“Homesickness is just a state of mind for me. I’m always missing someone or someplace or something, I’m always trying to get back to some imaginary somewhere. My life has been one long longing.”

– Elizabeth Wurtzel, “Prozac Nation”

It was the summer of my first broken heart, and the boy who broke it refused to let go of it — he didn’t want to take responsibility for it but didn’t want anybody else to have it, either. I told him, in light of our breakup, that I’d like to spend the summer in New York, but would return to Michigan in the fall for my final semester of college. He told me I had to stay in Michigan that summer, for him.

What can I say. I was 21 years old. I stayed.

I waited tables in my zany tie while periodically crawling under the bar to drink rum straight from the silver spout. I continued sleeping with my ex-boyfriend. I snorted just about anything you could crush with a credit card, ran five miles a day through a sweltering Midwestern July, sunbathed on my roof in the bikinis he’d chosen for me at Ron Jon during our trip to Cocoa Beach, and I read Elizabeth Wurtzel until my eyes burned.

“Prozac Nation” came out in 1994, the year my father died. I’d heard about it. I was a sad overeducated white girl and it was the mid-nineties: of course I’d heard about it. It felt like everybody was talking about it and about Reviving Ophelia (which came out that same year) and also about Prozac, a drug a series of doctors had suggested putting me on but I remained staunchly opposed to. I thought about reading Prozac Nation then, but I guess I was scared. I was already so sad. Instead I read Australian YA novels about the apocalypse.

Then it was the summer of 2003 and my heart was broken and so there I was on the roof on a bath towel reading Prozac Nation, by Elizabeth Wurtzel, who died today at the age of 52 from metastatic breast cancer. In her obituary, The New York Times notes that Prozac Nation “won praise for opening a dialogue about clinical depression and helped introduce an unsparing style of confessional writing that continues to endure.” It goes on to add that it “divided critics,” citing a Newsweek review that declared her “a Nation of one.” I had the same response, initially. I truly hadn’t expected it to be a confessional memoir about one very privileged woman’s life, I’d expected commentary on our generation, some type of comprehensive report. But I kept reading it anyhow, compelled not necessarily by her narrative so much as by the specific lines, here and there, that spoke to me directly, disarmingly, completely.

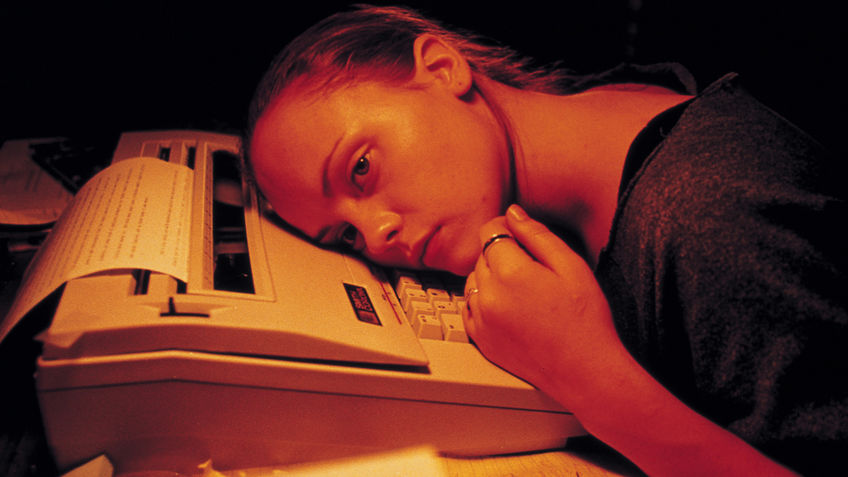

Christina Ricci as Elizabeth Wurtzel in the film adaptation of “Prozac Nation”

Elizabeth Wurtzel was born in New York City in 1967, and first began experiencing symptoms of depression around age ten. (She was later diagnosed with and medicated for bipolar disorder.) She was smart, too, and talented, and after graduating from Ramaz, a Jewish Modern Orthodox Day School on the Upper East Side, enrolled as an undergraduate at Harvard. She wrote for The Harvard Crimson. In 1986, she received the Rolling Stone College Journalism Award for a Crimson essay about Lou Reed. She went on to write about music for The New Yorker and The New York Times, writing that was loved and loathed in unequal measure (it was more often loathed). Although Prozac Nation received mostly critical acclaim, there was already a growing unease with the idea that a 27-year-old woman had anything to say at all. It was a New York Times bestseller, earning comparisons to Joan Didion and Sylvia Plath. A film adaptation, starring Christina Ricci and Jason Biggs, debuted in September 2001. It is a very bad film. Also, I own it on DVD.

Her memoir Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women, was published in 1998, and her memoir of drug addiction, More, Now Again, came out in 2001. In 2004, she enrolled in Yale Law School, and worked at a law firm from 2008-2012. In 2008, after his suicide, she wrote in New York Magazine about her relationship with David Foster Wallace, another famously depressed writer. In 2015, she wrote in The New York Times about carrying the BRCA mutation, a gene most commonly found in Ashkenazi Jewish women. She was undergoing chemotherapy at the time.

After that first book, everything else she published was usually panned or mocked — sometimes because it was bad, sometimes because she was a woman talking about her feelings and experiences as if they mattered. Even her 2015 marriage announcement in The New York Times noted, for no real reason, that Prozac Nation “makes Lena Dunham’s character in Girls seem like a well-adjusted Bo Peep” and was titled “Elizabeth Wurtzel Finds Somebody To Love Her.” A piece she published in New York Magazine a few years back was, I think I said at the time, one of the worst things they’d ever published, and had seemingly not been edited at all. There are plenty of bad things to say about Wurtzel — her politics and her prose.

Still.

I think what she articulated for me that nobody else had done quite so poignantly was that it was possible to be very smart, intellectually, while also feeling very stupid, emotionally. Or that, as she told a therapist in the middle of Prozac Nation, “how wonderful my life really was on paper, and how I would fall into these spells of depression for no reason, at the least likely times, times I ought to be happy.”

But it was More, Now Again that really got me in the gut that broken-hearted summer. It managed to pinpoint not only the spells of depression for no reason, but the shock of realizing how little was holding you together when you were okay, how short the distance was from “fine” to “death spiral.” One paragraph of that book left me dumbstruck with its accuracy (emphasis mine):

I’m one of those women who people call a dynamo, a powerhouse, that kind of thing. I practically raised myself; i’ve been working since I was in high school, supporting myself since college; I’m tough, I’m scrappy, I’ve got my own money; I don’t need nothing or no one. So whenever I get involved with some guy, he’s shocked to find out that I’m so human. I have such needs, a welter of needs — I’m like everyone else, only more so. I’ve been waiting for a break from holding it all together for so long that sometimes I just fall apart. And I always fall in love with these men who seem so sweet and angelic, gentle guys with softness and love. And then I’m shocked to find out that they, too, are human. They can be harsh, they can be mean, and they start to hate me for being such a sad girl, after all. We’re all hurt and disgusted by the bait-and-switch, like I never asked for this, where did that other person go?

And here’s what it comes down to: Most people would expect that my financial, artistic, and intellectual independence would be matched with an equal degree of emotional independence. But that’s not how it feels at all. All my good, solid ideals, all my feminist principles, all my hardy beliefs — and in the end, I just go to mush.

That’s why I do drugs: to fill the lacuna between who I am and who I want to be; between what I think and what I feel.

Because of Elizabeth Wurtzel, I wrote openly about having major depressive disorder on my livejournal (I know) for the first time, after trying desperately for years to keep it a secret, after believing desperately for years that it wasn’t my brain chemistry that needed fixing, it was my personality, and that I could fix it on my own, without therapy or medication. Because of Elizabeth Wurtzel, I went on anti-depressants for the first time, starting in January of 2004. I have been on them, on-and-off, ever since.

Over a year later I was undergoing a different type of self-discovery period, this time about my sexual orientation, and I found myself connecting to her words again. I didn’t know she had a piece in “Surface Tension: Love, Sex and Politics Between Lesbians and Straight Women” when I slid it off a crowded shelf in the basement of The Strand and dropped it into my basket, piled high with queer theory and coming out stories.

Reading it felt like coming full circle. “The (Fe)male Gaze” was about Wurtzel’s draw towards lesbian musicians broadly, but The Indigo Girls and Melissa Etheridge specifically, and about how she connected to their lesbian version of “the language created by all people on the margins.” “When I first heard [Like The Way I Do] in 1988, I had no idea that Melissa Etheridge was gay,” she wrote. “and I thought she gave voice to the obsessive, neurotic women who long to be this direct and obvious about the neediness we feel for the men in our lives.”

Before realizing I was queer, I’d been listening to queer music, although never in front of boys. Still, I lined my diary pages with quotes from the Indigo Girls and Ani DiFranco to express feelings I had about boyfriends and friendships, and felt, at Indigo Girls concerts, a sense of freedom not unlike what Elizabeth describes, although of course I never would’ve described it that way. Elizabeth writing about how the Indigo Girls “had to be the stuff of lesbianism”:

“It was more a total quality that emanated from that stage, a full-bodied and even excessive expression of unshackled emotionalism, of unfettered need and shameless want — this concert was a song cycle of liberation — that could only be the product of a world of, to paraphrase Hemingway, women without men. There was something about the Indigo Girls’ music, and particularly their live performances, that just had to be the result of divorcing one’s mind and one’s sexual concerns from the opinion — perhaps even the gaze — of men.”

These are generalizations, of course, and unfettered freedom to express neediness and obsession certainly has its drawbacks and dangerous manifestations. (Melissa Etheridge’s songs, for example, romanticize what is essentially stalking.) But she put her finger on something so resonant to me at that time, as I was in transition from a heterosexual college life into a queer grown-up life in New York. In the former, my friends and I felt constant pressure to be Cool Girls who didn’t care if a boy didn’t call when he said he would. We were assumed crazy from the jump simply for being girls, and had to work diligently away from that presupposition. When I wrote, I was painfully aware of the male gaze, and painfully motivated by internalized misogyny.

And I had been noticing, as I shifted away from that world — which is not to say the world of heterosexuality in total, but the specific world embodied by an mostly upper-middle-class social group of heterosexual undergraduates at a top-tier University that both Elizabeth and I had been a part of — that I was feeling freer in my writing. That I felt more free to be myself. I now realize this is mostly because “myself” is gay, not entirely because of any absolutisms or gender/sexuality essentialism about How Men Are and How Women Are. But at the time, it gave me the language I needed, which is all you can really ask of a writer.

I love a quote. I love a strong passage. I’ve almost memorized all the Elizabeth Wurtzel quotes I included here, even though I’d never cite her as one of my favorite writers, or her books as any of my favorite books. But the strength of those sentences, those quotes, and many others I have stored on desktop stickies and text edit documents and journal pages — I cannot imagine my life without them. Even that terrible essay in The Cut had some resonant moments, like her conviction that she “would not live another day feeling as awful as I did” but that her destiny as a writer required living another day.

“Depression is not a sudden disaster,” she wrote in Prozac Nation. “It is more like a cancer: At first its tumorous mass is not even noticeable to the careful eye, and then one day — wham! — there is a huge, deadly seven-pound lump lodged in your brain or your stomach or your shoulder blade, and this thing that your own body has produced is actually trying to kill you.”

When I saw that she had died, I assumed immediately that she had died by suicide, news that punched me in the gut. I was somehow morosely heartened and surprised to open the obituary and read that it had been cancer, not depression — but my gut didn’t slacken at all, only twist into a more understandable sadness. I wonder if, in the end, she was the most surprised and heartened of all.

Thank you for sharing this, Riese. I just loved it. I saw Elizabeth Wurtzel in the headline and the name felt familiar. I remembered I bought “Bitch” in high school shortly after I came out and was discovering more about feminism. But I’ve never finished it. I’ve tried multiple times and I’m not sure why I didn’t. Maybe I’ll take a look at it again.

Thanks Riese, for saying all the things ❤

Yes I feel this so much thank you.

Those quotes about the Indigo Girls and Melissa Etheridge are ones that I have thought of often over the years

Thanks for writing and sharing this piece, she meant a lot to me in my younger years and I hadn’t seen the news yet

Thank you for this. She meant a lot to me back in the day, too, and reading about how she impacted others is comforting.

One thing i would have wanted to ask Elizabeth Wurtzel about the paths she chose in life: what did you do that made your life better?

given her great ennergy and talent i wonder if she was lgbt.