As of late, LGBTQ rights advocates have challenged religious organizations for endorsing oppressive and discriminatory doctrine under the guise of spiritual guidance. These disagreements with the Church as an institution, while generally valid, particularly target historically Black churches and often reduce these congregations to a monolith of homophobia. Without a doubt, many historically Black churches have stood in opposition to marriage equality; but, it’s also important to recognize how historically Black churches fit into a larger context of LGBTQ rights and that the situation at hand may be more nuanced than it appears at first glance.

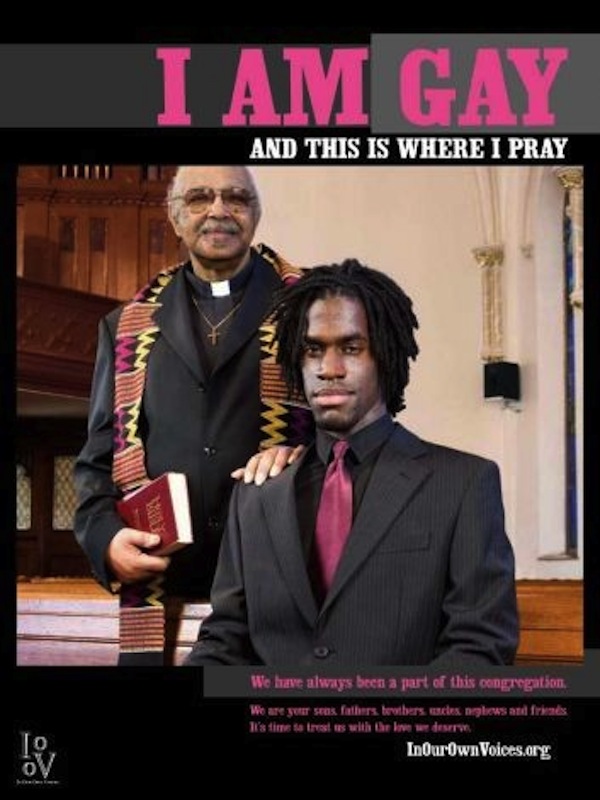

via Praise 102.1

When President Obama announced in May of 2012 that he supports same-sex marriage, his statement divided many members and leaders of historically Black churches. Although historically Black churches, like many other religious groups, have grappled with the question of LGBTQ acceptance, the fact that the nation’s first Black president — who once opposed same-sex marriage — aligned himself at least somewhat with LGBTQ individuals forced historically Black churches and congregations to break the silence surrounding the issue of queerness and faith.

Rev. Dr. Otis Moss III, the pastor of Trinity United Church of Chicago, spoke up only a few weeks after the President issued his support of same-sex marriage. Rev. Dr. Moss entered the conversation not only because he was President Obama’s former pastor, but also because he believed that even if the Black clergy who opposed same-sex marriage were unwilling to change their political position, they should at least be willing to further the dialogue between historically Black churches and LGBTQ communities. In his letter to the Black clergy and in a sermon, Rev. Dr. Moss encouraged religiously-inclined people to interrogate their beliefs and to make sure that their faith truly embraced a practice of love.

“Tell your brethren who are part of your ministerial coalition to ‘live their faith and not legislate their faith’ for the Constitution is designed to protect the rights of all. We must learn to be more than a one-issue community and seek the beloved community where we may not all agree, but we all recognize the fingerprint of the Divine upon all of humanity. There is no doubt people who are same-gender-loving who occupy prominent places in the body of Christ. For the clergy to hide from true dialogue with quick dismissive claims devised from poor biblical scholarship is as sinful as unthoughtful acceptance of a theological position. When we make biblical claims without sound interpretation we run the risk of adopting a doctrinal position of deep conviction but devoid of love. Deep faith may resonate in our position, but it is the ethic of love that forces us to prayerfully reexamine our position.”

Unfortunately, Rev. Dr. Moss’ support is hardly proof that once Obama endorsed same-sex marriage, Black religious folks decided that homosexuality is okay. In fact, many Black religious leaders voiced and continue to voice their deep disapproval for same-sex marriage and queerness. Former Illinois senator Rev. James Meeks targeted Black lawmakers’ territories by sending emergency robocalls condemning same-sex marriage to approximately 200,000 households. These Black religious leaders who stand in opposition to same-sex marriage often put enough pressure on lawmakers to stall or halt the repeals of same-sex marriage bans.

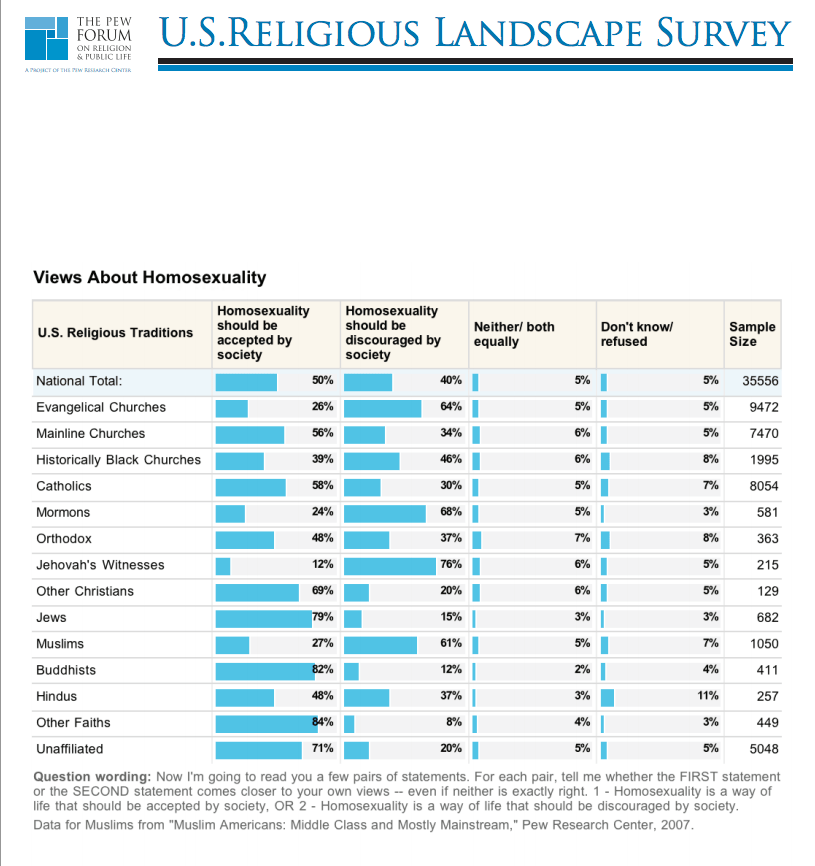

While historically Black churches have opposed same-sex marriages, using support of same-sex marriage as a measure of homophobia distorts the relationship between historically Black churches and queerness. In a study about views about homosexuality in U.S. religious traditions, the analysis found that 39% of historically Black churches think that homosexuality should be accepted by society, versus 46% that do not. These findings do suggest that historically Black churches are not eager to support queerness but when compared to other religious traditions, historically Black churches are far from the most homophobic. 64% of Evangelical Churches, 68% of Mormons, 76% of Jehovah’s Witnesses, and 61% of Muslims who participated in the survey think that homosexuality should be discouraged by society. If the reality of the situation is that historically Black churches are pretty split on the question of queerness, and it’s not like Black religious leaders are the largest population of Christians popping into other countries and preaching LGBTQ-hate (I see you right-wing Evangelicals), why are historically Black churches often deemed monolithic spaces of homophobia and the biggest proponents of anti-LGBTQ rhetoric?

This trend of almost unquestionably associating Black churches (and people) with homophobia stems from a lack of understanding or analysis of real Black communities. In the United States, whiteness is the norm; for that reason, when we think about white churches and their views on homosexuality, we can imagine all of the nuances that “white” can entail. It’s not hard to believe that not all white people or even all white churches are homophobic because our society teaches us that “whiteness” encompasses a lot of different categories. Furthermore, in LGBTQ spaces, we are overwhelmed with images of white people being queer, so it’s hard to think that all white people could be homophobic if clearly some queer white people exist. I believe that this phenomenon reveals why there are few research studies specifically devoted to homophobia in white communities or religious spaces. There’s an assumption in our society that we don’t need to study white behavior or culture because whiteness is the measure of what is socially or culturally “normal”. I mean, how many research studies have you seen that try to explain why white people are the way they are, period? It doesn’t matter that Westboro Baptist church is composed mostly of a white family, or that white evangelicals have spread hate for LGBTQ people in other countries; those people don’t represent all white people.

On the other hand, when our society invokes images or ideas of Black people, it’s as though there are only two ways to be Black: religious and intolerant of everything, or… not. Additionally, our society rarely speaks about Blackness in nuanced terms, and even throws around the phrase “the Black community” as if Black people form a homogenous collective. Therefore, when a group of Black people become associated with a quality — especially a negative quality — mainstream society imposes that quality on all Black people. Some church-going Black people are homophobic, so society portrays all Black people (especially if they are religious) as homophobic. And that, my friends, is how stereotypes are created.

It is important for those of us who care about the safety and well-being of LGBTQ communities to challenge groups and organizations that seek to oppress queer folks. However, if we treat historically Black churches as all anti-LGBTQ, we ignore our queer siblings who do find themselves in historically Black churches and also ignore the potential of alliances between LGBTQ communities and Black religious communities. For example, more than a few gay Black churches have sprouted up across the United States. Rev. Phyllis Pennese, an openly gay pastor, runs an African-American church with a predominantly LGBTQ congregation called Pillar of Love Fellowship. Pillar of Love, located in Chicago, was the 1,000th church to join the Open and Affirming (ONA) movement. The ONA movement consists of churches that belong to the United Church of Christ sect and are dedicated to providing a religious space for LGBTQ people. Rev. Pennese explains:

“Pillar of Love, like other ONA churches, is a community where LGBT individuals and families can be restored to wholeness. Our church motto is that ‘we have the courage to be all that God created.’ I do believe that because so many of us in the LGBT and black LGBT community have been abused and brutalized in the church, the only way we can heal and grow and walk confidently into what God has called us to be is to be showered with love.”

These gay Black churches are not limited to cities like Chicago. In Harlem, NY, a gay and a lesbian pastor merged their churches to form the Rivers at Rehoboth Church, a Black church with a mission of “radical inclusivity.” This inclusivity is not limited to only LGBTQ people but extends to any who have been marginalized.

The Rivers at Rehoboth choir and ministry

via The Spook Who Sat by the Door

As LGBTQ communities hold religious groups accountable for the wounds that they have inflicted on queer folks, we must be careful not to burn bridges that may be useful. When we simplify historically Black churches as only a monolith of homophobia, we alienate LGBTQ folks who may need the community and spiritual support that historically Black churches have provided them, we disregard Black churches that are creating new frameworks for LGBTQ inclusion, and we ignore the political potential of an alliance between LGBTQ and Black religious communities.

Historically Black churches have been political birthplaces for civil rights movements. The 1960s in particular saw the organization of protests, and political campaigns in Black houses of worship and among Black congregational members as well as religious leaders. Furthermore, in the Jim Crow era of U.S. history, historically Black churches had a less hostile and antagonistic relationship with LGBTQ people. In her book Salvation: Black People and Love, writer and social activist bell hooks suggests:

“Without idealizing the past, it is important for black people to remember that love was the foundation of the acceptance many gay individuals felt in the segregated communities they were raised in. While not everyone loved them or even accepted their lifestyle, there was enough affirmation present to sustain them. Since legalized racial segregation meant that black communities could not expel gay folks, those communities had to come to terms with the reality of gay people in their midst. Straight folks who had been taught by religious teachings to love everybody as oneself were compelled to create a practice of acceptance that was redemptive for both the heterosexual and the homosexual because it offered them an opportunity to, as it was common to say then, “live the faith.” … In some small segregated black communities the church was a safe house, providing both shelter and sanctuary for anyone looked upon as different or deviant, and that included gay believers.”

This church was built in 1823 as the Moravian church for African Americans

via Learn NC

Integration meant that historically Black churches no longer needed to exist as a sanctuary for people rejected from the mainstream white supremacist, patriarchal, heteronormative society. There were more spaces for Black LGBTQ folks to feel welcomed or to enter into, and perhaps this shift compromised the tradition of inclusivity that played such a big role in the structure of historically Black churches. Without returning to segregation, I still believe that historically Black churches can return to a model of inclusivity.

Bishop Yvette Flunder, founder of the gay Black church City of Refuge, argues that the reason why this divide between historically Black churches and queerness presents such a problem is that people working in Black churches get studied instead of being brought into conversations about faith and sexuality. Bishop Flunder insists in an interview with Religion Dispatches that “It’s just that folks are not talking to folks like me [who are people of faith and same-gender loving]. I have to make my way to folks to get them to hear.” In the interview, she explains that conversations about homosexuality and faith could really change the game. Using her relationship with her mother as an example, Bishop Flunder says that the more the two women talked theology and sexual orientation, the more their understanding of one another expanded until her mother eventually accepted that perhaps queerness and faith were not irreconcilable. Ultimately, her mother even went as far as to join Bishop Flunder’s gay Black church.

As a lesbian with ties to historically Black churches, I do not think it’s impossible to open up a real dialogue about queerness and spirituality. Historically Black churches, as well as other religious traditions, must be held accountable for the crimes that they have committed against queer people; however, I will not reduce historically Black churches to some exemplar of homophobia and hatred when the situation at hand has a more complicated story. Imagine a world where historically Black churches championed the rights of LGBTQ individuals. Such an alliance truly would be a force to reckon with, and I think that with time, dialogue and acceptance (not reluctant tolerance) we can move in that direction.

this is faTAStic

Thank you for the historical perspective and adding nuance to this conversation!

“Furthermore, in LGBTQ spaces, we are overwhelmed with images of white people being queer, so it’s hard to think that all white people could be homophobic if clearly some queer white people exist.”

Thank you so, so much for reporting this so thoroughly, especially this section. A hundred little lightbulbs just turned on in my head.

As a member of the Board of Directors of the United Church of Christ, thank you for this post! I just came from a board meeting last week, where so many of us were engaged in this type of dialogue. It is so easy to dismiss “black churches” or “rural churches” or “evangelical churches” as inherently anti-LGBT.

I am going to have to do some serious “sharing” of this article with members of my church, which will include passing printed copies around next Sunday for those not as technologically advanced.

“There’s an assumption in our society that we don’t need to study white behavior or culture because whiteness is the measure of what is socially or culturally “normal”. ”

This article was amazing, but this line in particular really nailed it for me as to why these conversations are so important. I’m going to be marking dozens of essays on “white privilege” next week, and I’ve been trying to give students concrete examples of what white privilege looks like and I want to give them this.

This is truly excellent. Thank you.

I also want to say how much I appreciate that Autostraddle is a place where religious/spiritual matters relevant to the community are discussed openly in a loving and judgment-free way. This is so not the case with many other very liberal blogs out there. Safe spaces for everyone should be safe spaces for everyone and you guys rock it hard.

I don’t have much time but I just really wanted to say this this article is awesome, wonderfully written, and that I’m showing it to a bunch of people. Seriously, bravo Helen.

Thank you for this, Helen! I am neither religious nor Black, but the trend of “queer culture” demonizing and homogenizing certain groups just because they aren’t white has to stop. We as a greater queer community hate when it is done to us by straight society, so why are we so quick to go there ourselves?

Thank you so much for this! As a queer black woman this whole article is so refreshing!

This is so great. Thank you! I constantly need to confront in myself the tendency to conflate historically black churches with homophobia. It’s stereotyping and influenced by racism and it’s just inaccurate. I’m a white Christian and I see this tendency in myself, other Christians, and really just everyone. It’s gotta stop.

I grew up in a black Baptist church in South Carolina. When my parents suspected I might be “that way,” they, being the deeply religious people that they are, sought help from none other than a fundamentalist pastor. I was sent to conversion therapy at 12, which was nothing more than mental and sometimes physical abuse. At 16, I was excommunicated from the church officially.

Now, by the time I was thrown out, I was already an agnostic. I would be a full blown atheist by 21. That didn’t stop the hurt and humiliation that came from being tossed out of the only community I had ever known just for being who I am, though.

I truly hope that these churches come around, if only to save others the pain of what I went through at their hands, all in the name of a god that most likely doesn’t even exist.

It will be a long time before I forgive those people for what they did completely, but I have made peace as best I can.

This is an excellent article. I was thinking about things in a shallow and racist way, and wasn’t even aware I was doing it. This article really made me think. Thank you so much for writing it.

The topic of LGBT for any Church has nothing to do with race so much as it does with Church doctrine, Natural law and God. The only point given for LGBT support is pure emotionalism. For instance, so called “Gay or same sex marriage”. The LGBT community can have a civil union and have all the protection and benefits afforded to anyone else.