opponents of gays.’” Not to give them credit, but even the local police mostly declined to get involved with the ongoing attacks on The Marlin Beach Hotel by Shaw and his municipal cronies. After a swath of harassment claims by members of the Tuesday Night Group against previous police action in that part of the beach, the city police took a neutral stance and bowed out of becoming yet another tool for Shaw to use against the hotel and its patrons.

Meanwhile, through the battle and Shaw’s attempts to make The Marlin Beach Hotel “go straight,” the hotel stayed open. Guests kept coming. “Tea by the Sea” raged on every weekend. And the gay men and queer people who claimed that part of the beach as their own continued to do so, regardless of how heated and messy the fight against Shaw got.

I find this part of the story the most fascinating and most important: When the community came under attack, people not only stuck up for each other legally and in the local media, they also kept showing up and doing what they always did. They continued spending money at the hotel and encouraged others to do the same. Even international gay and queer hotel patrons paid close attention to what was happening and supported the protests from afar. The people who loved The Marlin Beach Hotel, or who dreamed of going there someday because of the stories they’d heard, just said “No” and kept showing up, kept dancing, kept making out in the underground tunnel, and taking over the beach.

Their work was not necessarily revolutionary in a large-scale sense, but it certainly changed the trajectory of Ft. Lauderdale forever. After Shaw decided to cease his attempts at shutting the hotel down, more and more gay-owned and queer-friendly businesses began popping up all over the county. Even after the hotel’s business slowed down and after it eventually closed, gay tourism never really ended in South Florida, and Ft. Lauderdale even got its own “gay village,” Wilton Manors, from the remnants of the actions taken by gay rights and HIV/AIDS activists throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. They said “No” to every attempt to destroy the gay and queer community made from people on the outside, and then proceeded to say “No” through their actions, through their refusal to stop living openly and freely. Saying “No” made it possible for them to win against those destructive forces over and over again.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately as state-wide attacks in Florida and many other states —as well as the Federal attacks from the Trump administration —keep coming day after day. The reality is we can’t fight people who want us dead by insisting we deserve to be alive. So, what if we all, without asking for permission from anyone, just kept saying “No”? What if every time they passed a law, we not only ignored it but actively rejected succumbing to its mandates? What if we asked our friends and allies to do the same? We should be forming broad coalitions to protect one another, but that kind of organizing takes a lot of time and care that many people think they don’t (and in some cases actually don’t) have, so what if we just took this simple step first? We say “No” every time they insist on something that will potentially hurt us. We don’t look for flaws in their argument or try to fight back on rhetorical grounds. We just say “No” and keep it moving, keep showing up to the places and events that hold us, keep living how we want to live, keep making our way into spaces they’re trying to keep us out of.

We make the world our Marlin Beach Hotel and the spot on Ft. Lauderdale Beach it occupied, and we make “Tea by the Sea” happen every day by refusing to let them take anything else away from us. We say “No” — with our mouths, with our bodies, with our actions and reactions — and we let them figure the rest out. If we’re loud enough, it’ll be impossible for them to ever drown out the chorus.

Autostraddle’s Pride 2025 theme is DEVIANT BEHAVIOR.Read more, and be deviant!

Comments

Loved getting to read this history!

Love this! Drawing from queer history not only honours our ancestors but provides us with strategies in the present. And specifically, I’m interested in queer built heritage and how queerness is represented in architecture so glad to learn about this hotel!

i live in FTL with my very butch girlfriend. we are very happy here-gays everywhere. lesbians all over. lesbian parties every week in wilton manors

i love it here and never leaving-nobody can stop our party