Close your eyes and think of the last three queer nights you went to. Were they in a basement bar? Maybe some kind of dark, underground venue? Possibly a pop-up venue? Chances are the event you’re thinking of was one of the three things I predicted. If not, throw those nights down in the comments because I wanna be there after lockdown.

What I didn’t predict back in 2010 and on a fairly new fundraising platform called Kickstarter, was that when I threw down a couple bucks to back a lesbian documentary about a strip club in LA called Shakedown, it would still feel unapologetically ground breaking a decade later. Leilah Weinraub, a regular patron of the club in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, brings us sexy and liberating joy in a 70-minute showcase, also named Shakedown.

In the early 2000’s (I’m talking 2002, 2003 when J Lo released her Glo perfume) and long before social media and smartphones cast an abundance of events, Shakedown advertised on DIY flyers and word of mouth. Each event, held at LA’s Club New York, filled up with a majority Black lesbian clientele. Shakedown, the documentary, was shot at a time when what happens in the club stays in the club, sex work was a less acceptable form of work than it is now and the concept of privacy (because smartphones were not so popular) was a serious matter. It’s because of these small details that I feel lucky we are able to watch the film right now for free wherever we are.

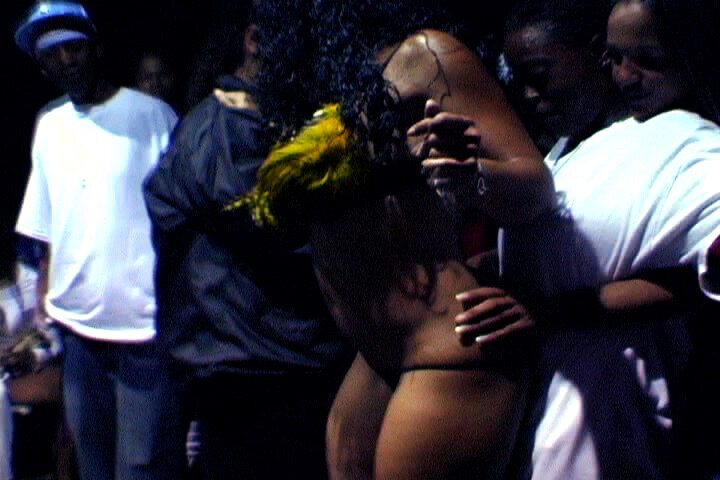

This footage may never have made its way off the reels, onto hard drives and .mp4 files without the support of community funding. Shakedown came to fruition through the mutual aid of 694 backers pledging $29,525 to support Weinraub in finishing the film. Whilst we were not there in the editing room, Leilah’s documentary certainly helps us feel like we were at the club. It’s dark and the music is loud. Shakedown’s stage is the customers’ dance floor and Black women of all shapes, sizes, identities, labels exist freely and we get to see the full figures of these women and the space full of sheer and queer joy, desire, freedom.

Exotic entertainers, Egypt, Ms Mahogany and Jazmyne share stories with Weinraub in cutaway interviews. We learn that Ronnie-Ron, Mahogany’s “gay lesbian son” and an ex-Mormon, started Shakedown because Mahogany suggested they did. We’re told Mahogany was also called “Mother” by other dances because she looked after so many of them, giving them tips on technique and confidence.

Inside my home, with our current sense of uncertainty, there’s an element of grief watching in quarantine, thinking about the ways Black queer burlesque, strip and drag nights have been part of my coming out into the Black queer scene. We see scenes of one dancer strapping a hot pink dildo and grinding into a customer lying on the floor. At first it seems wild, but to have a space like that where queer sexuality and sex acts are normalized and displayed so openly is liberating. To see both the client and the dancer enjoying this moment, as dollar bills fly in the air, is sexy. This is followed by another dancer striping down to nothing, grinding into customers. Jazmyne finds a customer and begins to lift their bra; the customer does this to reveal her breasts – Jazmyne puts the customers nipple in her mouth. Backstage we see banter between dancers joking “they got a dollar for me?”

Viewing Shakedown through an almost all-access lens, reminded me spaces like this are more than just strip clubs; they’re community. This sense of community is its most beautiful when we hear that Ronnie-Ron shut the club early to visit new parents Tara and Shan and their newborn baby in the hospital. This sense of community amongst dancers, Ronnie-Ron and customers feels joyous and liberating. As we approach 54 minutes into the documentary, the ways our spaces can be so quickly taken away comes to light.

Jazmyne, is half way through her entertainer set, when the music stops and the lights come on to reveal three police officers handcuffing her wearing only her underwear. We see other dancers and customers trying to put clothes on her whilst she remains cuffed. ”You needed to wait,” Weinraub is shouting at the cops. Jazmyne is ticketed for soliciting. Our spaces are policed by the very institutions we are told are there to protect us. What was once safe no longer feels that way even as viewers — we’re brought so close to the action through Weinraub’s filming style.

In the next scene, we see the way Egypt shows you how she wants you to interact with her — she’s in charge of the space and the performance. Yet, Egypt’s performance is cut short. The music stops and Ronnie-Ron announces over a PA that the cops are there again. In a follow-up scene it appears Weinraub is detained by the cops.

Even when we create spaces for ourselves, they are at risk of being taken away by institutions. In Shakedown, we see the policing of queer spaces as the police enter the premises several times, handcuff entertainers who are not fully dressed and carry out checks that the event is legal. The constant police interference which led to the shutting down of Shakedown feels really close to the Pussy Palace Toronto raids (around the same time), in which two undercover female police officers attended and investigated the event prior to the raid. Five male police officers then entered and searched the club, including private rooms. It was a damn mess.

In LA, Black people live in a state of being policed — at least it’s seemed that way to me, watching dash cam footage of Black men during traffic stops, the Rodney King riots ten years prior to the filming of Shakedown, and The California State Prison System. The policing of Black bodies, particularly queer and trans bodies, and even more so women and femmes who often get left out of the narrative (Breonna Taylor’s murderers are still free). I wrote recently about the policing of Black trans spaces, which highlighted anti-Blackness, transphobia and homophobia showing up in instances. In this moment of heightened awareness of police brutality against Black bodies, it’s worrying to watch the acts of violence we might choose to otherwise minimize or overlook as our spaces and bodies are being policed by institutions. Black queer communities often have to build our own families and places to be free; when we find that joy and pleasure and community it is then policed or surveilled.

If it’s not police shutting down our safe, liberating, community spaces, it’s the places we want to hold them that can become difficult to access or hire purely because we are Black, queer or running an event that does not cater to white men. When the police entered Shakedown, someone says, “There’s gonna be no peace in this place.” In light of these events, Ronnie-Ron decides to have one last Shakedown before ending the night for good. “We’re gonna go higher; we’re gonna take it to another level.”

There is yet to be space that mirrors the feel Shakedown successfully invited viewers to experience, but there are certainly individuals trying to carve spaces for Black queer communities. In London, we’ve seen a resurgence of Queer and POC spaces, like Shakedown, pop up every few months, publicized through social media, aiming to cultivate similar joy. Even 15 years after its closure pushed by the LAPD, Shakedown reminds me of a rare, yet almost vital subculture that operates in the shadows of a double edged sword. In order to remain safe, we must stay small, intimate and underground. On the other hand, to continue to thrive financially, gain momentum and share our community, we have to make ourselves known and run the risk of being shut down by a system that continues to violently police us.

From start to finish, Shakedown shows examples of the power of community. We begin with Ronnie-Ron building this space, women supporting one another as entertainers and then us, the viewers, supporting the film to be made. It’s community that’s key here. Even after LAPD’s shut down Shakedown shutting down in 2004 — we came back and supported Weinraub to finish this film and carve out a piece of history.

Shakedown is available to view for free.

I watched this at the start of Corona and was mesmerised! Nothing else like it.

same!

Felt mesmerized too! A really intimate documentary.

Thanks for this, Bailey. I’d made a promise to myself to watch this documentary after hearing about it on the Nancy podcast and never got around to it. I’m especially interested to watch it now that P-Valley‘s out in the world and makes for a really interesting comparison (Ronnie-Ron and Uncle Clifford seem like similar characters).

i really enjoyed that episode of Nancy! Great article

I had not heard of P-Valley until now, thank you Natalie!

Thank you. I wish we can get more spaces like this back.

Fingers crossed!

I watched this documentary a couple of months ago. Brought back memories of going to Shakedown in the aughts…(prayer hands there were no camera phones). I miss spaces like this!

<3 thank you for reading – what an experience it must have been to be at Shakedown!